National Portrait Gallery

National Portrait GalleryJohn Ericsson

Captain Fauon was worried. His ship, the chartered steamer Ericsson, was laboring in winter seas 40 miles south of Cape Hatteras. Ericsson had been towing four new obstruction-clearing rafts south from New York to Port Royal, South Carolina, to assist in the Union military’s siege of Charleston.

One raft had come loose and drifted away during the first leg of the voyage, to Fort Monroe, at Hampton, Virginia. There Faucon had resecured the remaining rafts, linking them in a line towing behind Ericsson. This he did with heavy chain passed through the center of each raft, from one to the next, with the first raft astern secured to Ericsson’s towing bits by four nine-inch hawsers. Anticipating that one or more rafts might become adrift anyway, Faucon fitted each with a blue-and-red flag on a 14-foot flagstaff to make the rafts easier to spot.1

Ericsson steamed out of Hampton Roads on February 10, 1863, and by dusk the steamer and its three rafts passed Cape Henry, 10 miles to the west. But while the weather had been fine when Ericsson sailed, it quickly began to deteriorate. On the afternoon of the following day, February 11, a two-inch shackle broke, setting the rafts adrift. Ericsson stopped and lowered a boat whose crew managed to get the rafts secured and under way again.2

The next day, the winds were blowing from the southeast and Ericsson was barely able to maintain enough speed to make steering with the ship’s rudder effective. Even at that the leading raft, the one directly secured to the ship, kept burying itself in the rolling swells, further adding to the drag of the heavy timber rafts. Around 10:45 that evening Faucon realized the second and third rafts in tow had broken away from the first, and were lost in the darkness. Daylight confirmed his suspicions; the two trailing rafts were gone, and the flagstaff of the one remaining had been swept away.3

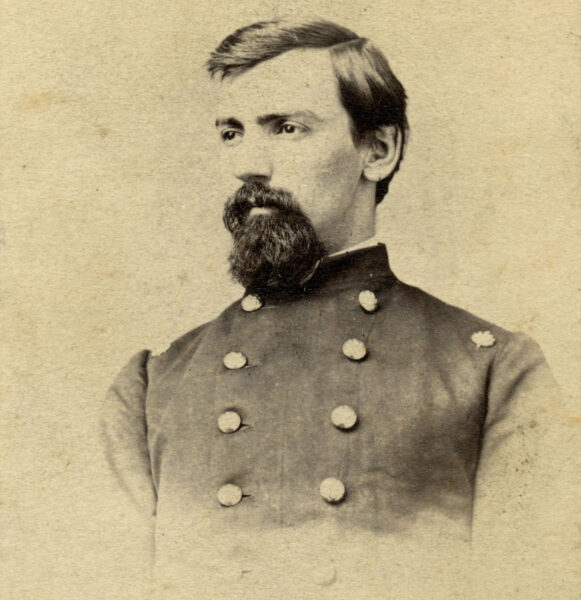

Library of Congress

Library of CongressIn February 1863, Captain Edward Horatio Faucon was charged with towing four enormous rafts—created by USS Monitor inventor John Ericsson—intended to help the Union navy clear obstructions in Charleston Harbor. Three of the four wouldn’t reach their destination, the first raft coming loose and drifting away during the first leg of the journey to Fort Monroe (pictured here).

Ericsson finally put into Port Royal on February 18 with just one of the original four rafts remaining. Faucon’s report to Rear Admiral Samuel Du Pont, commanding the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, was blunt. It was impractical, he wrote, to attempt to tow similar rafts in winter seas, and even in calmer seas towing more than two should not be attempted. “When it blows fresh,” he wrote, “[and] you keep steerage way on the ship … the rafts will bury in the sea, and if you seek to remedy this by slowing down, your ship becomes unmanageable.” At no time, Faucon concluded, should towing similar rafts be attempted at a speed of more than 3½ knots, or about 4 mph—a brisk walking pace. Du Pont endorsed the report, noting that Faucon had “exercised all care and vigilance, doing your duty faithfully and well, the loss of the rafts being beyond your control.”4

Edward Horatio Faucon’s reputation undoubtedly influenced Du Pont’s assessment. Faucon, 57, was a master seaman, by the 1860s already somewhat famous for Richard Henry Dana’s account of him in the popular memoir Two Years Before the Mast, published more than two decades before. Dana found Faucon, as master of the merchant brig Pilgrim, to be well-educated and able to quote Virgil in Latin, but also comfortable interacting one-on-one with his crew, a social flexibility uncommon aboard ship in that era. Dana wrote that Faucon “knew what a ship was, and was as much at home in one as a cobbler in his stall. I wanted no better proof of this than the opinion of the ship’s crew, for they had been six months under his command, and knew him thoroughly, and if sailors allow their captain to be a good seaman, you may be sure he is one, for that is a thing they are not usually ready to admit.”5

Still, Faucon must have been frustrated by the loss of the three rafts. It would mean a change in the Union plans for assaulting the Confederate strongpoint at Charleston, or at least a delay until new rafts might be built and delivered, at great additional expense and effort. Faucon wouldn’t have been blamed if he had thought to himself that he hoped never to see one of those rafts again—but that was not to be, either.

