Historian Jonathan S. Jones discusses the causes and prevalence of postwar drug addiction among Union and Confederate veterans.

Transcript

Terry Johnston: Jonathan, thanks very much for joining me today. Our question for you is from Jeff in Louisiana. He asks, “Are there statistics showing the rates of postwar drug addiction for Union and Confederate soldiers who were administered morphine or similar opiates during the conflict?”

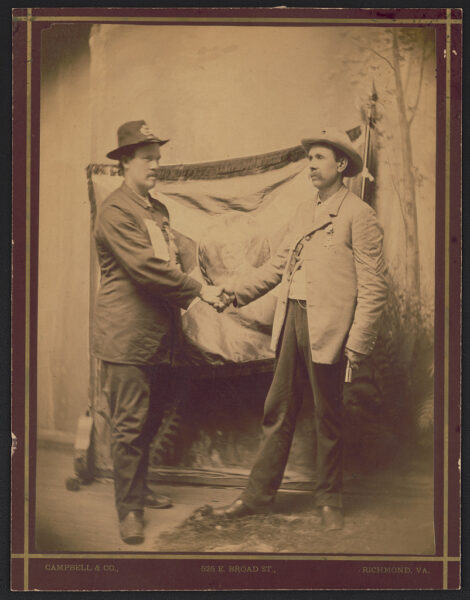

Library of Congress

Library of CongressTwo Civil War veterans—one Union, one Confederate—shake hands for the camera in a postwar photo.

Jonathan Jones: That’s a great question, and a problem that I think has both been really interesting for historians for a long time and also increasingly relevant as we learn more about Civil War veterans, but also in the context of today’s opioid crisis. The short answer is that we don’t know exactly how many Civil War veterans became addicted to opiates. But, as we can imagine, knowing what we know about the carnage of the war, it’s safe to assume that addiction was pretty widespread and that probably thousands of veterans became addicted.

Terry Johnston: Yeah, and the population of veterans themselves is really sizable. Just by the rough math, you see statistics where there were some 2.75, give or take, million men who served in the Union and Confederate armies. Anywhere from 600,000 to three-quarters of a million died either because of combat or wounds or disease. And so, you’ve got circa 2 million men at war’s end going home. So this is a big population of veterans, right?

Jonathan Jones: Absolutely, yeah. And they represented a medical microcosm of the rest of the country. And they had their own unique ailments. These are folks that we could reasonably expect to have taken morphine or been exposed to opium. And considering that these are addictive substances, it’s likely that many of these folks—somewhere in the thousands—did become addicted.

Terry Johnston: Well let’s back up and talk some about the drugs themselves and how these men were exposed to them during the war. What opiates were they administered? How often? For what reasons? Fill us in.

Jonathan Jones: Absolutely. So opiates were extremely widespread all throughout the 19th century. They were among the most popular drugs in America before, during, and after the Civil War. So they were basically ubiquitous. They were popular really for two reasons. They are painkillers and really effective ones at that. And we know that the Civil War is full of pain and physical suffering. They were also popular as antidiarrheals. And I think we don’t often remember this, kind of thinking in hindsight from our society, which is relatively kind of sanitary, but the Civil War is an environment that’s teaming with microbes and different ways for you to become sick. And so diarrhea was a pervasive problem for Civil War soldiers and veterans.

And so for those two reasons—painkilling properties and antidiarrheal properties—opium, morphine, including injectable morphine, and a liquid version of opiates called laudanum, which is basically opium mixed with alcohol (you can imagine the punch that that would pack), these are really popular and widely used drugs. Actually, the Confederate military put this really plainly in a surgical handbook. It described opium as being as important to the surgeon as gunpowder is to the ordnance. And I think that kind of martial metaphor would’ve made sense to people during the Civil War.

Terry Johnston: Yeah. And morphine injections in particular, weren’t they considered almost cutting-edge medical technology at the time? Was that a new development or just something that was used differently?

