Library of Congress

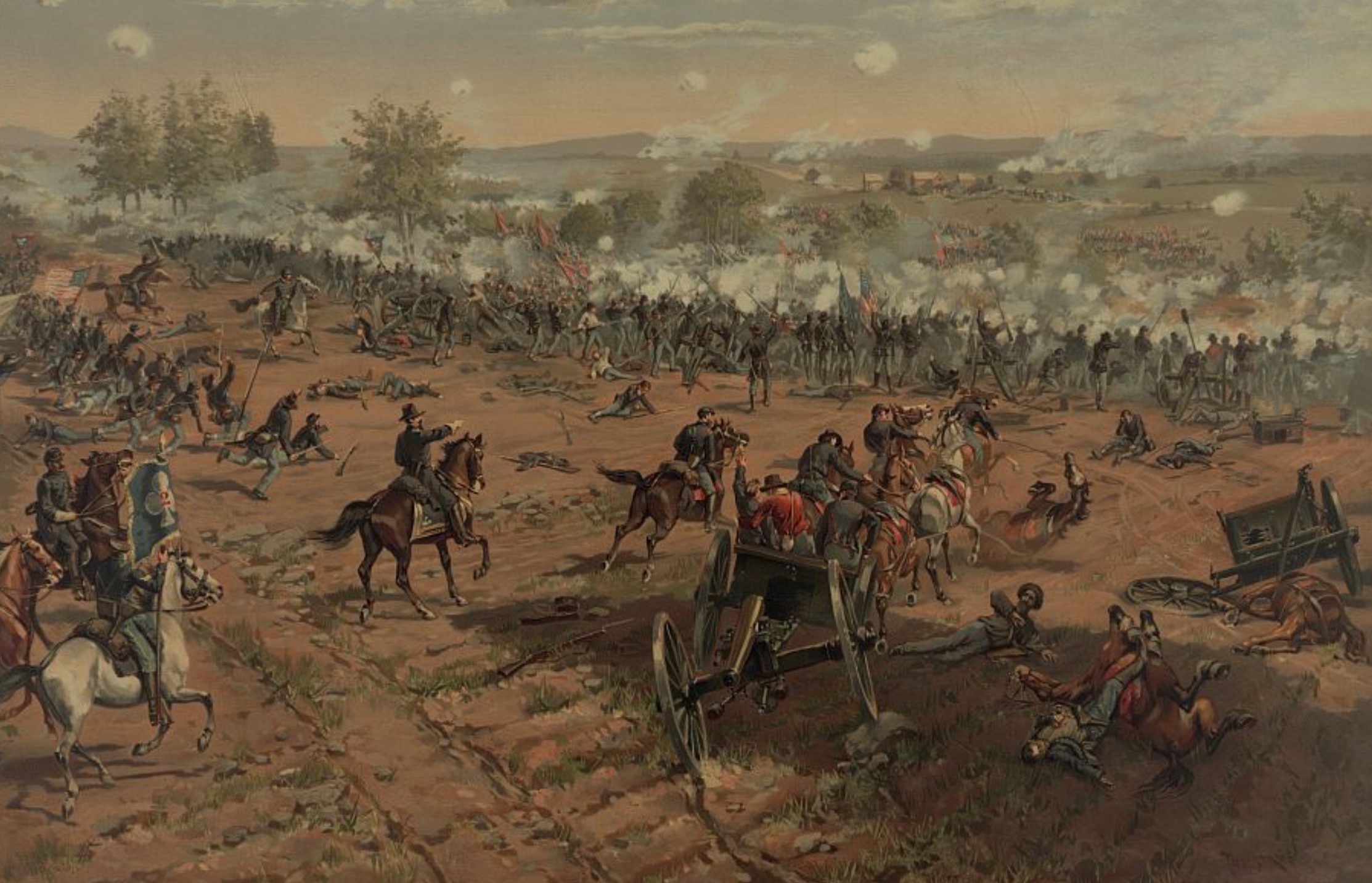

Library of CongressRichard Ewell’s Confederate soldiers attack Culp’s Hill during the Battle of Gettysburg in this painting by Edwin Forbes.

