The summer of 1863 saw Lower Manhattan engulfed in turmoil, starting in mid-July. This unrest, a direct response to the implementation of a military draft law, occurred just days after Union forces celebrated their victory at Gettysburg. The participants in these riots were largely white, working-class immigrants who aligned with the anti-war Democrats. Their anger targeted public infrastructure, Protestant churches, the homes of those supporting the war or abolition, and, most tragically, the city’s African-American population, many of whom were murdered during the upheaval. The deployment of Union troops, some recently returned from Gettysburg, was eventually successful in quelling the violence. The riots left a devastating toll, with thousands injured and hundreds dead across New York City. Shown here are illustrations made at the time that depict the violence—and take its perpetrators, and supporters, to task.

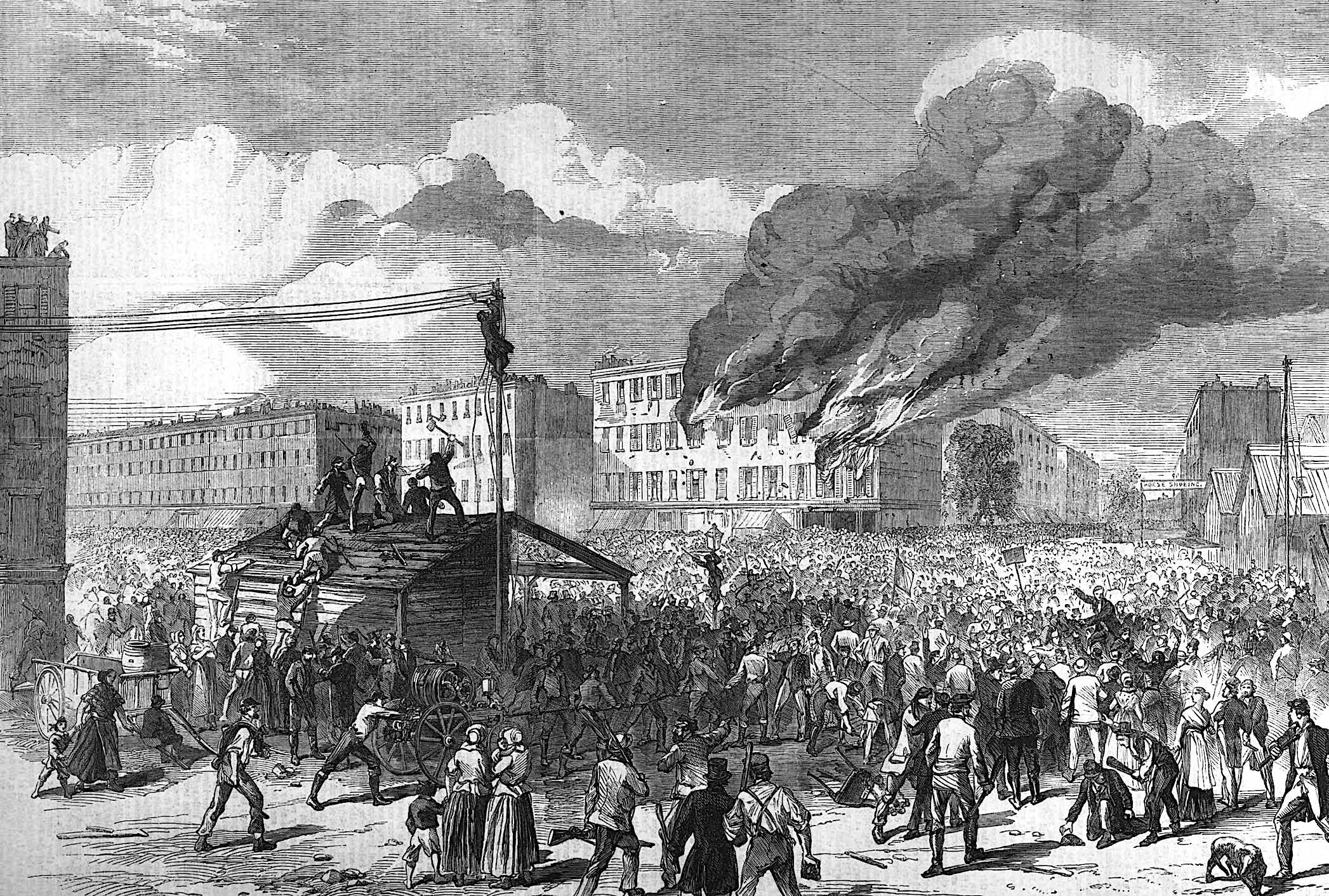

The burning of the provost marshal’s office by a mob of rioters is the subject of this detailed illustration from the August 8, 1863, issue of The Illustrated London News.

