Library of Congress

Library of CongressConfederate General John Bell Hood

Late in 1864, the Confederate effort to turn the tide in the West was reaching an inflection point. All that summer, the Army of Tennessee, first under the command of General Joseph E. Johnston, then General John Bell Hood, had tried to fend off the implacable advance of Major General William T. Sherman’s Union army in north Georgia. By autumn, Atlanta had fallen, Hood’s army was in retreat, and Confederate prospects looked bleak.

Hood, along with Confederate president Jefferson Davis and General P.G.T. Beauregard, in a supervisory role, conceived a bold counterstroke: an invasion of Tennessee staged from Georgia or Alabama, with the aim of recovering Tennessee and enticing Sherman into a vain pursuit north. The strategic wisdom of such a tactic is debatable. But a question in keeping with the theme of this column is how the Confederate leadership executed it and, specifically, how Hood’s indecisiveness profoundly affected the later campaign.

On October 22, the Army of Tennessee set out from Georgia toward Guntersville, Alabama, where Hood intended to cross the Tennessee River. The river remained the major obstacle to a northern invasion, and Hood hoped to make the crossing at Guntersville, or perhaps near Gadsden. To protect his flank and rear in Georgia and to maintain pressure on Sherman’s supply lines between Atlanta and Dalton, Major General Joseph Wheeler’s cavalry was ordered to stay in position and screen the Army of Tennessee’s movements, but this left Hood’s intelligence-gathering capabilities diminished. Brigadier General William H. Jackson’s cavalry brigade accompanied Hood’s army, and Hood ordered Major General Nathan Bedford Forrest, whose cavalry was close to Jackson, Tennessee, to meet up with him after the army crossed the river.

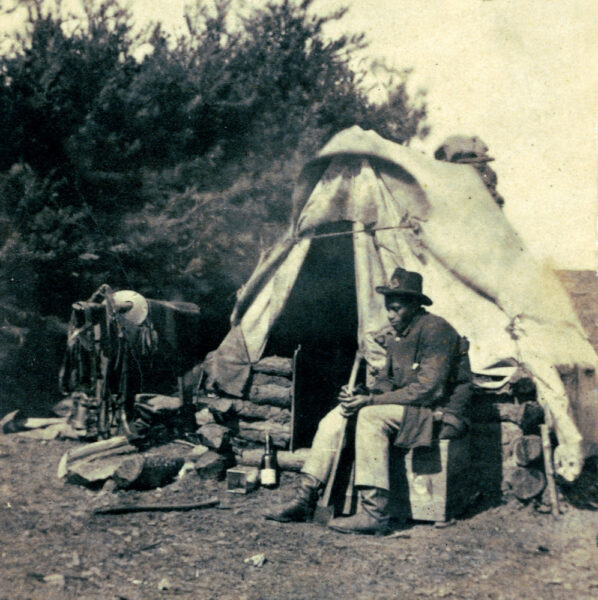

National Archives

National ArchivesP.G.T. Beauregard

The Army of Tennessee’s supply base was relocated to Tuscumbia, Alabama, and Beauregard, who had stayed in Gadsden to take care of logistical issues, finally followed Hood out on October 24. By then, Hood had discovered the Federals were at Guntersville, though his exact knowledge of their position is unknown. There were several possible solutions. Hood might carry out his original plan to cross at or near Guntersville in order to bring his army across the river as quickly as possible. (Wheeler’s cavalry remained in Georgia while Forrest’s cavalry was across the river in middle Tennessee, too far away to be of immediate assistance.) Hood was aware that, depending on the strength of the Federal troops and their level of opposition, a contested crossing could be disastrous. Getting an army across the river presented substantial challenges and with adversaries contesting it, the entire invasion plan might be derailed.

Such a crossing would also have been dangerous without Jackson’s cavalry to safeguard Hood’s supply lines, screen his army, and reconnoiter the enemy. On the other hand, the invasion might be disastrously postponed if he groped for an alternate crossing place farther upriver, giving the Federals more time to set their defenses and sacrificing the initiative and element of surprise Hood had planned for with a swift advance.

Hood decided, fatefully, to look for a more secure crossing location. Decatur, Alabama, about 40 miles west of Guntersville, seemed the likeliest option—but the issue of inadequate cavalry support continued to bedevil him. Hood could not know for sure until he went to Decatur whether it was a safer option than Guntersville, and that approach would unavoidably delay the invasion. If he tried to force a crossing as originally planned, that, too, might lead to delay and defeat.

Hood had a few other choices: He could move even farther upriver to potential sites at Courtland or Bainbridge, many more miles west of Decatur, or to Florence, farther west and closer to his supply base, assuming that both Guntersville and Decatur proved to be too dangerous to attempt. Given how little Hood knew about the Federal strength manning the river crossing, these alternatives were as murky as the Decatur option, and even less attractive given their potential for delay. A kind of paralysis seems to have descended on Hood, and as the days and hours passed, the situation worsened.

