Historian Eric Michael Burke answers questions about the lives of Civil War soldiers and the weapons they used.

Transcript

Terry Johnston: Eric, thanks for joining us. Today we have several questions for you, all in some way pertaining to Civil War soldiers and soldiering. First up is one we received anonymously. It reads, “How often did Civil War soldiers engage in hand-to-hand fighting? Statistics seem to indicate that sword and bayonet wounds were rare. So was close-quarters combat something that only occasionally happened?”

Eric Burke: Well, thank you for having me on, first of all. The statistics on edged-weapon injuries, I’ve always kind of thought of them similarly to the Air Corps study during the Second World War on where a B-17 was being hit when they returned to base so that they could strap more armor onto the forts in order to avoid flak damage. And, it’s kind of a classic case study because what they found was, unsurprisingly, that the spots where the aircraft were really, truly vulnerable there was no data for. And that’s because those planes never came back to land in order for that data to be collected.

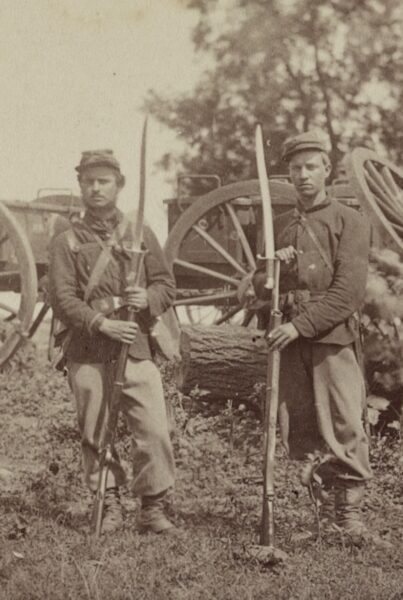

Library of Congress

Library of CongressUnion soldiers pose with their bayonetted rifles in a photo made in 1862.

And I know that there’s a lot of citation across Civil War historiography on the absence of edged-weapon injuries. Which is true. The medical history reports, insofar as those things were comprehensive, do indicate that there was a dearth of bayonet wounds and especially saber wounds. We know in more anecdotal evidence that plenty of people got stabbed by bayonets in the American Civil War. Just as plenty of people got stabbed by bayonets across the planet in the mid-19th century fighting in wars that involved bayonets or edged weapons. But I think the more important lesson to be drawn from the relative disparity between especially projectile wounds and edged weapons is that in the 19th century—and even to a certain extent today in infantry warfare, but especially in the 19th century—the edged weapon was far more a psychological instrument than it was intended to actually do physical damage to a combatant. So, 19th century officers, even amateur volunteers like American Civil War volunteer officers, would’ve been taught a kind of doctrine, if we can use that word for the time, that emphasized how infantry fire—and the same to a different extent with cavalry with sabers and whatnot, but because most of the combatants were infantry, we should stick with that—was thought of as the preparatory act, is what they would’ve called it, and then the bayonet is the decisive act. So what that meant in practice is that, unlike what you see often in, you know, Civil War reenactments and things like that, the goal was not simply to stand across from each other from however many hundreds of meters and just slam away indefinitely until the opponent more or less disappeared or left or just could not return fire anymore.

The entire purpose of fire was to prepare the enemy so that when a bayonet attack was delivered, the psychological trauma that had been created by the firefight was such that he would run. And if that goes right, as it does in the textbooks of the time of course, very few people get stabbed by bayonets. Because the point isn’t to stab them with the bayonet. The point is to tell you that if you don’t move, I’m going to stab you with a bayonet. And if you’re already traumatized because you’ve watched all your buddies falling over the last hour or however long that firefight has gone, you’re much more likely to say, “Well, you know what? All is lost. I’m going to, run away.” And that was the entire premise that undergirded all of infantry tactics during the war. Which is why you have men like Stonewall Jackson constantly belaboring the point that it’s all about the bayonet. You’ve got to move them with the bayonet.

And that wasn’t a mantra that was specific to any one officer. French officers at the time, and on into the first part of the 20th century would’ve said exactly the same thing. And that if you spend too much time pouring lead into the opponent and creating all of these projectile injuries, and you never close with the bayonet, then you are ultimately failing the test of the way these weapons systems are supposed to be employed on the battlefield.

Now, in the Civil War, because these are amateurs, because they’re volunteer armies, as many historians have pointed out very often things don’t quite get as far as they’re supposed to get, quote unquote, in the textbooks. So you get volunteers who are commanded by officers who frankly don’t have the skills that are required to move those men into the locations that they need to be in order to take advantage of the terrain to then take advantage of their fire and then transition from that into a bayonet attack. And as I’ve said in a lot of my work, the men responded to that in a way that developed a set of ideas and tactics themselves, if you will, that were designed not necessarily to not be successful in their tactical aims, but certainly to preserve their lives in the process of trying to navigate the situation where it was clear that their officers at every echelon were not super experienced at what was going on.

