Library of Congress

Library of CongressIn this painting by Thure de Thulstrup, Union generals Ulysses S. Grant (light overcoat, holding binoculars) and George H. Thomas observe the Battle of Missionary Ridge from atop Orchard Knob during the Chattanooga Campaign.

Twice in 1863, as part of the Army of the Potomac, the 154th New York Volunteer Infantry was badly mauled in battle. At Chancellorsville in May, it suffered 240 casualties out of 590 men present, a loss rate of 40%—the fourth-highest casualty count among all regiments. Two months later, at Gettysburg in July, the 154th took 265 men into battle and 207 of them became casualties, a 77% loss rate—one of the highest incurred by any regiment in any battle. In September, part of the army’s XI Corps, including the 154th New York, and its XII Corps were transferred by rail to the Civil War’s western theater. The move coincided with the first anniversary of the regiment’s muster into service. The weeklong trip was one of the great logistical feats of the conflict, wending from Washington, D.C., through Maryland, West Virginia, Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky, and Tennessee to terminate at Bridgeport, Alabama. The battle-hardened veterans enjoyed their reception from patriotic Unionists along the way, particularly in Ohio and Indiana.

The 154th disembarked at Bridgeport on October 2, numbering 161 officers and enlisted men. The next day a group of exchanged Chancellorsville prisoners arrived, bringing the regiment’s strength to about 250. Everyone knew why troops of the XI and XII Corps, under the overall command of Major General Joseph Hooker, had been sent west from the Army of the Potomac. About 25 miles to the east of Bridgeport as the crow flies, the Army of the Cumberland was besieged by Confederates in Chattanooga, Tennessee, having been driven there after the Union defeat at Chickamauga.

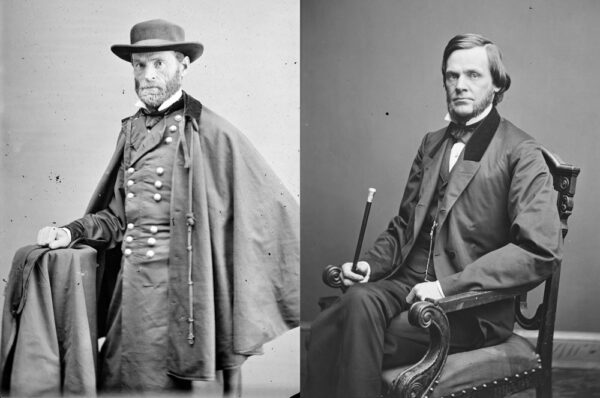

Hooker’s eastern troops were not the only reinforcements hurrying to relieve their comrades. Coming from the west were troops of the Army of the Tennessee under Major General William T. Sherman. Two weeks after the 154th New York arrived at Bridgeport, Major General Ulysses S. Grant was placed in command of the newly created Military Division of the Mississippi, overseeing Sherman’s army, the Army of the Cumberland, and Hooker’s troops. One of Grant’s first moves was to relieve Major General William S. Rosecrans, who had been vanquished at Chickamauga, as commander of the Cumberland army and replace him with Major General George H. Thomas. Opposing the Union forces were General Braxton Bragg and his Army of Tennessee, the victors at Chickamauga who had then put a stranglehold on Chattanooga.

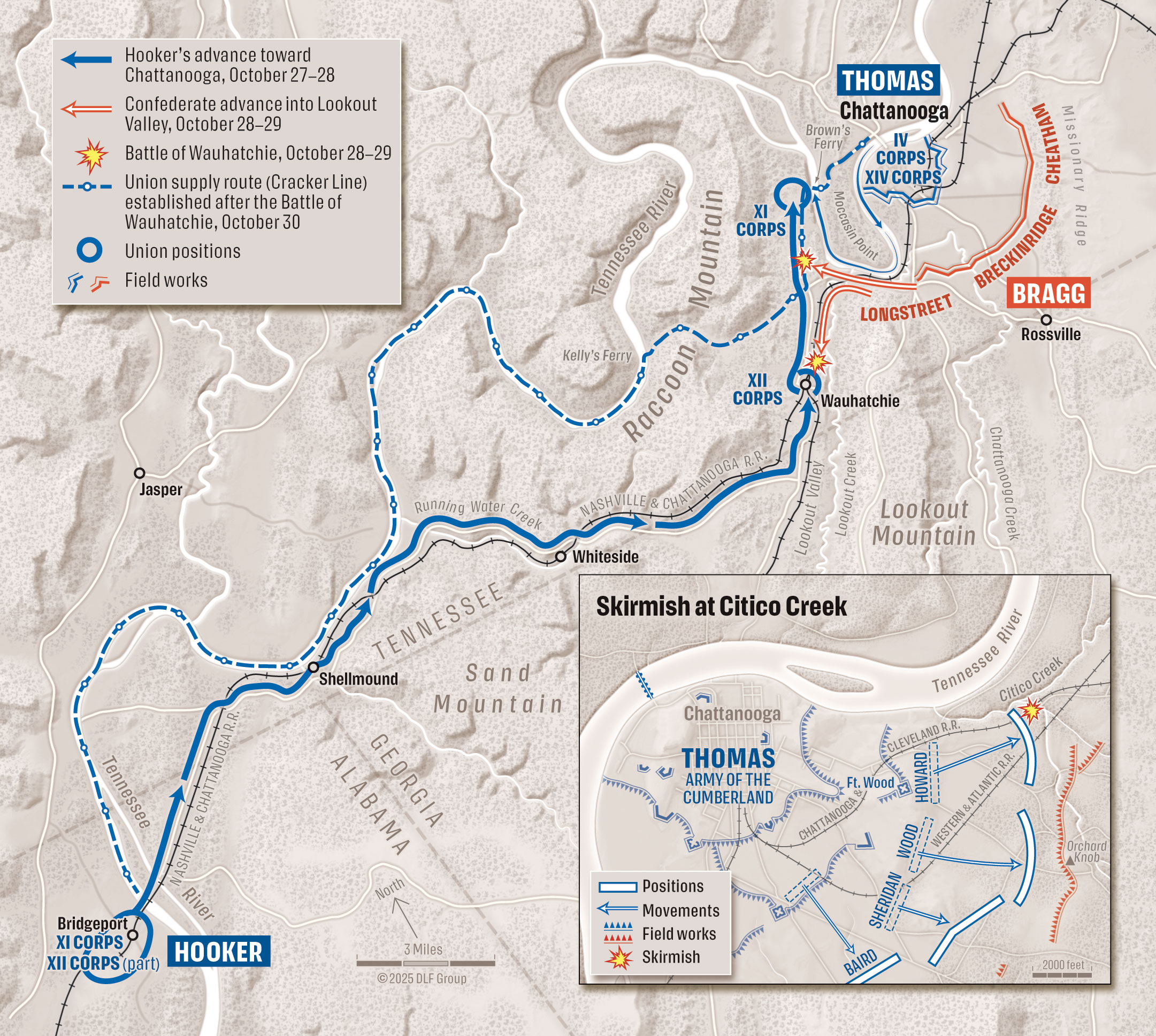

Library of Congress (Thomas); National Portrait Gallery (Bragg)

