National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian InstitutionThe showman and regular purveyor of hoaxes P.T. Barnum (pictured opposite with Charles Sherwood Stratton, aka General Tom Thumb, in 1850) came clean about his many deceptive “enterprises” in his 1855 autobiography. “I prefer frankly to ‘acknowledge the corn’ wherever I have had a hand in plucking it,” Barnum wrote.

Acknowledge the corn | idiom | { common } An expression of recent origin, which has not become very common. It means to confess or acknowledge a charge or imputation.1

A uniquely American expression popular in the mid-19th century, acknowledge the corn, traces its roots to political discourse in the age of President Andrew Jackson (1829–1837). In 1828, a heated debate occurred on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives between congressmen Andrew Stewart from Pennsylvania and Charles A. Wickliffe from Kentucky. “Ohio, Kentucky, and Indiana,” claimed Stewart, “sent their haystacks, cornfields and fodder to New York and Philadelphia for sale.” Wickliffe, an independent who often identified with the Whig Party, called Stewart to order and countered his claim. To which Stewart retorted, “Well, what makes your horses and mules, cattle and hogs? You feed one hundred dollars’ worth of hay to a horse. You just animate and get on top of your haystack and ride it off to market.” Having lost the argument, Wickliffe admitted to the lesser offense: “Mr. Speaker, I acknowledge the corn.”2

The truth of this account, which first appeared in an 1872 publication and was frequently republished in late 19th-century newspapers and magazines, is suspect at best.3 The phrase acknowledge the corn never appears in the Register of Debates in Congress for 1828 or 1829 nor did any of the major newspapers in Boston, New York, or Washington, D.C., use the phrase in any account of the 1820s tariff debates.4 Another version of the congressmen’s argument appeared in Stewart’s posthumously published The American System (1872). Under the subhead “The Origin of the Common Saying ‘I Acknowledge the Corn,’” Stewart again related the 1828 tariff debates and the back-and-forth with Wickliffe. He wrote that the phrase was first uttered by Wickliffe and soon thereafter picked up by newspapers.5 Also published in 1872, Maximilian Schele De Vere’s Americanisms: The English of the New World offered two potential origin stories for the phrase, one of which referenced the 1828 debate. In defining the term, Schele De Vere wrote, “Among the many slang terms derived from the beautiful and valuable plant, none is probably more frequently heard than that of acknowledging the corn, which is a more prosy variation of acknowledging the soft impeachment. The former means a confession of having been mistaken or outwitted, as the occasion may warrant.”6

The phrase having entered the lexicon over the 1840s and 1850s, newspapers across the country called for editors and journalists to acknowledge the corn after reporting falsehoods in print. After incorrectly reporting the distance between two Pennsylvania towns, the Mountain Sentinel ordered the editors of its rival, the Johnstown News, to “Come out, then, and acknowledge the corn like men, and do not … destroy your ideas of truth altogether.”7 Other authors used the phrase in short stories, magazines, and books. Well known for both showmanship and fraud, P.T. Barnum made a fortune crafting, promoting, and selling hoaxes. He exhibited the “Feejee Mermaid,” concocted from a monkey’s torso and a fish’s tail, in cities across the country.8 In his 1855 autobiography, Barnum wrote, “None of my enterprises, however, have been omitted, and though a portion of my ‘confessions’ may by some be considered injudicious, I prefer frankly to ‘acknowledge the corn’ wherever I have had a hand in plucking it.”9

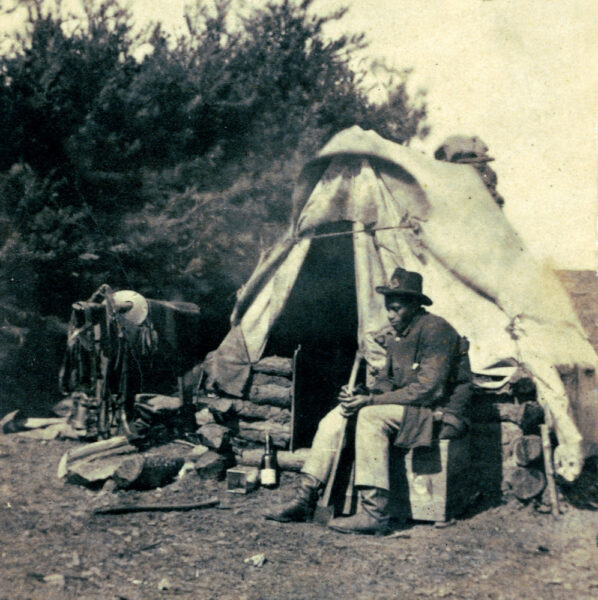

By 1861, Civil War soldiers understood the phrase and the personal honor required to admit wrongdoing. In camp, they played practical jokes on their comrades-in-arms. In 1885, Confederate artillerist William Miller Owen fondly recalled men’s wartime antics in camp. An unsuspecting and “credulous fellow” would be sent on “a wild goose chase to find a letter or package from home, or something imaginary said to be in the possession of ‘Bolivar Ward.’” That “mythical personage” never existed, of course, and after several hours someone would acknowledge the corn.10 While campaigning in Virginia, a Confederate urged his footsore and blistered comrades to confess their pride and acknowledge the corn after marching for five days in captured boots with thin soles.11

