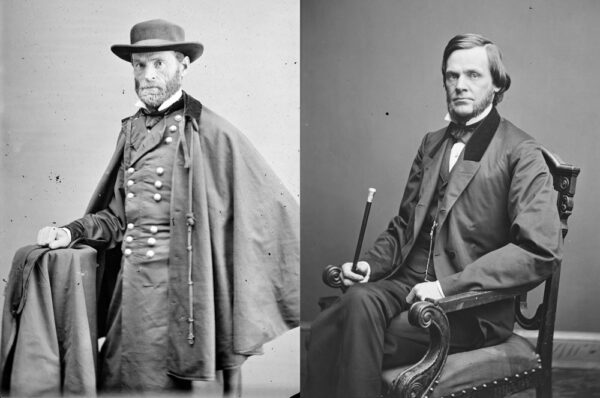

AI photo Illustration by John Huet

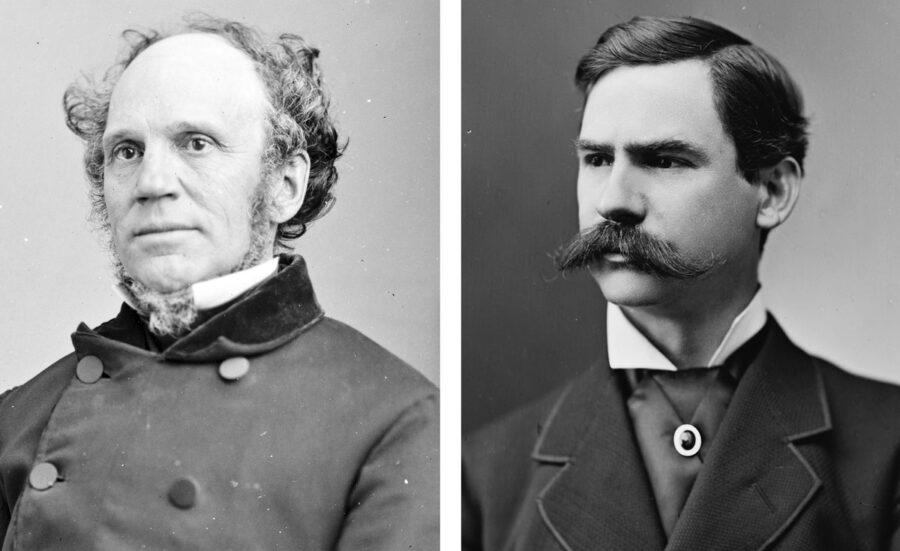

AI photo Illustration by John HuetConfederate General James Longstreet (left) and Union General Ulysses S. Grant

In March 1867, James Longstreet was thriving.

He was regarded in the former Confederate states as one of the great heroes of the Civil War, having commanded the Army of Northern Virginia’s fabled First Corps, and won laurels in Confederate victories at Second Manassas, Fredericksburg, and Chickamauga, among other battles. Longstreet had been Robert E. Lee’s hardy and dependable “warhorse,” as Lee put it. After the war, Longstreet settled in New Orleans, where he achieved economic success working as a cotton broker and was widely admired by his fellow Confederates.1

But what a difference a few months made. By June 1867, Longstreet’s reputation was in tatters. He had become a pariah in New Orleans and across the South, reviled as a traitor to his party, his country, and his race. What had he done to so antagonize his fellow southern whites? He had dared to publish four letters that spring announcing his support for Congressional Reconstruction, the centerpiece of which was black voting rights. These letters exploded like a bomb in the South and changed the course of Longstreet’s life. His embrace of Reconstruction infuriated ex-Confederates, who promptly cast him out of their pantheon of heroes—and then proceeded, in a decades-long campaign, to retroactively blame him for their defeat in the Battle of Gettysburg, and for their loss of the war.

The vast majority of scholarship on Longstreet has revolved around the question of whether, militarily speaking, he deserved this fate: Longstreet’s performance as a commander in the Civil War, especially at Gettysburg, has been litigated over and over, in painstaking detail, with various verdicts rendered. But his remarkable postwar political conversion—the very event that sparked the endless debates over his military leadership—has never been fully explained. Longstreet’s decision to support Reconstruction launched him on a lifelong career as a Republican political operative and national celebrity, whose iconoclastic positions on race relations, sectional reunion, and military history kept him consistently in the public eye. Longstreet’s about-face was the convergence of many factors: His wartime disillusionment with Confederate leadership; his sense of personal loss, sparked by the wartime deaths of three of his young children; and his exposure to the unique political climate in New Orleans all played a part. But the at the heart of Longstreet’s political conversion was his complex relationship with “the man who was to eclipse all,” as Longstreet put it: namely his prewar friend and postwar mentor, Ulysses S. Grant.2

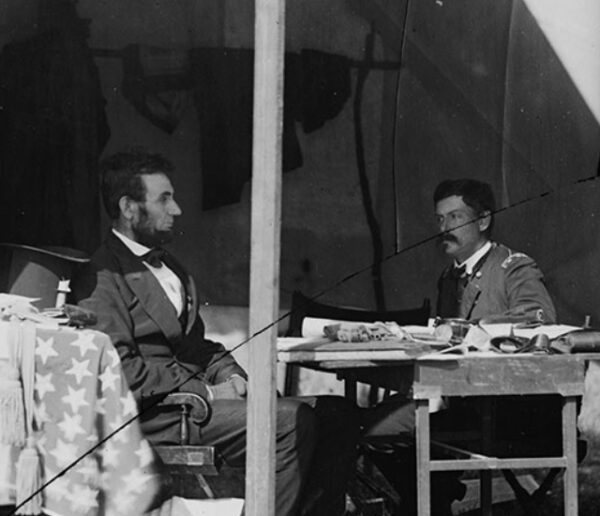

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia CommonsJames Longstreet’s friendship with Ulysses S. Grant, forged as cadets at West Point, grew in the decades before the Civil War, during which Longstreet attended Grant’s wedding and fought with him in the Mexican War. Shown here: A depiction of the 1847 Battle of Molino del Rey, where Grant earned Longstreet’s praise for his “superb coolness and courage under fire.”