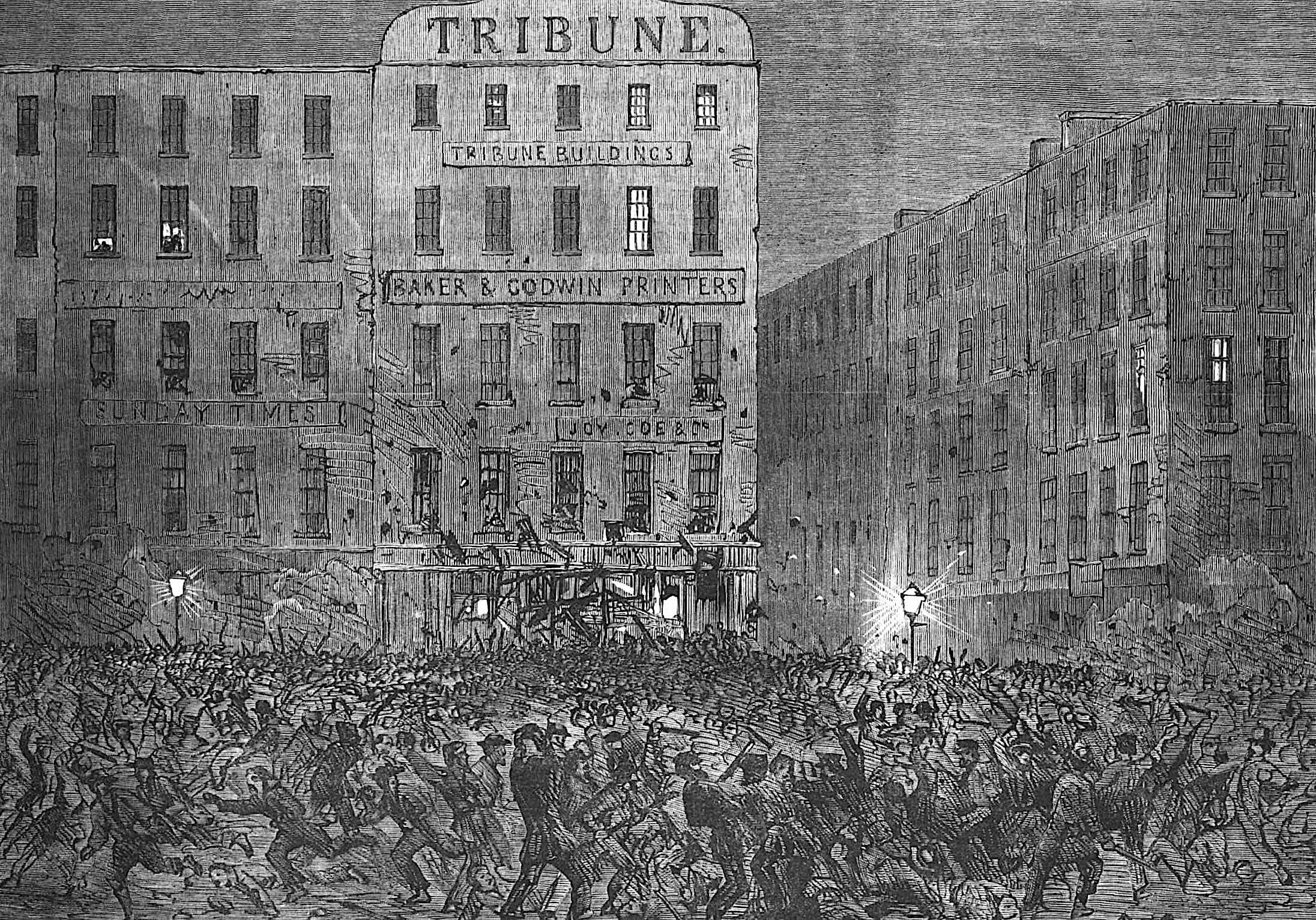

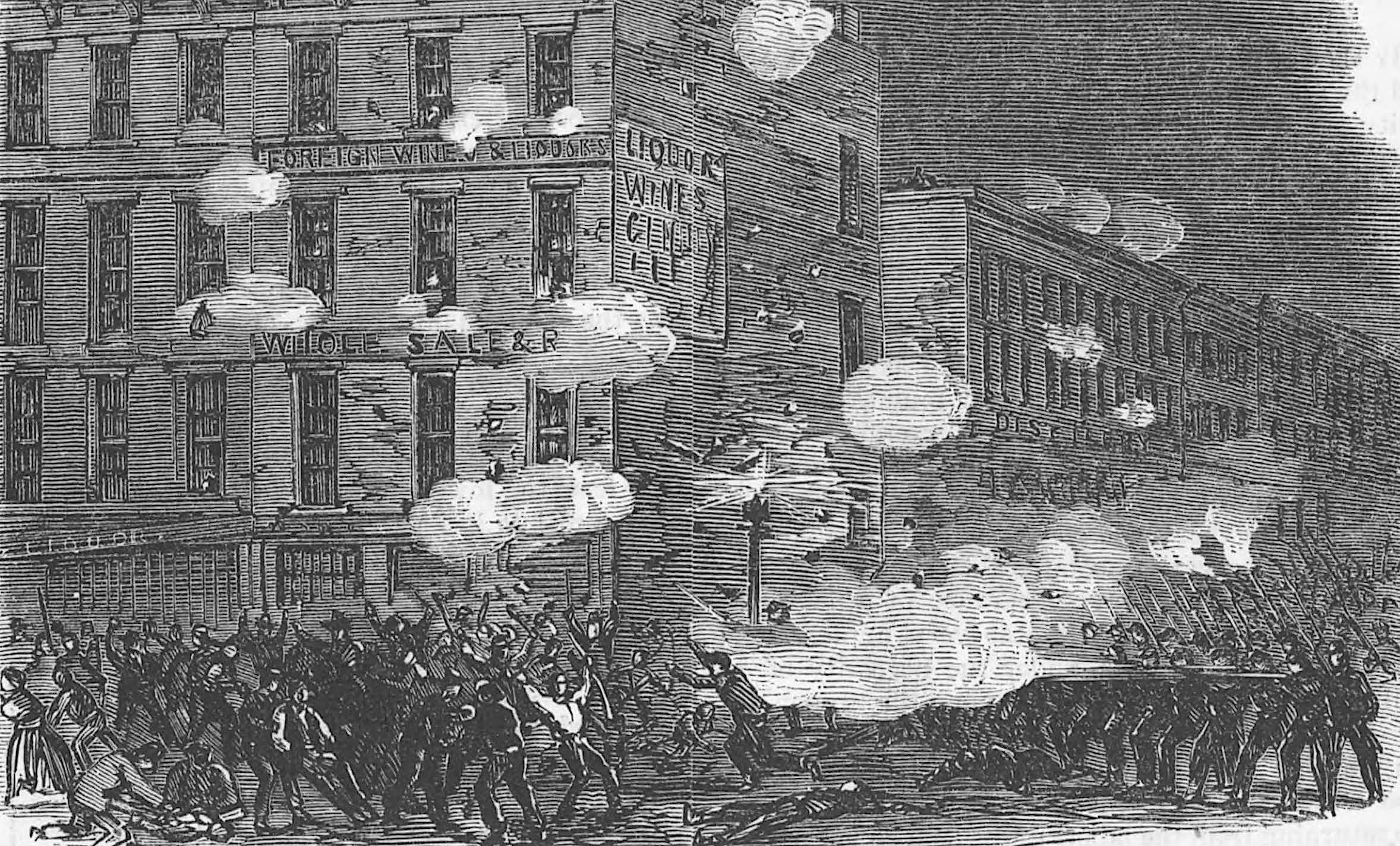

The Illustrated London News also printed this illustration of the chaotic scene outside offices of the New York Tribune, which rioters attacked for its editorial support of the war effort—and the draft.