And what resulted, then, was a whole lot of usually super close range—because again, they’re amateurs, they don’t really know how to use these weapon systems correctly—really short-range exchanges of gunfire that were prolonged for really long periods of time. And that led to a massive increase in the number of projectile wounds. And because most of the time, I mean if we’re talking about raw stats, no one is bringing things to a full fruition with the bayonet. Not only is the bayonet not designed to be actually stabbed through somebody tactically, we’re not even getting close to that point. Instead we’re just exchanging fire from a close range distance. And nobody really thought a lot about how that was going to transition beforehand. Everyone was hopeful that mass itself was going to do it. And when it didn’t, these firefights sort of peter off. And then the two sides back away from one another—if you don’t have some, big surprise like Chancellorsville or something like that where a whole corps caves in.

So, I guess the quick answer that I would give to that question is that a lot of it is a result of both what the edged weapons of the era were designed to do—which, again, is to invoke psychological fear more than they were to actually be used violently—mixed with a broader systemic failure of these volunteer amateur armies to actually employ their weapons systems the way even the texts that they were learning from taught them that they were supposed to be employed.

All of these things lead to the common denominator of weapon systems at the time that are wedded to tactical systems, neither of which were being employed during the Civil War in the way that the system had been designed by the armies. And then ultimately that makes the disparity of edged weapon injuries another symptom or another example of evidence that shows you how the Civil War is so unique as a contemporaneous conflict. How it is so different from the war in Italy or Crimea. We talk a lot about the similarities that the Civil War had with these other conflicts by professionals, even Mexico at the time in 1863. I mean, there were a lot of bayonet injuries when the French raided Puebla in 1863, and were wandering through the fortifications, literally killing people with sword bayonets in close quarters battle. And that’s almost the same time that Grant is sieging Vicksburg.

So it’s not that bayonets weren’t used by infantry at the time. It’s that things weren’t going according to plan tactically in the continental United States during those eras as it related to infantry combat.

Terry Johnston: Yeah. And it makes me think of a quote I read once by a Union soldier in a letter or a diary that he used his bayonet a lot more as a makeshift candle holder than he ever did in battle. So that’s our first question for you. Let’s move on to the second one. This one comes from Gary in Alabama, and it’s regarding the aftermath of battle. He asks, “With all the dead horses and mules, not to mention all of the weapons and equipment laying on the battlefields after a fight, how and when were the battlefields cleaned up?”

Eric Burke: So a lot of this is dependent, I mean, there’s a lot of diversity in practice on this score. And a lot of that makes sense because battles weren’t all the same. They didn’t all happen at the same time of year. They didn’t all happen at the same scale. If you had a little skirmish between two cavalry detachments versus Culp’s Hill or Pickett’s Charge or the West Woods, I mean, those fights are on a catastrophic scale that obviously leaves behind a great deal more detritus, both human, animal, and material, than anything else. And most things fall on a continuum between those things. And many historians—Megan Kate Nelson’s book Ruin Nation does an excellent job at getting at these questions, Meg Groeling’s Aftermath of Battle does a lot with burials and how we get from a field that’s just carpeted with lines of fallen men to what we think of today as these big national cemeteries or state cemeteries and local cemeteries for a lot of the Rebel dead. But one topic that doesn’t get addressed—though both of those books deal with it in part—is the material detritus.

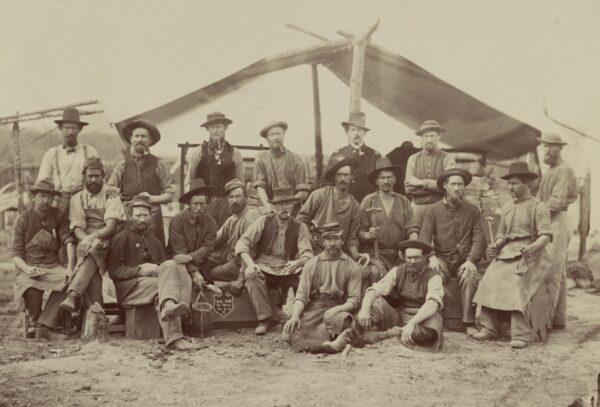

Library of Congress

Library of CongressConfederate dead, and various battle detritus, left behind after fighting at Fredericksburg in May 1863.

