Kevin M. Levin discusses the nature of black men’s service in the Confederate military during the Civil War.

Transcript

Terry Johnston: Kevin, thanks so much for joining us today. Our question for you, which was submitted anonymously, is: “There’s been a lot of debate over whether any black men served in the Confederate army. Did they? If so, how many? And in what capacity?”

Kevin Levin: So thanks for the question, Terry. It’s great to be with you today. It’s a question that I get all the time. And, here’s how I would go about responding to this. At the very end of the war, after a very lengthy and very bitter debate that took place throughout the Confederacy—including within the army, in the Confederate Congress—on March 13, so mid-March 1865, the Confederate Congress barely passed legislation allowing black men to be enlisted as soldiers. This is the first time the Confederacy decides to do this. And so we know that within those last few weeks of the war, in places like Richmond, for example, we know that maybe two companies of black men were enlisted. They were housed in a prison. They may have marched a couple times down Broad Street. There’s no evidence to suggest that they were armed or even that they were given uniforms. And, of course, as we all know, the war ended before any of them could be moved to the field itself. So there’s no evidence that during those last few weeks, as Lee’s army is retreating toward Appomattox, for example, that these individuals were deployed. So the war ended for the Confederacy as it began.

And I should point out the war began for both the United States and the Confederacy as a war that would be fought by white men. Of course, as we all know, it’s not until 1863 that the United States begins to enlist black men in the army. And roughly 180,000 do so by 1865. So both the United States and the Confederacy followed very different trajectories between 1861 and 1865. For the Confederacy, however, from the very beginning of the war, they’re very much aware of the discrepancy when it comes to war materiel, various resources that would be needed for the war. And right there at the top of the list, of course, is just manpower, sheer manpower. The population of the North in 1861 is roughly 18 million; in the Confederacy, much of the South, we’re talking about a population in total around 9 million. And half are enslaved.

National Archives

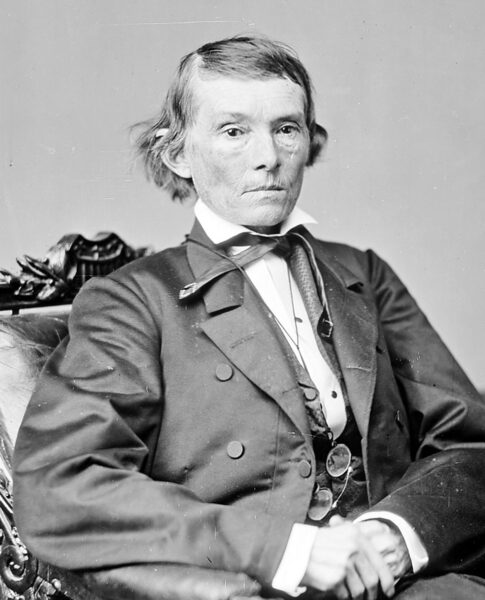

National ArchivesAlexander Stephens, vice president of the Confederacy

So the Confederacy has to figure out how to utilize its slave labor. And they do so in a number of ways. Enslaved labor is used to construct and maintain earthworks around various cities, to extend and repair rail lines, in factories in places like Tredegar in Richmond, in Atlanta, in Selma, Alabama, to produce the material needed to make war. And so, when Alexander Stevens talked about slavery being the cornerstone of the war, we can think about that in the context of the Confederacy’s attempt to make war itself and the role they played in allowing them to advance that. I should also point out that thousands of enslaved men will accompany their masters as what they would’ve called body servants, into the army itself. And they would’ve been there as an extension of their master. They were not an official part of Confederate military. They were there, of course, as legal extensions of their owners, of their enslavers.

And so throughout the war, the Confederacy maintains this very sharp distinction between enslaved laborers and maintaining the rank and file—the citizen soldier—as white. Again, that changes during the last few weeks of the war. And I should also point out—I think it’s a very reasonable question to ask—this is not so much a debate among scholars. This is a debate that has existed for a number of decades, going back to the late 1970s, early eighties, and then especially on the internet in the nineties and, of course, into the 2000s.

Terry Johnston: Well, look, you’ve just hit on a lot of interesting and important points that I think we should unpack. But going back to the original question, I guess it really fundamentally comes down to what we mean by the word “serve,” doesn’t it? So if by “service” you’re talking about black Confederates as uniformed soldiers carrying weapons and duly enlisted, no. If you’re talking about body servants or camp slaves, then yes, there was a significant—you tell me how significant—presence of those men in the Confederate armies, weren’t there?