Back in the fall of 1862, John Ericsson, the irrepressible and irascible Swedish émigré who had created the turreted ironclad USS Monitor, turned his attention to the capture of Charleston, a primary target for Union forces for strategic, economic, and political reasons. The Union navy had ordered a fleet of monitors to be constructed, based on Ericsson’s original, but the inventor was not convinced they would be the key to taking Charleston. At the end of September he wrote to Assistant Secretary of the Navy Gustavus Fox that “the number of fifteen-inch guns, rather than the number of vessels, will decide your success against the stone forts [at Charleston].” A few weeks later Ericsson wrote again to Fox, saying that he understood the challenge the Navy Department anticipated was the presence of physical obstructions placed by the Confederates in Charleston Harbor, like pilings. Rather than attempt to reduce the forts around the harbor with artillery, Ericsson instead focused on getting past the obstructions, clearing a path to allow the navy’s monitors to bypass the forts entirely. He initially proposed that a heavy, iron-reinforced raft, affixed to the bow of one of the navy’s new monitors, could do the job by “continuous butting and backing,” like an angry goat, under the cover of darkness. Naturally Ericsson offered to design such a raft.6

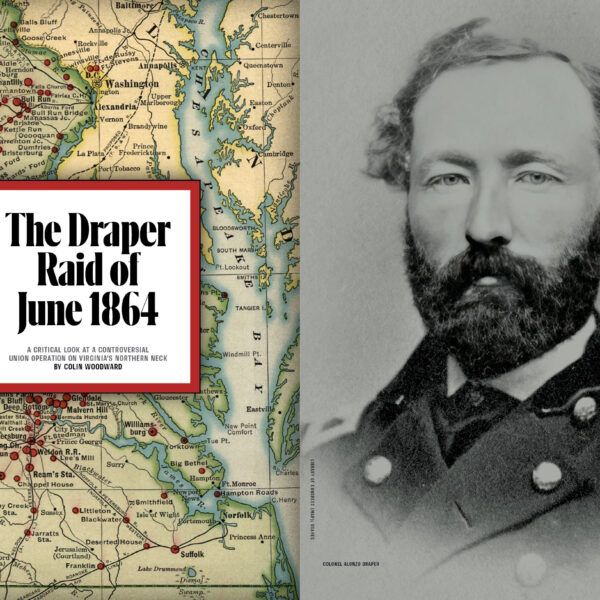

Andrew W. Hall

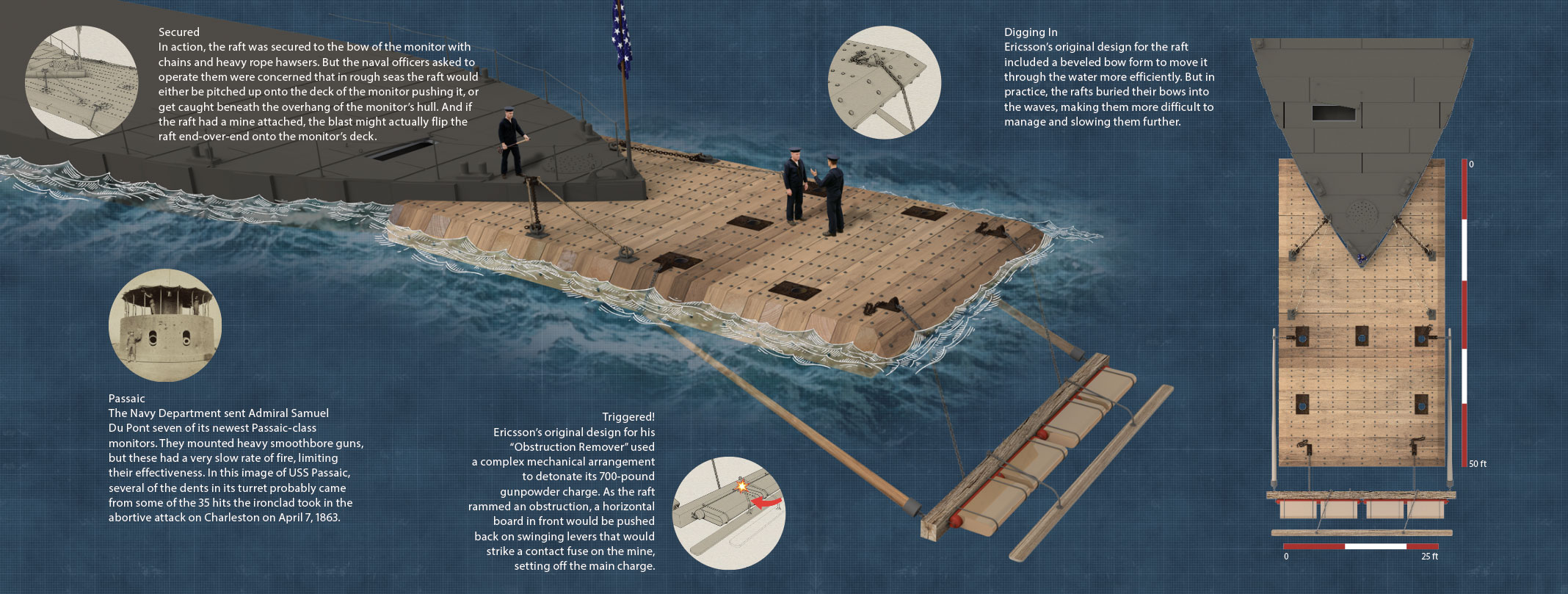

Andrew W. HallThe “Obstruction Remover” | A closer look at John Ericsson’s innovative—yet cumbersome and impractical—raft intended to help the Union navy break through the obstructions of Charleston Harbor.