What do George McClellan’s decisions at Fair Oaks, Nathaniel Lyon’s tactics at Wilson’s Creek, Ulysses S. Grant’s failure to attack at Iuka, and Richard Ewell’s “demonstration” at Culp’s Hill have in common? The outcome of each engagement was directly affected by what the commanding officers could hear, and the military decisions in each situation were critically influenced by the presence of an acoustic shadow. This was especially true with the timing of attacks (Ewell, Lyon, and Grant) and the disposition of reinforcements (McClellan). At Iuka, for example, Grant planned a pincer movement to trap Sterling Price’s smaller force, attacking the town from both northwest and southwest to trap the Confederate Army of the West. The crucial timing for this maneuver was to be based on the sounds of the fighting, with the two divisions led by Edward Ord waiting until they heard the firing from William Rosencrans’ larger Army of the Mississippi. Instead, an acoustic shadow meant that Grant and Ord heard nothing of the fighting that was only a few miles away, and as a result they sat by, only learning of the engagement (and missed opportunity) many hours later.

Acoustic shadows can form in several ways on a battleground. Sound moves through the air as a mechanical wave. When a cannon fires, for example, the rapid expansion of hot gases in the chamber creates an extremely high-pressure center at the muzzle, the only place where the gases can escape from the barrel. This high-pressure zone compresses the adjacent air molecules, which then propagate the shock wave by compressing their neighboring molecules as well. This strong variation in pressure can be sensed by your eardrum, which vibrates when struck by the density change—your brain then converts these vibrations into a very loud sound.

As the sound of the boom travels away from the cannon it diminishes (attenuates). The rate of attenuation is dependent on your distance from the source and absorption of the waves by the environment. Acoustic shadows occur when sound waves should reach your ear, based on your distance from the source, but they don’t. There are several interacting factors that can intercept these waves. Sound can be absorbed by any dense material that is found between the sound source and the person listening, including vegetation, topography (hillslopes or mountains), and buildings. Because sound waves are moving through the air, the direction of the wind is also important—a cannon blast will be significantly louder to an observer who is downwind on a breezy day. Humid air also helps to absorb sound waves, which can also be bent and redirected away from the listener through wind shear and temperature inversions. Finally, air pollution in the form of particulate matter is an often-overlooked attenuator of sounds, especially with respect to what might be heard, or not heard, on a battlefield. When black powder burns, the abundant resulting smoke in the air can cause sound waves to be scattered and, to a lesser extent, absorbed. As a result, artillery will sound louder to a spectator on the first volley than on subsequent firings.