Library of Congress (Thomas); National Portrait Gallery (Bragg)George H. Thomas (left) and Braxton Bragg

What sort of combat would Hooker’s battle-hardened easterners face on their new terrain? For the 154th, it would include a skirmish at Wauhatchie, Tennessee, and a battle at Chattanooga in which the regiment’s involvement would amount in essence to a skirmish. Their colonel would write an official report of the fight for Chattanooga, and soldiers would describe it in their diaries and letters, but it wasn’t until the postwar years that a hidden aspect of the regiment’s role emerged in the reminiscences of veterans who were there.

The soldiers of the 154th New York spent more than three weeks at Bridgeport building corduroy roads, bridging streams, cutting ties for the railroad, and wondering at the poverty and backwardness of the rugged area. Finally, at daylight on October 27, Hooker’s command broke camp, crossed a pontoon bridge over the Tennessee River, and marched in the direction of Chattanooga. Their goal was to open a connection between Bridgeport, which was being transformed into a big Federal supply depot, and Thomas’ starving army trapped in Chattanooga. The brigade to which the 154th New York belonged, commanded by Colonel Adolphus Buschbeck (the First Brigade of Brigadier General Adolph von Steinwehr’s Second Division, of Major General Oliver Otis Howard’s XI Corps), took the lead and covered 20 miles during the day, camping for the night near Whiteside, a station on the Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad running between Bridgeport and Chattanooga.1

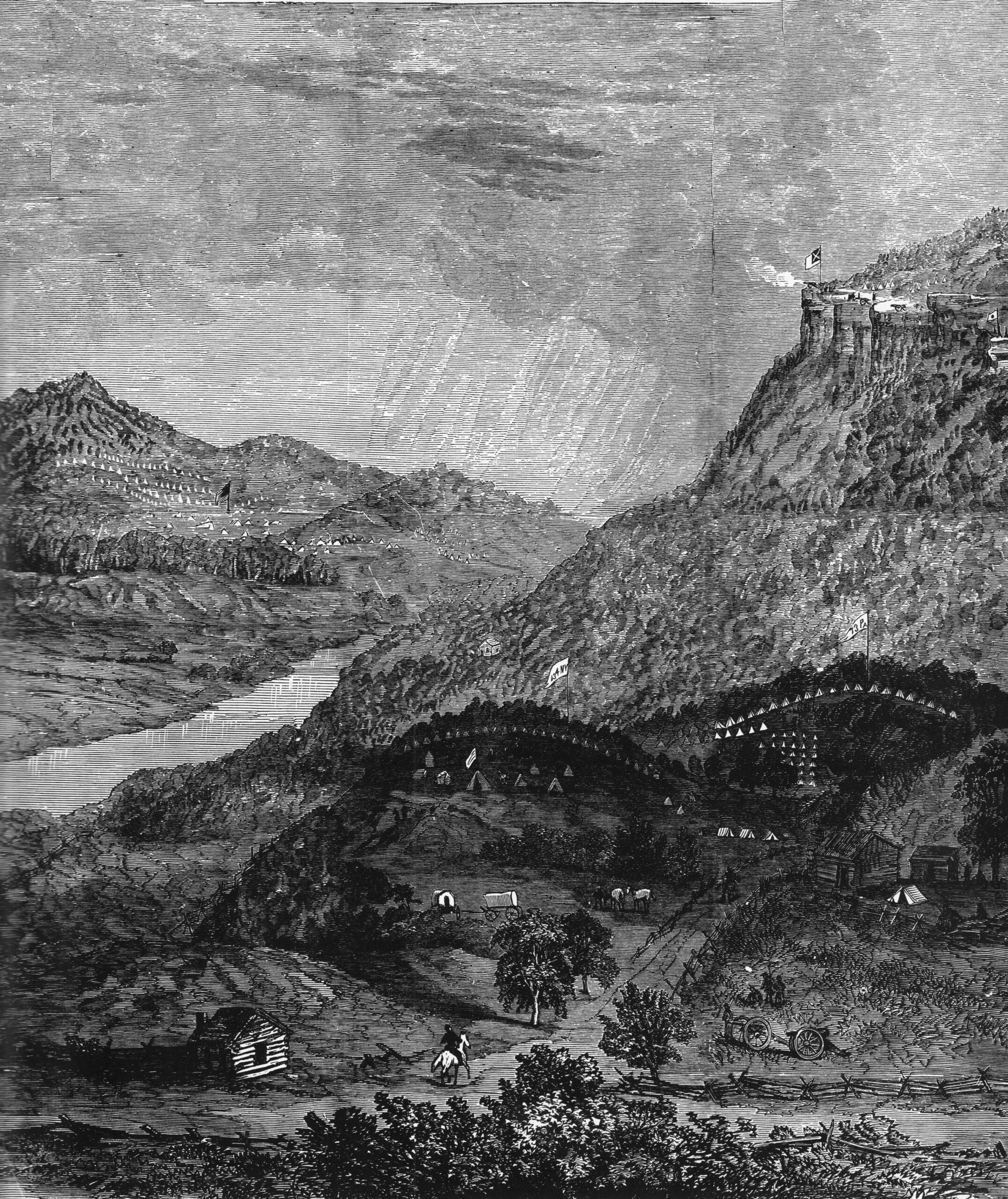

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated NewspaperColonel Adolphus Buschbeck’s brigade, which included the 154th New York Infantry, camped on the foothills below Lookout Mountain (as depicted in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper) for almost a month before taking part in the November 1863 fighting.