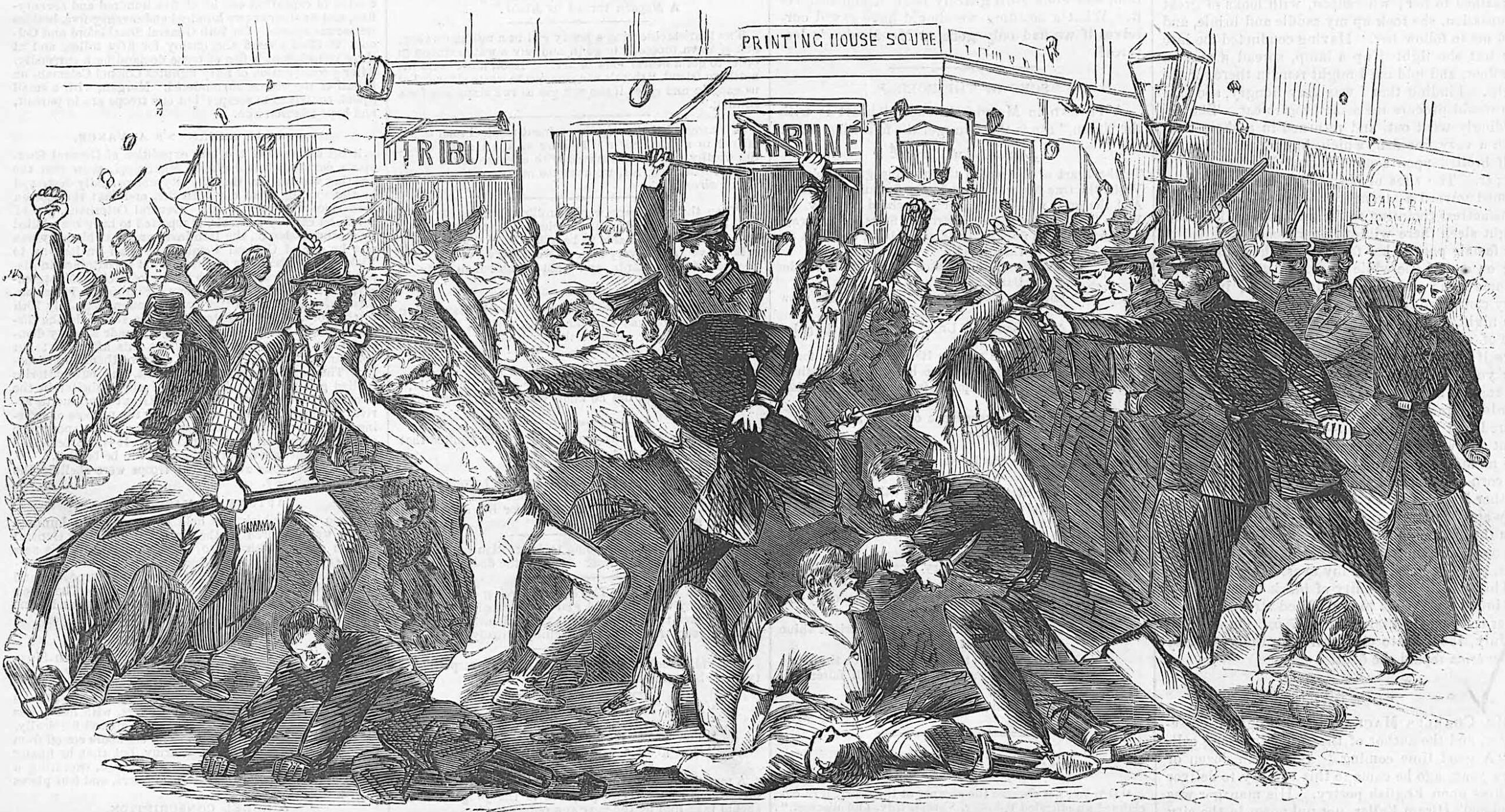

Harper’s Weekly published its own illustration of the struggle between police and rioters outside the Tribune building, which the mob had begun to loot and burn before the officers could fight them off. Noted one officer involved in the struggle: “With a shout from a hundred throats … we struck them like a thunderbolt, cleaving and scattering them in utter rout, ruin, and dismay.”