The “Boot-Jack”

Perhaps not surprisingly, the craft that emerged from Ericsson’s drawing board was far more complex than the initial concept that would knock a path through harbor obstructions with simple, repetitive poundings of “butting and backing.” The rafts themselves were enormous, and enormously heavy. They measured 50 feet long by 27 feet wide, comprised two layers of 18-inch square white pine timbers laid at right angles to each other, all held together by massive iron through-bolts. The aft end of each raft was cut out with a 20-foot-long V-shaped notch to receive the pointed bow of the monitor to which the raft would be secured. The edges of the rafts were beveled, to give them some streamlining. Ericsson named his design the “Obstruction Remover.” Yankee sailors, observing the triangular cutout to fit the bow of a monitor, called the rafts “boot-jacks.” The Confederates would end up calling them “devils.”7

In the most notable change from his original concept, Ericsson fitted the bow of each raft with a horizontal boom that could be lowered in front, as if to sweep ahead of the raft. To this beam he affixed two cast iron cylinders, each 10 inches in diameter and 11 feet long, that spanned the entire width of the raft and boom. Each cylinder contained 350 pounds of powder that would be set off when a second, much lighter boom suspended from the first, contacted a hard surface, say a harbor obstruction. The momentum of the raft and the monitor behind it would swing the lighter boom back into the heavier one with the explosives attached, setting off contact fuses that would detonate the full 700 pounds of gunpowder. To direct the main force of the blast into the obstruction, Ericsson fitted the explosive cylinders with air chambers on their front side, which he believed would direct most of the blast forward, away from the raft and the ship behind it.8

Unfortunately the natural buoyancy of the rafts’ timber was mostly offset by their iron through-bolts, chains, and other iron fittings, so that they rode very low in the water. In any running sea, the rafts were awash, making it difficult for men working on them to keep their footing and avoid being swept overboard. Captain Faucon noted on the report of his trip to Port Royal that, when being towed, the rafts tended to “bury” their noses in the swell, which added to the difficulty of maneuvering with them.9

At the front of each raft was a low wooden bulkhead intended to prevent water from washing over it while under way. Along each side were three heavy iron plates surrounding metal-lined holes through which iron grapples were lowered on chains to drag the bottom for mines or cables. Each grapple could be raised on its own but was also attached by a horizontal chain running to a hawse hole in the center of the raft, which could be used to raise or lower the grapples together.10

The Plan

The recapture of Charleston had become something of a fixation for the administration and the Navy Department, less for practical or strategic reasons than for the city’s symbolism as site of the violent spark that set off the war. Du Pont’s South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, with Charleston as the principal Confederate harbor in its oversight, had come under increasing pressure to see to its capture, and the Navy Department saw the new Passaic class of ironclads—larger and improved versions of Ericsson’s original—as the way to do it. Fox, who was arguably more influential in guiding naval operations and policy than either his boss, Navy Secretary Gideon Welles, or President Lincoln, invoked an apocalyptic vision of the fight between good and evil, writing to Du Pont that “the fall of Charleston is the Fall of Satan’s Kingdom.”11

Like Ericsson, Du Pont was skeptical of the effectiveness of the monitors in destroying or silencing the Confederate batteries, including Fort Sumter, that ringed Charleston Harbor. In particular, Du Pont was keenly aware that, despite the protection provided by their heavy armor, the monitors still only mounted two guns each. Welles and others imagined that taking Charleston was simply a matter of getting past the harbor forts, anchoring off the city, and demanding its surrender, much as Rear Admiral David Farragut had done at New Orleans a year before. But Du Pont recognized that the geography of Charleston was very different, and there was no getting past the batteries to a safe anchorage off the city; the forts could hammer his ships anchored off the city as easily as when they were in the approaches to the harbor. Du Pont concluded that the forts themselves had to be silenced, and that taking Charleston would require working in concert with a strong land force.12

But the Navy Department, driven by Welles’ complete confidence in the effectiveness of the new monitors, and backed by Fox’s determination to see the Stars and Stripes fly again over Charleston, would not be deterred. Newly commissioned Passaic-class monitors began arriving to join Du Pont’s squadron in January 1863, and were soon supplemented by the hulking USS New Ironsides, a somewhat more conventional design that featured 18 heavy guns mounted as broadside armament. By April, Du Pont had assembled a force of seven new monitors, plus New Ironsides and an experimental, shallow-draft ironclad, USS Keokuk, for his assault on Charleston.