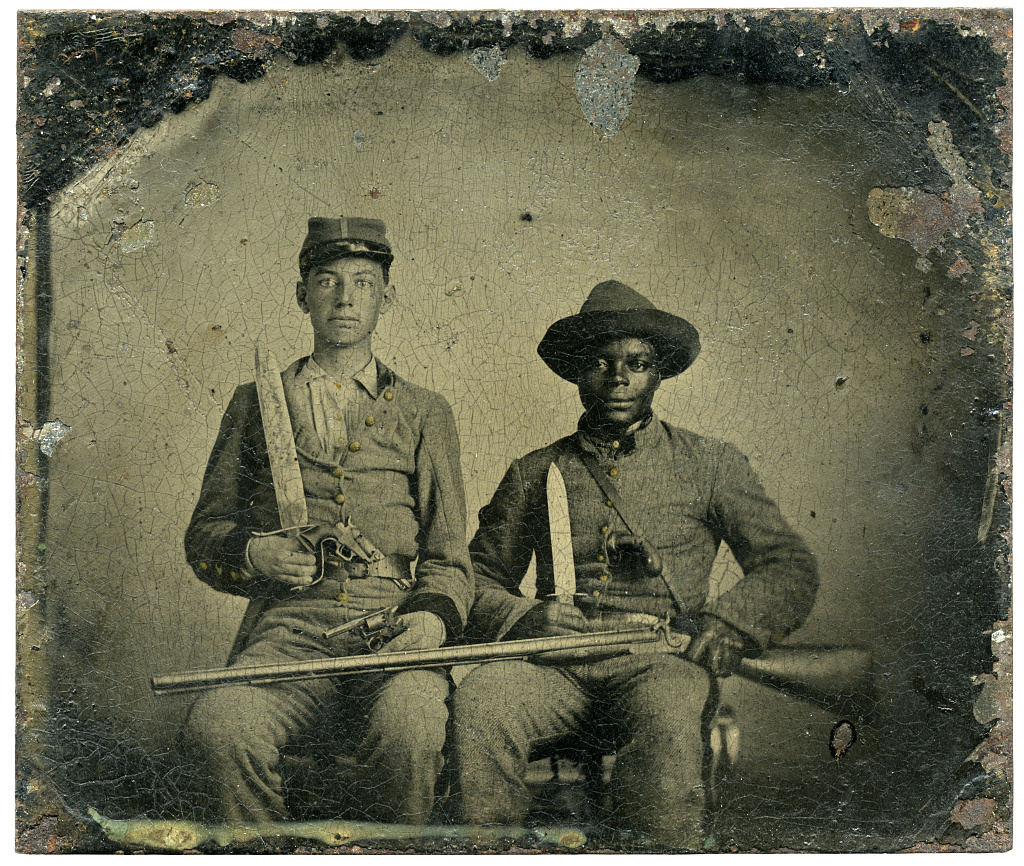

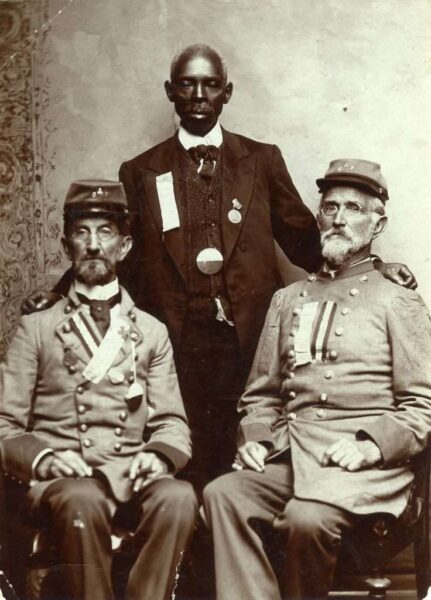

Kevin Levin: That’s right. And it can be confusing. Because of course you can go on the internet today and find, you know, a number of photographs of black men in uniforms and they’re posing alongside their enslavers. And, some people are confused by this and will conclude that because they’re in uniform they must have been enlisted as soldiers. But when we talk about serving in the context of body servants, they are there to serve their masters. They’re there to serve their enslavers. Again, they are not part of the military apparatus, if you will, of the Confederacy itself.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressSilas Chandler (right), an enslaved man, poses in Confederate uniform with Sergeant A.M. Chandler of the 44th Mississippi Infantry, who he accompanied to the front as a body servant.