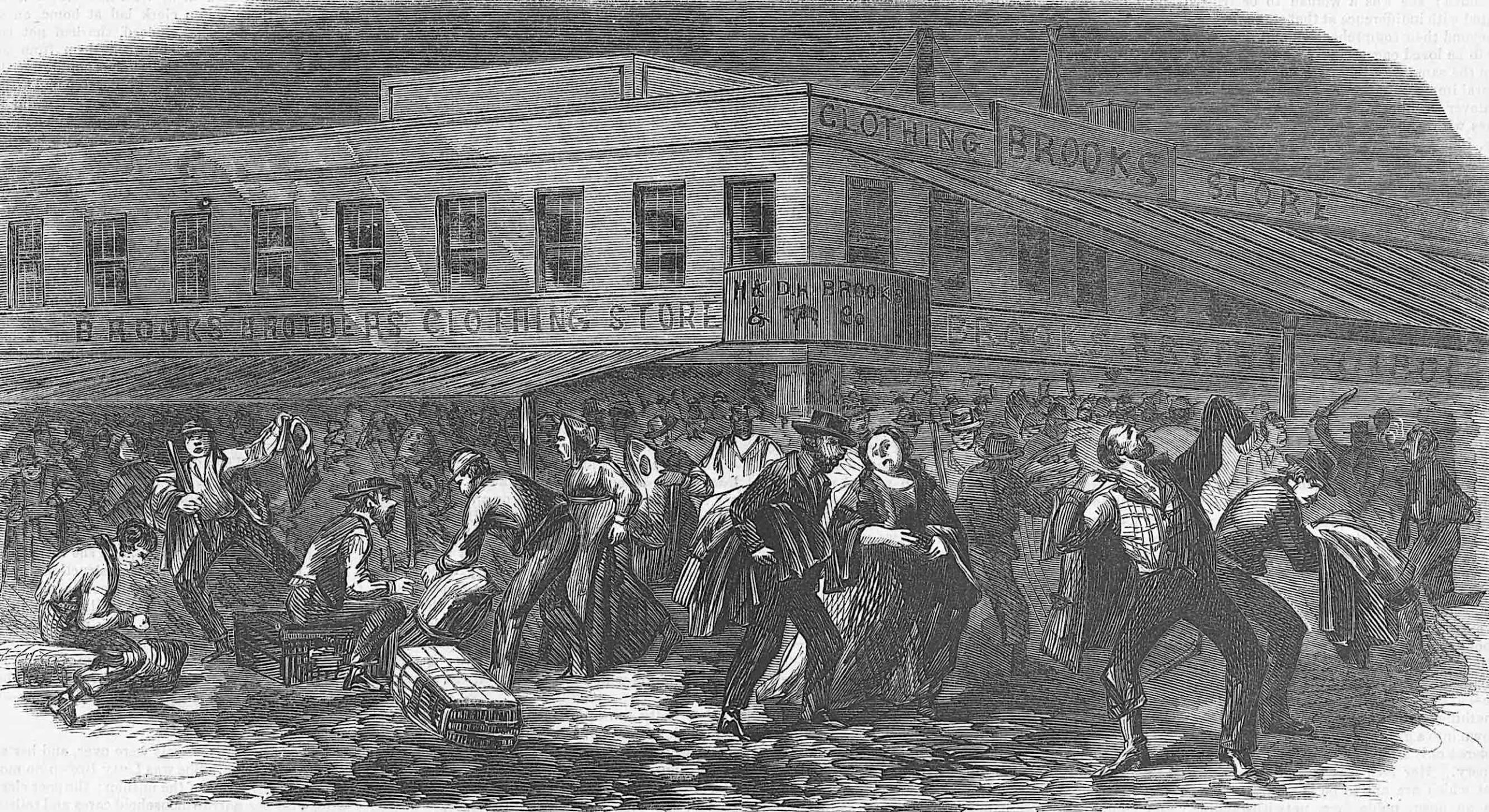

Another target of the rioters (as shown in this Harper’s Weekly sketch) was Brooks Brothers clothing store. The paper’s editors noted, “From the first of the riot clothing appeared to be a great desideratum among the roughs composing the mob…. Here they helped themselves to such articles as they wanted, after which they might be seen dispersing in all directions, laden with their ill-gotten booty.”

The arrival of Union soldiers helped turn the tide against the rioters. In this Harper’s Weekly illustration, troops engage with rioters in the streets. An accompanying article noted that, “when all hope of stopping the proceedings in any other way was gone,” the commanding officer “ordered his men to sweep the streets and then turn their fire on the houses occupied by the rioters. The order was promptly obeyed, and eleven persons, all of whom were ringleaders among the rioters, were shot dead.”

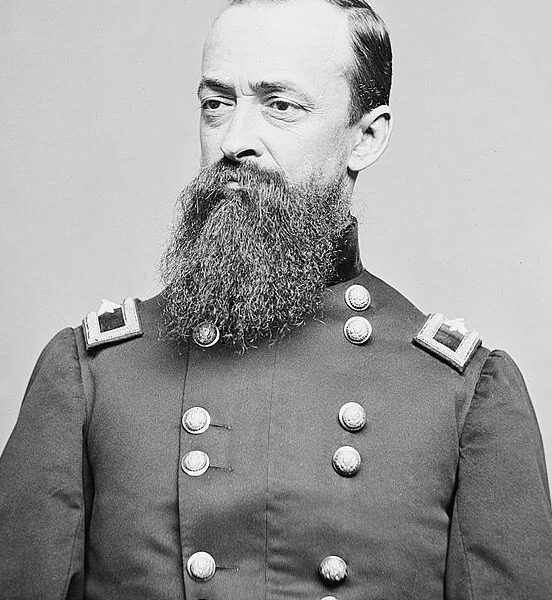

By the time the violence, which spanned four days, ended, hundreds of rioters, soldiers, police officers, and civilians had been wounded—and many others killed. (While no official death toll is available, estimates run from 100–1,200.) Among the military men killed was Colonel Henry O’Brien of the 11th New York Infantry, who was in New York recruiting men for his regiment. O’Brien was attacked by the mob, his body dragged through the city’s streets by a rope, as depicted in this Harper’s Weekly image.

