Good morning! Our Women’s History Month celebration continues with this tribute to Mary Boykin Chesnut.

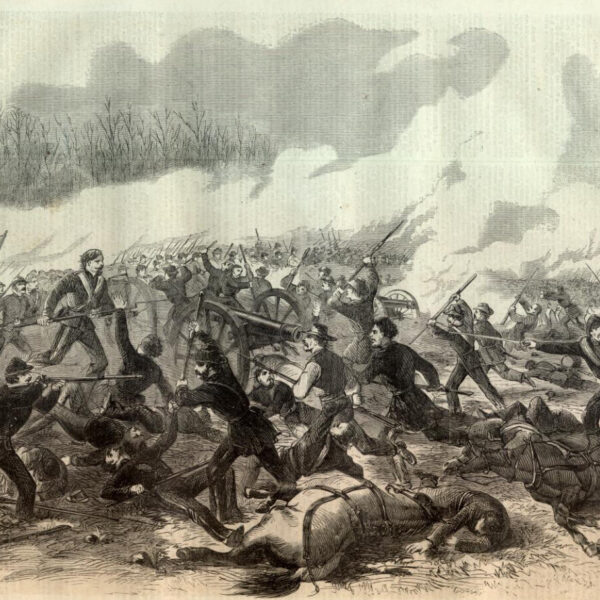

Mary Boykin Chesnut is perhaps the best known female diarist of the Civil War. Born in 1823 in Statesboro, South Carolina to Mary Boykin and Stephen Decatur Miller, a former U.S. Congressman, Senator, and Governor, Mary was educated at a French boarding school in Mississippi. She married James Chesnut, Jr. in April of 1840 and moved to Mulberry, his plantation. When James became a Senator on 1858, the couple travelled to Washington, D.C. and became good friends with Jefferson and Varina Davis. Proponents of secession, the Chesnuts were strong advocates for the war—James served in the Provisional Congress of the Confederate States of America, as an aide to President Jefferson Davis and General P.G.T. Beauregard and in the military, earning the rank of general while provided provisions to area hospitals, sewed shirts for soldiers, and wrote in her diary—and the two travelled together to Charleston, Montgomery, Columbia, and Richmond. After the war’s end, the Chesnuts returned to Mulberry and a pile of debt. Fortunately, they were able to rebuild their plantation and regain solvency before Mary died in 1886.

In the 1880s, prior to her death, May revised and edited her wartime diaries for publication. They have since been published under the titles of Mary Chesnut’s Civil War and A Diary From Dixie. Of the published diary, C Vann Woodward wrote:

The enduring value of the work, crude and unfinished as it is, lies in the life and reality with which it endows people and events and with which it evokes the chaos and complexity of a society at war. Her cast of characters includes slaves and brown half brothers, poor whites and sandhillers, overseers and drivers, common soldiers and solid yeomen, as well as the very top elite of state, military, and society that thronged her drawing room and saw her daily. She brings to life the historic crisis of her age with the literary techniques she had developed in the meantime, and again it is the rare fortune of the editor to have so much of the manuscript evidence of these experiments before him.

The following are a few excerpts are from her diary:

This war was undertaken by us to shake off the yoke of foreign invaders. So we consider our cause righteous. The Yankees, since the war has begun, have discovered it is to free the slaves that they are fighting—so their cause is noble. They also expect to make the war pay. Yankees do not undertake anything that does not pay. They think we belong to them. We have been good milk cows – milked by the tariff, or skimmed. We let them have all of our hard earnings. We bear the ban of slavery; they get the money. Cotton pays everybody who handles it, sells it, manufactures it,…—rarely pays the man who grows it. Second hand the Yankees received the wages of slavery. They grew rich. We grew poor. The receiver is as bad as the thief. That applies to us, too—for we received the savages they stole from Africa and brought to us in their slave-ships. As with the Egyptians, so it shall be with us: if they let us go, it must be across a Red Sea—but one made red by blood.

July 8, 1862

And

We fought to get rid of Yankees and Yankee rule. We had no use for Yankees down here and no pleasure in their company. We wanted to separate from them for aye. How different is their estimate of us. To keep the despised and iniquitous South within their borders, as part of their country, they are willing to enlist millions of men at home and abroad and to spend billions. And we know they do not love fighting per se—nor spending their money. They are perfectly willing to have three killed for our one. We hear they have all grown rich-shoddy—whatever that is. Genuine Yankees can make a fortune trading jack-knives.

April, 16, 1865

Source: Woodward, C. Vann, ed. Mary Chesnut’s Civil War. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981.

Image Credit: NPS.org.

Related topics: women