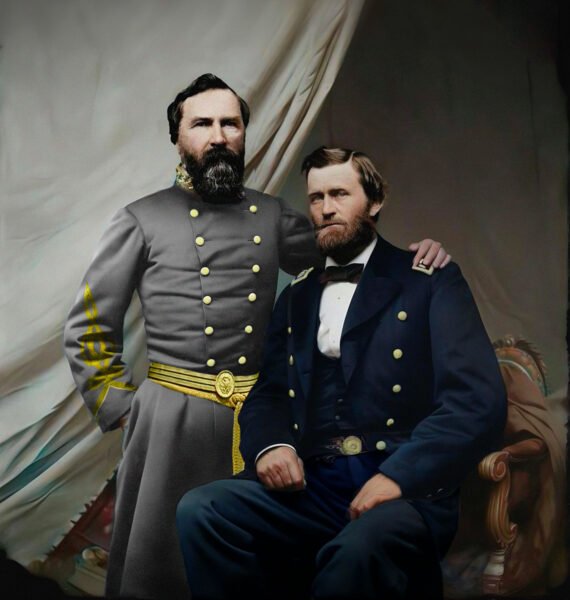

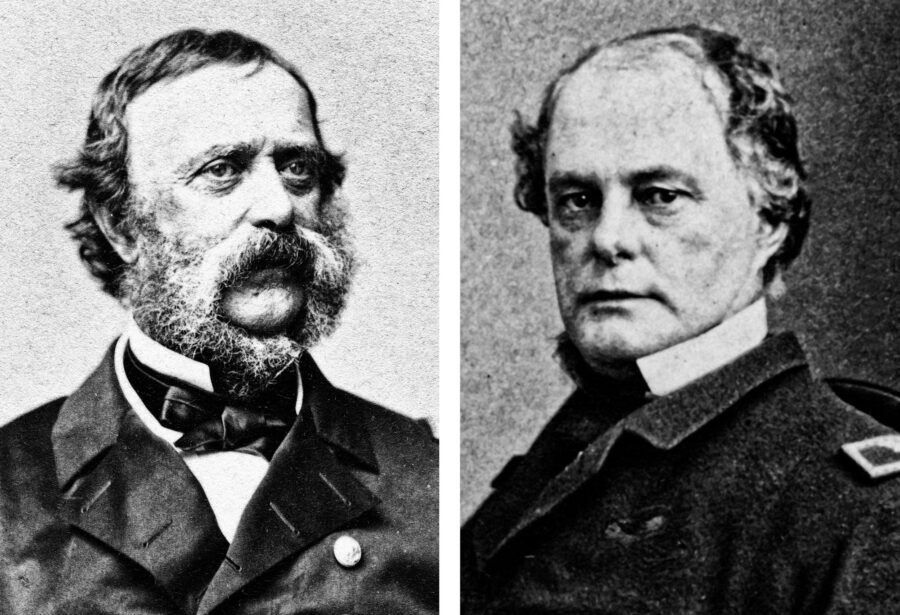

National Portrait Gallery (Du Pont); Naval History and Heritage Command

National Portrait Gallery (Du Pont); Naval History and Heritage CommandSamuel Du Pont (left) and John Rodgers

The simultaneous land attack on the forts never came about, but the Navy Department, eager to get on with the assault and having supreme confidence in the new technology represented by turreted monitors, pressed forward. And Lincoln was said to be losing patience with Du Pont, seeing his repeated requests for more resources, combined with an obvious hesitation to go on the attack, to be more than a little reminiscent of George McClellan, whom he had relieved of command of the Army of the Potomac a few months before.13 So as with many military operations throughout history, preparations for the ironclads’ attack on Charleston moved forward with their own momentum in early 1863, even without all the necessary components being in place, and against the better judgment of its commander.

With a squadron of the seven Passaic-class monitors in the lead, Du Pont’s attack got underway on the afternoon of April 7. The remaining example of Ericsson’s “Obstruction Remover” raft was fitted to the monitor Weehawken, though only after its commander, Captain John Rodgers, declined to attempt its use with the original torpedo attached, deeming it far too dangerous to his own and other vessels, given the way it impaired his ability to steer. (Rodgers was no stranger to dangerous naval operations, as he had brought Weehawken from Brooklyn to Charleston through the same storm that sank the original USS Monitor a few months before.)

Du Pont’s fleet had to contend not only with the forts and batteries that surrounded the entrance to Charleston, but also with the obstructions placed to prevent the passage of enemy ships. Of particular note were those across the narrowest part of the approach, from Fort Moultrie on the northern bank almost to Fort Sumter. It was this specific line of obstructions that Ericsson’s rafts were intended to breach, to allow the ironclads to get past Sumter, and perhaps all the way to Charleston itself. But the obstructions had changed. It was originally a line of pilings, heavy upright timbers driven into the bottom, standing like the pickets of an enormous fence. But the piles had not held up well to the tides and the Confederates tried alternate designs. By April 1863, the barrier consisted of what amounted to a loose open net, somewhat like an enormous table tennis net, consisting of three heavy rope cables, the upper cable secured to beer barrels to float at the surface to snare the paddlewheels of any steamer that tried to cross over it. Two more cables were suspended horizontally below the buoyed upper cable, and all were connected one above the other by lighter ropes.14

Du Pont and his commanders had only limited knowledge of the rope barrier obstruction or the harbor defenses in general. He already had a sense of foreboding about the success of any unsupported naval attack on Charleston, the defenses of which he had once described as “a porcupine’s hide and quills turned outside in.” But he had also failed to make extensive reconnaissance of the approaches to Charleston himself, instead relying on information provided by Confederate deserters and escaped slaves, whose testimony Du Pont may have been unwilling to trust fully.15

The failures in preparation were not only Du Pont’s. The seven monitors rushed to his squadron were so new that they and their armament—one 11-inch and one 15-inch smoothbore gun each—had never been tested against a masonry target like Sumter. The guns were enormous, but fired relatively light shells at low muzzle velocity. Nor did the naval officers know at what range the monitors’ armor would protect them from Confederate fire. Ericsson had guessed the monitors would be safe outside a range of 400 yards, but Rodgers and DuPont finally settled on a plan to fire on Sumter from a range of 1,250 yards, more than three times as far.16