The next morning the men resumed the march early. Buschbeck’s brigade remained at the head of Hooker’s column. Around noon they came within sight of Lookout Mountain, from which the Confederates were shelling the Army of the Cumberland’s encampments. Following the railroad into Lookout Valley, they arrived at Wauhatchie, where a second railroad formed a junction, and they encountered Confederate pickets. The 73rd Pennsylvania Infantry of Buschbeck’s brigade was deployed as skirmishers, followed by the 154th New York. They met with little opposition until about three-quarters of a mile beyond where the railroad crossed Lookout Creek. There they found the 6th South Carolina Infantry in front and on top of a hill to the right of the road. Buschbeck ordered Major Lewis D. Warner, in command of the 154th, to deploy the regiment on both sides of the 73rd Pennsylvania. The two regiments charged up the hill, driving the South Carolinians down the other side and across Lookout Creek. One man of the 154th was wounded in the action: Private Hiram Straight of Co. C was shot in his left-hand and lost the little finger. “Our boys are in good spirits and quite jubilant over their afternoon’s performance,” Warner recorded in his diary that evening. “This was the first time they have had a chance to make the Rebs run, and the way they made the woods ring with their cheers was really amusing.”2

After the skirmish, the 154th marched back to the railroad and continued down the valley. The batteries atop Lookout Mountain attempted to shell the Federal column, but were unable to lower their aim sufficiently. As Buschbeck’s troops approached the Tennessee River, they were met by troops of the Army of the Cumberland, which had crossed the river at Brown’s Ferry to connect with Hooker’s men. The Cumberlanders greeted the easterners with shouts: “Hurrah! Hurrah! You have opened our cracker line!” Until that moment, the only line of supplies left open to the troops in Chattanooga had been 60 roundabout miles from Bridgeport over rough terrain, which was subject to harassment from Confederate cavalry. The result had been a half-starved Army of the Cumberland. The men had been reduced to two hardtack each per day, augmented by corn meant to feed horses and even the occasional dog. The arrival of the eastern troops opened a more direct route from Bridgeport and enabled a free flow of provisions into Chattanooga, thus breaking the siege. The men dubbed the new connection the Cracker Line.

For the men of the 154th New York, the day was an invigorating initiation into western theater campaigning. In the first charge they had ever made, they routed the enemy and they played an integral role in establishing the Cracker Line. That night the Confederates made a desperate charge on a XII Corps division at Hooker’s rear at Wauhatchie, but were repulsed. Buschbeck’s brigade marched toward the scene of the action, but were not engaged. As a precaution, the men remained under arms until daylight.

For nearly a month Hooker’s command lay in comparative quiet in Lookout Valley, while Grant perfected his plans for a breakout and waited for Sherman to arrive. The four regiments of Buschbeck’s brigade—the 134th and 154th New York and the 27th and 73rd Pennsylvania, soon to be joined by a fifth, the 33rd New Jersey—set up camps on a row of hills footing Lookout Mountain. The Confederates on the mountaintop attempted unsuccessfully to shell them. Most of their rounds overshot the Yankees, who came to consider the cannonading as a noisy but harmless part of their daily routine. Life for the members of the 154th New York once more settled into the familiar routine of drills and fatigue and picket duty.

With the arrival of Sherman’s troops in late November, Grant was ready to try to break the Confederate grip on Chattanooga. In his plan, Hooker would assault the Confederate left on Lookout Mountain, Sherman would attack the enemy’s right on the northern end of Missionary Ridge at Tunnel Hill, and Thomas would probe the center at Orchard Knob. The three commands, however, would be somewhat jumbled. A division each from Thomas’ and Sherman’s armies would fight with Hooker, while a division of Thomas’ would join Sherman’s force. The XI Corps would at first cooperate with Thomas’ men, but eventually join Sherman’s. At a lower level, Buschbeck’s brigade would be split for part of the battle. As things turned out, that circumstance was to the good fortune of the 154th New York.3

On November 22, Colonel Patrick Henry Jones, who had been wounded and captured at Chancellorsville, returned to the 154th and took command of the regiment. “It was very fortunate for us that he was with us,” Private Stephen R. Green of Co. E wrote. “He is a noble officer and knows his business and cares for his men.” That afternoon the XI Corps left its camps in Lookout Valley, the soldiers carrying three days’ cooked rations in light marching order. They crossed the Tennessee River at Brown’s Ferry, marched across Moccasin Point, recrossed the Tennessee on a pontoon bridge into Chattanooga, and bivouacked in fortifications southeast of the city.4

The Chattanooga Campaign

Chattanooga, Tennessee October–November 1863

In September 1863, the Army of the Potomac’s XI and XII Corps, under the overall command of Joseph Hooker, were transferred west to assist George H. Thomas’ Army of the Cumberland, then under siege by Braxton Bragg’s Confederate Army of Tennessee in Chattanooga, having been driven there after the Union defeat at Chickamauga. Hooker’s force landed at Bridgeport, Alabama, and made its way toward Chattanooga, its goal to open a supply line between Bridgeport and Thomas’ starving army. After clashing with Confederates at Wauhatchie in late October, Hooker’s men linked up with the Army of the Cumberland, opening the so-called “Cracker Line” to Thomas’ besieged troops. In November, Ulysses S. Grant, the overall commander of Union forces in the area, set his sights on driving Bragg’s army from their positions east of the city. As Union troops advanced in preparation for engaging Confederates dug in along Missionary Ridge, the 154th New York Infantry, part of the XI Corps, fought a memorable skirmish at Citico Creek on November 24.

“Our boys are in good spirits and quite jubilant over their afternoon’s performance. This was the first time they have had a chance to make the Rebs run.”

The next afternoon skirmishing commenced in front of Confederate outposts in the woods along the base of Missionary Ridge. As the XI Corps moved to its assigned position on the left end of the Federal line, Buschbeck’s brigade advanced in two lines, with the 154th New York on the left of the second line, following at supporting distance. “The enemy had a fair view of our forces which were marching towards them,” Private Colby M. Bryant of Co. A noted in his diary, “and I don’t wonder that they compared us to swarms of bees pouring forth from every direction in the valley towards them.” The 154th passed 500 yards in front of Fort Wood, which stood about a half mile southeast of the city limits, and was ordered to form in line of battle behind the Chattanooga and Cleveland Railroad. Buschbeck then ordered Jones to send a company of skirmishers across the railroad to Citico Creek. First Lieutenant James L. Harding led about 30 men of Co. B to the creek, where they were halted by heavy fire from Confederates on the opposite side. The two sides exchanged fire for about a half hour before the Confederates retreated out of range. None of Harding’s men were hurt.5

Around sunset Jones was ordered to relieve the 134th New York, which had advanced about 1,000 yards to an open field. Here the main body of the 154th remained overnight and constructed a line of rifle pits. Their breastworks were within 200 yards of the enemy’s.6