And so those distinctions are really important. But make no mistake. If we’re just talking about, for example, Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, if we think about its movement into Maryland and Pennsylvania in the summer of 1863, culminating in the Battle of Gettysburg, there may have been upwards of 10,000 enslaved laborers with that army. And when you step back and you think about it from that perspective, that completely shifts how you think about the army itself and what it needs to do what armies have to do: camp, march, and of course engage in battle. And enslaved men are there every step of the way. The body servants, of course, are supporting their enslavers. There are people, enslaved laborers, who are performing the role of teamsters. They are hospital attendants. They are doing all kinds of support work that free up as many white men as possible. Because, again, it all comes back down to simply the need for men to shoulder rifles.

The other thing important to remember, and I think is often lost in this discussion, is that when we’re talking about soldiers and how we define soldiers in the context of the Civil War, the mid-19th century—and this would be true for the Confederacy and the United States—we are talking about the citizen soldier. We are talking about free men who have an obligation to serve their governments when they are needed. That is, in a sense, the trade-off in a republic. And so many, of course, volunteer early in the war. But both sides institute drafts at different points. And they are basically expected to serve for as long as they are needed, three years in the case of the United States, and, eventually, as long as the war extends for the Confederacy. And then after the war, they will be decommissioned and returned to their lives as citizens.

That’s the role they perform within their respective countries. And enslaved laborers simply don’t fit that mold. And that’s why the Confederate Congress at least has to take special action to make that happen.

Terry Johnston: Right. Well, let’s get into that. You mentioned the late-war debate over the arming of slaves that occurred among Confederate leadership. And it’s always struck me that the clearest piece of evidence against the existence of black Confederate soldiers is the fact that this debate actually happened. Why debate this if black men are already serving? So, can we talk a little bit about how this debate really came about? I normally hear Confederate General Patrick Cleburne’s name associated with it, he of the Army of Tennessee, in 1863. And then again, as you alluded to earlier, it really picks up, among the Confederate Congress even, in late 1864, early 1865. So what exactly were the proposals? What motivated them? What did that look like?

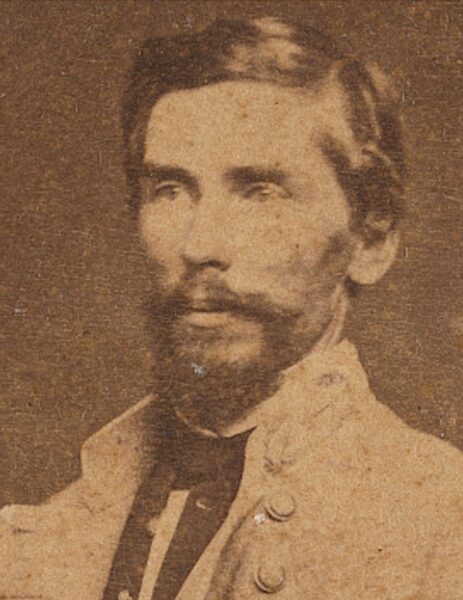

Library of Congress

Library of CongressConfederate general Patrick Cleburne

Kevin Levin: Yeah, and let’s keep in mind there are proposals going back all the way to 1861. Richard Stoddard Ewell, for example, proposes this in 1861 at one point. [Confederate president Jefferson] Davis is steadfast against this into the later part of 1864. In fact, when Cleburne first proposes this idea and word gets to Davis in Richmond, Davis orders Cleburne and his staff to cease discussing it. And so he’s obviously worried about morale.

I think Davis believed that this was a kind of corrosive idea. If the Confederacy is attempting to gain its independence, to become an independent slaveholding republic, this kind of talk undermines that. The issue becomes more practical for members of the Confederate Congress, and especially the Confederacy at large, once you get into the spring and summer of 1864. Because, of course, you’ve got Sherman moving on Atlanta, you’ve got Grant laying siege—or the closest thing to a siege—around Petersburg. And something has to give here. And more people are beginning to realize that perhaps defeat at the hands of the Yankees is worse than some kind of legislation that allows for black men to serve, but at the same time maintains the structure—the institution—of slavery. These proposals—let’s not be confused about this—these proposals were not general emancipation proposals. They were an attempt to salvage as much of slavery as possible.

