Gettysburg Foundation

Gettysburg FoundationThis detail from Paul Philippoteaux’s Battle of Gettysburg Cyclorama painting depicts close-quarters combat during the height of Pickett’s Charge. The ferocity of that engagement changed the soldiers who fought in it, including Union officer Henry Abbott and Confederate officer Henry Owen.

In June, I had the privilege of participating in the 2025 Civil War Institute Summer Conference at Gettysburg College. The experience was bittersweet, in that it was the first seminar after the death of a dear friend, and the CWI’s director, the brilliant and beloved historian Peter Carmichael.

My CWI session, presented with my colleague Andy Lang of Mississippi State University, was entitled “Why They Fought, How They Fought,” and was focused on how soldiers at Gettysburg thought about the war and experienced the fighting, with a particular emphasis on the final day of the battle. Preparation for the session and experiencing both the classroom portion and the battlefield components stirred my thinking on wartime decision-making and its consequences.

General Robert E. Lee’s decision to execute what has gone down in history as Pickett’s Charge, but perhaps more properly ought to be called Longstreet’s Assault or the Pickett-Pettigrew-Trimble Charge, was hotly debated from the moment it failed to dislodge the Union Army of the Potomac from Cemetery Ridge on the afternoon of July 3, 1863. Rather than relitigate the events that led to Lee’s decision, it would be useful to reflect on the concept of “consequences”; namely, how seemingly straightforward military decisions (to attack or not; when, where, and how) can have life-altering consequences for participants and survivors. The experiences of two officers who fought in Pickett’s Charge, one Union, the other Confederate, offer insights at the most intimate level.

By the summer of 1863, the hearts of both armies consisted of experienced volunteers and officers learned in the art of soldiering. While holding on to their citizen-soldier identities, the majority of men in the ranks of the Army of the Potomac and the Army of Northern Virginia were no longer novices. They were different people from the callow recruits of 1861; they knew a good deal about fighting and dying and the hardships of war. They knew very well they were not indestructible.

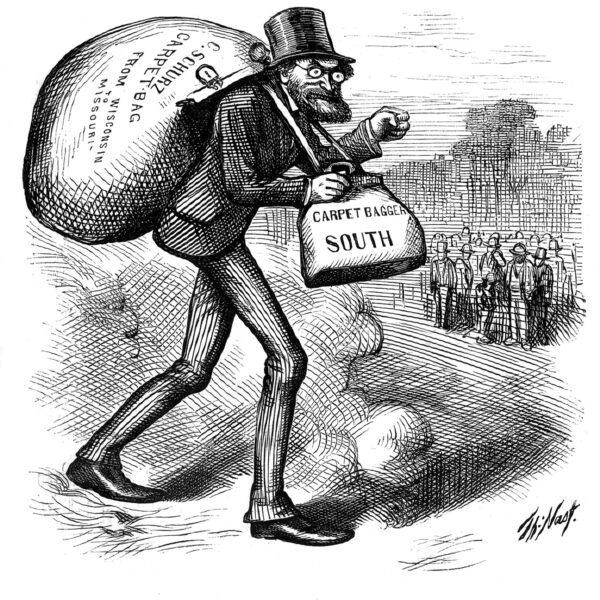

USAHEC

USAHECHenry Livermore Abbott

Harvard-educated Captain Henry Livermore Abbott, at 21 a company commander in the 20th Massachusetts Infantry, described the consequences of Pickett’s Charge in searing terms. “Every battle grows worse,” Abbott wrote to his father just days afterward, “and this corps lost 45 percent at Gettysburg….” Abbott understood death or injury was always a possibility, but he also knew he had to swallow his emotions and, when decisions came down from on high, order his men quite possibly to their deaths. Accepting this morbid reality took its toll on young men like Abbott. “It makes me sad to look on this gallant regiment which I am instructing and disciplining for slaughter,” he wrote, “to think that probably 250 or 300 of the 400 who go in, will get bowled out.”1 Abbott had lost too many friends by that summer, including two of his closest: Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., out of action with a serious wound, and Henry Ropes, killed at Gettysburg.

Abbott’s regiment, part of the Third Brigade, Second Division, II Corps of the Army of the Potomac, withstood the brunt of the Confederate assault on July 3, though at great cost. “[The Confederates] were obliged to come out of the woods & advance from a half to ¾ of a mile over an open field & in plain sight,” he reported. “A magnificent sight it was, too. Two brigades in two lines, their skirmishers driving in ours.” In fact, the attackers in Abbott’s vicinity consisted of Pickett’s division of three brigades, those of James Kemper, Richard Garnett, and Lewis Armistead. “The moment I saw them I knew we should give them Fredericksburg,” Abbott continued, referring to the way Lee’s Confederates had hammered advancing Union forces at the Battle of Fredericksburg seven months earlier. “So did every body. We let the regiment in front of us get within 100 feet of us, & then bowled them over like nine pins, picking out the colors first.” The effect of this close-range musketry was predictably devastating. “In two minutes there were only groups of two or three men running round wildly, like chickens with their heads off,” Abbott wrote of the Confederates. “We were cheering like mad….” Abbott described the horrific image of “both sides pegging away into each other” at close range, and how “[t]he rows of dead after the battle I found to be within 15 and 20 feet apart, as near hand to hand fighting as I ever care to see.”2

Abbott, whose older brother Ned had been killed at the Battle of Cedar Mountain in 1862, was particularly shaken by the death of his friend Ropes, who was hit during the preparatory bombardment. Abbott confessed that “Henry Ropes’ loss I felt as I should a brother. Such a pure hearted, generous and brave a gentleman I shall never meet again.”3 Despite the Union victory, Abbott, whose regiment lost 10 of 13 officers and 117 of 231 enlisted volunteers, could only resign himself to the ordeal, and what might come next. “Indeed with only two officers beside myself remaining, I can’t help feeling a little spooney when I am thinking,” Abbott wrote to his father, “& you know I am not at all a lachrymose individual in general. However I think we can run the machine.”4 Abbott had turned 22 when he fell at the Battle of the Wilderness the next year.