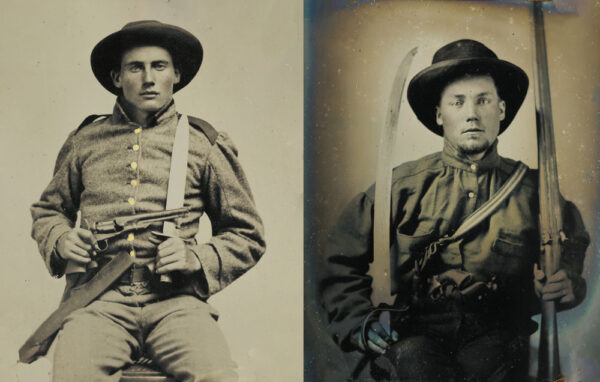

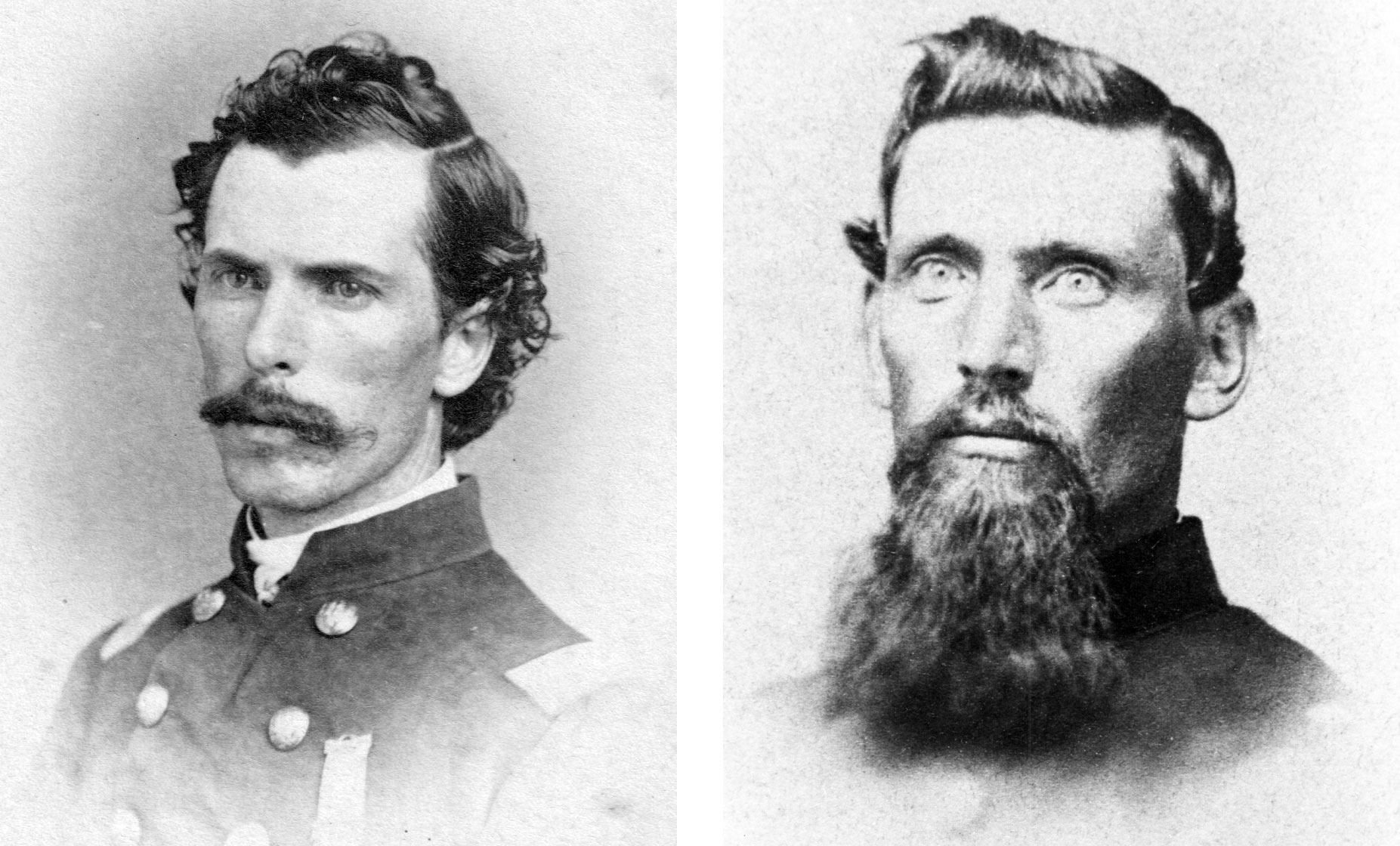

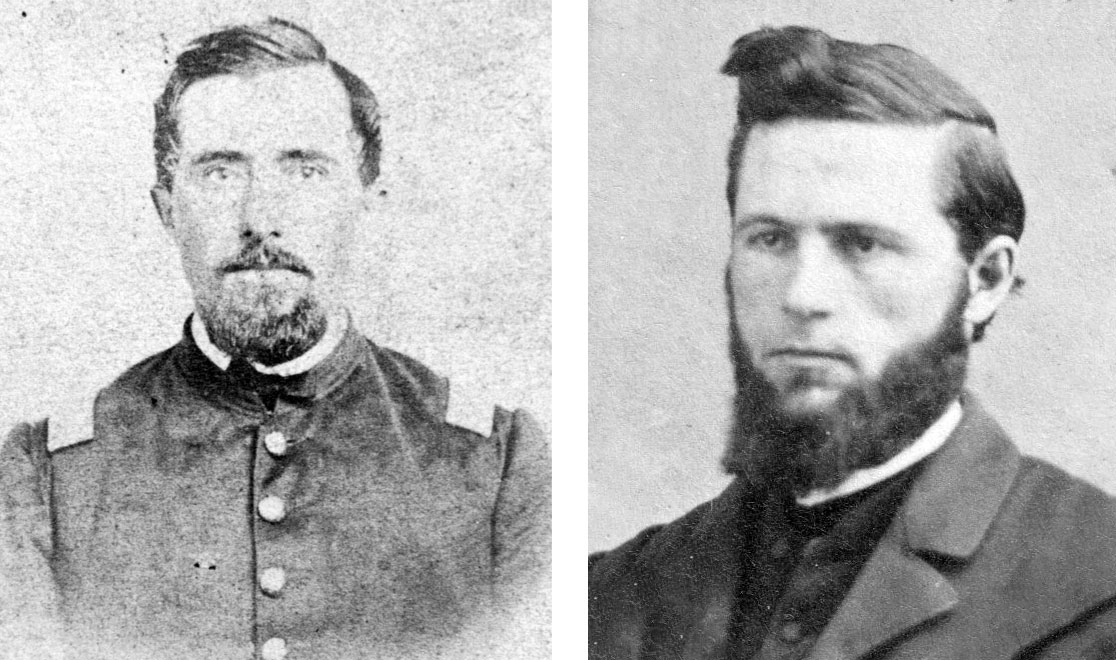

Author's Collection (Jones); William C. Welch Collection, Allegany, New York (Cheney)