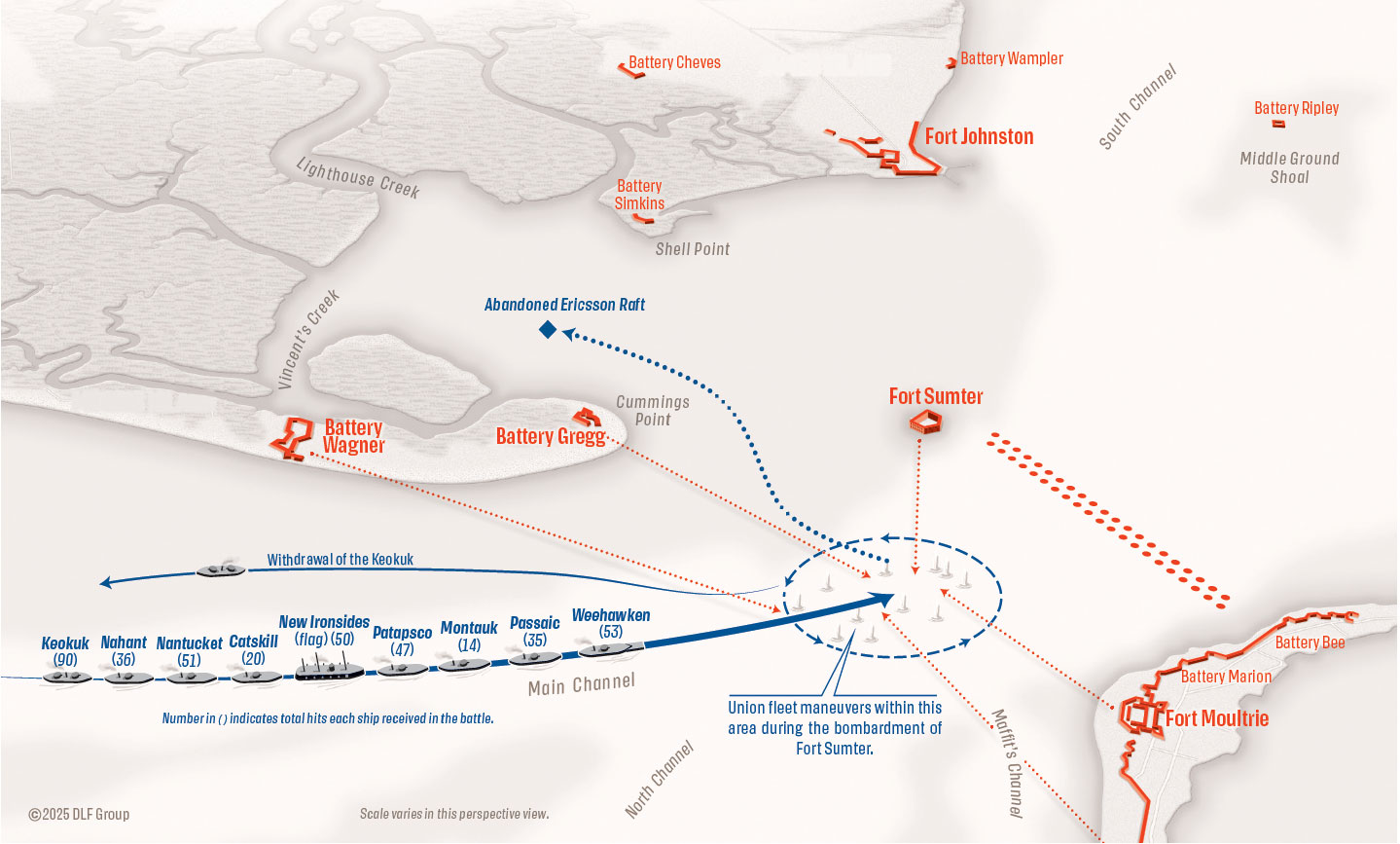

The First Battle of Charleston Harbor | In April 1863, Admiral Samuel Francis Du Pont led a Union naval assault on the Confederate defenses at Charleston. His attacking force, comprising nine ships—seven Passaic-class monitors (one of them, USS Weehawken, fitted with John Ericsson’s “Obstruction Remover” raft), the experimental, shallow-draft ironclad USS Keokuk, and the hulking flagship USS New Ironsides—was meant to run the guns of Confederate forts and break through the obstructions placed in the harbor intended to prevent the passage of just such enemy ships. Du Pont hoped to move his fleet past Fort Sumter and perhaps on to Charleston itself. In the end, his insufficient preparation, the limited range of the Passaic-class monitors’ guns, and the design failures of Ericsson’s raft (which Weehawken’s crew cut loose) worked against the fleet. After three hours of pummeling fire from Confederate guns (Keokuk alone had been hit 90 times and would sink the following morning), Du Pont called off the attack.

The Attack

The attack got underway on the afternoon of Tuesday, April 7. Rodgers led the advance in Weehawken, with the disarmed Ericsson raft affixed to its bow. Without the torpedo attached to blast a gap in the harbor obstructions, Weehawken’s role was to use the raft to clear a path for the following ironclads by sweeping the bottom using the grapnels hanging below the raft. The entire operation was delayed briefly when Weehawken’s own anchor became fouled by the raft’s grapnels, and Rodgers soon found Weehawken could make only about 3 knots (3.5 mph) through the water, further delaying the attack. Once underway, the heavy raft pounded Weehawken so severely that Rodgers gave up and had his crew cut it loose, choosing to fight without the protection against Confederate mines that the raft was supposed to provide his ship.17 The ironclads pounded the forts around the harbor, but with little effect, and failed to get past Sumter into the approaches to the city itself. Du Pont eventually recalled his ships late in the afternoon, three hours after the action began.