“Pete” Longstreet and “Sam” Grant, as they were known to their classmates, met at West Point in the early 1840s when they were both cadets there; though they came from very different backgrounds, the physically imposing, prank-loving Georgian and the quiet Ohioan quickly became best friends. After their respective graduations, Longstreet and Grant were both posted to Jefferson Barracks, Missouri, where the steady routine of military drills and exercises and garrison duty was pleasantly punctuated by each man’s courtship of his future wife: Grant wooed Julia Dent, a distant cousin of Longstreet’s mother, while Longstreet courted Maria Louisa (Louise) Garland, the daughter of his regimental commander, Lieutenant Colonel John Garland.

The young soldiers soon tasted combat in the Mexican War; they both performed well in their duties, although their perspectives on the conflict were quite different. While Grant would, in retrospect, deem the Mexican War a wicked one, needlessly provoked by President James K. Polk’s aggressive deployment of troops in the disputed territory between the Nueces and Rio Grande rivers, Longstreet accepted the Polk administration’s arguments that Mexico had provoked the war. As Longstreet would put it in 1885, reminiscing on the war’s origins, “the Mexicans were committing outrages which called for repression at the hands of the United States.” Longstreet’s position reflected his upbringing in plantation society and his strong commitment to southern proslavery ideology and westward expansion; his political mentor in his formative years was his uncle Augustus Baldwin Longstreet, a fiery and influential defender of slavery and states’ rights.3

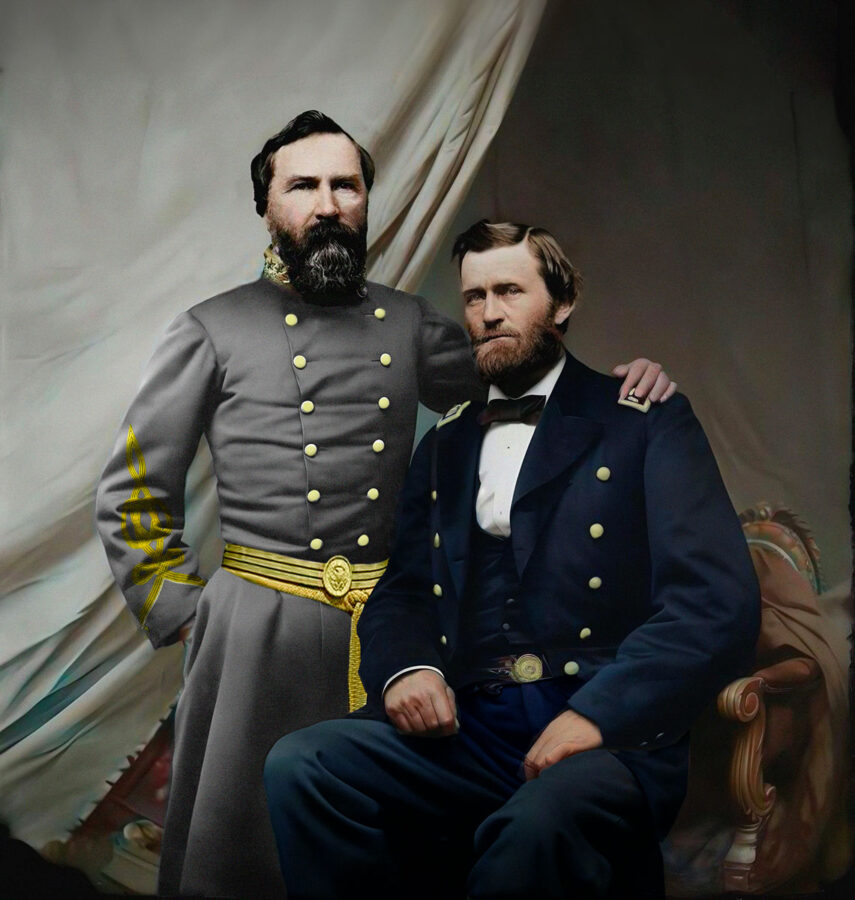

Library of Congress

Library of CongressWhile he was devoted to the Confederate cause, Longstreet’s confidence in it waned as the war dragged on—especially after his old friend Grant moved east to take on the Army of Northern Virginia. “[W]e cannot afford to underrate him and the army he now commands…. For that man will fight us every day and every hour till the end of this war,” Longstreet wrote of Grant. Above: In a painting by Henry Alexander Ogden, a somber Longstreet gives George Pickett the order to advance his troops at Gettysburg on July 3, 1863, a failed attack that would later be known as Pickett’s Charge.