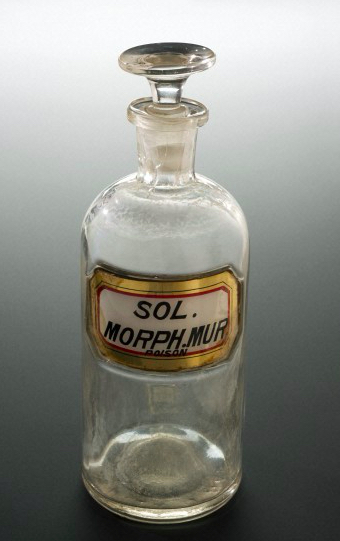

Science Museum, London

Science Museum, LondonA morphine bottle produced during the Civil War era

Jonathan Jones: Yeah, this was the tip of the spear for military surgeons during the Civil War, especially in the Union Medical Corps, where they had more consistent access to morphine and the ability to get some of these kind of cutting-edge new medical devices like the early versions of the hypodermic syringe. These are devices that had been invented in the early and mid-1800s in Europe, where European physicians had learned to use them in medical school and they were a lot more commonplace. In the U.S., it wasn’t really until the Civil War that American doctors and surgeons had a real, or at least realized a need to use these devices. Union army surgeons—like better educated, better prepared surgeons—when they volunteered to join the Union Medical Corps, some of them brought hypodermic syringes, like privately owned syringes, with them. And they showed their fellow surgeons how to draw up the proper amount of morphine, where to use the needle to inject it for the most effect. And the practice took off like wildfire. So after the Civil War, the hypodermic syringe continues to become incredibly popular. And the wartime use in hospitals was one of the reasons for that.

Terry Johnston: Well, about that wartime use. So you’re a soldier either who’s just had an amputation, or you’re suffering from diarrhea or dysentery, and you’re legitimately getting some sort of opioid as treatment. But what does that look like? How much are you getting? Are these doctors, in hindsight, just prescribing it too liberally? How quickly are these soldiers getting hooked?

Jonathan Jones: Yeah, great question. So, in the 19th century, doctors are still working out some of the basics that we know about addiction. Going into the Civil War, there’s the realization that opiates are habit forming. Civil War Americans lacked the clear, really heavily medicalized language that we have available to us. So the word addiction was less common back then than it is today. But they had 19th century ways of expressing this concept of dependency to opiates. Oftentimes, for example, they called addiction a kind of slavery.

So there’s this recognition that this is a potential outcome of opiate use. But doctors don’t know how long it takes. They don’t know why some folks seem to develop so-called slavery to opium while others are able to have morphine in a hospital and not develop a compulsion to use it. And so they start to develop early theories about addiction. Some of the doctors theorized that a person who might be physically weaker was more prone to developing addiction. And some of those ideas stem back to 19th-century beliefs about how men should behave, kind of stoically in the face of pain.

Terry Johnston: Is the main, or even only, way these soldiers have access to these drugs during the war through doctors? Or is there already becoming a black market for them?

Jonathan Jones: Yeah. So much that we know about opiates in our society, the existence that we have today where these narcotics are really heavily regulated, would’ve been totally unfamiliar to the Civil War generation. These are drugs that are available over the counter throughout the 19th century. There are very, very few, if any, regulations on opium or morphine in particular. So, for example, after the Civil War, $1.50 could buy a vial of morphine and two hypodermic syringes from Sears and Roebuck. And they would come to you in the mail, no prescription needed. And so really Civil War hospitals are like an entry point to these substances for a lot of soldiers. But there were many other ways to get them as well. And one did not need a prescription to obtain opiates at all really.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressUnion soldiers convalesce in a ward of Harewood Hospital in Washington, D.C.

Terry Johnston: Wow. So the supply was just steadily there during and after the war? Is it easier or harder in the postwar years to come by these drugs? Or is it pretty consistently available?