After withdrawing his ironclads, Du Pont convened a meeting of captains aboard New Ironsides. The ironclads had been badly pummeled. Keokuk had been hit 90 times, pierced at or below the waterline 19 times, and was barely still afloat.18 (It would sink the next morning.) Weehawken, which had led Du Pont’s squadron into action with the one remaining Ericsson raft, had been hit 53 times, knocking off armor plates and exposing the timber backing beneath. And so it went, down the line of monitors, Passaic, Montauk, Patapsco, Catskill, Nantucket, and Nahant. All of them had sustained damage, several of them seriously enough that they would be unfit to return to action for days or weeks. The slow-firing monitors had managed to get off a combined 154 rounds during the three-hour action; the Confederates had fired over 2,200 rounds, scoring nearly 400 hits on the ironclads. After thinking on it overnight, Du Pont sent word to his captains early on the morning of April 8 that the attack would not be renewed. Du Pont’s senior officers concurred with his decision.19

Assigning Blame

The First Battle of Charleston Harbor, as the April 7, 1863, action came to be known, proved to be an abortive and costly failure for Du Pont’s squadron, and ultimately led to his removal from command. While Du Pont had been skeptical of the chances of success, particularly in the absence of a simultaneous attack on the forts from land, the onus of failure weighed on his shoulders, more than on Fox or Welles, both of whom had been convinced of its success and leaned heavily on Du Pont to carry it out. Welles was angrier about the failure of the attack than was the president, but Du Pont might still have retained his command of the squadron were it not for an article on the attack written by Charles C. Fulton, the U.S. postmaster at Port Royal, and published in the Baltimore American eight days after the action. Fulton’s article excoriated Du Pont’s leadership, and particularly his decision to withdraw and not resume the attack the next day, insisting that Du Pont’s monitors were essentially undamaged and that their fire had brought Sumter almost to the point of capitulation, neither of which was true. The article also impugned the execution of the plan by the monitors which, Fulton argued, could have succeeded if they had just pressed the attack harder.

Naval History and Heritage Command

Naval History and Heritage CommandAlban Stimers

It turned out that while Fulton had witnessed the action from a distance aboard the transport Ericsson, his principal source of information was Ericsson’s colleague Alban Stimers, who was determined to defend both the effectiveness of the Passaic-class monitors that he had helped develop and the raft used in the attack, for which he had been the Navy Department’s representative on scene—and to deflect blame for the attack’s failure away from the monitors and the raft, and onto Du Pont and his officers.

Du Pont and his officers were naturally incensed. The commanders of the monitors, including Rodgers, replied with a long memo to Secretary Welles, defending their actions vigorously and refuting Fulton’s (and Stimers’) claims point-by-point. They particularly contested the Baltimore American story’s assertions about the supposed effectiveness of Ericsson’s raft. The captains wrote:

These torpedo rafts had merely a theoretical reputation for removing obstacles, never having been tried at the North or elsewhere, except in blowing up water, and certainly being a source of great danger to our own vessels in fouling each other—a matter very likely to occur, taking into consideration the tide, the Shoal water, and the imperfect steering qualities of the vessels, and which actually did occur on several occasions….

It is said that these rafts, sent down to be attached to the bows of our vessels, were refused without trial and from mere naval prejudice or personal feeling. This is no truer than the other statements. Although plain to us that vessels which, at the best, are very unmanageable from losing steerage way the very instant that the propeller stops, and from scarcely being able to go more than 4 knots, and some of them not even that, would be made more so by these great projections forward, which could never have been prepared for in the original plans of the ironclads. Still, one of them was tried in our presence, and under favorable circumstances for steering, as the torpedoes were not attached. We were soon, however, convinced that our unfavorable impressions with regard to them were correct, and that in the rapid currents and narrow channels of Charleston Harbor we would most likely get our vessels ashore, clogged with such a hindrance to their turning quickly.20

Du Pont replied to the Baltimore American story as well with a long, rambling report to Welles, but by then both Welles and Fox had decided Du Pont was not the man the navy needed to take Charleston.21 Du Pont knew he had been outmaneuvered by Stimers, and was relieved of his command at his own request in early July 1863. Charleston would remain in Confederate hands for almost two more years, until P.G.T. Beauregard’s troops evacuated the city ahead of William T. Sherman’s advancing army. Du Pont’s skepticism over the success of a solely naval attack on Charleston had been vindicated, although he would not long survive the war, dying in Philadelphia in June 1865.

Even after the debacle of April 7, Ericsson and others persisted in pressuring the navy to refine and use his rafts against harbor obstructions. The South Atlantic Blockading Squadron continued testing them through the summer and fall of 1863, under the tenure of Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren, but the difficultly in maneuvering the monitors with the rafts attached and the temperamental complexity of the explosives and fusing were obstacles that outweighed their practical use, and they never saw further action.22