So every time one of these weapons is fired you are littering the ground with spent percussion caps and obviously what’s left of the paper cartridge—the paper’s just going to disintegrate of course. But as weapons break, as pieces of the weapons break, as pieces of your cartridge box break off or your belt plate or whatever falls off and you’re under fire, you don’t spend a lot of time trying to figure that out. You just throw it on the ground and keep going. And that doesn’t require anybody to die to happen. I mean, I lose pocket change going to the grocery store. So, stuff falls out of your pocket just as a matter of being when you’re not in combat.

And a lot of that is of course unsurprisingly what relic hunters are out there finding all the time everywhere they go. And there’s still a great deal of it in the ground. Probably most of it is still in the ground after 150 years. If it was metal or something that at the time was either hidden in grass or dirt or just wasn’t worth anything to anybody, so they just didn’t care, then it remained out there. And the scale of a fight coincided with the amount of detritus that would be left out there. One of the big things that does affect questions like this though, is that so much of the fighting, especially out east, took place in ground that was under cultivation at the time. Because if you were going to marshal these numbers of men and utilize the weapon systems at the kinds of ranges that they were designed to be—well, they were never really used at the ranges that they were designed to be, but somewhere close—you needed more open area. And fortunately, in the 1860s in the eastern states, far more of the acreage out there was under open cultivation than it was in the West.

What that also means, though, is that so many of these fights are happening in farm fields that as soon as the battle is over—and provided that you don’t have some kind of literal holocaust that took place, so bad that the field is just more or less useless—it’s going to be under cultivation almost immediately afterward. And that means ultimately that plows are going to be going over that stuff and plows aren’t cheap. And thus farmers are going to want to spend the time of going through their field, taking the time probably with family members and other community members insuring that the ground is cultivatable after something like that, after somebody comes in and finds as many of the bodies as they can. And as we know, even now, we still find bits and pieces of human remains on all these fields. That happens from time to time, fortunately less now than it did in the past. And fortunately, now we’ve got DNA that can help us figure out who was who. But ultimately it was usually a community enterprise.

The one caveat to that I will say is that the United States Army—both armies, but just for an example, the United States Army—dependent upon the pace of the campaign and the tempo of the campaign and the nature of the campaign—Shiloh is a great example of an army that stays put for quite some time. And thus because of that, because your cantonment is on the same field where the fight happened and your company is sitting or lying on the ground on blankets and rubber ponchos surrounded by stinking detritus of war, human and animal and everything else. It is then the army that takes care of that. The Army’s, of course, going to salvage anything that is of use. If there are just rifles that are, you know, bayonetted into the ground like in the movies that are still usable, nobody’s going to just leave that there. That stuff’s going to be collected. But there is ultimately going to be a lot of stuff that’s just ‘who cares,’ you know, ‘moving on.’

The Army’s also then going to do a lot of the mass burials of the dead that then later families and the Sanitary Commission and others are going to come in and dig those bodies up and reinter them. The horses—for the most part, getting rid of a dead horse, there were a couple of different methods that that tended to be used. Usually, they were burned. Sometimes, if you’re on a march and a horse had heat exhaustion, there were plenty of occasions where the horse was just left to rot like roadkill or anything else. But usually they were burned. And oftentimes, if an artillery team or a caisson team got splattered with grape shot and it took all the horses down, or most of the horses down, then they were usually in a group. You could wrap ropes around them, pull them together, pile brush on, or put brush under them, however the case may be, and then burn them all en masse. You can imagine how wonderful that smelled for a very long time. But insofar as there was a doctrine for removing dead horses, that was certainly the norm. You can also see plenty of photography, [Alexander] Gardner’s photography, [Mathew] Brady’s photography, any photography that was taken of a field after a fight, even if it was only a couple of weeks after a fight, there’s usually horse skulls or horse skeletons around. And, you know, a horse doesn’t convert to a skeleton in the timeframe that was necessary to take that picture. And that’s usually because the horse flesh was burned away. The photographer goes out there and saw a horse skull and, just like dragging a sharpshooter into Devil’s Den, realizes, boy, that’d be dramatic if I did that and put some cannonballs next to it. But what that is is evidence of the removal of the horse flesh before it started rotting and then obviously became a medical problem on top, or a hygiene problem on top of just rotting there.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressThis July 1863 image by Timothy O’Sullivan shows dead artillery horses on the Gettysburg battlefield.

Terry Johnston: Yeah. It strikes me too that at least part of this cleanup process would include what might have been called scavenging, right? Both by civilians and even soldiers.