Longstreet had surprisingly little to say, in public statements over the course of his life, about the significance of the Mexican War. But he did often take the opportunity to praise the battlefield conduct of Grant. At the 1847 Battle of Molino del Rey, Longstreet recalled in 1890, he “had occasion to notice [Grant’s] superb coolness and courage under fire”—qualities that foretold Grant’s future success. At the close of the war in 1848, the two men’s bond remained strong. A few months after his own March 8, 1848, wedding, Longstreet and his bride, Louise, attended the August nuptials of Grant and Julia Dent in Missouri.4

“Why do men fight who were born to be brothers?” Longstreet would ask plaintively after the Civil War, looking back on how sectionalism drove a wedge between the two men. Longstreet’s and Grant’s life paths diverged dramatically during the 1850s and would not cross again until the two men met at Appomattox in 1865. Grant, who had resigned from the army in 1854, was a staunch Unionist who condemned secession as “illogical as well as impracticable.” Determined to do his part in putting down the rebellion, Grant returned to the U.S. Army in June 1861 as the colonel of an Illinois regiment. Longstreet, in lockstep with his uncle Augustus and his Deep South relations, chose disunion after Abraham Lincoln’s 1860 election. For secessionists like Augustus Longstreet, the ascendancy of Lincoln’s Republican Party represented a political revolution: the eclipse of slaveholders’ power to control the U.S. government, and the specter of social equality, of “high, low, white, black, male, female—all on a level,” as his uncle warned. James Longstreet wasted no time in joining the rebel ranks. He was appointed a lieutenant colonel in the Confederate infantry in March 1861 and accepted that appointment on May 1, even before he had tendered his official resignation from the U.S. Army and before the War Department accepted that resignation.5

Longstreet was a true believer in the Confederacy’s racial politics and fought tenaciously for southern independence until the bitter end. As a military commander, he gave stem-winding speeches to his troops condemning Yankee radicalism, and he tried to preempt and to punish the many forms of black resistance to the Confederacy, such as blacks’ flight from their enslavers and their volunteering as spies, scouts, and soldiers to the Union army. Longstreet aggressively sought to forestall and undermine emancipation, through acts such as seizing free blacks during the Gettysburg Campaign and sending them south as slaves.6

Early in the war, Longstreet’s military star rose in the eastern theater as Grant’s rose in the western one. But Longstreet’s fortunes turned sour. While his belief in the Confederate cause did not waver over four long years, his confidence in it did. As Confederate infighting, strategic miscalculations, and logistical woes hampered the war effort, Longstreet began to brood over the fatal flaws that beset southern society—especially its hubris. “It is a bad principle in war to despise your enemy,” Longstreet wrote at the start of the doomed Knoxville, Tennessee, campaign of the winter of 1863, while he was temporarily posted in the West. It is no coincidence that Longstreet struck a despondent note at this juncture, for it was the first time he found himself in the same theater of war with Grant. In Longstreet’s view, Grant, who “was not lightly to be driven from his purpose,” could make the Confederates pay for their blunders and dysfunction in a way no other Federal commander could.7

Longstreet’s personal confidence was shaken both by Grant’s presence and the Confederates’ failure to appreciate what a grave threat Grant posed. “I know him through and through,” Longstreet warned, as Grant carried his relentless style of warfare into the eastern theater in 1864. “[W]e cannot afford to underrate him and the army he now commands…. For that man will fight us every day and every hour till the end of this war.” This warning proved prophetic as Grant’s attritional strategy wore down Lee’s army during their epic yearlong showdown in Virginia. After being grievously wounded in the May 1864 Battle of the Wilderness, Longstreet dutifully reentered the fray in October 1864. He ricocheted thereafter between the poles of defiance and despair: He remained committed to the cause but was increasingly dispirited by the Confederate army’s logistical woes and by the flagging morale of southern soldiers and civilians alike.8

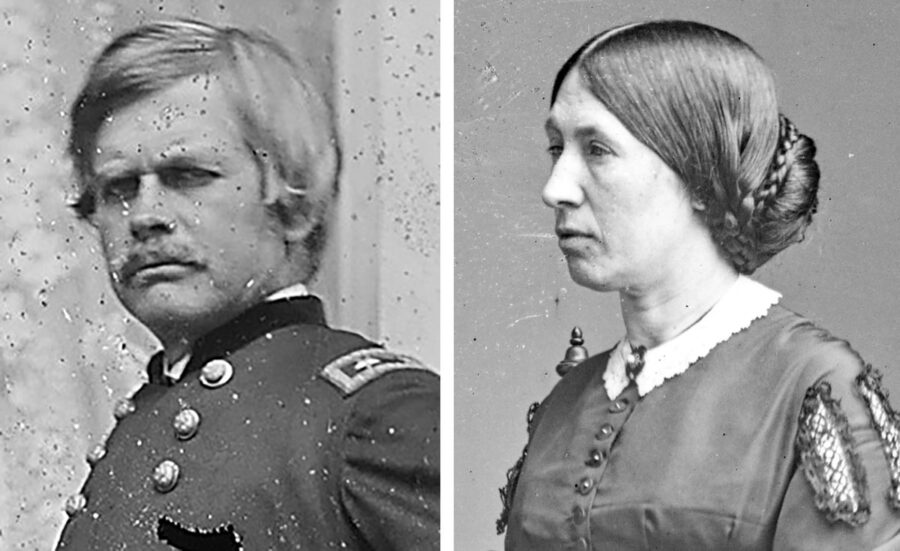

In late February 1865, after Lincoln’s reelection in the North crushed Confederate hopes that a new Democratic administration might concede southern independence, Longstreet explored the prospects of a negotiated peace: one that would secure amnesty and restore political and property rights for Confederates, and perhaps even remunerate them for the loss of their slaves. Together with Union major general E.O.C. Ord, an old West Point friend and conservative Maryland Democrat who commanded Yankee forces on the James River, Longstreet concocted a far-fetched armistice scheme. Grant and Lee would meet between the lines to conduct peace negotiations, while simultaneously a second channel of communication would be opened between Louise Longstreet and Julia Grant; as the women were old friends, they could enact women’s traditional roles as social mediators and represent the potential rapprochement between North and South.

