Dan Addision, University of Virginia Communications

Dan Addision, University of Virginia CommunicationsAlan Taylor, Thomas Jefferson Foundation Professor of History at the University of Virginia.

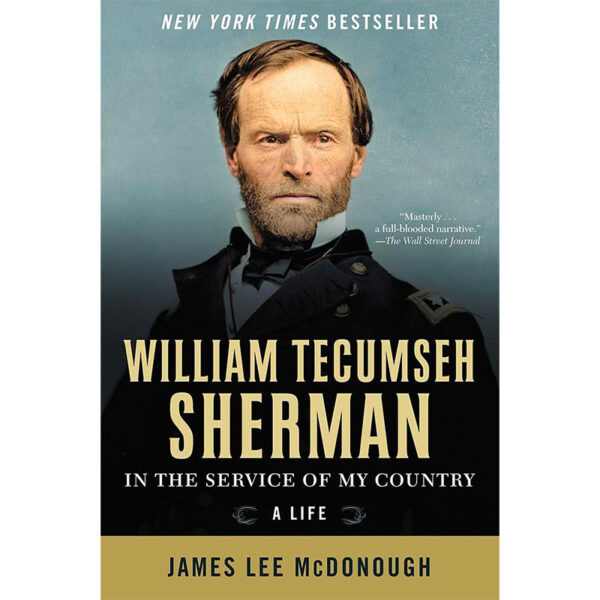

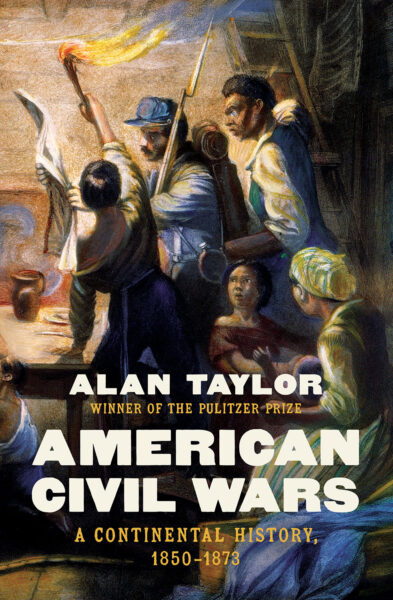

Alan Taylor, Thomas Jefferson Foundation Professor of History at the University of Virginia, is author of a number of works on American history, two of which—William Cooper’s Town: Power and Persuasion on the Frontier of the Early Republic (1996) and The Internal Enemy: Slavery and War in Virginia, 1772–1832 (2013)—were awarded the Pulitzer Prize in History. His latest book, American Civil Wars: A Continental History, 1850–1873 (published in May by W.W. Norton), considers America’s sectional conflict in the larger context of the transformative struggles taking place throughout North America at the time. We recently interviewed Taylor about how he came to the subject and, in writing the book, what he learned about the Civil War.

Much of your previous work has focused on America in the mid 18th and early 19th centuries. When and why did you decide to turn your attention to the Civil War era?

Starting with American Colonies: The Settling of North America, published in 2001, I have explored the history of North America to better understand the emergence and development of the United States. I extended that story into a series with American Revolutions (2016) and American Republics (2021). That last book brought the story into the 1850s, and I became curious to see how the continental scale would play out in the era defined by the American Civil War. That curiosity also emerged from my interest in the characters of that civil war, an interest that reached back to my childhood when I read Bruce Catton’s account of the 20th Maine Infantry. So I had to resist making Joshua Chamberlain central to the entire story of the continental era! As an academic historian, I continued to read about the era to inform the courses that I have taught on the American West, the survey of U.S. history, and the history of Canadian-American relations.

In the book’s Preface, you note that the American Civil War “was not the only civil war in North America” at the time. Where were these other civil wars, what were they about, and in what (if any) ways were they similar or connected?

In 1859–1860 and again 1862–1867, Mexico suffered from brutal and destructive civil wars that pitted Liberals, upholding a federal republic, against Conservatives, who favored a centralized authoritarian regime. During the same period, Canadian leaders wrestled with their own internal divisions, which seemed to deepen as the Anglophone population grew faster to outnumber the Francophones of Quebec. Talk of secession intensified in Canada just as that specter became real and devastating within the United States. The U.S. Civil War affected the entire continent (and beyond) as all three polities wrestled with how to govern large and diverse populations while preserving individual liberties and promoting economic development. The unraveling of the United States in 1861 enabled Mexican Conservatives to entice an intervention by the French Empire of Napoleon III. Preoccupied by civil war, the Union could not enforce the Monroe Doctrine to stop Napoleon from imposing a monarchy on the ruins of the republic in Mexico. Confederates welcomed that French intervention in the hope that it would lead Britain and France to assist them against the Union blockade of southern ports. Meanwhile, Canadian leaders worried that the American conflict would spill over into an invasion of their provinces. That worry led them to create a larger confederation that would extend from the Atlantic to the Pacific—in the hope that greater unity could better secure them against American annexation.