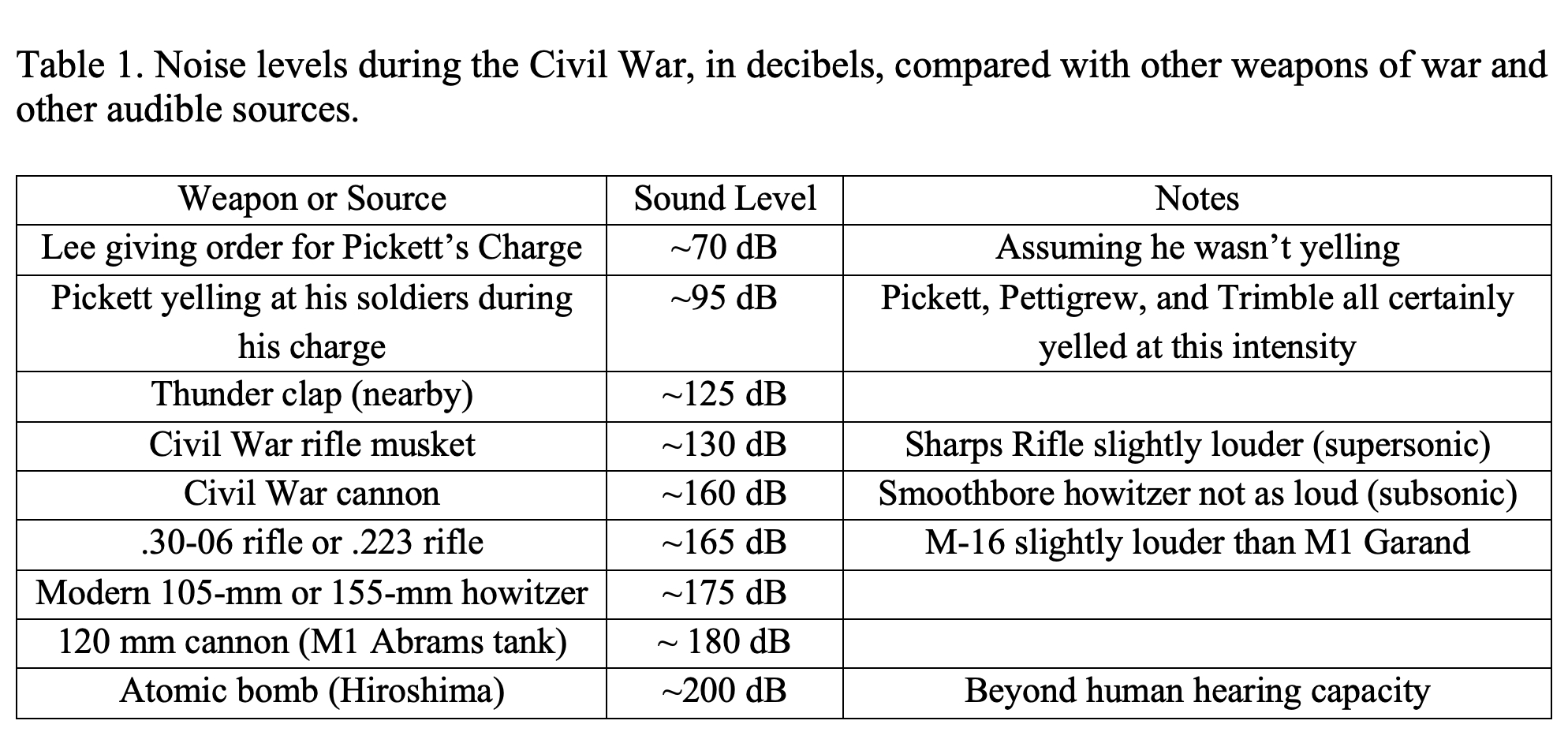

Returning to the source of the sounds, exactly how loud were the weapons of the Civil War, and how surprised should we be that in some cases they couldn’t be heard only a few miles away from the fighting? Table 1 summarizes the sound level of Civil War cannons and rifles, compared with weapons used during later conflicts (and some other sounds for comparison). Remember that the units of sound, decibels, are based on a logarithmic scale: An increase of 10 in decibel (dB) level is equivalent to a sound that is twice as loud and an increase of 20 decibels is the equivalent of a sound that is 100 times as intense. However, a human’s perception of loudness is not the same as the intensity of that sound; e.g., two cannons fired at the same time have double the intensity of a single gun—but do not sound twice as loud to a human.

When studying this chart, note that serious hearing loss can occur with long exposures to moderately loud sound at around 100 dB, or with acute exposure to extremely loud sounds over 140 dB. Beyond 160 dB, the rupturing of eardrums is a distinct possibility. Repeated exposure to Civil War rifles, or the sound of many rifles fired at once, may have led to hearing loss. Repeated exposure to Civil War cannons firing, or the sound of a battery of cannons fired at once, may have led to bleeding from the ears.

So how loud were Civil War battles? How deafening was a major assault like Pickett’s Charge, or the artillery bombardment that preceded that attack? And, finally, how far away would you expect to hear this cacophony? Two important factors weigh on how loud a fight is and how far away it can be heard. The first is obviously the intensity of the sound—a combination of the type of weapons and the number of weapons being fired simultaneously. The second is the frequency of the sound waves being created. Low frequency waves, like those of a booming cannon, will travel farther without being attenuated than will higher frequency waves like a rebel yell or the crack of a rifle.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressThure de Thulstrup’s depiction of the Union repulse of Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg.

