For Union and Confederate veterans, the task of reconciliation proved a difficult one. After four years of bloody conflict, physical and psychological wounds lingered.

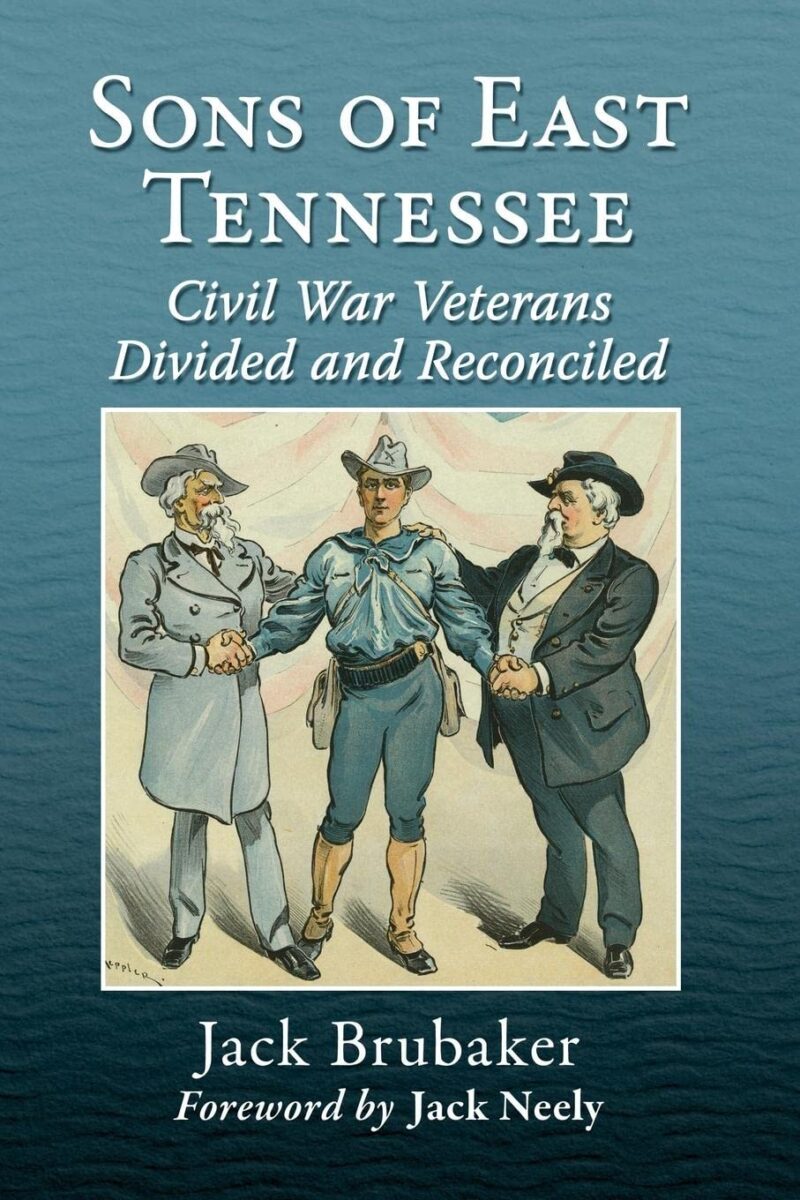

This was especially the case in East Tennessee, a region that contributed large numbers of troops to both the Union and Confederate armies. Focusing on the tale of two Civil War veterans (Reuben Bernard and William McCorkle) who fought on opposing sides but came together when their sons were killed during the Spanish-American War, Jack Brubaker’s Sons of East Tennessee documents how a culture of sectional reconciliation came to prevail even in a region notoriously divided.

Brubaker organizes his work around three themes: separation, reunification, and reconciliation. He recounts the war and its impacts on East Tennessee and discussed how the population recovered from the conflict. The author devotes considerable space to the work of burying the Civil War dead, which, he writes, “restrained efforts to reunite the living” (67). National cemeteries, after all, excluded the rebels, ensuring each side interred and memorialized their dead in separate spaces.

In East Tennessee, however, Union and Confederate veterans not infrequently attended memorial ceremonies together. By the 1890s, the bitterest memories of the conflict had largely dissipated. “Veteran organization,” Brubaker writes, elected “to emphasize the bravery of white soldiers on both sides rather than the causes or the horrors of a four-year bloodbath” (19).

Because of the physical proximity of veterans from both sides in East Tennessee, adhering to such a narrative was necessary for the region to recover from the conflict. By the turn of the century, “Tennesseans were united in their determination to go to war—under one flag.” They were afforded such an opportunity with the outbreak of the Spanish American War (103).

In the last section of the book, Brubaker shifts his focus to the sons of his protagonists, who took up arms in the Spanish American War. Both men served as officers during the conflict—and both perished at the Battle of El Caney on July 1, 1898.

When the hostilities ended, there was a growing desire to repatriate the remains of the hundreds of Americans (among them Jack Bernard and Henry McCorkle) who had lost their lives fighting in Cuba. Bernard and McCorkle, both graduates of the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, would be buried side by side with the consent of their fathers. Their final resting place became a conspicuous display of sectional reconciliation and national unity.

Drawing on a wide array of primary source materials, Brubaker’s Sons of East Tennessee contributes to the growing literature on veterans and the problem of Civil War memory. While on minor occasions the text includes some factual inaccuracies (most notably referring to President William McKinley as a general officer in the Union Army during the Civil War), his work effectively illustrates how a region divided during the war achieved reconciliation at an astonishing pace.

Riley Sullivan teaches U.S. history at San Jacinto College in Houston, Texas.