National Archives (Ord); National Portrait Gallery (Grant)

National Archives (Ord); National Portrait Gallery (Grant)E.O.C. Ord (left) and Julia Dent Grant

Longstreet secured the endorsement of Lee and Jefferson Davis, while Ord consulted Grant, who cryptically tendered his approval of a plan for Louise Longstreet, and Longstreet’s entire family if necessary, to be sent to Grant’s headquarters and then northward—even as he made clear he disapproved of his wife playing any role in negotiations. Grant evidently saw no harm in a consultation among military leaders that could set the stage for Confederate surrender. But the scheme unraveled as Grant, consulting with Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and with Lincoln, received stern orders not to negotiate with Lee or to let up the military pressure on the Rebels. Grant wrote Lee on March 4, 1865, throwing cold water on the “military convention” idea and suggesting that Longstreet and Ord had misconstrued Grant’s meanings and intentions. Ord and Longstreet returned to the business of fighting.9 Although the armistice scheme fizzled, it had some significant consequences. It was widely covered in the northern press, bringing Longstreet a great deal of publicity as a man in the thick of the peace process. The episode was an occasion for Longstreet to signal that his friendship with Grant set him apart from other Confederates—and the primary audience for that signal was none other than Grant himself. Grant would soon confirm that he received the message loud and clear.10

***

The Confederate military collapse in March and April 1865, resulting in the fall of Richmond and Petersburg and the Army of Northern Virginia’s flight west toward Appomattox, inaugurated the famous correspondence between Lee and Grant broaching the topic of surrender. Grant’s April 7, 1865, note to Lee invoking the “hopelessness of further resistance” met with a truculent response from Longstreet, who clung to the idea that the Confederates themselves might dictate the terms of peace. “Not yet,” Longstreet advised Lee, hoping that some additional leverage or concessions might yet be secured by fighting on.11

But Grant was carefully laying a trap, with Federal armies converging on Appomattox north and south of the river—a trap Lee was unable to slip. On April 8, the Federal cavalry seized the Confederate supply trains at Appomattox Station, occupying the high ground west of Appomattox Court House, and blocking the Lynchburg Stage Road. This set the stage for Lee’s last breakout attempt on the morning of the 9th; its failure forced Lee to agree at last to Grant’s proposal that he capitulate. During the tense cease-fire that preceded the meeting at the McLean House, Longstreet attempted to dispel Lee’s forebodings that Grant’s terms would be harsh: “I assured him that I knew General Grant well enough to say that the terms would be such as he would demand under similar circumstances.”12 Longstreet’s reading of Grant’s intentions was vindicated. On April 9 at the McLean House at Appomattox Court House, Grant offered Lee surrender by parole. In exchange for their pledge that they would never again take up arms against the United States, Confederates would effectively be set free. “Each officer and man will be allowed to return to their homes, not to be disturbed by United States authority so long as they observe their paroles and the laws in force where they may reside,” the terms stipulated.13

Grant intended for his leniency to secure Confederate repentance and compliance. That was to prove impossible. Abundant testimony from the men in Lee’s army reveals that many held out hope that the war was somehow not yet really lost. They made their way to their homes, the historian Caroline Janney has noted, “awaiting a renewed call for battle.” Longstreet, by contrast, personalized the surrender terms, viewing them through the lens of his old friendship with Grant. He understood the terms in precisely the spirit Grant intended them: as an invitation for southerners, errant brethren, to return to the fold.14

Library of Congress

Library of CongressBefore the surrender meeting at the McLean House in Appomattox took place, Longstreet reassured Robert E. Lee that he “knew General Grant well enough to say that the terms would be such as he [Lee] would demand under similar circumstances.” Shown here: Painter and lithographer Otto Boetticher’s depiction of Grant, Lee, and their staffs meeting on April 10, 1865, at Appomattox, the day after Lee’s formal surrender.

In Longstreet’s telling, a brief encounter he had with Grant on April 10, 1865, was broadly symbolic of the promise of national reunion. They crossed paths that day at the McLean House, where Longstreet and other commissioners of the two armies were hashing out the details of the parole process. When Grant saw Longstreet, he extended his hand in friendship, “with his old-time cheerful greeting,” and they embraced. “Grant acted as though nothing had happened to mar the ties that had existed between us before the war,” Longstreet later recalled. “He put his arm within mine … and said with the same affection as of old: ‘Pete, let’s go back to the good old times, and play a game of brag as we used to.’” Grant’s act of personal grace would have an enduring impact on Longstreet’s politics and his postwar fortunes.15

Longstreet wasted no time in formally renewing his fealty to the Union, taking the oath of allegiance in May 1865 and approaching President Andrew Johnson, the Tennessee Unionist who took office after Lincoln’s assassination, to obtain a pardon; such presidential intervention was necessary to restore the rights of high-ranking Rebels. Grant promptly endorsed this pardon bid, writing, “Longstreet is really one of the least objectionable officers lately engaged in rebellion & would no doubt be willing himself to return to citizen ship.” Although Johnson rejected Longstreet’s initial request, Longstreet’s appeal for amnesty won him favorable newspaper coverage in the North, as Grant’s endorsement of Longstreet’s application was public knowledge. Their restored friendship was folded into an emerging popular narrative that cast soldiers as disposed to bury the hatchet and politicians as the sources of ongoing strife.16

That strife intensified as Johnson’s policies emboldened recalcitrant Confederates. In his two years as president, Johnson, abandoning his wartime alliance with the Republican Party and reasserting his identity as a Southern Democrat, granted pardons to former Confederate leaders permitting them to return to power in the South. Johnsonian state governments, through harsh regimes of “black codes” and extralegal violence, pushed freedpeople into states of subordination as close as possible to slavery, as southern whites terrorized blacks in shocking attacks such as the New Orleans massacre of 1866. President Johnson essentially went to war with the Republican Congress, vetoing its efforts to grant freedpeople the basic rights and protections of citizenship.