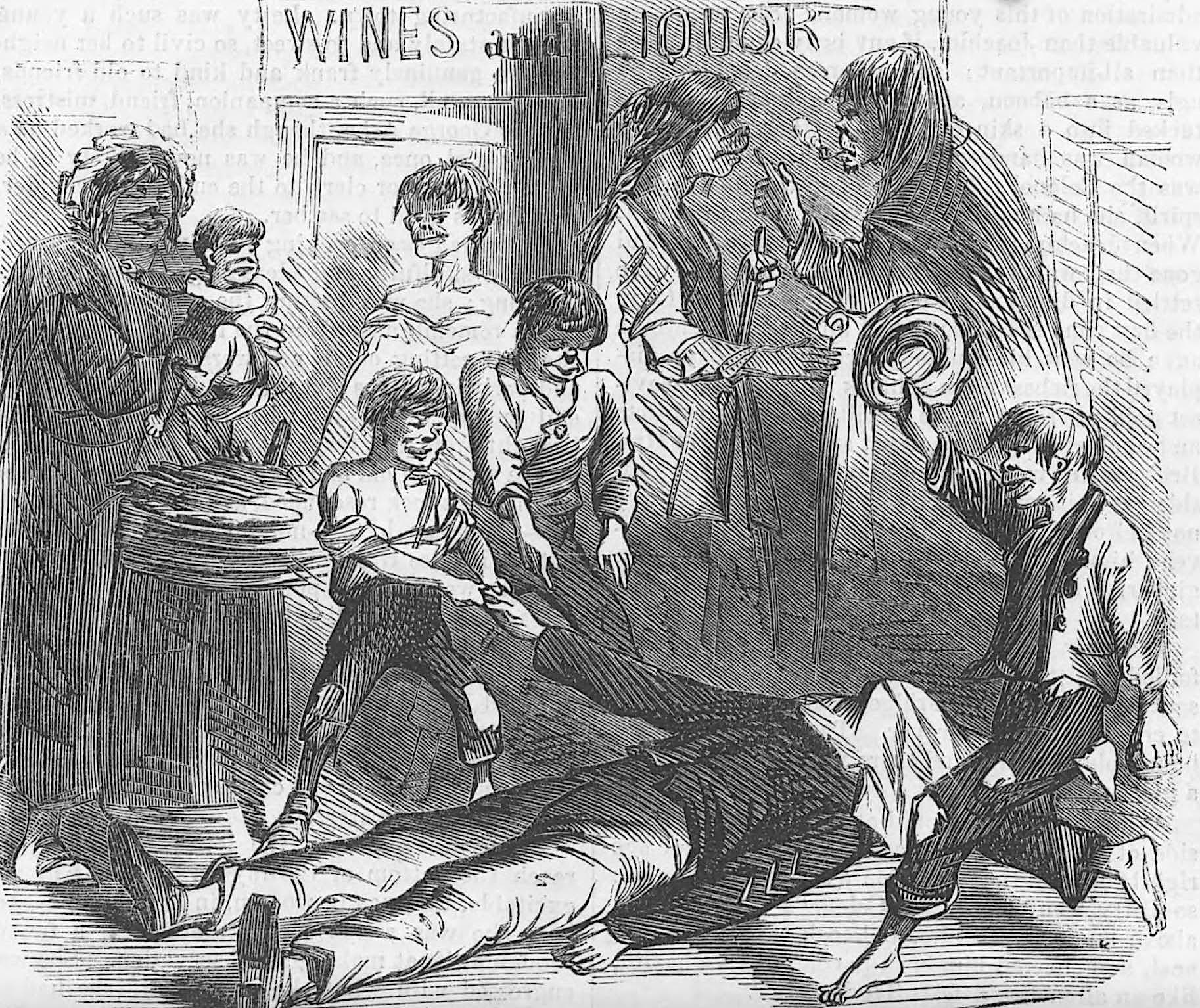

Another Harper’s Weekly illustration shows the body of an army sergeant who, in the words of the man who made this sketch, “was killed by a bullet fired from one of the houses in the vicinity, and then barbarously beaten and mangled by the mob. As he lay there, with a cloth thrown by some decent person over his face, to hide his ghastly wounds, ill-looking women came now and then to look at him, jesting over the unconscious remains, and pointing them out to their infant children with fiendish glee. The little boys amused themselves by lifting up his hands, and then letting them fall to the ground with heavy ‘thud.’ Others performed savage dances around the body, jumping round it, and over it, and even upon it.”