Author's Collection (Jones); William C. Welch Collection, Allegany, New York (Cheney)Patrick Henry Jones (Left) And Harrison Cheney

A picket line was established in a small belt of woods beyond the open field. Companies A and F were assigned to the line, which was commanded by Captain Harrison Cheney of Co. D. Cheney also had his men patrol the banks of Citico Creek. Private Bryant reported, “We were kept all night keeping a close lookout to avoid surprise from the enemy, who we thought might attempt to take back what they had lost through the day, but everything remained quiet all night, except what noise was made by our men who were kept very busy making fortifications so as to hold what we had taken.” “We lay there all night without relief, and it was a bitter cold night,” wrote Private Milon J. Griswold of Co. F. “I lay on the railroad, right in sight of the Rebs, and I dare not stir, for if I did, they would pop me over.”7

At daybreak on November 24, Companies A and F were relieved as pickets by Companies E and H. When Cheney advanced his new line, a lively skirmish ensued. In his official report, which was written almost a month later, Jones stated the skirmish was “occasioned by the simultaneous relieving of the [Union and Confederate] pickets, the position of each becoming known to the other.” Six members of the 154th were wounded. “None are reported fatal thus far,” Jones noted in his report. Regimental comrades stated the wounds were not dangerous. As more than one member of the 154th later observed, the regiment was lucky to have had so few casualties during the battle.8

The regiment remained inactive for the rest of the day, while fighting raged elsewhere. Hooker took fog-covered Lookout Mountain, while Sherman hammered unsuccessfully at Tunnel Hill. On the morning of November 25, Generals Howard and von Steinwehr and Colonel Buschbeck, with the 33rd New Jersey and 27th and 73rd Pennsylvania Infantry regiments, went to join Sherman’s attack. Buschbeck’s men earned Sherman’s praise after suffering heavy casualties in the fighting. Jones was left in command of the 134th and 154th New York, which escaped the carnage inflicted on their comrades. Around 10 a.m. the XI Corps’ main line of battle moved forward. The 154th headed to the Western and Atlantic Railroad on the bank of Chickamauga Creek, dug rifle pits, and threw out pickets. Together with the 134th, the regiment acted as advanced guard during the night. During the day, Thomas’ men had made their stunning charge up Missionary Ridge, routing the Confederates and bringing the battle to a spectacular finish. At 6 a.m. on November 26, the two New York regiments reunited with the rest of Buschbeck’s brigade and marched to Chickamauga Station. The Battle of Chattanooga was over, the Union forces triumphant.9

Jones closed his official report of the Chattanooga battle by citing the “excellent conduct” of Captain Harrison Cheney in the skirmish near Citico Creek on the morning of November 24. “The conduct of both officers and men of the command then engaged was highly commendable,” Jones added, “but it was the good fortune of Captain Cheney to be posted in the most exposed position of the line, and he acquitted himself gallantly.” But exactly how “commendable” had the conduct of the 154th New York’s picket line been that morning?10

Governor’s Reception Room at the Minnesota State Capitol, St. Paul, Minnesota

Governor’s Reception Room at the Minnesota State Capitol, St. Paul, MinnesotaIn this painting by Douglas Volk, soldiers of the 2nd Minnesota Infantry sweep forward during the Union assault on Missionary Ridge.

The letters and diaries of soldiers who participated in the skirmish illuminate an aspect of the action that Jones omitted from his report. Bryant reported in his diary that Co. A was relieved as pickets at daybreak and returned to the main line of the regiment, behind the breastworks constructed overnight. “While going back,” he wrote, “the enemy opened fire on the men who relieved us and drove them back, but they were immediately sent out again.” In Co. F, Private Griswold was sheltered behind a small bush before the relief arrived. When a couple of potshots trimmed some leaves from the bush, he “dug out of that place, and got behind a stump.” The fresh pickets then advanced, “which did not suit the Rebs very well,” Griswold wryly observed, “and firing commenced, and we skedaddled for the breastworks, behind which the rest of our regiment lay. I tell you the cold lead fell around us like hail, but none of us [in Co. F] got a scratch.” In a brief diary entry for November 24, Griswold’s company comrade Private William D. Harper did not mention the skedaddle: “Called in off picket at daylight and stopped behind the rifle pits. Stayed there all day. Didn’t do any firing.”11

Private Green reported that when Companies E and H were posted on the picket line, “They [the Confederates] could see us and we did not know where they were (it was in the woods). They waited until we was about all posted, then they opened fire on us, wounding 3 men in each company.” Like Private Harper, Green did not mention the retreat. His company comrade Private Reuben R. Ogden did, however, in the terse entry for November 24 in his diary: “Went on picket at break of day. Was drove in. Case, Ash & Covey wounded. Fell back to the entrenchments. Advanced to the picket line & stood until night.”12

Bryant, Griswold, and Ogden described something Jones chose not to mention in his report—at daybreak on November 24, the regiment’s picket line had been driven in a skedaddle. Thirty years later, veterans of the 154th New York provided details of the episode in correspondence and interviews with a self-appointed historian of the regiment.

Edwin D. Northrup of Ellicottville, New York, would perhaps not have been the veterans’ first choice to chronicle their service when he announced his intention to do so in an 1878 flyer. Most of the veterans were conservative Republicans; Northrup was a Democrat who leaned toward socialism, an atheist who loathed organized religion, a supporter of women’s rights and suffrage, a prohibitionist, and a subscriber to magazines extolling vegetarianism and other fringe causes. He had other peculiarities: sleeping less than five hours a night, collecting and cataloguing litter he picked up from village streets, wearing nothing but blue clothing for more than 25 years. A lawyer, he had committed a homicide, but was acquitted of murder in the second degree on a plea of self-defense. He had an affection for the South and hatched a scheme to establish a colony of northerners in Georgia. He named his firstborn child Robert E. Lee Northrup—we can only wonder what the veterans of the 154th thought of that. Most egregiously, Northrup had not served in the war, although he was of age to do so. He had, in fact, been drafted in 1864, but had managed to escape serving.