The book is populated by a diverse cast of individuals, some of them (Abraham Lincoln, Frederick Douglass, Robert E. Lee) probably familiar to your readers, others (Emperor Maximilian, John A. Macdonald, Benito Juárez) perhaps less so. Of them all, is there one whose story you found especially important?

Maximilian was the Austrian archduke selected by Napoleon III and Mexican Conservatives to become the emperor of Mexico. They sought to overturn the Liberal republic led by Benito Juárez, who grew up as an Indian and then rose through education and merit to become president of Mexico. Juárez emerged (along with Lincoln) as the most compelling character of the 1860s in North America. Both were champions of liberalism, which promoted equal civil rights and economic opportunity for individuals. Lincoln and Juárez struggled to defend those rights and opportunities against the challenges posed by southern secession (in the United States) and Conservative monarchy (in Mexico). Juárez fought against even greater odds and came far closer to defeat than did Lincoln. Although short and slight, the Mexican president prevailed in his struggle through a force of will and a dignified conviction that impressed all who met him. Juárez strikes me as the most compelling character of that generation when considered on a continental scale.

Do Americans suffer from thinking our Civil War stands out in human history? Or is this the imprint of all civil wars on their countries?

The citizens of large and powerful countries focus on their own histories to the neglect of others. Nineteenth-century events also contributed to the fixation of Americans on their own destiny and their sense of withdrawal from external entanglements. By 1860, the defenders of the Union believed that they upheld the last best hope for free government in the world. During the preceding dozen years, European monarchies had crushed revolutions by liberals trying to establish republics. Thousands of liberal activists fled from Europe to become American citizens. That backdrop of defeats and exodus helps to explicate the passion with which so many American citizens, by birth and immigration, rallied in 1861 to defend the Union as the cause of global freedom. If the Union fell apart, they feared that free government would collapse—discrediting liberal values forever and consigning all of humanity to arbitrary government. Lincoln expressed this with concise brilliance in his Gettysburg Address. In Americans’ historical memory, the success of the struggle to restore the Union has tended to obscure the parallel stories playing out elsewhere in North America.

How would you describe your research process? What sources did you find particularly illuminating?

For a book covering this scale in time (24 years) and geography (a continent), a writer depends primarily on published scholarship by specialists dealing with parts of the bigger story. For the American aspects of the story, I especially benefited from the scholarship produced by my colleagues at the University of Virginia: Gary Gallagher, Caroline Janney, and Elizabeth Varon. I supplemented the scholarly sources with contemporary texts, such as the memoirs of Philip Sheridan and journalism by Jane Grey Swisshelm and Jane McManus Cazneau. The most useful of the published documentary collections included the papers of Ulysses S. Grant and the dispatches of Matías Romero (Mexico’s ambassador to the U.S.).

What if anything new did you learn about this critical period in American history?

I learned the utopian aspirations of 19th-century liberals, who imagined a far better world if all individuals could participate in their own governance and compete in a fair economy to get ahead. I also became more aware of the historical roots of the contemporary economic and political interdependence of Canada, the United States, Mexico, Cuba, and Santo Domingo (now the Dominican Republic). As citizens, we should recognize those ties in our present as well as the past.

Can you sum up in brief what you hope readers will take away from American Civil Wars?

I hope readers will rediscover the passionate commitment of most Americans to preserving their Union as indispensable to sustaining their free government and economic prosperity. The diverse unions (or confederations) of Canada, Mexico, and the United States were difficult to achieve and cost immense quantities of blood and treasure (in two of the countries) to preserve. We should mark down as reckless fools those who speak so carelessly about dissolving the Union as if membership could or should be voluntary for individual states.

What’s next for you? Any plans to focus again on the Civil War era?

I tend to alternate between broad, overview books, such as American Civil Wars, and more local studies that rely on primary sources. For my next project, I will focus on a Virginia family that owned plantations in Sussex and Southampton counties, the setting for Nat Turner’s revolt. That family left a treasure trove of documents largely untapped by historians. While that book will focus on the early republic through the 1830s, the subsequent fate of the plantations during the Civil War and Reconstruction will feature in the last chapter.