Eric Burke: Absolutely. And that happened before anybody died. I mean, that happened before there was a battle. People would come out and try to see what they could find that was not perfectly guarded by people. And, obviously as we know, soldiers did that a lot too. But in the Immediate aftermath, just like after, frankly, any conflict— you think of the First World War instances where a lot of French civilians would come out and pick through the piles of expended shell casings and then go back and do these super-ornate artworks. You see, often in antique stores or militaria shops or whatnot these incredibly ornate works of art where you took a .75-millimeter casing brass and turned it into this statuette.

And the same types of things were going on in the American Civil War. Anything that anybody thought was worth anything and was just left behind. Certainly, as people were going through the field they would pick it up. And also, things that were identifiable to individuals were also very often collected. And we have many, many, many stories of folks showing up after the war to some farmhouse in Indiana, coming all the way from Alabama and saying, “Hey, I think you dropped this, at Resaca and I found it and it’s taken me 10 years to get up here to give it back to you, but it had an address on it, so I thought I’d come see if you were home.” And that kind of stuff happened. And every time you bump into it underscores one of the more uncanny aspects of any civil war throughout history where you’ve got two people who share a culture and a nation that fight each other. And then afterward, it’s kind of a collective lost and found effort that goes on.

Terry Johnston: Alright, great. Well, let’s move on to the next then. Mark from Connecticut asks, “What were the safest and most dangerous jobs in the infantry?” Why don’t we start with the safest.

Eric Burke: Well, I mean, it really depends on a lot of things. Because if you’re just talking about raw statistics, like if we get into a time machine right now and we go back to a rifle company or a volunteer infantry regiment in 1862 and we want survive, first of all we should bring penicillin. And that’s only half tongue in cheek because, I mean, in reality, statistically as we know, you are most likely to die of disease. And thus, that’s going to be tough not knowing anything about germ theory.

But the truth of the matter is that anything that helps you avoid a mass camp of instruction gathering in the beginning, especially if you’re from a rural state. If you are one of these later-joining, third- or fourth-call volunteers that comes in in 1863 or 1864, your odds are going to be higher because you’re not going to be exposed to a lot of the same antibodies and pathogens that the guys that you’re going to be joining have already been exposed to. Of course, they’re also going to be carrying things that you’re not exposed to. So you might die anyway.

But that’s not specific to the infantry. The most important thing to know about the Civil War and to think about as it relates to the Civil War is that the infantry itself was pretty homogeneous. It was completely homogeneous in terms of tactical skill sets. I mean, you were a rifleman, full stop, unless you were a non-commissioned officer, in which case you were usually also a rifleman. Or you were a commissioned officer, in which case that was your role. Obviously, it was dependent upon your situation. Sometimes it was far more dangerous to be an officer than to be an enlisted man or an NCO. But in general, I think if you average it out across the conflict probably about equally dangerous for everybody.

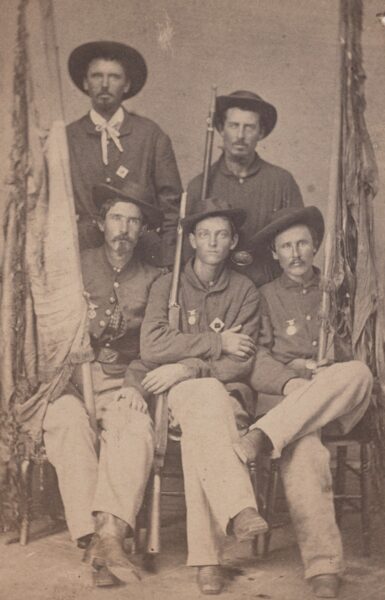

Library of Congress

Library of CongressQuartermaster’s mechanics from the Union army’s IX Corps at Petersburg, Virginia, in August 1864.

If you really wanted to survive and you wanted to be safe, it would be really great to get detailed out to maybe a quartermaster’s clerk position. Or some sort of very rear echelon position that usually was reserved, frankly, for people that had some sort of injury or some sort of debility at the time. Unless they had some special skill, like there were saddlers or blacksmiths or something like that. Those were also relatively safe positions.

But that didn’t mean that you weren’t going to be exposed to the same pathogens that everybody else is. I mean, if you’re just trying not to get shot then, yeah, those positions are the best to be doing. But that doesn’t necessarily mean, again, that you’re not going to die of measles or something else, which is what’s most likely to kill you anyway.

And that’s not to be scoffed at because, frankly, that’s what most of these soldiers were most scared of themselves. They didn’t wake up in the morning and say, “oh man, I hope there isn’t a big battle that goes on.” They woke up in the morning and said, “do I really want to go to the hospital for that cough that I’ve got?” Because if I do, I could die. Far more likely than I’m going to die in the next skirmish or whatnot is if I go get seen for that thing on my toe it could be the last thing I do. Because there’s so many people over there that are just deathly ill.