Despite his eccentricities, Northrup received the cooperation of the veterans when he announced his intention to write a history of the 154th New York. He spent more than two decades researching and writing, but never published the book. His manuscript does not survive, but his correspondence with the veterans and notes he made during their personal interviews have been preserved among his voluminous papers, now housed at Cornell University’s Carl A. Kroch Library. Northrup took an interest in the skirmish of November 24 and gathered reminiscences of it from several of the participants.13

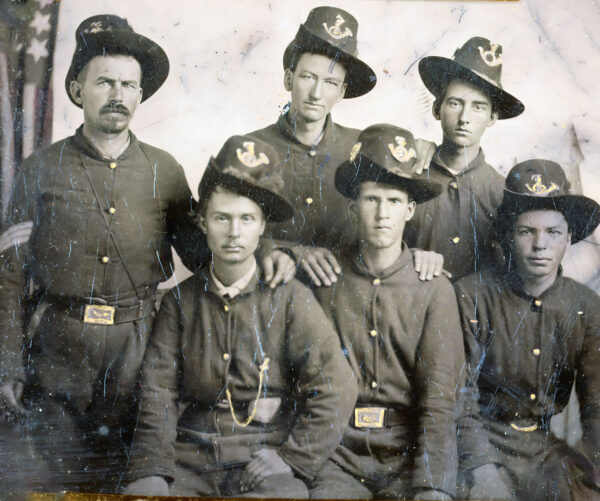

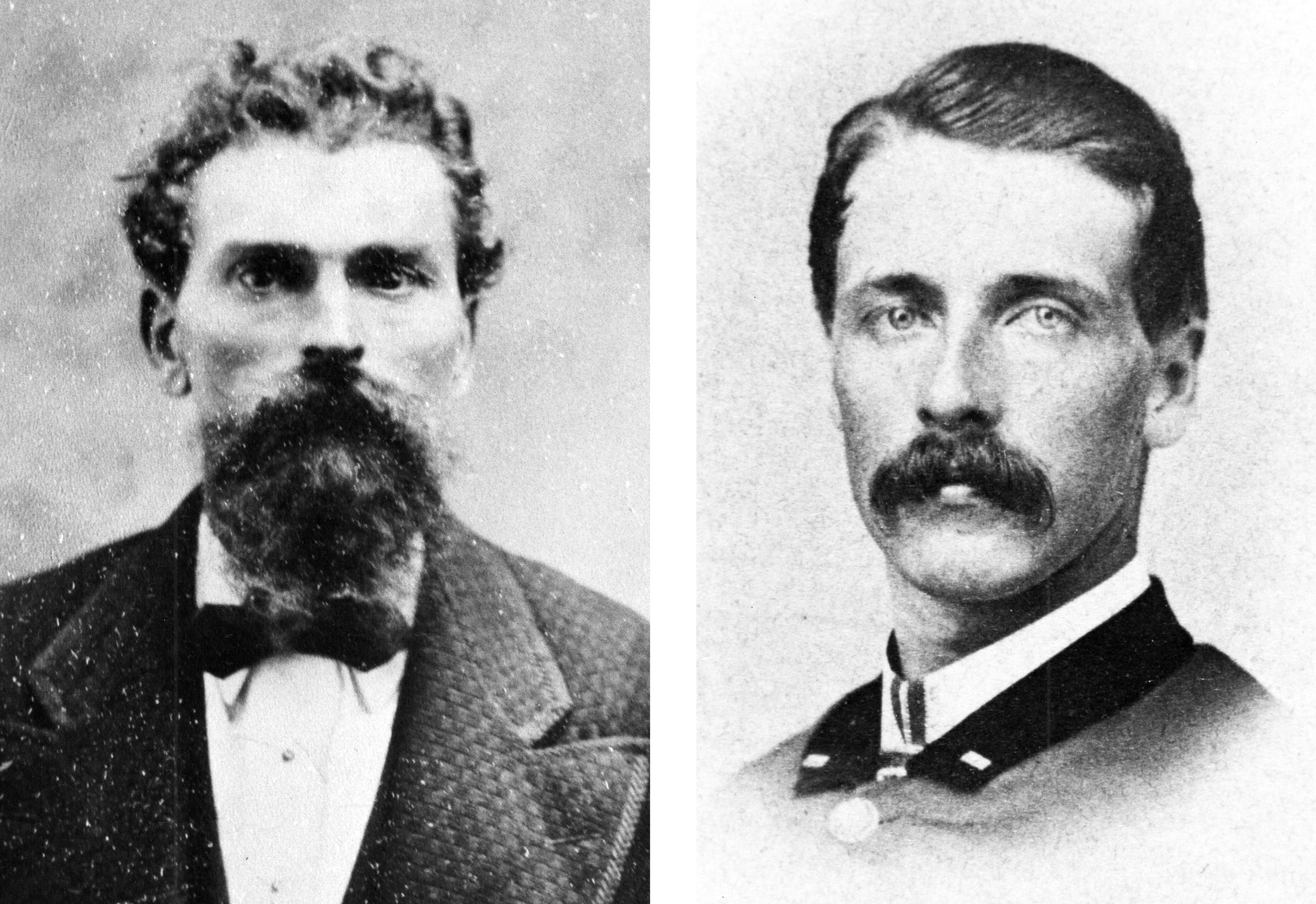

Luene A. Smith collection, Toledo, Ohio (Hoag); William C. Welch collection, Allegany, New York (Waterman)

Luene A. Smith collection, Toledo, Ohio (Hoag); William C. Welch collection, Allegany, New York (Waterman)Samuel Hoag (Left) And George C. Waterman

In 1896, Northrup interviewed Samuel Hoag, one of the men who had been wounded. Hoag recalled his Co. H being posted as pickets in the early morning darkness, facing Citico Creek, with Missionary Ridge to the right. A dilapidated post and rail fence was in the vicinity, and First Sergeant George C. “Guy” Waterman suggested the men use the rails to construct a slight shelter. They were engaged in the work when the Confederates opened fire. The only targets the Yankees had to aim at in the darkness were the flashes from the enemy’s muskets. Hoag heard Waterman shout to the company captain, Commodore Perry Vedder, “The Rebs are flanking us!” With that, Vedder ordered a retreat. Hoag had not gone far when a bullet struck his right calf, tearing through his pants and drawers and contusing his leg. The round tumbled into his shoe. On reaching the regiment’s breastworks, Hoag went to the regimental hospital for treatment.14

Waterman was working for The Central Gas Light Company in New York City when he described the incident in a letter to Northrup in 1895. After he and Hoag were posted as pickets, “the Rebs got on both our flanks and partly in our rear, and commenced to shoot damned close to our backs, and at that we got up and discovered a regiment of graybacks about 300 yards in our front. We blazed away at them and ran to the rear and up over a knoll and through a corn field to the railroad…. Sam had 17 bullet holes in his clothes, and one bullet was lodged in the bottom of one of his shoes.” Despite his specific and probably exaggerated report of the damage to Hoag’s uniform, Waterman oddly made no mention of Hoag being wounded.15

Earl Z. Bacon, a former private of Co. E, was a physician in Chicago when he corresponded with Northrup in 1895. According to Bacon, it was still dark when Co. E was posted that morning, and it was foggy as well. In the gloom, the men “passed through the rebel picket line, and what is more, had posted a number of men before we knew where we were.” When the fog lifted and the morning brightened, the shooting started. In the ensuing chaos, Private Andrew Hollister, “a little sawed-off Irishman,” according to Bacon, “fell into one of the rebel skirmish pits on top of a Johnny Reb, and making friends with the Reb, he stayed there until the Rebs retreated, when he let the Reb go according to agreement, and Andy came back to us.”16

Salmon W. Beardsley was farming and working as an officer of a creamery company in the vicinity of Lincoln, Nebraska, when he corresponded with Northrup in 1893 and 1895. He was a first lieutenant in command of Co. E at the time of the Chattanooga battle. In four lengthy letters to Northrup, Beardsley provided a detailed account of the happenings during the early morning skirmish on November 24.