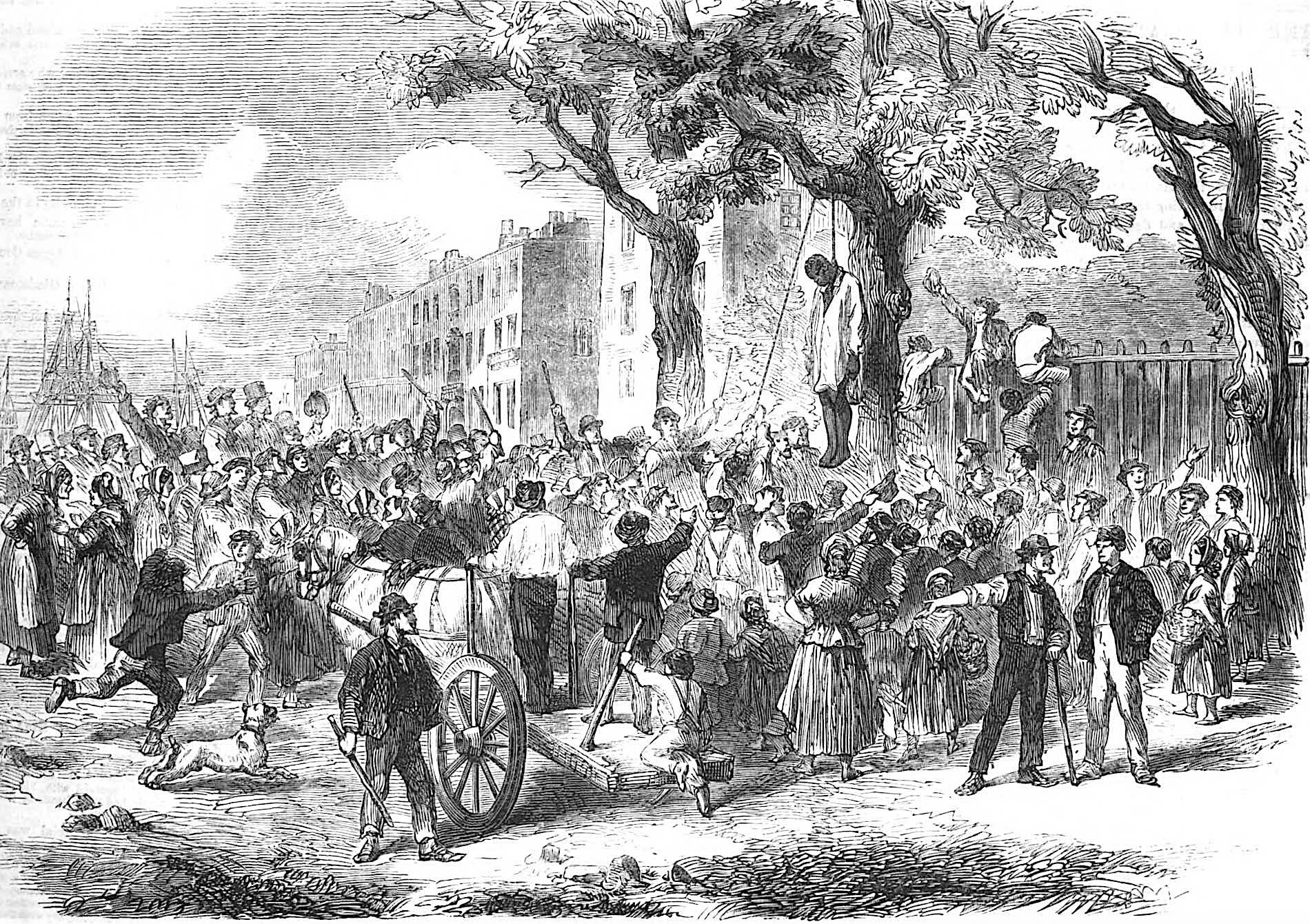

Scenes of the racial violence that occurred were depicted in many newspapers, including The Illustrated London News, which published this scene of a black man lynched by the mob.