And then in battle, I think unsurprisingly just don’t volunteer for anything. That’s a really good general guide. It’s exceptionally hard when your brothers in arms that you care a great deal about are volunteering for things and then you’re caught in a hard spot. And then survival sometimes doesn’t always seem like the most important thing, at least momentarily. And that kind of segues into the more dangerous aspect of things. By far, statistically, the most dangerous thing you could be facing in combat is what in English would be called a forlorn hope, which is usually a body of volunteers that are incentivized by promises of leave home or a bounty or something like that in order to join a small group of men who are going move in advance of a main body that are assaulting some sort of fortified position. And your job is going to be usually to carry ladders, hopefully, explosives and all sorts of ammo in order to create a breach somewhere, usually through an abatis or in some sort of palisade or scarp. And that is just an extraordinarily dangerous business. Hence the name forlorn hope. Although that actually comes from the Dutch verloren hoop, which means more or less lost company. And that action of picking a group of people and sending them forward in order to create a breach in a fortification, I mean, that’s as old as the Romans. And that tactic had not evolved at all except that, you know, they were using explosives—powder bags—by the 19th century. But, I mean, the task itself was identical and it was just as deadly in the Roman era as it was in the 1860s. So, that is a profoundly dangerous thing to be doing. And in most cases, the majority of those men did not survive. And if they did, they were not unwounded. So if anybody asks you and our time travel adventure to become a member of the forlorn hope, if surviving is your number one mantra, it’s not a good plan.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressMembers of the 30th Ohio Infantry’s color guard pose with their tattered banners.

Terry Johnston: Yeah. And I’m thinking the color guard usually gets a big nod as a…

Eric Burke: Sure. Sure. Yeah. And you know, the big reason behind that is that, once again, not to besmirch the reenactments, because these things have to happen at distances that the spectators can watch and say, “Oh, okay, I see what’s going on.” In reality, if two infantry regiments are exchanging fire, I mean we like to say in the books it was like, “Oh, they were at close range. They were only at 150 yards.” But that’s a football field and a half apart. And if there’s anything in between you and if you’re firing at each other at even half the range that these rifles are designed to be fired at, you are shooting at the flag. You are shooting at the colors of the opposing regiment because much of the time, if they have fired anything at you, it’s a cloud of smoke with a flag sticking up over it. And thus, if you don’t have any marksmanship training to begin with, you’re going to be aiming about center mass where you see the flag sticking up, which is the same reason the flag exists, right? So that the officers of that side can find it and can move that unit around through the smoke or through the bushes or the trees or the vegetation or whatnot. And that necessarily means that a mountain of lead, most of the lead that is being poured at your unit, is going to be directed, however inartfully, toward the banners and whoever is holding them. So, yes, that would also be a rather more dangerous location to be if you were in the infantry.

Terry Johnston: Yeah. Well, okay, let’s move on. But before we do, let me make a promise to you, Eric, that if we ever do get a Civil War time machine question, you will be our expert of choice. Let’s lock that in. Alright, so next up is from Logan in Maine. And he asks, “What did the average infantryman on both sides do with their wages? How often were they paid and in what form?”

Eric Burke: So, they would’ve told you not often enough. If you were a Federal volunteer then, almost any time before the summer of 1864, you were making $13 a month. Which was not bad money. And more importantly, given that most of these kids, North and South, before they became soldiers they were digging hedge ditches and walking in between farms on back roads, trying to go up to farmhouses and figure out if anybody needed itinerant labor during the summer or during the spring. That is the mountain of the demographic that’s going to wind up in a volunteer company. That’s what they would be doing otherwise. And if the farm season is poor, then there is no $13 a month. There’s no $13 anywhere. And so you’re teaching at a schoolhouse or something like that for a few months the year, trying to find money. So, the regularity of money, ironically, for what I’m about to say, was in many cases ways one of the biggest pulls to take an 18-year-old, a 19-year-old boy and put him in a volunteer company in either army, regardless of patriotism, right? Because plenty of people were patriotic who didn’t wind up in the army. And we know a lot about the motivations debate.