As Beardsley remembered it, five companies were sent to the picket line: E, H, C, D, and another he was unsure of. That Companies E and H were detailed is supported by other evidence. If the other companies were involved is uncertain. It seems unlikely that half the regiment would have been assigned to picket duty, although the fact that Captain Cheney of Co. D commanded the line makes one wonder. In any case, according to Beardsley, the acting regimental adjutant, First Lieutenant John Mitchell, led the pickets to their post. The moon was almost full—a lunar eclipse would occur the next night—but was obscured by clouds and the night was dark.

The pickets followed the railroad and entered a patch of woods. Beardsley remarked to Mitchell that he thought they were getting beyond the established picket line. Mitchell disagreed, and on they went. “Before we had advanced fifty yards farther,” Beardsley wrote, “the rebels fired upon us.” The pickets halted and immediately filed to the left of the railroad, at right angles to the track. Company E was in the lead and consequently formed the left end of the picket line, with no connection or support on their flank. “Every man in the company was on the alert all night,” Beardsley recalled. Having posted the line, Mitchell returned to regimental headquarters behind the breastworks, well to the rear. Things were quiet until daybreak.

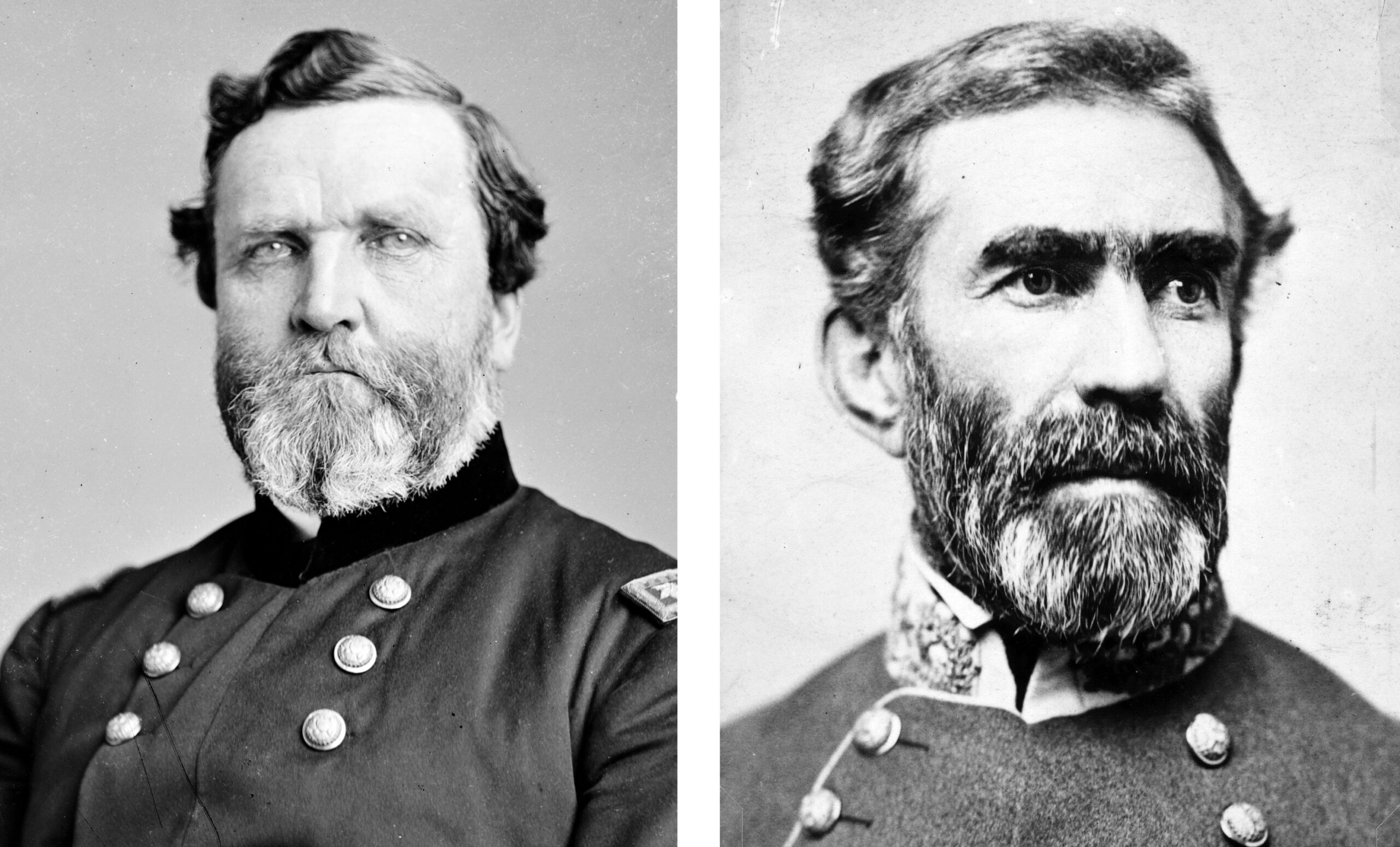

Mildred Edmunds collection, Farmersville Station, New York (Mitchell); Author’s collection (Vedder)

Mildred Edmunds collection, Farmersville Station, New York (Mitchell); Author’s collection (Vedder)John Mitchell (Left) And Commodore Perry Vedder

When the Confederates opened fire and advanced on the pickets, Beardsley ordered Co. E to give them a volley and then retreat, loading their muskets as they fell back. After backtracking about 150 yards, the men took cover behind some trees and gave the enemy another round. But the Confederates overlapped the left of the line, and Beardsley ordered his men to fall back again. They halted in a deep ravine and gave their pursuers another volley before scurrying across the ravine. At its lip, Beardsley ordered his men to lie down, and when the Confederates emerged from the woods, Co. E unleashed another volley. At that moment, the rebel yell was heard to the right; Beardsley saw the pickets in that sector were falling back to the regiment’s main line in the breastworks, and the enemy was swinging around to cut off his men. He ordered them to retreat on the double-quick across the open field to the entrenchments, “and it was a hurrying time to see who would get there first, the rebels, or we. Our men in the trenches saw the movement and opened on the rebels in time to save us. The boys out-ran me and I was the last one in.”

