June•teenth | noun | June 19 observed as a legal holiday in the United States in commemoration of the end of slavery in the U.S. NOTE: The federal name for this holiday according to the United States Code is Juneteenth National Independence Day. It is also called Black Independence Day, Emancipation Day, Freedom Day, Jubilee Day, and Juneteenth Independence Day.1

Library of Congress

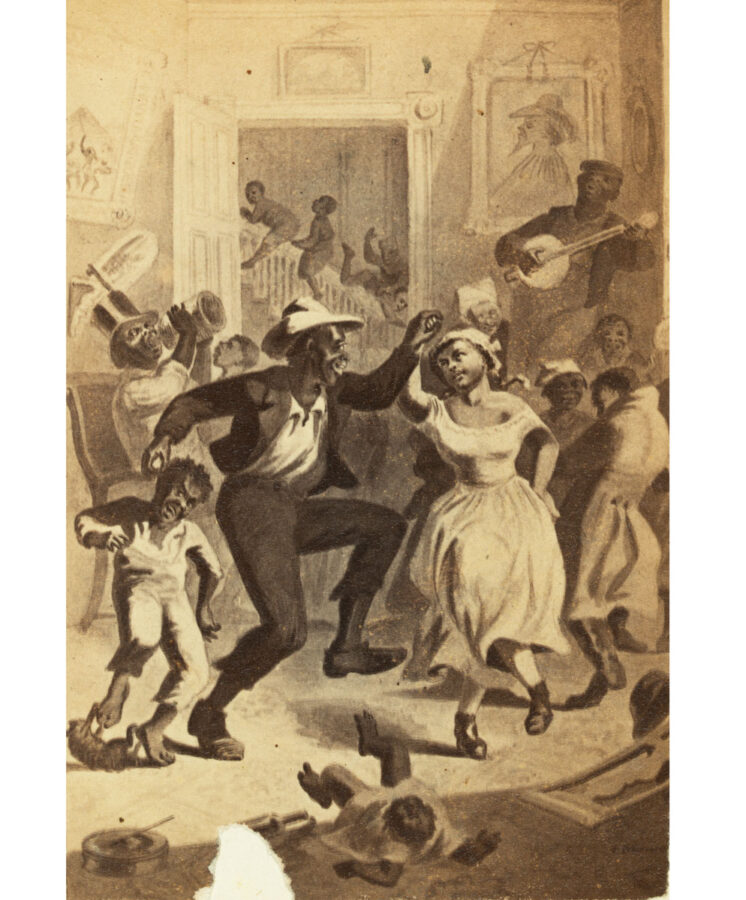

Library of Congress“Juneteenth” is the name given to the day—June 19, 1865—when Major General Gordon Granger informed enslaved people in Galveston, Texas, of the freedom that had been granted them more than two years earlier by the Emancipation Proclamation. Shown here: An 1865 print titled “The Day of Jubelo” depicts African Americans—possibly recently freed slaves—celebrating in a plantation house.

On June 19, 1865, over two months after Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox Court House, Major General Gordon Granger issued General Order Number 3: “The people are informed that in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property, between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them, become that between employer and hired labor. The freed are advised to remain at their present homes, and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts; and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.”2 Granger, commander of the District of Texas, and his Union soldiers had arrived the day before in Galveston, and he wasted no time informing the region’s still-enslaved people of their official liberation.

On January 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln had issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared that “all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.”3 The act’s scope was considered limited and people across the Confederacy were held in bondage as the Civil War dragged on. Union troops liberated some slaves and other African Americans chose self-liberation, but slaveholders in the Confederate South refused to recognize the proclamation—even after Lee’s surrender. For people enslaved across the South, their enslavement gradually came to an end over the spring and early summer of 1865, facilitated by Union commanders.

After lifetimes of bondage, the black men, women, and children of Galveston and the surrounding area were finally free on June 19, 1865. Henry Lewis had learned of his emancipation on March 3, but his enslaver refused to “tu’n us loose den.” He recalled years later that the Lone Star State “was de las’ state to tu’n de slaves free. W’en dey didn’ let ’em go in March, de Yankee sojers come in June and mek ’em let ’em go.” On June 20, Lewis’ overseer “read de papers out and tell us we’s free as he is, and we kin go.” Having received nothing for his approximately 20 years of enslaved labor, Lewis walked off the plantation empty-handed.4 In nearby San Antonio, Union soldiers swarmed the streets on June 19 and, one man recalled, “everybody went wild. We all felt like heroes, and nobody had made us that way but ourselves. We were free. Just like that, we were free.”5 Mattie Gilmore remembered when the “paper came to make us free…. Some of the slaves were laughing and some crying, and it was a funny place to be.”6 But many white Texans reacted with rage and unleashed a torrent of violence against the celebrating freedmen in 1865—and for decades after.

On June 19, 1866, Galveston’s black community gathered to commemorate the historic anniversary with large church gatherings, prayer services, picnics, dances, and political rallies. As with the Fourth of July, these celebratory Emancipation Day events—as they were commonly called in both white and black communities—became a yearly occasion in many parts of Texas. In addition to joyful celebration and time off work, these civil events featured political speeches, voter education, and encouraged black Americans to assume an active role in the political arena. According to historian Elizabeth Turner Hayes, Emancipation Day “took on broader implications for citizenship.”7 As the years went on, black Americans pooled their resources to purchase land for their own “emancipation grounds.” In 1872 in Houston, African Americans bought a parcel of land for $1,000 and named it “Emancipation Park.” Every year the local black community gathered there to celebrate the anniversary of June 19.