Jonathan Jones: Yeah, it actually gets easier. And we have a good sense of this. We know that opiates in the 19th century were mostly imported. Opium itself comes from the opium poppy, which is grown all around the world. And people try to grow it a little bit in the United States, but it never really takes off during the Civil War era. And so, the vast majority of opium coming into the United States was imported. And considering that there was a tariff on opium, we have relatively good statistics about how much opium is floating around the United States during this era. And so we know that, starting in the 1860s, going through the seventies, the eighties, even into the 1890s, opium imports skyrocket. And we know that from gauging tariff returns, of calculating out how much opium a person might need if they were addicted.

And so, this gives us really the best, but still rough, answer to the question that was asked about how many veterans became addicted. Using those tariff returns, we know, according to math that was done by historian David Courtwright, that in about 1840, when the tariff really kicks in, roughly 0.72 Americans per 1,000 Americans would’ve been addicted to these substances. If we follow the escalating importation of opiates and we continue to do the math, accounting for things like population growth, etc., we can see that, again, moving through the sixties, the seventies, into the 1880s and nineties, that enough opium is flowing by the year 1890 into American ports to sustain a much larger population of addicted Americans.

So we go from 0.72 out of a thousand in the 1840s to roughly 4.5 per 1,000 Americans in 1890. So that’s potentially a fivefold increase in the addiction rate. And again, to throw more numbers out there for the purpose of illustration, that would be, in 1890, roughly 313,000 Americans who are addicted to medicinal opiates, including both Civil War veterans and non-veterans. It’s a lot of people.

Terry Johnston: So it’s clearly out in the open. Wow. That is a lot of people.

Jonathan Jones: Yeah.

Terry Johnston: Well, you’ve written about how this post-Civil War opioid crisis was covered widely in the press. What did that coverage look like?

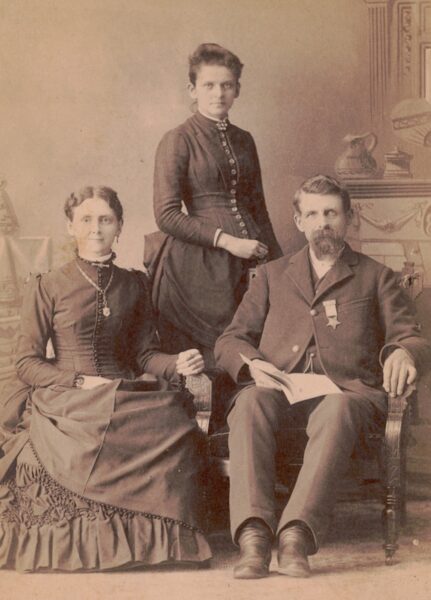

Library of Congress

Library of CongressAn unidentified Civil War veteran and his family

Jonathan Jones: Yeah, there was a panic about it. As the tariffs, for example, marked this extreme increase in opium imports, newspapers noticed. But it also didn’t have to take a really detailed look at the tariff returns every year to pick up on this trend. Families of Civil War veterans realized when wounded men came home that they were in pain, that they oftentimes were using opium or morphine really heavily, and that some of them had become addicted. And so, from a variety of vantage points, this appeared to be a major problem in American society.

The problem crescendoed, like I said a moment ago, into a kind of cultural panic about addiction. There were novels about addicted Civil War veterans. And, according to the plot of these novels, addiction ruined their lives and led to their downfall. So stories are told about the problem. There were newspaper exposes and even medical studies and books written about the phenomenon, all universally painting a pretty negative picture of addiction among veterans and other people as well.

I think the most interesting and alarming, from Civil War veterans’ point of view, consequence of this cultural panic over addiction was the fact that if Civil War veterans, like Union veterans, for example, went to apply for a pension for their military service or to try to secure room and board and medical care in a state-funded soldiers’ home facility or a federal funded facility, their addiction could get them kicked out of those facilities and their pension applications would get rejected. So there were a lot of really lived, negative consequences of addiction.

Terry Johnston: Well, moreover, and I think you’ve written about this, this segment of veterans, these veterans who were dealing with addiction, they weren’t always really viewed compassionately, whether by the press or the public. Compassion had its limits, didn’t it?