When Beardsley reached the safety of the breastworks, he was met by Colonel Jones, who greeted him by saying, “Lieutenant Beardsley, I am surprised at you. I thought you was a brave man and would not run.” Beardsley replied, “Colonel Jones, if I am a coward, take my sword and give me a trial,” unbuckling his sword as he did so. “What did you come in for?” Jones asked. “I came in to save my company,” Beardsley responded, “and I would do the same thing over again.” He pointed out that his company was the last to reach the breastworks, that the other companies had got there while his was still on the farther side of the field. When Beardsley declared, “Colonel Jones, you can put some other man in command of my company, until I am vindicated,” Jones smiled and said, “Lieutenant, you did right, but I’ll be damned if the other officers did right in retreating so suddenly.”

The colonel then ordered, “Officers of the picket line, deploy your men and retake that line.” The officers jumped over the breastwork and called for their men to advance. They drove the Confederates back, made a connection with other troops on their right, and held the line near Citico Creek until relieved that night.

When Beardsley had an opportunity to ask Vedder what Jones had said to him, “Vedder admitted that Col. Jones gave them hell and told them they were a set of damned cowards to retreat so suddenly.” But when Jones found that the pickets had advanced beyond the established picket line and were unsupported on both flanks, he said Lieutenant Mitchell had made a mistake in placing the line, and he did not blame Beardsley or Vedder for falling back.

“In regard to Col. Jones in his report making special mention of Capt. Harrison Cheney on that occasion,” Beardsley informed Northrup, “it proves what I have always believed of him, that he would do equal and exact justice to all.” Cheney “was the ranking officer and of course was in command of the line and as such would have to bear the blame in a greater degree than anyone else if the conduct of the line was not what it should be, and we all knew him to be brave and cool.” Furthermore, Beardsley declared, “We were all entitled to share in whatever of praise he received according to the position we occupied, down to [a] private in the rear rank.”17

How Colonel Jones, Captains Cheney and Vedder, Lieutenant Mitchell, and others would have parsed the events of the morning is unknown. After learning the situation that faced the pickets when attacked, Jones decided not to mention the skedaddle in his official report. After all, his men had retaken the advanced line after they regrouped. For Jones, it was enough to mention the “sharp fire” of the skirmish, and “a loss of 6 men wounded … the only loss sustained by my regiment during the several days embraced by this report,” and conclude by praising the commendable conduct of the officers and men engaged.18

After providing Northrup with such a detailed and unvarnished account of the affair near Citico Creek, Beardsley closed one of his letters on the subject by stating, “It was the only time that we ever got in such a box during my service.”19

Mark H. Dunkelman has written and lectured extensively on 154th New York history. He spearheaded a drive to erect a regimental monument at Chancellorsville, and created the mural at Coster Avenue in Gettysburg that depicts the regiment in action on the battle’s first day. His work was spotlighted in our Winter 2014 issue.

Notes

1. Mark H. Dunkelman and Michael Winey, The Hardtack Regiment: An Illustrated History of the 154th Regiment, New York Infantry Volunteers (New Brunswick, NJ, 1981), passim.

2. Lewis D. Warner to John T. Sprague, December 24, 1863, in Regimental Letter Book, Ellicottville (NY) Historical Society; L.D. Warner diary, October 28, 1863, John L. Spencer collection, Canandaigua, New York; L.D. Warner to Friend Fay, November 5, 1863, unidentified newspaper clipping, New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center, Saratoga Springs, NY; Peter Cozzens, The Shipwreck of Their Hopes: The Battles for Chattanooga (Urbana, 1994), 72.

3. Dunkelman and Winey, The Hardtack Regiment, 92–95; Cozzens, The Shipwreck of Their Hopes, 72–125; Wiley Sword, Mountains Touched with Fire: Chattanooga Besieged, 1863 (New York, 1995), 127–171; Steven E. Woodworth, Six Armies in Tennessee: The Chickamauga and Chattanooga Campaigns (Lincoln, 1998), 161–179.

4. Stephen R. Green to his wife, December 28, 1863, Phil Palen collection, Gowanda, New York; Report of Colonel Patrick H. Jones in United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies 129 vols. (Washington, 1880–1901), Series 1, Volume 31, Part 2, 366–367 (hereafter cited as Jones’ report, OR).

5. Jones’ report, OR; Colby M. Bryant diary, November 23, 1863, Bruce H. Bryant collection, Salamanca, New York (hereafter cited as Bryant diary).

6. Jones’ report, OR.

7. Jones’ report, OR; Bryant diary, November 23–24, 1863; “Interesting letter from the 154th,” Fredonia Censor, February 24, 1864, quoting letter of Milon J. Griswold of December 24, 1863.

8. Jones’ report, OR; William Charles to his wife, November 27, 1863, Jack Finch collection, Freedom, New York.

9. Jones’ report, OR; Report of Adolph von Steinwehr in OR, Series 1, Volume 31, Part 2, 359; William T. Sherman, Memoirs of General William T. Sherman by Himself (Bloomington, 1957), 1: 375, 383–384.

10. Jones’ report, OR.

11. Bryant diary, November 24, 1863; “Interesting letter from the 154th”; William D. Harper diary, November 24, 1863, Raymond Harper collection, Dunkirk, New York.

12. Green to his wife, December 28, 1863; Reuben R. Ogden diary, November 24, 1863, Bradley J. Eide collection, Chesterfield, Virginia.

13. Mark H. Dunkelman, Brothers One and All: Esprit de Corps in a Civil War Regiment (Baton Rouge, 2004), 269–275; Edwin Dwight Northrup Papers, #4190, Department of Manuscripts and University Archives, Cornell University (cited hereafter as EDN Papers).

14. Samuel Hoag interview, January 6, 1896, EDN Papers.

15. Guy C. Waterman to EDN, September 3, 1895, EDN Papers. Waterman also described the incident to EDN in a brief account, “The Sharpshooters Duel,” in which he stated Sergeant Thomas S. Willis was with him and Hoag.

16. Earl Z. Bacon to EDN, September 15 and November 24, 1895, and January 18, 1896, EDN Papers.

17. Salmon W. Beardsley to EDN, October 5 and November 10, 1893, and October 22 and November 9, 1895, EDN Papers.

18. Jones’ report, OR.

19. Beardsley to EDN, October 22, 1895, EDN Papers.