But that $13 a month—or if you were a Confederate you were getting $11 a month until the summer of 1864, you got a $7 raise—that money was supposed to be dispersed by a pay master who was part of the regular army by doctrine. And that poor guy had to go around to a selection of volunteer commands. And he was supposed to be doing that every two months. That in practice usually became at least four months during the war. And often it could slide to even more than that. I mean, you might go half the year or more without ever seeing any kind of money whatsoever. And that does undergird where a lot of these desertion statistics come from because if you’re going through all this, not just the battle, but, you know, try to dodge sickness and everything else and you’re not being paid, it’s really easy to get to the point where you’re just like, “Okay, I don’t care much for this anymore.”

It also means that you don’t have any liquified capital of any kind. I mean, keep in mind that these guys didn’t, for the most part, come out of cash-rich economies to begin with. Greenbacks are a new phenomenon in this era. Most of them, they came from towns that had the kind of economy—I mean, insofar as a 19-year-old cares about it—they had ledgers at the general store and whatnot that I could go in, give my name, and then settle with that individual later. The same with farmers. So, that was the world that they were familiar with. And they found a very similar world in the army with sutlers.

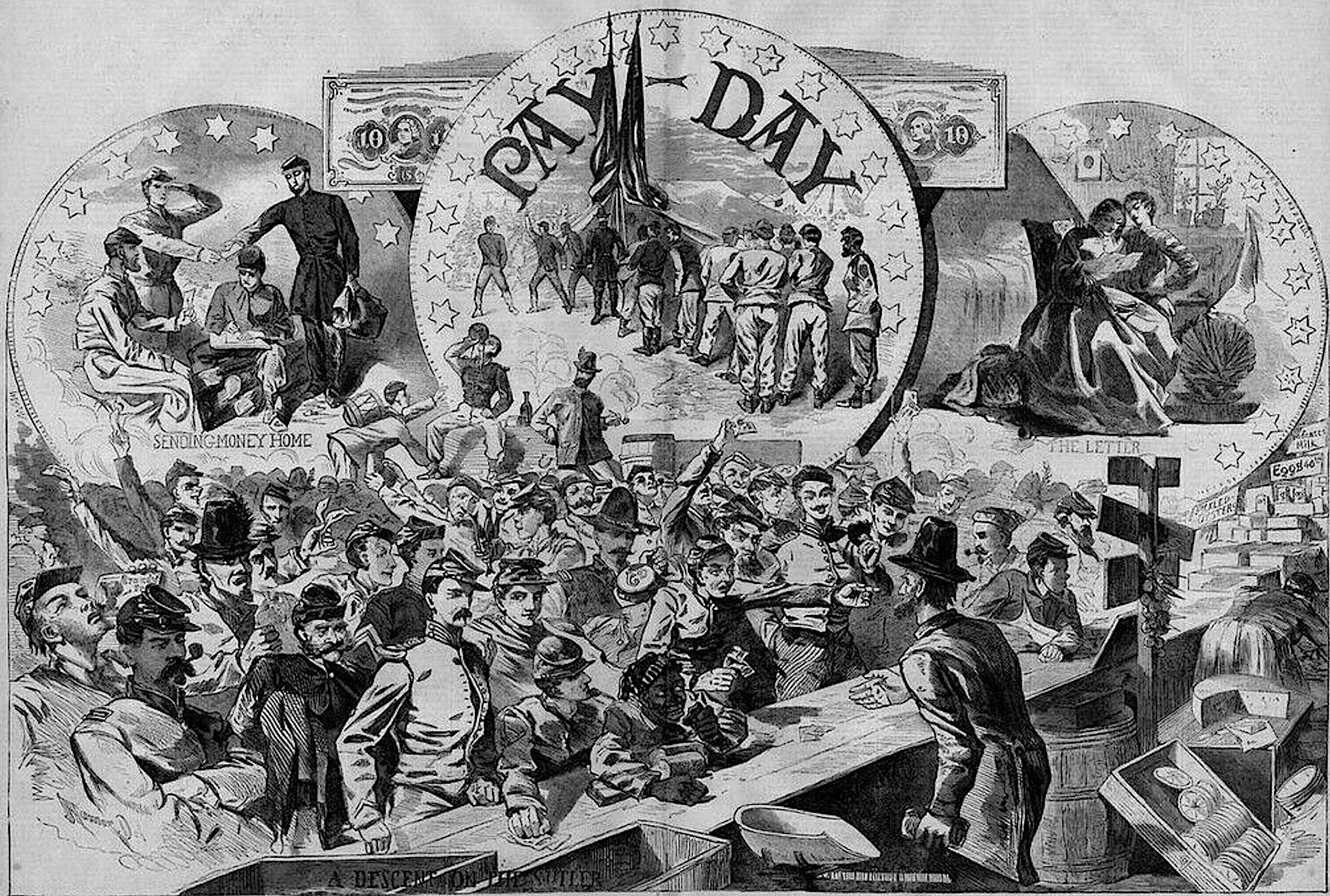

Harper's Weekly

Harper's WeeklyWinslow Homer’s “Pay-Day in the Army of the Potomac,” which appeared in Harper’s Weekly in February 1863.