Jonathan Jones: Absolutely. Yeah. So we live in a society where, generally speaking, most American war veterans are not looked at negatively, right? So they’re looked at as relatively positive, deserving of support after they leave the military. And that is not necessarily the case after the Civil War. It is true that the government does operate a pension system. It’s true that there are people who are calling for charity. And Civil War veterans themselves demand entitlements to pay them back for their sacrifices.

But there were a lot of Americans in the postwar era that did not believe that military service, and even injuries during the war, should entitle veterans to government assistance or charity. Especially so for veterans that struggled with taboo issues like addiction to opiates or even to alcohol. And so, like you said, a lot of addicted veterans were dismissed in the press. Some ended up being jailed by local authorities who saw this phenomenon of addiction as potentially leading to crime. And so there were some really, really nasty outcomes for a lot of folks.

Terry Johnston: Well, what about treatment? What options were there for veterans suffering from addiction?

Jonathan Jones: That’s a great question. Considering the negative consequences that addiction could have in Civil War veterans’ lives, they were often pretty desperate to find some kind of a solution to addiction. And so a lot of veterans pursued the early version of rehab that we have today in the United States. These drug addiction treatment clinics started to pop up around the country in the 1870s and 1880s. When a veteran went there, they had to pay, right? So this is really only available to like middle- and upper-class veterans. You might stay for a month, you might stay for two months. Gradually, you would receive a smaller and smaller dose of opium or morphine every day, even multiple times a day, until eventually the idea was that you would be tapered off and you would be able to be released without needing to use morphine every day.

That may have worked in some cases, wasn’t always effective in other cases. Again, they don’t know a whole lot about addiction that we are lucky enough to know today. And so, cravings happened, people relapsed, and there weren’t good medical explanations for those outcomes. And so when that occurred, when a veteran got treatment, looked like they had successfully broken their so-called habit, and then relapsed a year or a couple of years down the road, people treated them really condescendingly, like they had failed somehow as men. There were also—I’m really fascinated by the unregulated nature of medicine back then—there were all kinds of snake oil, alleged cures for addiction that you could purchase through the mail, you could buy over the counter in a pharmacy. It was big. The Civil War addiction cure industry was big business.

Terry Johnston: And some of those miracle cures pedaled by the hucksters, they actually contained opiates, didn’t they, ironically enough?

Jonathan Jones: Yeah. This is like a wild twist in the story, right? So there’s no regulation that says that medicines have to disclose their ingredients back then. And so what a lot of medical salesman or entrepreneurs or shady folks, depending on how we want to look at it, what they realized is that they could keep their customers coming back for more and more and more vials of these supposed cures by putting morphine and opium in them and just not telling their customers. And so there’s a lot of that going on. It’s a real tragic story for a lot of folks who are desperate to get their problem, their perceived problem, under control, but there’s not really good ways to do that. And they end up getting scammed in the process.

Terry Johnston: So those clinics you alluded to earlier, what kind of access was there to your average veteran? Were they expensive? Exclusive? Or did your average veteran have a chance of—if they were so inclined—getting into one?

Jonathan Jones: Yeah, they were really hard to get. They were very exclusive. Part of that was the price point, which could run into the hundreds of dollars a month. That’s far beyond the average pension that Civil War veterans are getting in the Gilded Age. The majority of Civil War veterans simply couldn’t afford to seek care at one of these clinics. The clinics were also really exclusive about who they would admit. So even if a person had the funds to be able to afford to stop working and to go and stay in one of these clinics for a couple of months at the tune of a hundred dollars or so a month, that doesn’t necessarily mean that the doctors operating the clinic were willing to treat them. They had to pass, like, a morality screening. They had to be likable. And all of those were difficult for men who were struggling with a problem that was seen as taboo.

Terry Johnston: Yeah. Well, I wonder too, speaking of stories, I’m sure you’ve come across so many over the course of your research into the subject, both of the terrible tragedies of what addiction does to folks and maybe even success stories in getting past an addiction. Are there any particular stories that stick out in your mind that you could share about soldiers grappling with this issue?