Facing Abbott on Cemetery Ridge was Captain Henry T. Owen, 32, of the 18th Virginia Infantry, part of Garnett’s brigade, Pickett’s division, of James Longstreet’s corps, Army of Northern Virginia. Owen survived the assault, but more than half of the 12,500 attacking Confederates who made Pickett’s Charge with him were killed or wounded in about an hour. He was one of only two men in his company left standing when it was over.5 A citizen-officer like Abbott, the nightmarish experience also changed Owen.

In a remarkable letter to his wife, Owen described how he continued to be haunted by dreams of the attack on Cemetery Ridge. “We were advancing in line of battle upon the enemy troops on my right and left shot dead away as far as the eye could see all pressing on the fearful conflict,” he wrote his wife in December. “I could hear the fearful reports of five batteries of cannon and the perpetual roar of fifty thousand muskets while a dark cloud of smoke hung over the field mantling everything as the gloom of dusky sunset. Far away to the front I saw the dim outlines of lofty hills, broken rocks, and lofty precipices which resembled Gettysburg.”6

As is sometimes the case in dreams, Owen understood where he was and what was happening, but also suffered the real sense that something was disturbingly off-kilter. “As we advanced further I found we were fighting that great battle over again and I saw something before me like a thin shadow which I tried to go by but it kept in front of me and whichever way I turned it still appeared between me and the enemy,” he recalled. “Nobody else seemed to see or notice the shadow which looked as thin as smoke and did not present myself to the enemy distinctly thru’ it.” The figure frightened him, and Owen described how he tried to escape it. “I felt troubled and oppressed but still the shadow went out before me. I moved forward in the thickest of the fray trying to lose sight of it and went all through the Battle of Gettysburg again with the shadow ever before me and between me and the enemy.”7

Owen struggled to make sense of these images. “[A]nd when we came out beyond the danger of shot it [the figure] spoke and said to me ‘I am the Angel that protected you. I will never leave nor forsake you.’ The surprise was so great,” he confessed, “that I awoke and burst into tears.” Owen found himself faced with a consequence of enduring a near-death experience, and his dream account is remarkable. In the many hundreds of Civil War-era diaries and letters I have read, it is rare for 19th-century soldiers to write about dreams with such vivid detail and clarity, and Owen’s account could have been written by a modern veteran dealing with post-traumatic stress disorder, survivor’s guilt, or other combat-related traumas. Owen made sense of the ordeal by ascribing his survival to divine providence. “What had I done,” Owen wondered, “that should entitle me to such favors beyond tho’ hundreds of brave and reputed good men who had fallen on that day leaving widowed mothers and widowed wives, orphan children and disconsolate families to mourn their fates?”8

We can learn something from these two officers. In a society that can seem increasingly divorced from the reality and consequences of war, combat is something that occurs on a screen or on the news. For most young Americans not serving in the military, a video game feels more real than modern war. Even key decision-makers, whose responsibility it is to determine whether and how to commit armies to combat, risk sharing that same dislocated sense of reality. Attempting to understand the experiences of soldiers like Abbott, Owen, and others can be a remedy for our greater failure to remember, and to pass on, fundamental lessons about the decisions and deeply personal consequences of past conflicts like our own Civil War.

That bloody summer in Pennsylvania also reminds us to never forget the spiritual component to war. War devours what it touches, including the human spirit. The spiritual component must never take second place to the physical—always a danger in a culture conditioned to favoring the practical over the impractical, or to reducing the human cost of war to abstractions. As we consider how military decisions affected the Civil War, we would benefit from letting the human stories never be overshadowed by the armchair analysis common in military history. The human lessons were central to the historical thinking of Pete Carmichael, and I hope he would agree that we ought to “listen” to men like Abbott and Owen, who knew too well how the consequences of military decisions could echo through their lives, and the lives of generations that followed.

Andrew S. Bledsoe is associate professor of history at Lee University in Cleveland, Tennessee. He is the author of Citizen-Officers: The Union and Confederate Volunteer Junior Officer Corps in the American Civil War (Louisiana State University Press, 2015); co-editor, with Andrew F. Lang, of Upon the Field of Battle: Essays on the Military History of America’s Civil War (LSU Press, 2019); and author of the recently released Decisions at Franklin: The Nineteen Critical Decisions That Defined the Battle (University of Tennessee Press).

Notes

1. Henry Livermore Abbott to Dear Papa, July 6, 1863, in Robert Garth Scott, ed., Fallen Leaves: The Civil War Letters of Major Henry Livermore Abbott (Kent, OH, 1991), 184–191, 188.

2. Ibid.

3. Henry Livermore Abbott to My Dear Oliver [Holmes], July 28, 1863, in Fallen Leaves, 194–196, 196.

4. Henry Livermore Abbott to Dear Papa, July 6, 1863, in Fallen Leaves, 184–191, 186.

5. Henry T. Owen to My dear Wife, December 21, 1863, in Kimberly Ayn Owen, et. al., eds., The War of Confederate Captain Henry T. Owen (Westminster, MD, 2019), 111–112, 111.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.