For members of the Confederate Congress, if you look at their differing views on this issue, it’s interesting because those members that are from areas that have already directly been impacted by the Union army—and so the movement of the Union army is really important in all of this. So if you are from a state or a county that has already been overrun by the Yankees, you might be more willing to consider this as a proposal. If you’re from a place like Texas, however, you may take a more conservative approach to this. You’re not quite ready to give into something so radical.

And so you have this debate taking place in the Congress, in editorials throughout the Confederacy, and even in the army itself. And so, regiments, for example, in the Army of Northern Virginia and other armies, they are voting on this issue. And in some cases they are publicizing the results. And, it’s difficult to gauge where the armies are in all of this. You’ll find differing opinions. But I think one thing is clear, that even for those people who vote for it or support this policy, they haven’t shifted their understanding of race and slavery. This is an attempt to avoid the worst calamity, which would be defeat.

And again, I think that has something in common with what you find in the United States. For if we’re thinking about the mobilization of black men into regiments in the United States, there are a lot of people who support it because, look, we need more men. And so it’s a practical consideration in large part in both nations.

Terry Johnston: It does seem that there are similarities. It’s almost like the Confederacy’s having the debate that the Union had two, three years earlier.

Kevin Levin: Exactly.

Terry Johnston: I have a quote, I think it was from the governor of Georgia, that’s stuck in my mind: “When we arm the slaves, we abandon slavery.” That even then, there were these folks—again, this is the governor of Georgia, and as you’ve mentioned, Sherman’s March has already cut a swath of destruction through the state, and even then, forget about it, right? And it’s the idea black men can’t be trusted as soldiers. We can’t arm these folks. And that was something that you saw early on in the Union debate about creating black regiments too.

Kevin Levin: That’s absolutely right. And it also, I mean, let’s not forget the moments on the battlefield in places like Virginia where Lee’s men are coming into contact for the first time with uniformed and armed United States Colored Troops. Think about a place like the Crater, where these men are massacred in significant numbers. And when you read the letters and diaries from Confederates in the days and weeks after that battle, they see themselves as putting down a slave rebellion. They see an armed black man and they immediately imagine Nat Turner, right? Or something as horrific as Nat Turner and on a much larger scale now. So, when we’re trying to understand why Confederates are so divided over this, it’s because the idea of arming black men, it conjures up a very difficult history, right? The history of slave rebellion.

Terry Johnston: Right. Well, so getting back to the actual proposal that eventually passed the Congress, what were the terms? As you said, we’re not on the path to overturning the institution of slavery. That’s not going to happen. But what were they willing to give these enslaved men in exchange for their service?

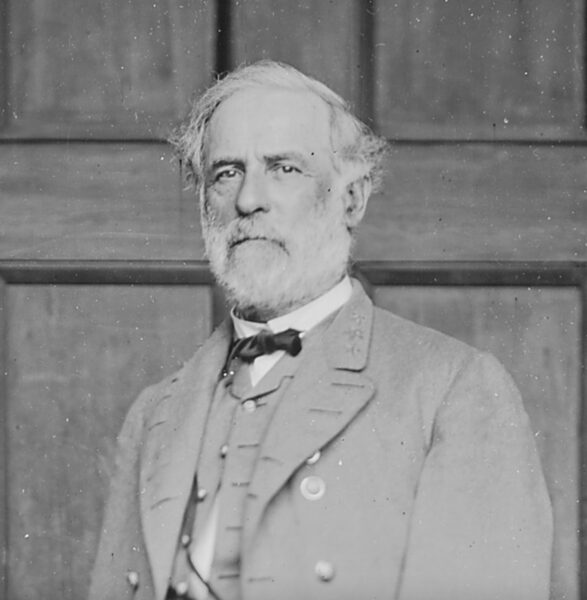

National Archives

National ArchivesRobert E. Lee

Kevin Levin: So the big debate over this is whether or not they need to be freed for service. And, if I remember correctly, I think it’s Robert E. Lee himself who says, you have to free these men first. Which of course is a tough pill to swallow because one of the major cultural assumptions behind slavery is that slavery is a benign system. White southerners, slaveowners believe that they are benevolent slave owners, right? That they are caring for these men, women, and children. That they’re a part of their families.