Beauregard, nominally in charge but physically on the sidelines, learned only after the fact that Hood had made a decision. Hood, as it turns out, decided to change his crossing to Decatur only when he had nearly reached Guntersville. Understandably disturbed by Hood’s unannounced change of plans, Beauregard caught up to him at Decatur on October 27. He “was surprised that no intelligence of this retrograde movement had been sent to him,” and “began to fear that General Hood was disposed to be oblivious of those details which play an important part in the operations of a campaign, and upon which the question of success or failure often hinges.”1

Meeting with Hood, Beauregard “cautioned him anew, in a more pointed manner, against the irregularity of his official proceedings, and openly expressed his regret that Hood had gone so far down the river to effect a crossing, a movement which would increase the distance to Stevenson[, Alabama,] by nearly one hundred miles, and give Sherman more time to oppose the march in force.”2

Hood assured Beauregard that he appreciated these objections, but that Guntersville was too hazardous and Decatur less problematic—reassurances given without his having a clear picture of either option or their potential repercussions.

As Hood explained:

It had been my hope that my movements would have caused the enemy to divide his forces, and that I might gain an opportunity to strike him in detail. This, however, he did not do. He held his entire force together in his pursuit, with the exception of the corps which he had left to garrison Atlanta. The morale of the army had already improved, but upon consultation with my corps commanders it was not thought to be yet in condition to hazard a general engagement while the enemy remained intact. I met at this place [Gadsden, Alabama] a thorough supply of shoes and other stores. I determined to cross the Tennessee River at or near Gunter’s Landing and strike the enemy’s communications again near Bridgeport, force him to cross the river also to obtain supplies, and thus we should at least recover our lost territory.3

Unfortunately, it turned out that a strong Federal force guarded the crossing at Decatur, and Hood’s hopes were dashed. Inconclusive skirmishing on October 28 ruled out further attempts to force a crossing, and so he decided to keep going west. When Courtland likewise proved unsatisfactory, Hood defaulted to Florence, 90 miles from the originally planned crossing at Guntersville. Even worse, Hood did not make it there until the last day of October, his invasion timetable now in disarray.

Hood again delayed, deciding to pause, gather 20 days of rations and supplies from the rickety Confederate railroads, and then ferry his army in phases across the river while he waited for Forrest’s cavalry to rendezvous with him on the northern bank. Forrest, meanwhile, was occupied with raiding near Johnsonville, Tennessee, and would not join Hood for some time.

Bad weather also intervened and rain and sleet pelted the countryside and muddied roads, delaying Forrest. Hood would not kick off the invasion without proper cavalry protection, and so his men huddled waiting in the rain and cold. On November 9, Union cavalry under Brigadier General John T. Croxton damaged Hood’s pontoon bridge, forcing the Confederates to repair it and further delay their river crossing.

In summary, Hood altered his strategy to cross with the Army of Tennessee at Guntersville due to apprehension about Federal threats, then revised his crossing location to Decatur, causing it to be postponed by several days. Following an unresolved encounter there on October 28, Hood once again modified his strategy, squandering crucial time. More time was lost in collecting supplies through the unstable Confederate logistical network while waiting for Forrest’s men to join them. Understandably, this caused leadership tension between Hood and Beauregard as concern grew about Sherman’s possible pursuit. Finally, on November 17, Beauregard relented and endorsed Hood’s proposal, ordering him to “take the offensive at the earliest practicable moment and deal the enemy rapid and vigorous blows, striking him while thus dispersed, and by this means distract Sherman’s advance into Georgia.”4

The Army of Tennessee did not completely cross the river until November 20. During this period, Hood’s uncertainty about the crossing and the interruption of the invasion schedule led to nearly a month’s worth of setbacks. The combination of weather and supply issues gave the Federals the opportunity to devise defense strategies, amass additional troops, and position their forces to withstand Hood’s invasion. By November 20, Hood’s attack on Tennessee had finally commenced.

But by then Hood’s indecisiveness had cost his army valuable time, initiative, and the element of surprise and led them to defeat. Sometimes indecision can itself be decisive.

Andrew S. Bledsoe is associate professor of history at Lee University in Cleveland, Tennessee. He is the author of Citizen-Officers: The Union and Confederate Volunteer Junior Officer Corps in the American Civil War (LSU Press, 2015) and Decisions at Franklin: The Nineteen Critical Decisions That Defined the Battle (University of Tennessee Press).

Notes

1. Alfred Roman, The Military Operations of General Beauregard in the War Between the States, 1861-1865, 2 vols. (New York, 1883), 2:286.

2. Ibid., 2:292-293

3. United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records 129 vols. (Washington, 1880–1901), Series 1, 39:1, 802.

4. Ibid., Series 1, 45:1, 649.