And the sad fact of the matter is where did the money go? In a great deal of cases, most of it went to the sutlers. And much of that was because the money was so often delayed. And when it was delayed and you didn’t want to just eat salt pork and hard attack 24/7 and you were far more akin to going to get some soft bread and cakes and tobacco and everything else that the ration wasn’t sufficient in for your taste, you would go to the sutler and you would run up a debt. You would run up a credit, essentially, with the sutler. And then when the pay master finally did come around, at that point the sutler would be beside himself with anger because he is the one who needs the most money because you haven’t been able to pay him. And you’ve already drawn from the sutler months upon months’ worth of pay in all of the different things that you’ve bought. To say nothing of gambling debts, which were also replete in a normal volunteer unit, a bunch of teenagers and 20-somethings out there doing that type of stuff.

And then on top of that, if you had any allotments, which were common. Many soldiers, especially in second- and third-call volunteer regiments where you’ve got a lot of family men, would set up allotments for their families back home where they would get a certificate from the paymaster. And you mail that certificate to your family and then your family could use that certificate to go get your allotment for their use. And you can imagine with the unpredictability of the mails back then, I mean, that was a nightmare. And plenty of people were just mailing away certificates that were going to get sunk when a steamboat hit a snag, and then nobody has any money. There’s no proof of anything. And that’s going to turn into a pension claim in three years if you survive.

And, so, a lot of this money just disappears. It goes to the sutler. It goes to the allotment. There’s no cash exchange. If you lost your nipple wrench for your rifle or your overcoat fell off because you were hot, so you threw it by the side of the road or whatever. The army is to charge you for those things, and that’s also going to come out of your pay. And, thus, that meant that for a lot of these kids, because they weren’t great with money, as, frankly, young soldiers also aren’t today, nothing has changed there. Because they’re young and they have very little advice. There was no financial aid advisor in the Union army at the time. It was just these kids. And, so, they lost a lot of their money as they got it.

Those that didn’t, those that, you know, were teetotalling, very careful with every cent that they got. They could send it home. They could do any number of different things with the cash money that they received. I mean, obviously in the Confederacy it was depreciating rapidly over the entire course of the war. So, although you were getting paid $7 more after the summer of 1864, that money was worth almost nothing at that point. And once again, you see the rise in desertions. And I don’t mean to just say that all these guys are money grubbing, but I mean you’ve got to eat and your family has to eat So that was a major player there.

But the long and short of it is that most of that money went to debts. Very little of it was just, “oh man, I’m getting rich playing soldier.” And you see that in the letters, right? I mean, much of the letters home are almost always, “Hey mom, I’m almost out money.” And “we haven’t been paid in forever.” Uh, “I saw my cousin so and so from whatever regiment that’s camped next door and he spotted me some things that I needed. But we don’t know when we’re going to get paid. And even when I do, I owe the sutler so much money that I don’t think I’m ever going to get out of that debt and I can’t find my whatever the government issued me here recently, so I’m going to have to pay for that or they’re going to charge me later,” and so on and so forth. So, the system functioned insofar as it was designed to function, except that everything was massively delayed. But the fiscal responsibility, unsurprisingly, of a lot of these volunteers led to a whole lot of grief most of the time.

Terry Johnston: Yeah, I’m sure. Alright, Eric, well then one final question for you. This one’s from Bill in Illinois. And he asks, “What happened to the millions of muzzle-loading muskets and thousands of field artillery pieces when the armies mustered out in 1865?”

Eric Burke: So that’s a fascinating question. And it’s even more fascinating because, in many ways, the story of the weapons that are used during the war—other than the weapons that are produced, especially by the United States, during the war—the Civil War is sort of situated materially within the broader context of warfare as it is unfolding in the mid 19th century. A very large proportion, I don’t know that anybody has ever actually crunched the numbers on it, but a very large proportion of the weapons, small arms, and artillery, and especially the ammunition that is used in that conflict, is coming from somewhere outside of the United States. Obviously, the Enfield rifles that everybody knows so well. I mean, those are British. But you’ve got Austrian Lorenz, you’ve got weapons systems from just all over the world. And then, maybe appropriately, after the war many of the weapons—to include a great deal of the weapons that we produced—dispersed all over the globe.

