Library of Congress

Library of CongressAbraham Lincoln

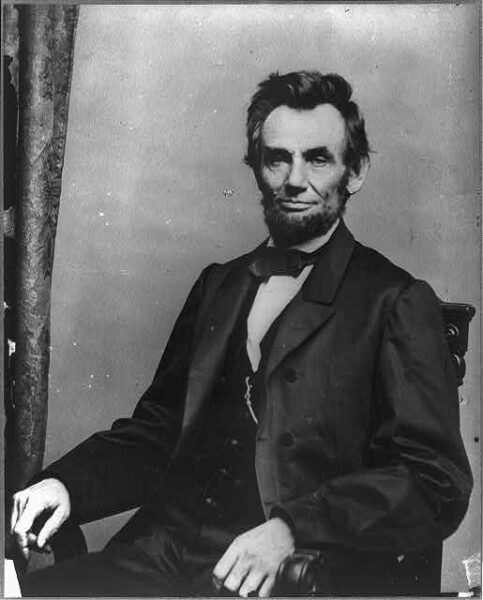

With the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence only a year away, there is bound to be plenty of reflection on the document and its legacy. It’s worth noting then, that among the leaders of the nation it created, none was a more fervent disciple than Abraham Lincoln.

Some of Lincoln’s political ideas are open to interpretation, but his deep respect for the Declaration of Independence is crystal clear. He spoke about the document thoughtfully and often, especially after his return to politics in the 1850s as an antislavery Republican. By 1861, the Declaration had become the core of his political identity. As he told the crowd at Independence Hall in Philadelphia only 10 days before assuming the presidency, “I have never had a feeling politically that did not spring from the sentiments embodied in the Declaration of Independence.”

What sentiments did he mean? As did most of his fellow Americans, Lincoln believed governments “deriv[e] their just powers from the consent of the governed,” but his thinking on the Declaration went deeper and fundamentally shaped how he defined freedom.

The passage in the Declaration that Lincoln quoted or alluded to most was its proclamation that “all men are created equal.” To recognize the idea’s centrality to his political philosophy, we need look no further than his greatest speech. The “four score and seven” opening to his Gettysburg Address encapsulates the time between Lincoln’s present and the Declaration’s past adoption. He then defines the document as having created a nation “conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”

Lincoln spoke those words on November 19, 1863, having spent at least the previous decade pointing to equality as the central idea of the Declaration. With increasing precision, he had repeatedly warned that slavery and the politics protecting it directly threatened the spread and perpetuation of equality in America.

This evolving persona had most clearly come into view in Lincoln’s fiery October 16, 1854, Peoria, Illinois, speech against the Kansas-Nebraska Act. After asking his audience whether a “negro” should be considered a “man”—a key word in the Declaration of Independence—or share the same status as livestock, Lincoln answers: “If the negro is a man, why then my ancient faith teaches me that ‘all men are created equal;’ and that there can be no moral right in connection with one man’s making a slave of another.” Certainly, Lincoln opposed slavery for economic, social, political, and moral reasons, but the foundation of his antislavery stance was that the institution was incompatible with the Declaration’s preamble because it set one race above another.

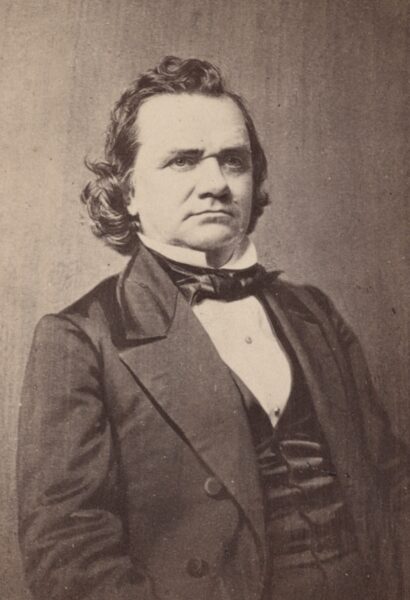

Library of Congress

Library of CongressStephen A. Douglas

This idea shows up repeatedly in Lincoln’s writing but is perhaps most clearly stated in an undated note he wrote himself later that decade. Perhaps clarifying his position before heading into the 1858 senatorial debates against Stephen A. Douglas—during which he repeatedly mentioned the Declaration’s commandment of equality as the basis of his antislavery stance—Lincoln defines his position on democracy as one that fundamentally connects it with equality and freedom. “As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master. This expresses my idea of democracy. Whatever differs from this, to the extent of the difference, is no democracy.”

How Lincoln viewed the Declaration’s guarantee of the right to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” is clear on the first two. By asserting that African Americans, enslaved or otherwise, were men and that no man has the right of mastery over another, Lincoln effectively extends life and liberty to everyone, regardless of race. How he broadly applied “the pursuit of happiness” is less clear.

Most people today would define “the pursuit of happiness” as—at minimum—equality under the law. Lincoln sometimes falls short of that principle. In that same 1854 Peoria speech, Lincoln frets he cannot envision a place for black people in a United States without slavery. “Free them, and make them politically and socially, our equals?” he asks. “My own feelings will not admit of this; and if mine would, we well know that those of the great mass of white people will not.”

Lincoln notoriously made even blunter statements during the Lincoln-Douglas Debates, declaring “I am not, nor ever have I been in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races.” He justified this position by explaining “there is a physical difference … which I believe will for ever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality.” Doesn’t this put Lincoln in conflict with his revered Declaration of Independence?

One of Lincoln’s gifts was his ability to keep an open mind and the subsequent crucible of civil war forced every American to consider what freedom and democracy meant. This is the primary concern of his Gettysburg Address, and while its opening establishes the primacy of the Declaration of Independence in the nation’s political identity, the speech’s end signifies how the war is changing that identity. After recounting the sacrifices of U.S. soldiers in almost religious terms, Lincoln implores his audience to “highly resolve … that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

Democracy must survive but it will be renewed. We’ll never know exactly what “new birth” Lincoln foresaw, but his actions elsewhere signal it was likely a recommitment to, or even redefining of, the Declaration’s ideal of equality. He had, after all, issued the Emancipation Proclamation at the beginning of that year and had witnessed mass efforts by enslaved people to win their freedom, including black soldiers serving in the field. A year later, he would win a second term committed to pushing a 13th Amendment through Congress that would abolish slavery in America.

But those are just the death knells of the “peculiar institution.” The broader equality we strive for today and would hope to see in Lincoln is there, if only in glimpses. As Confederate defeat became increasingly certain and he began to envision a postwar America, Lincoln started quietly endorsing black suffrage and public education. On April 11, 1865, having just returned from visiting the Confederate capital Richmond, he went public, stating “it is also unsatisfactory to some that the elective franchise is not given to the colored man. I would myself prefer that it were now conferred on the very intelligent, and on those who serve our cause as soldiers.”

This was a giant—if restrained—step forward for the Lincoln of the 1850s. It was bold enough that it reportedly motivated John Wilkes Booth to murder him—which Booth did three days later. Lincoln’s lifelong dedication to and interpretation of the Declaration of Independence ended tragically, but they bore fruit and their implications will reverberate to the coming anniversary.

Christian McWhirter is a historical consultant and the author of Battle Hymns: The Power and Popularity of Music in the Civil War. He previously served as the Lincoln Historian for the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum and as editor of the Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association.