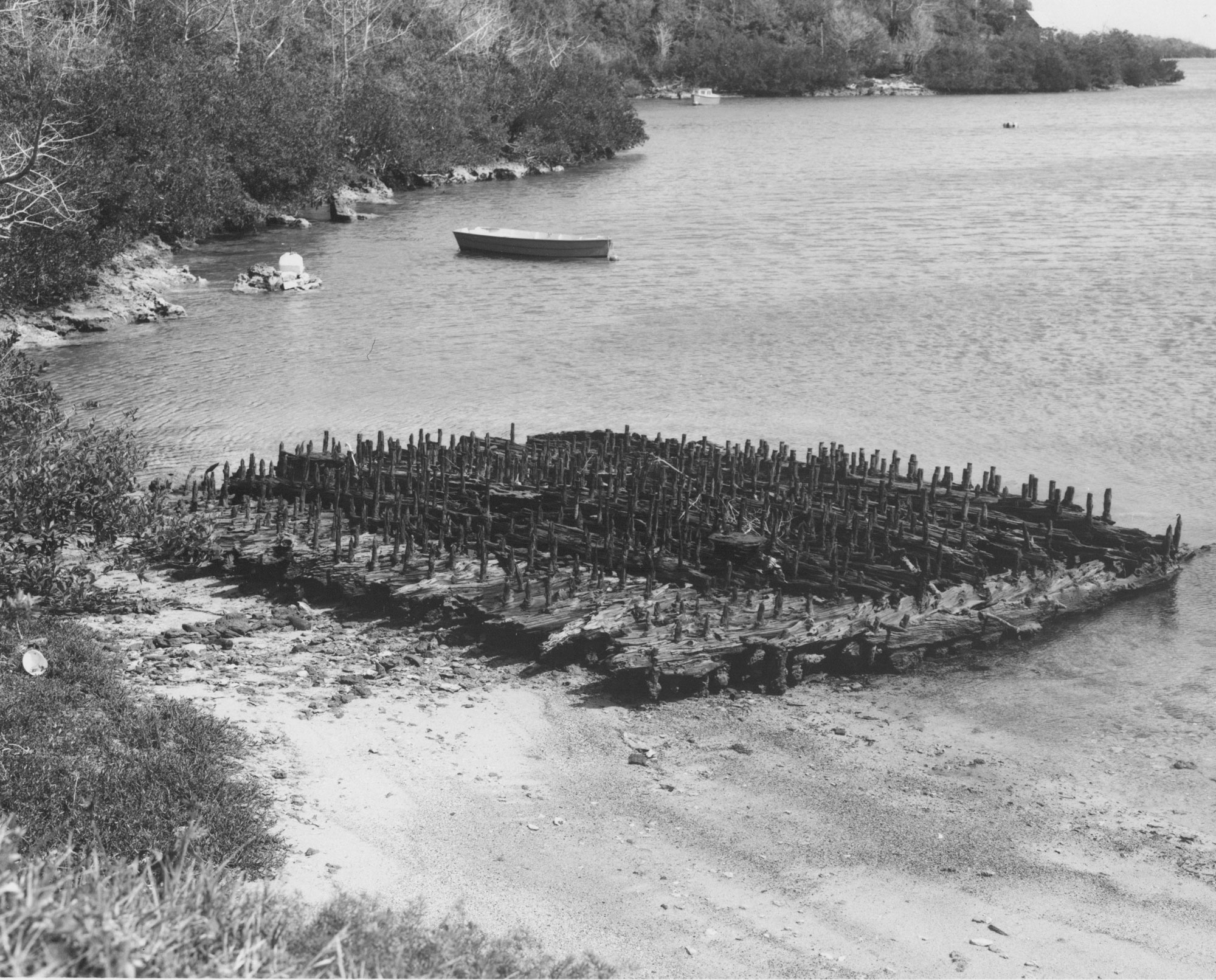

National Museum of Bermuda

National Museum of BermudaAfter the failure of Ericsson’s obstruction-clearing raft in the attack on Charleston, the invention never again saw action. In 1868, one of the original four rafts (pictured above in 1965) washed ashore in Bermuda, where it was left to rot.

Rediscovery

It was January 1872 and Faucon, now retired, had arrived in Bermuda aboard the mail steamer Alpha. A resident had implored Faucon to follow him to Dolly’s Bay, several miles north of the capital, Hamilton, on the north side of St. David’s Island, to offer his opinion on a mystery. Four years before, in 1868, a heavy timber structure had been found adrift near the island. It was towed into Dolly’s Bay with the intent of dismantling it for its timber (always a scarce commodity in Bermuda), but the would-be salvors eventually gave up the effort due to the mass of iron reinforcing bars running through it. It was left to rot quietly, although it remained a local curiosity.23

Faucon recognized the structure immediately, of course; it was one of the Ericsson rafts that had come adrift during the tow down from New York. Faucon even recognized the government property number still affixed to it. The old seaman was reportedly overheard saying, to no one in particular, “never did I expect to be shipmates with that again.”24

Possibly the most remarkable aspect to the story of Ericsson’s rafts is that of the four that set out for Charleston, three survive today. In addition to the raft that came ashore in Bermuda in 1868, there are two others: the raft that was abandoned and ultimately drifted ashore in one of the inlets on the back side of Morris Island, and what is very likely a third, which was discovered on Mustang Island, Texas, near Corpus Christi.

The raft near Morris Island was found immediately by the Confederates, and detailed in a report on the April 7 action by William H. Echols, a major of the Confederate Engineering Department. It was Echols who assigned the rafts the name “devils.” The Confederate major described the abandoned raft in detail, and included a drawing of it that matches, almost line-for-line, Ericsson’s plan. Echols also correctly guessed at Captain Rodgers’ difficulty in managing the raft while underway:

The “devil” floated ashore on Morris Island; the cables by which it was attached to the turret’s [i.e., monitor’s] bow were cut away. It is probable that the “devil” becoming unmanageable, was the cause of the turret retiring early from the action, [the raft] being a massive structure, consisting of two layers of white-pine timbers, 18 inches square, strongly bolted together; a reentering angle 20 feet deep, to receive the bow of the vessel, 60 feet long, 27 feet wide….”25