DeGolyer Library, SMU

DeGolyer Library, SMULongstreet, who renewed his fealty to the Union at war’s end, issued several public letters in support of Reconstruction in 1867, which ignited a firestorm of criticism in the South. above: Longstreet and his wife, Louise (seated together at far left), are shown here during a visit to Galveston, Texas, in 1866.

As Johnson’s erratic behavior alienated the northern electorate, Republicans secured the power they needed to institute their own policies. Congress’ own more stringent program, spelled out in the Reconstruction Acts it passed in March 1867, divided the former Confederate states into five military districts, and placed each district under the purview of a commanding general. These military commanders were to supervise the registration of voters—including African-American men and excluding some unpardoned Rebels—to elect delegates to conventions that would draft new constitutions and set up new state governments. Congress was establishing, in essence, biracial Republican governing coalitions for the South.

***

In Louisiana, Congressional Reconstruction went into effect in March 1867 under the direction of military governor Philip Sheridan. It was opposed and decried by former Confederates, most of whom were Democrats and supported Johnson. This was the setting in which Longstreet, invited by the local press to weigh in, offered up the first of his controversial letters. On March 18, Longstreet wrote to the New Orleans Times the following: “There can be no discredit to a conquered people for accepting the conditions offered by their conquerors, nor is there any occasion for a feeling of humiliation. We made an honest, and I hope I may say a creditable fight, but we have lost. Let us come forward, then, and accept the ends involved in the struggle…. Let us accept the terms, as we are in duty bound to do.”17

Longstreet developed this theme in three subsequent public letters. It was the duty of the defeated South, he insisted, to “abandon ideas that are obsolete.” Among the things he classed as obsolete was the Democratic Party itself, which was nothing more, he said, than a vehicle for old “prejudice.” Moreover, he directly addressed the issue of race relations, casting black suffrage in the South as a fait accompli and arguing that the experiment of black voting should be extended to the North and “fully tested.”18

Longstreet’s letters ignited a firestorm. Southern newspapers opposed to Reconstruction dissected them in a spirit of mounting wrath and incredulity. They cast Longstreet as “alone in his apostasy,” classing him with Benedict Arnold for his “wanton, wicked desertion of his friends and his country.” “It has become a subject of regret that the wound he received at the Wilderness was not mortal,” the Mobile Daily Tribune editorialized. “We would then have been spared the mortification of seeing him in the bum-boat of radicalism, side by side with the enemies of his country and race.” As the most prominent former Confederate to join the Republican ranks, Longstreet had set a potentially dangerous example.19

What motivated Longstreet’s about-face? Multiple factors were at play, but at the heart of Longstreet’s transformation was his admiration for Grant. In Longstreet’s view, Grant’s lenient terms at Appomattox reflected the victorious general’s moral courage, and required of the defeated Confederates that they display moral courage too: the courage to change their convictions, and to accept the death of slavery and of the Confederacy. Rewarding this reading of the terms, Grant provided Longstreet with approval and encouragement. “I have seen with great interest your two letters on the duties of the South in the present circumstances,” Grant wrote Longstreet on April 16, 1867. “These ideas freely expressed by one who occupies a position like yours, have to exercise a beneficial influence,” Grant added. Grant’s support helped Longstreet secure congressional amnesty, removing his disabilities, in June 1868; he was thus cleared to hold state or federal office.20

In Longstreet’s eyes, Grant—the cool, disciplined, honorable soldier—was the antithesis of the vain, volatile, reckless Andrew Johnson. Grant and his magnanimity represented the prospect that “the South, purified from the blight of human slavery … would grow, and flourish,” as Longstreet put it in an interview with a northern reporter. “The dallying policy of Andrew Johnson,” by contrast, “fed the spirit of the South with false hope of recovering the supremacy they had lost.” Longstreet lamented the “infernal tyranny of politicians, who will hold on as long as a breath of popularity remains to the most fossilized or exploded political theories.”21

Increasingly disgusted by Johnson’s incompetence, Grant endorsed Congressional Reconstruction and black voting as the means to safeguard the Union’s victory at Appomattox. Chosen as the Republican Party nominee in 1868 to face off against the Democrat Horatio Seymour, Grant campaigned as the candidate who stood for “both sectional harmony and the guarantee of the freedpeople’s newly gained political and economic freedoms,” as the historian Joan Waugh has put it. Longstreet publicly endorsed Grant during the presidential race, describing him as “my man,” adding, “I believe he is a fair man” who would bring a “complete and prosperous restoration of the Union.”

This assessment flew in the face of the conservative South’s emerging Lost Cause creed, which cast Grant as a merciless butcher and corrupt Radical Republican puppet. Longstreet also rejected, in some telling ways, Lost Cause orthodoxies on slavery and race. President Johnson and the Southern Democrats repeatedly argued that any black political participation would lead inexorably to “negro supremacy”: They cast race relations as a zero-sum game in which any gains for blacks would result in losses and indeed abject subjugation for whites. Longstreet renounced this racist propaganda. He was coming to believe that a limited kind of biracial politics was possible—that blacks could be constituents in the South and even exercise some authority and leadership, in alliance with peaceable whites.

***

Grant’s victory over Seymour set the stage for Longstreet’s own political career. The Republican press cultivated Longstreet’s loyalty by praising the “brave and noble stand” he took in the presidential campaign; “Grant is said to be very friendly to him, and will show his friendship next March in some unmistakable manner,” the New Orleans Republican predicted. In contrast with the “extreme harshness,” as Longstreet put it, of his Confederate critics, the Republicans seemed willing to let him finesse the issue of loyalty. They commended Longstreet’s military prowess and his political courage, reckoning that the more prominent he had been as a soldier, the more significant he could be as a symbol of repentance.22

National Portrait Gallery

National Portrait GalleryGrant’s victory in the presidential election of 1868 paved the way for Longstreet’s own political career, which began in 1869 after Grant (depicted here as president by artist Thomas Le Clear) appointed his old friend to the position of Surveyor of Customs for New Orleans.