Insofar as they were kept, in many cases soldiers were given the option, especially United States soldiers at the end of the war, to buy it. I mean, a rifle was not cheap at the time. But in many cases—not in all cases, but in many cases—they were offered the opportunity to purchase the rifle and take it home with them, just like they were given the option to purchase any of the rest of their gear. I mean, there’s that famous painting by Winslow Homer, “A Veteran in a New Field,” where you’ve got a guy in a hat and he’s mowing his top field. And if you look, he’s got an army-issued canteen and a fatigue blouse laying in the hay behind him because he bought that from the army when he left. And you could do the same with rifles.

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Metropolitan Museum of ArtWinslow Homer’s “A Veteran in a New Field.”

But I think in most cases, I mean, you’ve got well over a million small arms alone that were captured from the Confederacy at the end of the war. So you’ve got all of the arms that were purchased and produced by the United States during the conflict, plus the million-plus that are captured from the Confederacy. And the first thing that people—by people, I mean President Grant, eventually, and others in the late 1860s—wanted to disperse these in arms-trading agreements with other countries that wanted to pay us for them because they were involved in conflicts of their own. I mean, even during the war itself, or at least immediately after it, there was a bunch of hullabaloo about sending weapons potentially to the Mexican liberals trying to throw off the French-installed leadership that was part of Napoleon’s intervention down there. And that became a big tension point in Congress. Many of them went to Indians in diplomatic deals that were attempting to secure various aspects of the West. Many of them went to the Turks later in the 19th century. In fact, if I remember correctly, one of the more famous instances, there were some Ottomans that were like reservists that were killed defending an outpost in the First World War. And famously they were found with 1861 Springfield rifle muskets that they were armed with that the Turkish government had obtained from the United States after the war.

But I mean, they went back to the Brits, who in many cases sold them to the French. They went all over Europe. They went all over Asia, in various conflicts in that continent. And yeah, so there’s a massive proliferation of all of these small arms, which, of course, when you take your massive army and you shrink it to nothing more or less overnight, you don’t need all those guns. And we had, even by the end of the war, far more rifles than we needed, which is why you see these famously archeological expeditions that find whole corduroy roads that were more or less made of rifles just because they were handy and you don’t have to do as much work putting them down as you do cutting down logs and stripping the saplings and things like that. And then famously, they turn them into fences and things like that after the war because they were metal. And people melted them down in the First and Second World Wars for metal drives as well. And a lot of that happened with the artillery, which also was proliferated around the world but many of those were ultimately melted down because you could use that brass, or whatever the piece was that you’re talking about. But also a lot of those were distributed to towns or veterans organizations or things like that to display in front of your GAR monument. And a lot of those frankly are still out there today.

But the other main purveyor of those things after the war was a company, uh, Bannerman in New York that, especially around the turn of century, is really popular. They had a catalog, sort of like Sears Roebuck. And it was basically the world’s largest Army-Navy surplus store you could imagine, with entire artillery parks and all these weapons that had been bought up. And you could buy these things just straight out of a catalog, and they’d be mailed to your home. You want a cold Army revolver? Cool. You want a field howitzer? Cool, here’s the price point. And you send in your little mail-in certificates and there’s probably taxes on it but it ultimately comes to your house. And that, unsurprisingly, is no longer the case. But at the turn of the century, they had a great deal of the arms that still existed.

But the more interesting, as you can tell from my perspective, the more interesting part of the story is the proliferation of those weapons. They came into the country from elsewhere and then after the war they went out elsewhere. Obviously the Springfields are manufactured here. But, for the most part, the Civil War then becomes a kind of waypoint on the lives of those weapons that are going to pass through the United States and then go on and do in many cases even more terrible things elsewhere. So, it’s not a happy story, but it’s definitely part of what connects the Civil War to the wider world.

About the Guest

Eric Michael Burke, a U.S. Army combat infantry veteran of the wars in both Iraq and Afghanistan, is a historian of culture and warfare in Europe and the Americas. His first book, Soldiers from Experience: The Forging of Sherman’s Fifteenth Army Corps, 1862–1863, was published by LSU Press in 2022.

Eric Michael Burke, a U.S. Army combat infantry veteran of the wars in both Iraq and Afghanistan, is a historian of culture and warfare in Europe and the Americas. His first book, Soldiers from Experience: The Forging of Sherman’s Fifteenth Army Corps, 1862–1863, was published by LSU Press in 2022.

Additional Resources

- Megan Kate Nelson, Ruin Nation: Destruction and the American Civil War (2012)

- Meg Groeling, The Aftermath of Battle: The Burial of the Civil War Dead (2015)

- Mathew Brady’s “The Dead of Antietam”

- Military pay during the Civil War