For the overall intensity of an extremely loud battle event, like the artillery duel before Pickett’s Charge, the volume would be dependent on the number of cannons firing. As stated earlier, two cannons firing produces twice the sonic energy, but the perceived sound by humans is not twice as loud. The sound of multiple guns firing simultaneously only increases the sound by around 3 to 5 dB. You would need at least 10 cannons detonating at exactly the same time to double the perceived sound volume. If the Confederates had fired all of their artillery at Cemetery Ridge at exactly the same time (around 150 cannons), it would have been around four or five times louder than hearing a single cannon discharging. Of course, these cannon were spread along the length of Seminary Ridge, so observers would not have perceived the entirety of this intensity because of the range from each of the cannons and the variable time it took for the sound waves to reach them.

Famously, this tremendous sound was reportedly “clearly heard” halfway across the state in Pittsburgh, on the afternoon of July 3, 1863, but not 10 miles away in nearby communities—the result of an acoustic shadow. The Battle of Gettysburg was also reportedly influenced by an acoustic shadow on the second day of the fighting, when Ewell was ordered to coordinate his attack on the right of the Federal line at Culp’s Hill with the sound of Longstreet’s artillery fusillade against the Union left. This timing and coordination was undone by Ewell’s delay in issuing the order to attack, after he apparently didn’t hear the sound of Longstreet’s guns only 2 or 3 miles away. This delay was crucial, as it allowed time for Federal forces to swing reinforcements to the left and right as needed during the disjointed attacks.

How likely is it that Ewell couldn’t hear the 40 or so guns that Longstreet was employing to soften up the Federal position in and around the Peach Orchard? Several factors might have led to an acoustic shadow at his position north of Culp’s Hill, including the wooded and rocky crest itself. The primary direction of winds in this portion of southcentral Pennsylvania is from the west-northwest (~190°), while the direct line of sound from the center of Longstreet’s artillery to Ewell’s headquarters on Hanover Street was north-northeast (~20°). In other words, the wind was generally blowing perpendicularly to the direct line of sound from the guns to Ewell’s ear.

Scott Hippensteel

Scott HippensteelEarly morning on Little Round Top looking directly north, across the position the sound would have traveled between Longstreet’s guns and Ewell’s headquarters. The numerous sound baffling obstacles are highlighted in the mist, including ridges and forests.

There were also multiple ridges between the artillery position and Ewell’s, including several groves of trees. Houck’s Ridge, Little Round Top, Cemetery Hill, and Culp’s Hill are all found between the sound and the listener, and all are capable of reflecting sound (hard rock) or absorbing it (earth and vegetation). Note too that Longstreet’s artillery support for his assault didn’t start until around 3:30 p.m., the warmest part of the day—which means sound waves would have been reflected upward and away from the hot ground into the atmosphere. Had the assault started much earlier in the day, or a few hours later, the sound would have traveled much farther. All this indicates that Ewell and his staff may certainly have been in an acoustic shadow.

As for the sound of the larger cannonade that occurred July 3 being heard in Pittsburgh, I am skeptical. The cannon exchange prior to Pickett’s Charge was certainly significantly louder than the one during Longstreet’s July 2 assault, but the Iron City wasn’t just a few miles away from Gettysburg, it was also 160 miles directly upwind. And there aren’t just a few ridges and trees along the route, there is an entire wooded mountain range that is oriented perpendicular to the direction of the travel of the sound. When the atomic bombs were dropped at the end of World War II—two events louder than the artillery at Gettysburg—reports of the sound being heard beyond about 50 or 60 miles are scarce.

On a smoke-filled battlefield, or one with limited visibility because of terrain or forest cover, sound becomes an even more important tool for determining the location and actions of the enemy. This can be unfortunate as sound waves behave in a peculiar manner when traversing battlefields. Acoustic shadows were detrimental for McClellan at Fair Oaks, where he misjudged the strength and location of the Confederate forces. At Iuka, Grant never used half his army for lack of an auditory signal to attack. A commanding officer never wants to be blind on a battlefield, but being deaf can be worse. The quiet on the battlefield, even if not in the form of an acoustic shadow, could be even more harmful to the morale of individual soldiers. William C. Kent, a member of Berdan’s Sharpshooters, described the auditory sensations of combat after fighting at the Seven Days battles: “[The enemy was] delivering their fire in crashes, lengthening into long rolls, above which one could hear the yells of the rebels and the cheers of our men, and every little while, would come a silence far more awful than any noise, when nothing could be heard, but the shrieks and groans of the wounded.” Too much sound on a battlefield can be debilitating, and too little can be deceptive, but for the soldiers holding the muskets, the temporary diminishment of noise may allow a brief and horrifying window into the reality of what was occurring on the smoke-blanketed battlefield all around them.