Longstreet’s deepening commitment to Reconstruction was conditioned, to no small extent, by the singular political environment of New Orleans itself. The city, with its cosmopolitan culture, entrepreneurial energy, and demographic diversity, seemed fertile soil for political transformations to take root—should the federal government provide the necessary support and protection. As the historian Caryn Cossé Bell has noted, the undaunted “activism and republican idealism” of the city’s distinctive Afro-Creole population, led by veterans of the United States Colored Troops, meant that Louisiana would draft “one of the Reconstruction South’s most advanced blueprints for change”: a bold new state constitution that proclaimed the equality of all men, required the state to establish integrated schools, and prohibited segregation in public transportation and some public spaces.23

White conservatives mounted a swift backlash against the emerging new order through an extensive network of secret paramilitary political organizations, such as Louisiana’s Knights of the White Camellia. These groups, awash in a culture of paranoia and hatred, believed that “the need to restore white rule justified every means, every sadistic impulse, every enormity,” as historian Ted Tunnell has put it. White supremacist terrorists committed over a thousand political murders in Louisiana in 1868, enabling Seymour to defeat Grant in the state and undercutting the Republicans’ claim that Grant’s overall victory in the election constituted a mandate for Congressional Reconstruction.24

The stakes were thus dauntingly high when on March 11, 1869, Grant appointed Longstreet to the plum patronage position of Surveyor of Customs for New Orleans. Grant’s nomination of Longstreet received extensive press coverage, as a wide range of stakeholders debated whether Grant’s choice was an act of nepotism (given that Longstreet was distant kin to Julia Grant); an olive branch to the South (heralding conciliatory treatment to ex-Confederates); or a recognition of Longstreet’s own moral courage in defying the South’s unreconstructed Rebels.25

National Portrait Gallery (Seymour); Library of Congress

National Portrait Gallery (Seymour); Library of CongressHoratio Seymour (left) and Henry Clay Warmoth

On April 3, 1869, the Senate confirmed the appointment by a vote of 25 to 10, only one vote more than a quorum. Longstreet symbolized, for many northerners, the hopes of southern contrition and sectional reconciliation. In a bold show of generosity, the Christian Recorder, the Philadelphia-based organ of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, commented, “Of our white fellow-citizens, we ask not the question ‘What were you? Union or rebel?’ We simply ask ‘What are you? Are you for Union? For liberty?’” Since Longstreet had answered the last two questions in the affirmative, he received the paper’s “hearty congratulations.”26

Longstreet proved to be a dedicated and influential party operative. He served as a go-between for fellow Republicans President Grant and Governor Henry Clay Warmoth, deciphering the complex politics of Louisiana for the president. The Republican Party was deeply factionalized, as rival rings grappled bitterly over federal and state patronage. Longstreet initially allied with Warmoth against a so-called Custom House ring led by Grant’s brother-in-law James F. Casey, the collector of customs. Hoping to build a centrist coalition, Warmoth, a Union veteran from the North, appointed Longstreet adjutant general of the new racially integrated state militia, hoping Longstreet could mediate between the militia’s ex-Confederate and Republican elements. But Longstreet’s militia service only drew him deeper into the political maelstrom. In 1872 the Casey ring tried allying, out of pure opportunism, with New Orleans Democrats to undermine the Warmoth administration in the upcoming state legislative session. Chaos ensued, with brawling between legislators and the mobilization of rival forces in a series of street battles that sealed New Orleans’ reputation as a tinderbox.

Warmoth was increasingly unnerved and embittered, and drifted into the ranks of the Liberal Republicans, bolters who broke with Grant and favored removing Federal troops from the South and granting broad amnesty to Confederates. Longstreet briefly considered following Warmoth in this retreat from Reconstruction. But he instead chose to remain loyal to Grant, supporting his reelection in 1872. In Louisiana’s bitter gubernatorial election that year, Longstreet backed the pro-Grant faction led by Union veterans William Pitt Kellogg (a white northerner) and P.B.S Pinchback (a black southerner).

Longstreet would remain a stalwart Grant Republican as state politics descended deeper into violence. The January 1873 swearing-in of Kellogg as governor resolved nothing. The defeated challenger, the Democrat John McEnery, refused to yield, and instead set up a shadow government in New Orleans. McEnery called up his conservative militia, with former Confederate officer Frederick N. Ogden as its commander, and instructed it to seize the Kellogg administration’s militia arsenals and police stations. The ensuing clash was a debacle for the Ogden forces, as Longstreet’s units and Federal troops outgunned McEnery’s followers, forcing them to disperse.27

Kellogg rebranded the militia as the “National Guard of the State of Louisiana” and entrusted its expanded First Division, consisting of over 2,000 men, to Longstreet. The division consisted of four brigades, two of which were commanded by black brigadier generals: state senator Alexander E. Barber, an outspoken proponent of civil rights legislation, and Thomas Morris Chester, an accomplished lawyer, journalist, and activist. These were among the first black men in American history to hold the rank of brigadier general. Longstreet conspicuously supported and praised black militia units and their officers in public settings such as musters and parades.28