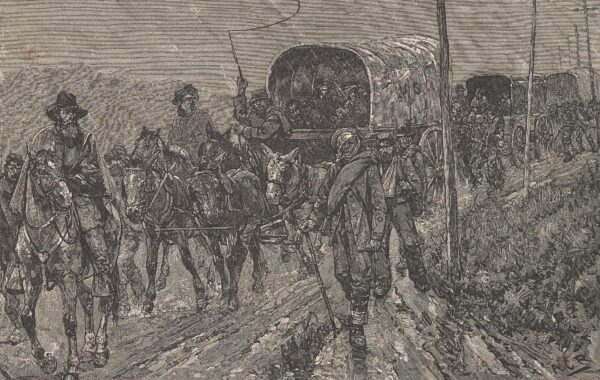

The New York Public Library Digital Collections

The New York Public Library Digital CollectionsThis 1881 illustration by Allen Christian Redwood depicts Confederate wounded being transported south after the Battle of Gettysburg.

Jonathan Jones: Absolutely. Yeah. The one that always comes back to me is a guy who fought at the Battle of Gettysburg, a Confederate soldier called Alpheus Chapel, a Virginian who helped to lead a company in Pickett’s Charge, where he’s wounded and transported back through Maryland and Pennsylvania, back to Virginia, to treat his gunshot wound. So he receives morphine from Confederate surgeons and predictably gets addicted to the drug. He had been a farmer before the Civil War, so he attempts to resume his occupation after the war. He finds that his old war wound keeps flaring up. So between the really painful war wound that limits his mobility and the addiction, he loses income. He is not able to even secure enough money to pay for the morphine that he’s addicted to.

I discovered this story by locating a letter where he is asking another Confederate veteran to supply him with funds so that he can afford the morphine that he can’t stop using. And so for me, the language that this guy uses, he really struggles to articulate his needs. He writes in this letter from the 1880s that he “can’t stop taking morphine.” And I think that that’s such a powerful and poignant way that he attempted to express what he was going through. So that’s always stuck with me.

Terry Johnston: Do we know the rest of that story and how it turns out for him ultimately?

Jonathan Jones: I wish. And this is one of the things that limits historians’ view of the opioid crisis after the Civil War more broadly, the record keeping is really very spotty. And so we don’t know what ended up happening to Alpheus Chapel. He may have been able to find a sympathetic ear. He may have been able to find treatment. Or it’s entirely possible that he continued to struggle with addiction for the rest of his life. Many Civil War veterans also fatally overdosed, and so this was a pretty common and pretty tragic outcome.

Terry Johnston: Yeah. Well, this has been wonderful. I wonder though, Jonathan, if you have any final words on the subject, something that we may not have covered completely?

Jonathan Jones: Actually, yeah. I think that if we take this story of the post-Civil War opiate addiction crisis and zoom out to a global lens that we would also find similar crises in other countries. There are, for example, reports in American medical journals of German veterans and French veterans of wars fought between Germany and France in the 1870s that report similar stories and similar outcomes with addiction that are really parallel to the stories of American Civil War veterans. There’s something about the emergence of the kind of warfare that people fight in the mid and late 19th century, coupled with the rise of these substances and new ways to use them, that dovetailed into each other and created this broad addiction crisis around the world. So I would love to learn more about this from a global perspective.

About the Guest

Jonathan S. Jones is an assistant professor of history at James Madison University whose scholarship investigates the aftershocks of the Civil War in American society, culture, and medicine. His first book, Opium Slavery: Civil War Veterans and America’s First Opioid Crisis, is forthcoming from the University of North Carolina Press.

Jonathan S. Jones is an assistant professor of history at James Madison University whose scholarship investigates the aftershocks of the Civil War in American society, culture, and medicine. His first book, Opium Slavery: Civil War Veterans and America’s First Opioid Crisis, is forthcoming from the University of North Carolina Press.

Additional Resources

- Jonathan S. Jones, “The Civil War’s Miracle Drugs”

- Historian David Courtwright