Scott Hippensteel is professor of Earth sciences at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, where he focuses on coastal geology, geoarchaeology, and environmental micropaleontology. He has written four books about using science to illuminate military history: Sand, Science, and the Civil War: Sedimentary Geology and Combat (University of Georgia Press, 2023), Myths of the Civil War: The Fact, Fiction, and Science behind the Civil War’s Most-Told Stories (Rowman & Littlefield, 2021), and Rocks and Rifles: The Influence of Geology on Combat and Tactics during the American Civil War (Springer Nature, 2018). His latest book, Civil War Photo Forensics: Investigating Battlefield Photographs through a Critical Lens, is forthcoming from the University of Tennessee Press.

Notes

1. The attenuation of sound waves (or any point source emitting energy) is represented by the inverse square law: as the waves travel from the muzzle of the cannon outward, they are covering a larger and larger spherical area. The sound reaching your ears will be proportional to the inverse of the distance (sound (intensity) = 1/(distance2). If you are standing 10 meters away from a Napoleon when it is fired, the sound is literally deafening. For a soldier standing 20 meters away (a doubling of the distance), they will only hear 1/4 as much sound (intensity = 1/(22) = ¼; still a really loud boom). At 30 meters away, the sound diminishes to 1/9 as much (intensity = 1/(32) = 1/9; still very loud but perhaps not deafening). If you are observing from 100 meters away, the sound will be 1/100 as great as standing near the cannon, but you will still need ear protection from the loud rumble.

2. Sound waves bend toward areas with lower wind speeds (refraction), so that faster winds above will bend waves toward the ground. Wind shear, with respect to acoustic shadows, is most important when you have variable wind speeds at different elevations. Temperature inversions can also refract sound waves. When the sun goes down, the surface of the planet cools more quickly than the air above. The sound from a cannon will move into the atmosphere in all directions and when it reaches the higher, warmer air, it may be bent back toward the cooler ground at a longer distance away from the blast.

3. A rifle-musket produces a “crack” when fired that sounds like a loud firecracker; a cannon of the era produced a much lower, deeper “boom” and rumble. The higher frequency of the rifle shot (~1,000 – 2,000 Hz) will attenuate more quickly than the lower frequency cannon blast (~200 Hz). As a result, artillery can be heard much farther away than can an infantry firefight.

4. The cannon muzzles will all need to be the same distance from the listener for this to occur, otherwise the sound waves will arrive at different times, decreasing the maximum energy. This doubling in volume could easily cross the threshold into permanent deafness for nearby observers.

5. Charles D. Ross, Acoustic Shadows in the Civil War, 136th Meeting of the Acoustic Society of America (Norfolk, VA, 1998), Paper 2aPAa1.

6. A line drawn between Fraser’s Battery (Pulaski Artillery) position on July 2 and Ewell’s headquarters almost exactly cuts across the famous Copse of Trees.

7. Ewell and his staff were also active participants in the large battle from the day before, so they might also have been listening with ears that were still ringing.

8. Perhaps the citizens of Pittsburgh heard the sounds of a very big late-afternoon thunderstorm in Altoona or another nearby region to the east.

9. The sound from Hiroshima would have carried farther than Nagasaki, because the latter Japanese city is located in a region with a great deal of relief. The Trinity Test detonation of 1945 was heard 60 miles away in Alamogordo, New Mexico, but this town is directly downwind and the sound waves would have been moving across a landscape made of white sand with little vegetation.

10. This quote is from a letter from Kent to his parents on July 28, 1862, as taken from Earl J. Hess, The Union Soldier in Battle: Enduring the Ordeal of Combat (Lawrence, 1997), 18.