Enraged at the specter of black militarization and racial equality, conservative whites cynically used false rumors of a black uprising to mobilize armed whites for a takeover of the government. In the Battle of Liberty Place, on September 14, 1874, Longstreet, leading the interracial New Orleans Metropolitan Police and state militia, fought to defend the Republican state government against a violent coup by the White League, a white supremacist paramilitary full of Confederate veterans and allied with the Democratic Party. Longstreet was wounded in the battle and deeply demoralized. It took Federal troops sent by Grant to pacify the city.29

In the wake of what would also be called the Battle of Canal Street, Longstreet gradually shifted his political base from New Orleans to Gainesville, Georgia, where he would resettle. But his fighting days were far from over. For even as he left behind the dangerous terrain of Louisiana politics, Longstreet ventured deeper into the battlefield of Civil War memory. In 1872 a group of Confederate veterans in the late Robert E. Lee’s inner circle had begun to pin the Confederate loss at Gettysburg on Longstreet, charging him with delaying the crucial attack on the Federal left flank on July 2, 1863. Longstreet’s detractors explicitly connected his alleged wartime treachery and his postwar conduct in Louisiana—indeed, the more deeply Longstreet became implicated in Republican politics, the more receptive white southerners became to the criticisms of his war record. The editors of the Dallas Herald wrote in October 1874, for example, that they had not at first believed the charges against Longstreet. But since his appearance “at the head of the metropolitan police, prepared to hurl his messengers of death upon the citizens of New Orleans,” the editors proclaimed, “we withdraw our incredulity and are prepared now to believe that no deed of infamy could be named or conceived that [Longstreet] would not gladly be a party to.”30

In the aftermath of Reconstruction, Longstreet tried to build up Georgia’s Republican Party and craft a new network of alliances among black Republicans in Georgia. He continued to hold public office, as a Gainesville postmaster, U.S. marshal for Georgia, American minister to Turkey, and federal railroad commissioner. His main priorities, though, were to defend his military record and to fashion himself as a herald of sectional reconciliation. He published a series of articles between 1877 and 1887, in popular forums such as Century Magazine, in which he argued that he had favored defensive fighting in the Gettysburg Campaign, only to be overruled by Lee. Longstreet’s articles failed to blunt his critics’ attacks and the Lost Cause faithful across the South rallied to the defense of Lee; Longstreet in turn vowed to set the record straight by publishing an extensive memoir of the Civil War.

Grant’s death at 63 in 1885, after an agonizing battle with throat cancer, was heartbreaking for Longstreet, but also inspirational. As Grant’s biographer Joan Waugh has written, “by the time of his funeral Grant had become as much a symbol of national reconciliation as he was earlier a symbol of uncompromising Union victory.” During his prolonged, painful illness, Grant had “bask[ed] in an unanticipated but welcomed wave of tributes from former enemies,” gestures that “tipped Grant’s inclination towards embracing sectional harmony.” National reunion became the keynote of the national mourning for Grant.31

Feeling the loss of Grant’s friendship keenly, Longstreet fostered the image of the war hero as a peacemaker. On July 23, 1885, the very day of Grant’s death, a grief-stricken Longstreet was visited in Gainesville by a New York Times reporter. After noting that they had been “on terms of the closest intimacy,” Longstreet described Grant as “the truest as well as the bravest man that ever lived,” and “the highest type of manhood America has produced.” Longstreet contrasted Grant’s commitment to reconciliation with Jefferson Davis’ stubborn defiance, saying, “Mr. Davis never did give up ‘the cause’ as entirely lost. He expects to be President yet.”32

As he prepared his memoir, Longstreet used interviews and speeches to press the case that Appomattox was the defining moment of his postwar career—that he took part in Reconstruction out of gratitude to Grant and to uphold the terms of his Appomattox parole. The northern public was entranced by stories of the two men’s friendship, as is evidenced by accounts such as a May 1892 Philadelphia Times piece, sentimentally subtitled “a real romance of the war,” that averred that Longstreet “always had quite as tender a spot for the Great Captain of the North, as the ‘silent soldier’ often showed for him.”33

Longstreet’s 690-page memoir, From Manassas to Appomattox, published in 1896, featured the theme of North-South reconciliation, even as it provoked Longstreet’s southern critics by drawing a sharp contrast between Grant and Lee. According to the memoir, Lee lacked some qualities of character—calmness, adaptability, generosity of spirit—that were exemplified by Grant. “They were equally pugnacious and plucky,” Longstreet wrote, but Grant had a key edge, as he was “the more deliberate.” “As the world continues to look at and study the grand combinations and strategy of General Grant, the higher will be his award as a great soldier,” Longstreet concluded. By highlighting Grant’s skill and leadership, Longstreet spurned the Lost Cause argument that the Union’s brute force had overwhelmed the Confederacy.34

Perhaps the most memorable rhetorical flourish of Longstreet’s memoir was his proposition that “those who are forgiven most love the most”: this catch-phrase summed up his gratitude for Grant’s leniency at Appomattox and subsequent role in helping secure him amnesty and political office. In his last years, Longstreet’s reputation was somewhat rehabilitated in Confederate eyes. With one-party Democratic rule reinstated in the Jim Crow South, he seemed less a threat than he had before. Ex-Confederates were increasingly willing to set his political career to the side and celebrate his wartime heroics, and accept the image of him as a symbol of reconciliation. “Let the Dead Lion sleep in peace,” the Birmingham Ledger of Alabama proclaimed when Longstreet, 82, died in 1904. “The heroic Longstreet needs no higher eulogy than the single phrase, He was the friend of Grant and Lee.”35

In recent years, Longstreet has undergone a different sort of rehabilitation. In the midst of our debates over Civil War memorialization, some commentators have suggested that Longstreet deserves a public monument in the South, to celebrate his postwar political courage. But the depth of Longstreet’s bond with Grant should not obscure the differences between the two men. Longstreet fought the Civil War to win it. If he had succeeded, slavery would have persisted—and his own remarkable reinvention would have never come to pass. It was Grant’s military triumph during the Civil War, his act of grace at Appomattox, and his principled commitment to Reconstruction, that made Longstreet’s reformation possible.36

Elizabeth R. Varon is Langbourne M. Williams Professor of American History at the University of Virginia. Her book Longstreet: The Confederate General Who Defied the South was recently published by Simon & Schuster.