And so, why do they need to be freed? So that actually is the big sticking point when it comes to the details of the policy. And in the end, they come to the realization that these men have to first be freed or else why do they have any interest in fighting? Their motivation simply wouldn’t be there. But that gives up quite a bit. That gives up quite a bit. And for some, just too much to stomach. So that’s really, for me, that’s the central issue in the debate. There are other issues, but they’re not as serious. This one is the core issue.

Terry Johnston: Yeah. Well, getting back to another thing that you mentioned earlier about just the concept of black Confederates. That is a postwar phenomenon in large part, isn’t it? how does that come about? How does this evolve? And how does it get us to where we are now in the use and thinking of that term?

Kevin Levin: Yeah. That phrase “black Confederate” is rarely used during the war or during the postwar period. I was able to track it using a number of digital tools and it really—I wasn’t surprised by the time I did this, given my research—but it really comes into popular use in the 1970s as Confederate heritage organizations are attempting to essentially rewrite the history, attempting to counter what you might describe as a more emancipationist narrative of the Civil War where slavery is discussed, where black military service is acknowledged. But you don’t find it during the war, during the postwar period.

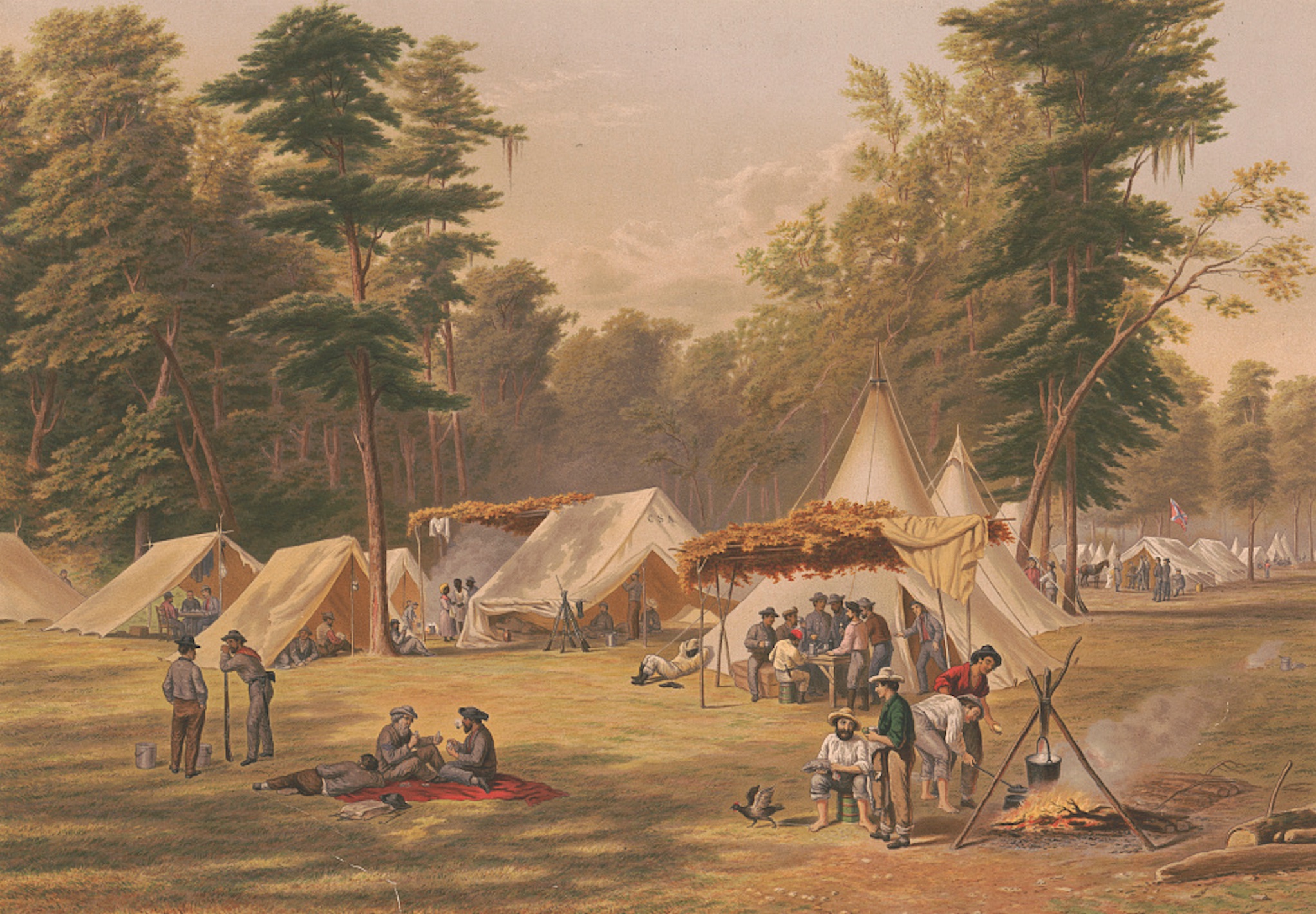

For the generation that experienced the war, especially for the soldiers—and again, remember, if you’ve got roughly 10,000 of these men present in the Army of Northern Virginia, that means that these soldiers are surrounded by these men. They see them throughout the day. They see them in every context of the military itself: in camp, on the march, on the battlefield even. But they’re not confused as to the status of these men. And so, when they’re writing their postwar memoirs, writing for newspapers, for Confederate Veteran, they are writing about the loyal body servants. This is a narrative that would’ve been an extension of the loyal slave narrative from the antebellum period.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressThis 1871 chromolithograph, based on a painting by former Confederate soldier C.W. Chapman, depicts enslaved men and women among uniformed soldiers in a Confederate army camp.

So in that sense, they’re very consistent. I think real Confederates would be quite surprised and shocked by the way in which their so-called modern-day defenders talk about these men. When we’re talking about Confederate veterans’ reunions, former body servants sometimes attend in significant numbers. They march with the veterans. I think they do so for any number of reasons. There may have been financial kinds of considerations. I know one individual who would entertain large crowds. My guess is that, perhaps through tips, other kinds of payments, he may have made some money through this. But again, the generation that experienced the war and generations after the war understood that they were talking about formerly enslaved men.