Black communities across the United States marked the various dates of their emancipations. As black Texans began migrating to the surrounding states and, later, to the North and West in the 20th century’s Great Migration, they brought with them the custom of celebrating Emancipation Day on June 19. Gradually the day took on a new name: Juneteenth. It first appeared in print in 1890, when the Galveston Daily News, reportedly quoting the black-owned Beaumont Recorder newspaper, wrote, “For Galveston to send abroad for orators for its coming ‘Juneteenth’ is like carrying coal to Newcastle. There are about as good speakers—persons who know all about English as she is spoke—in the city by the sea as anywhere.”8 Five years later, a black-owned newspaper on the Kansas frontier reported, “the citizens of this city and vicinity, native Texans, assembled in the fair grounds to commemorate the thirtieth anniversary of liberation of the bonded Afro-American[s] of Texas.” “Closely following” myriad speeches, a prayer from Reverend J.R. Ransom, and “an animated game of base ball,” the “happy throng repaired to their homes expressing themselves as highly pleased with their first Juneteenth celebration.”9 By the early 20th century, groups of African Americans across the United States were celebrating June 19. In 1916, The Book of Texas formally defined the celebration for its mostly white readership: “When the war ended and the Federal soldiers finally took possession, the proclamation freeing the negroes was made June 19, 1865, thus establishing a negro holiday known as the ‘Juneteenth,’ celebrated each year in fitting style throughout the state by the black man and all his people.”10

Since 1865, black communities have kept the memory of Juneteenth or Emancipation Day alive. “Whether they are rural or urban, their local specificity, and their hiddenness from those who would misunderstand their gravity, have made Juneteenth events special and enduring,” notes historian Tiya Miles.11 Some communities continue to host additional annual celebrations honoring their local heritage; in the capital, D.C. Emancipation Day (which was April 16, 1862) annually includes a public concert, parade, and festival.12

On June 17, 2021, President Joseph R. Biden Jr. signed the “Juneteenth National Independence Day Act,” making Juneteenth a federally recognized holiday. “On Juneteenth, we recommit ourselves to the work of equity, equality, and justice. And, we celebrate the centuries of struggle, courage, and hope that have brought us to this time of progress and possibility,” proclaimed Biden. “Juneteenth marks both the long, hard night of slavery and discrimination, and the promise of a brighter morning to come….”13 In 2023, Galveston hosted, among other events, a reenactment of the first Emancipation Day celebration, a public Emancipation Proclamation reading, and a festival and picnic at Menard Park. Juneteenth is publicly celebrated in places as disparate as Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts; Cleveland, Ohio; Los Angeles, California; and Hampton Roads, Virginia.14 People of all backgrounds and ethnicities will come together again this Juneteenth to reflect on the country’s long history of slavery, emancipation, and persistent racial inequality.

Tracy L. Barnett will receive her Ph.D. in American History from University of Georgia in May 2025. Rifles—their meaning to men and their availability in 19th-century America—are at the center of her academic scholarship. With her feline familiar, Barnett, lives in Washington, D.C.

Notes

1. “Juneteenth,” Merriam Webster (merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Juneteenth).

2. Galveston Tri-Weekly News, June 20, 1865.

3. Abraham Lincoln, “Emancipation Proclamation,” January 1, 1863.

4. Around 2,300 formerly enslaved men and women were interviewed by the Federal Writers’ Project between 1936 and 1938. A federal program supported by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, this Great Depression-Era project—housed under the umbrella of the Works Progress Administration, later renamed the Work Projects Administration (WPA)—interviewed formerly enslaved individuals, asking a series of questions about daily life, work, religion, and cultural customs. While not without flaws, these sources offer a lens into the black community at the moment of emancipation. Henry Lewis, Image 3 of Federal Writers Project: Slave Narrative Project (hereafter FWP–SNP), Vol. 16, Texas, Part 3, Lewis-Ryles (1936), Library of Congress, Manuscript/Mixed Material.

5. Felix Haywood, FWP–SNP, Vol. 16, Texas, Part 2, Easter-King (1936).

6. Mattie Gilmore, FWP–SNP, Vol. 16, Texas, Part 2, Easter-King (1936).

7. Elizabeth Turner Hayes, “Juneteenth: Emancipation and Memory,” in Gregg Cantrell and Elizabeth Hayes Turner, eds., Lone Star Pasts: Memory and History in Texas (College Station, 2007), 157.

8. Galveston Daily News, May 22, 1890.

9. Parsons Weekly Blade (Parsons, Kansas), June 22, 1895.

10. H.Y. Benedict and John A. Lomax, The Book of Texas (New York, 1916), 26.

11. Tiya Miles, “As Juneteenth Goes National, We Must Preserve the Local,” The New York Times, June 16, 2023.

12. “DC Emancipation Day,” DC.gov (emancipation.dc.gov).

13. Joseph R. Biden Jr. “A Proclamation on Juneteenth Day of Observance, 2021,” The White House Briefing Room, June 18, 2021.

14. Shayla Martin, “From Martha’s Vineyard to Cleveland: Celebrating the Day Slavery Ended,” The New York Times, June 9, 2023.

Related topics: African Americans, emancipation