Notes

1. James Longstreet, From Manassas to Appomattox: Memoirs of the Civil War in America (Philadelphia, 1896), 262.

2. Longstreet, From Manassas to Appomattox, 17. The best account of Longstreet’s military career is Jeffry D. Wert, General James Longstreet: The Confederacy’s Most Controversial Soldier (New York, 1993). For a recent overview and reappraisal of Longstreet’s military performance, see Corey M. Pfarr, Longstreet at Gettysburg: A Critical Reassessment (Jefferson, NC, 2019).

3. Amy S. Greenberg, A Wicked War: Polk, Clay, Lincoln and the 1846 U.S. Invasion of Mexico (New York, 2012); Courier-Journal (Louisville, Kentucky), July 25, 1885.

4. Brooklyn Citizen, January 23, 1890.

5. The New York Times, January 12, 1890; The Constitution (Washington, D.C.), December 21, 1860; Ulysses S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant, Vol. 1 (New York, 1885), 219.

6. For an example of Longstreet’s proslavery rhetoric, see his speech in the Richmond Daily Dispatch, June 23, 1862. On the seizing of blacks in the Gettysburg Campaign, see David G. Smith, “Race and Retaliation: The Capture of African Americans during the Gettysburg Campaign,” in Virginia’s Civil War, edited by Peter Wallenstein and Bertram Wyatt-Brown (Charlottesville, 2005).

7. Longstreet, From Manassas to Appomattox, 328, 466, 481–482; U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies 129 vols. (Washington, D.C, 1880-1901), Series 1, Volume 31, Part 3, 680.

8. Longstreet, From Manassas to Appomattox, 466; Horace Porter, Campaigning with Grant (New York, 1897), 47.

9. On the Ord-Longstreet plan, see Elizabeth R. Varon, Appomattox: Victory, Defeat, and Freedom at the End of the Civil War (New York, 2013), 30–33, and Terrianne Schulte, “A ‘Visionary’ Plan?”

10. For press coverage, see for example Philadelphia Inquirer, March 22, 23, 1865; Evening Star (Washington), March 20, 21, 1865.

11. Longstreet, From Manassas to Appomattox, 619.

12. Ibid., 627–628.

13. Varon, Appomattox, 53–60.

14. Caroline E. Janney, Ends of War: The Unfinished Fight of Lee’s Army after Appomattox (Chapel Hill, 2021), 32, 52–53; Weekly Inter Ocean (Chicago), Feburary 26, 1880.

15. The New York Times, July 24, 1885; Philadelphia Times, May 15, 1892.

16. Calendar entries, May 28, 1865, Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, ed. John Y. Simon (Carbondale and Edwardsville, 1985–2000), Vol. 15: May 1-December 31, 1865, 494–495 (hereafter PUSG); Cleveland Daily Herald, November 18, 1865.

17. New Orleans Times, March 19, 1867.

18. Ibid., April 7, June 8, 1867 (the June 3 and June 7 letters appear in the June 8 issue).

19. Macon Journal and Messenger (GA), July 3, 1867; Mobile Daily Tribune in Bossier (LA) Banner-Progress, July 6, 1867.

20. Grant to Longstreet, April 16, 1867, PUSG, Volume 17: January 1-September 30, 1867, 116–117.

21. Troy Times (NY) interview, reprinted in Daily Evening Express (Lancaster, PA), February 10, 1869; New Orleans Advocate, March 13, 1869.

22. New Orleans Republican, December 8, 1868; Donald Bridgman Sanger and Thomas Robson Hay, James Longstreet I. Soldier II. Politician, Officeholder, and Writer (Baton Rouge, 1952), 335.

23. Caryn Cossé Bell, “‘Une Chimere’: The Freedmen’s Bureau in Creole New Orleans,” in The Freedmen’s Bureau and Reconstruction: Reconsiderations, ed. by Paul A. Cimbala and Randall M. Miller (New York, 1999), 154.

24. Ted Tunnell, Crucible of Reconstruction: War, Radicalism, and Race in Louisiana, 1862–1877 (Baton Rouge, 1984), 153.

25. For a roundup of the press coverage, see New Orleans Advocate, March 27, 1869.

26. Christian Recorder, May 1, 1869.

27. For coverage of Louisiana factional politics, see Tunnell, Crucible of Reconstruction, 164-71.

28. James K. Hogue, Uncivil War: Five New Orleans Street Battles and the Rise and Fall of Radical Reconstruction (Baton Rouge, 2006), 70, 121; New Orleans Republican, October 25, 1870.

29. Hogue, Uncivil War, 116–143.

30. Dallas Herald in Lake Charles Echo (LA), October 10, 1874.

31. Joan Waugh, U.S. Grant: American Hero, American Myth (Chapel Hill, 2009), 237–240.

32. The New York Times, July 24, 1885.

33. Philadelphia Times, May 15, 1892.

34. Longstreet, From Manassas to Appomattox, 566, 630.

35. Longstreet, From Manassas to Appomattox, 634; Helen D. Longstreet, Lee and Longstreet at High Tide: Gettysburg in the Light of the Official Records (Gainesville, GA, 1904), 240.

36. Charles Lane, “The Forgotten Confederate General Who Deserves a Monument,” Washington Post, January 27, 2016.

Related topics: Ulysses S. Grant