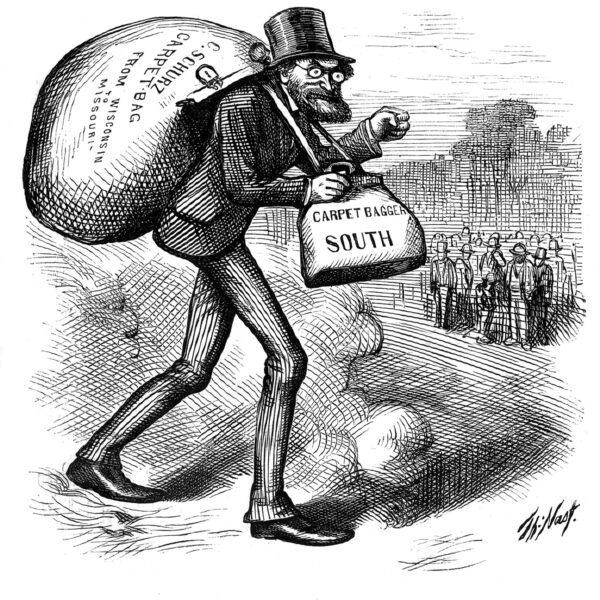

Politicians, including President Abraham Lincoln, were publicly called upon to acknowledge the corn. The New York Illustrated News and the Funniest of Phun, both edited by abolitionists and Radical Republican W. Jennings Demorest, often criticized the president for what they considered to be his conservative beliefs. Lincoln’s “Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction” issued on December 8, 1863, offered a full pardon to southerners who took an oath of loyalty and accepted the abolition of slavery—but it angered Republicans such as Demorest and cartoonist Frank Bellew. Condemning the lenient Reconstruction policy aimed at welcoming the rebel states back into the Union fold, Bellew published a political cartoon in the pages of the New York Illustrated News on April 2, 1864. In “Mr. Lincoln’s Great National Joke,” a naïve Lincoln scatters corn to scraggly Confederate chicks in a vain effort to make the “Rebels Acknowledge the Corn.” In the image’s foreground stands an eagle, protecting healthy Union chicks from an aggressive rooster, Confederate president Jefferson Davis.12

In other cases, the confessor was acknowledging a particular mistake: intoxication. Early uses of the phrase imply an overindulgence of corn liquor, which could be another origin story of acknowledging the corn. The first written usage of the phrase appeared in New Orleans, Louisiana, published in the The Picayune in 1839, and the article clearly referenced both a mistake and a saloon: “We ‘acknowledge the corn.’ Gowdey’s [in Nashville, Tennessee] is a most convenient and comfortable place. In soda, juleps and jewelry he has no equal…. But still we are in favor of the ‘gallon law;’ and we appeal to our friend of the [Natchez] Free Trader to say, if it should reduce the use of spirituous liquors to the standard of Tennessee, that it will prove one of the greatest blessings to the State of Mississippi. The people there do not drink one-tenth part of what they do in this state.”13 Then, in 1842, a man pleaded guilty before a Philadelphia judge, saying “Your honor, I confess the corn. I was royally drunk.”14 Inebriated Civil War soldiers too would have acknowledged the corn.

In 1907, Acme Brewing Co. in Macon, Georgia, playfully used the phrase to promote its American Queen Beer. According to the advertisement, Acme used only pure barley malt rather than a cheaper corn substitute, while other “brewers strictly avoid the all-important question of materials used in their beer. Some of them harp evasively upon the ‘purity’ of their product, just because they don’t want to acknowledge the corn!”15 The phrase gradually faded from usage until, in this century, when someone might acknowledge the corn, it is a reminder of days gone by.

Tracy L. Barnett is a doctoral candidate at the University of Georgia. Her dissertation analyzes the historical origins of America’s gun culture and its mutually constitutive relationship to white supremacist ideology. As the Digital Humanities Research Fellow, she worked as a research assistant for Private Voices, a website devoted to Civil War language.

Notes

1. John Russell Bartlett, Dictionary of Americanisms: A Glossary of Words and Phrases Usually Regarded as Peculiar to the United States (Boston, 1848), 1-2.

2. Emphasis added by author. Ballou’s Dollar Monthly Magazine, Vol. 72, No. 1 (July 1890), 87.

3. For example, see Darien Timber Gazette (Darien, GA), January 9, 1880.

4. U.S. Congress, Register of Debates in Congress, Vol. 4 (Washington, D.C., 1828); U.S. Congress, Register of Debates in Congress, Vol. 5 (Washington, D.C., 1830); Jeffrey Alan Hirshberg, “Going the Whole Hog to Acknowledge the Corn,” American Speech, Vol. 51, No. 1/2 (Spring–Summer, 1976), 102–108.

5. Andrew Stewart, The American System: Speeches on the tariff question, and on internal improvements, principally delivered in the House of Representatives of the United States (Philadelphia, 1872), 189–190.

6. Maximilian Schele De Vere, Americanisms: The English of the New World (New York, 1871), 48.

7. The Mountain Sentinel (Ebensburg, PA), December 20, 1849.

8. Kenneth S. Greenberg, “The Nose, the Lie, and the Duel in the Antebellum South,” The American Historical Review, Vol. 95, No. 1 (February 1990): 59–65.

9. P.T. Barnum, The Life of P.T. Barnum (London, 1855), v.

10. William Miller Owen, In Camp and Battle with the Washington Artillery of New Orleans: A Narrative of Events During the Late Civil War from Bull Run to Appomattox and Spanish Fort (Boston, 1885), 63.

11. R.T. Mockbee, “Why Sharpsburg was ‘A Drawn Battle,’” Confederate Veteran, Vol. 16 (1908): 165.

12. “Mr. Lincoln’s Great National Joke,” New York Illustrated News, April 2, 1864.

13. New Orleans Daily Picayune, April 5, 1839, as quoted in Hirshberg, “Going the Whole Hog to Acknowledge the Corn,” 107.

14. Spirit of the Times (Philadelphia), March 16, 1842, as quoted in Hirshberg, “Going the Whole Hog to Acknowledge the Corn,” 107.

15. The Brunswick News (Brunswick, GA), August 11, 1907.