And you see this on, for example, the Confederate monument in Arlington National Cemetery that was removed in 2023. When you look at the images around that monument, you will see the image of the loyal mammy taking the child of the Confederate officer—a very clear image of slave loyalty. And then the black man marching off to war with the Confederates, he’s in uniform as well. And if you read the UDC’s [United Daughters of the Confederacy’s] handbook or program describing this monument, they describe him as a loyal body servant, essentially. And so it’s quite striking when you think about the shift that takes place in how these men are remembered much later. Much, much later.

Terry Johnston: Right. And that shift, the folks who advocate for that point of view, some of the evidence they use is easily debunked. I know one is—and I know you’ve gotten into this a big deal, maybe you can discuss it some now—pension records, that there were body servants who actually received Confederate pensions. And that can be a confusing thing.

Encyclopedia Virginia

Encyclopedia VirginiaTwo Confederate veterans pose with a black man—presumably a former body servant—in a postwar image.

Kevin Levin: I think it’s five or six former Confederate states. Mississippi is the first in the late 1870s, and then the rest in the 1920s. And, of course, by then we’re talking about relatively few people who are even alive to take advantage of this. The payment they received was not the same, of course, as a Confederate soldier. Remember, there are no pensions from the federal government, so they have to rely on the good graces of their respective states. But these formerly enslaved men would have filled out a form—most states utilized a special form for former body servants—and they would have to list things like their enslaver, where they were during the war. In most of these applications, there was also room to describe your experience. And it was always interesting—not every applicant took advantage of this, but it was always interesting to read their attempt to both capture their own sense of adventure, their own individual experience of the war, and also try to deliver what they believed the pension examiners would have wanted to read. And that, of course, would’ve been a decidedly Lost Cause narrative, where you constantly see references to people like Robert E. Lee. It seems like every body servant that existed worked for Robert E. Lee at some point, right? You get the point.

Terry Johnston: Yeah. Well, so then fast forwarding to today, if the idea of black Confederate soldiers is a modern phenomenon, where do we stand in 2025? Is that belief as prevalent as ever? Has it waned some? Where do we stand now in the thinking about black Confederates?

Kevin Levin: It’s hard to say. I wouldn’t even really know how to go about measuring it. I guess anecdotally it does seem as though it’s died down a bit. I mean, I certainly don’t want to claim any credit for that. I think I understand the reach of books these days and who reads them and who doesn’t. I think it’s certainly still a popular narrative among the Confederate heritage community. And so if you were to survey the social media platforms of, for example, the Sons of Confederate Veterans and other groups, you will still find that being bandied about.