The Mustang Island raft was found after Hurricane Allen made landfall on the Texas coast in August 1980, with winds of at least 129 mph and a storm surge as high as 12 feet. The dramatic beach erosion that resulted exposed unusual disarticulated wreckage, broken into three principal sections spread over an area of about 35 feet by 38 feet. The wreckage was distinctive, very closely matching the heavily reinforced timbers of the Dolly’s Bay raft. The object was formally examined in the fall of 1985 by nautical archaeologists from the Corpus Christi Museum, the Texas Historical Commission, and the Institute of Nautical Archaeology at Texas A&M University, assisted by local volunteers. Although the Mustang Island object was in very poor condition, the team concluded that without doubt it was a Civil War–era raft designed to survive contact with naval mines. There was some initial speculation that it might date from a small action undertaken by the Union navy against Corpus Christi in 1862, but there was no clear evidence of similar rafts being used there, and, in fact, rafts of that type do not appear in official reports until discussion of the Ericsson rafts used at Charleston in April 1863. The team concluded that the available evidence clearly suggested that the Mustang Island object was one of the latter rafts, washed ashore on the Texas coast and buried in the dunes for decades before being discovered after Hurricane Allen in 1980.

Based on recognizable features of the structure, the team assessed that the Mustang Island raft’s remains are upside-down, and that it was likely flipped over while being propelled well up into the dunes by some earlier, long-forgotten storm. Although the presumed path the drifting raft must have taken to eventually land on Mustang Island might seem implausible, the team pointed out that Sargassum (seaweed) originating in the mid-Atlantic routinely washes ashore all along the Texas coast, sometimes in such great volume that it becomes an ugly, smelly nuisance to beachgoers. It is thus not at all unlikely that given time, one of the rafts lost off Cape Hatteras might eventually find its way to Texas.26 As of late 2023, the raft on Mustang Island has been reclaimed by the dunes, and there are no remains visible on the surface.

All three surviving Ericsson rafts—in South Carolina, Bermuda, and Texas—are known and recorded by local historical/archaeological groups, and are protected by local preservation laws and regulation. They should not be disturbed.

Andrew W. Hall is a researcher who writes and speaks regularly on naval and maritime history topics. He is a volunteer marine archaeology steward with the Texas Historical Commission, assisting with the investigation of historic shipwrecks in Texas waters. Thomas J. Oertling holds a bachelor’s degree in anthropology from Tulane University and a master’s degree in Nautical Archaeology from Texas A&M University. He has 35 years’ experience as a nautical archaeologist and 19 years’ experience teaching at Texas A&M University at Galveston. He has worked on the excavation of Denbigh, a Confederate blockade runner lost at Galveston in the closing days of the Civil War, and has participated on projects in the U.S., the Caribbean, Canada, Spain, and Turkey.

Notes

Acknowledgments: The authors extend their sincere thanks to the professional museum staff and archaeologists who provided information and material for inclusion in this article, including Ms. Jane Downing, Registrar of the National Museum of Bermuda; maritime archaeologist Dr. Justin Parkoff; and Mr. James D. Spirek, State Underwater Archaeologist with the Maritime Research Division, South Carolina Institute for Archaeology and Anthropology, University of South Carolina.

1. Report of Rear-Admiral Du Pont, U.S. Navy, Transmitting Report of the Commanding Officer of the Steamer ERICSSON Regarding the Passage of that Vessel from Hampton Roads,” in United States Naval War Records Office, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion 30 vols. (Washington, 1894–1922), Series I, Vol. 13, 669–670 (hereafter cited as ORN).

2. ORN, Series I, Vol. 13, 669.

3. Ibid., 670.

4. Ibid., 670.

5. Richard Henry Dana, Two Years Before the Mast (New York, 1899), 177, 204.

6. William Conant Church, The Life of John Ericsson (London, 1892), II: 45–46.

7. ORN, Series I, Vol. 14, 89.

8. Church, The Life of John Ericsson, 49–50.

9. ORN, Series I, Vol. 13, 669–670.

10. ORN, Series I, Vol. 14, 89, 93.

11. Quoted in Craig L. Symonds, Lincoln and His Admirals: Abraham Lincoln, the U.S. Navy, and the Civil War (New York, 2008), 200.

12. Ibid., 202–203.

13. Ibid., 204, 208.

14. Robert M. Browning Jr., Success was All that was Expected: The South Atlantic Blockading Squadron During the Civil War (Washington, 2002), 156–158.

15. Ibid., 158.

16. Ibid., 170.

17. James D. Spirek, The Archeology of Civil War Naval Operations at Charleston Harbor, South Carolina, 1861-1865 (Columbia, 2012), 106.

18. Browning, Success, 178–179.

19. Ibid., 174-80

20. ORN, Series I, Vol. 14, 46–47.

21. Symonds, Lincoln and His Admirals, 215–218.

22. ORN, Series I, Vol. 15, 103; Spirek, Civil War Naval Operations, 121

23. Eugene B. Canfield, “Ericsson’s Torpedo Raft Still Survives,” Naval History, vol 13, no. 4 (August 2000): 52; Donald R. Gardner, “The Civil-War Raft in Bermuda,” Bermuda Historical Quarterly, vol. XXII, no. 3 (Autumn 1965): 77; Tom Oertling, “Civil War Raft: A Civil War DEVIL on Mustang Island, Texas,” Seaways (January/February 1991): 34.

24. Gardner, “Civil-War Raft,” 77; Oertling, Seaways, 34.

25. ORN, Series I. Vol. 14, 89.

26. Herman A. Smith, J. Barto Arnold III, and Tom Oertling, “Investigation of a Civil War anti-torpedo raft on Mustang Island, Texas,” International Journal of Nautical Archaeology and Underwater Exploration 16.2 (1987): 150–151.

Related topics: naval warfare, technology