But I don’t get the sense, I mean, the kinds of news stories that I remember 10, 12 years ago—textbooks in Virginia including references to black Confederates and, even more recently in 2017, two Republican state senators in South Carolina wanted to propose a monument to the loyal black Confederate soldier for the State House grounds in Columbia. And that immediately got shot down. So those kinds of attempts, those more high-profile stories that used to appear in the mainstream news, I don’t see much of that at all. And I guess that’s a good thing.

Terry Johnston: Well, and maybe it coincides in some way to the post-Confederate flag debate.

Kevin Levin: Yeah, it’s possible. You might be right about that. My own interest in this, I’m working on a book about the Battle of Gettysburg from the perspective of what you might call the body servant community, so I want to understand how the presence of enslaved men in an army like the Army of Northern Virginia during a specific campaign impact the ebb and flow of that battle. No one’s really done that before. But there are other aspects, you know, it always disappointed me, I’m always so saddened whenever I had to deal with this debate, because it seems to me—and it’s always seemed to me to be the case—that there are really interesting questions that historians and students of history can explore. And one of the things that I struggled quite a bit with during my research is just trying to really understand that master-slave dynamic in the army. Here you have an environment that very few people could have anticipated before 1861. We think about the master-slave relationship in the context of the homefront, plantation life, etc. But what happens when you pluck that relationship out of that familiar landscape and place it into something new? And so, one of the questions that I’m still struggling with is how did the reality of war and the demands of war impact that relationship? And how did master and slave see one another within this new world, this new environment?

And that’s something I’m really trying to get at with this new project. And it’s really difficult because we really only have the records of the officers, Confederate officers, and the few enlisted men who brought body servants with them. We don’t have much from the enslaved themselves. And so, you have to be very careful when you’re doing this work. But there are so many interesting questions to explore surrounding how the Confederacy conducted war as a slave-based economy.

Terry Johnston: Yeah, you’re right. Because we do have quite a bit from Confederate officers in the way of wartime letters and diaries, but what about the body servants that accompanied them? I suppose the postwar evidence that you were alluding to earlier, you had to really navigate that carefully for a variety of reasons. So, wrapping this up, is there anything important that you think we’ve left unsaid about the issue?

Kevin Levin: Yeah, I guess I would just follow up my last point. One of the most common debates among students of the Civil War is what did these men fight for? Were they fighting for slavery? And that usually involves looking at letters, looking at diaries, trying to find the evidence, the language, the words. And I think that question has really been played out. And I’m trying to reframe this question about ideology and this question about the place of slavery in the life of the common soldier, the rank and file, by moving away from that question. Instead of asking, what did they fight for? Were they fighting for slavery? I think what we should be asking is, how did the rank and file, how did the common soldier experience slavery while they were in the army? And again, if we think about the kinds of numbers that I’ve referenced during our conversation today, we have to imagine that these men were surrounded by enslaved men. That means both slaveowners and non-slaveowners alike.

And so even for non-slaveowners, they may have been part of a company mess where one soldier had a body servant with them, and that means all of them benefited from their labor. It means that a non-slaveowner could perhaps rent a slave, an enslaved man, to perform some kind of job while they’re in camp for an extended period of time. But it also means that they are reminded of the place of slavery within the broader society. They’re constantly reminded of this. And so I think by refocusing the question itself, it might help us better understand how these men are not just thinking about this question, including the question of motivation, but also just more generally how they’re experiencing it on a day-to-day basis.

About the Guest

Kevin M. Levin is a historian and educator based in Boston. He is the author of numerous books and articles on the Civil War, including Searching for Black Confederates: The Civil War’s Most Persistent Myth (UNC Press, 2019). He is currently completing a biography of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw.

Kevin M. Levin is a historian and educator based in Boston. He is the author of numerous books and articles on the Civil War, including Searching for Black Confederates: The Civil War’s Most Persistent Myth (UNC Press, 2019). He is currently completing a biography of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw.

Additional Resources

- Confederate Congress authorizes arming slaves as soldiers

- Battle of the Crater

- Confederate Memorial at Arlington National Cemetery

- Two South Carolina legislators propose monument for black Confederates