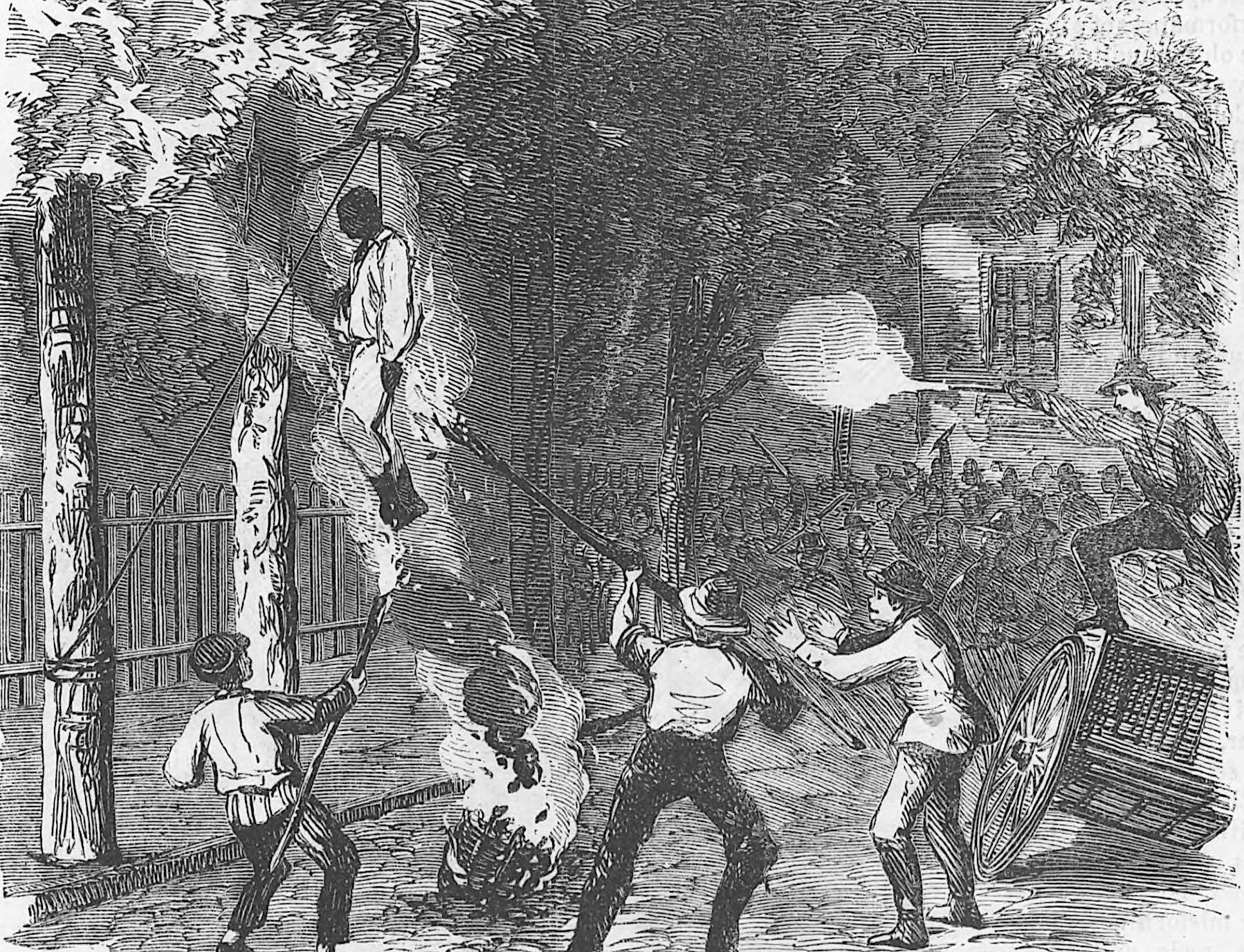

This illustration, captioned “Hanging a Negro in Clarkson Street,” ran in the August 1, 1863, issue of Harper’s Weekly. The editors noted of the scene: “One of the first victims of the insane fury of the rioters was a negro cartman…. A mob of men and boys seized this unfortunate man … and having beaten him until he was in a state of insensibility, dragged him to Clarkson Street, and hung him from a branch of one of the trees that shade the sidewalk by St. John’s Cemetery…. Procuring long sticks, they tied rags and straw to the ends of them, and with these torches they danced round their victim, setting fire to his clothes and burning him almost to a cinder…. This atrocious murder was perpetrated within ten feet of consecrated ground, where the white headstones of the cemetery are seen gleaming through the wooden railing.”

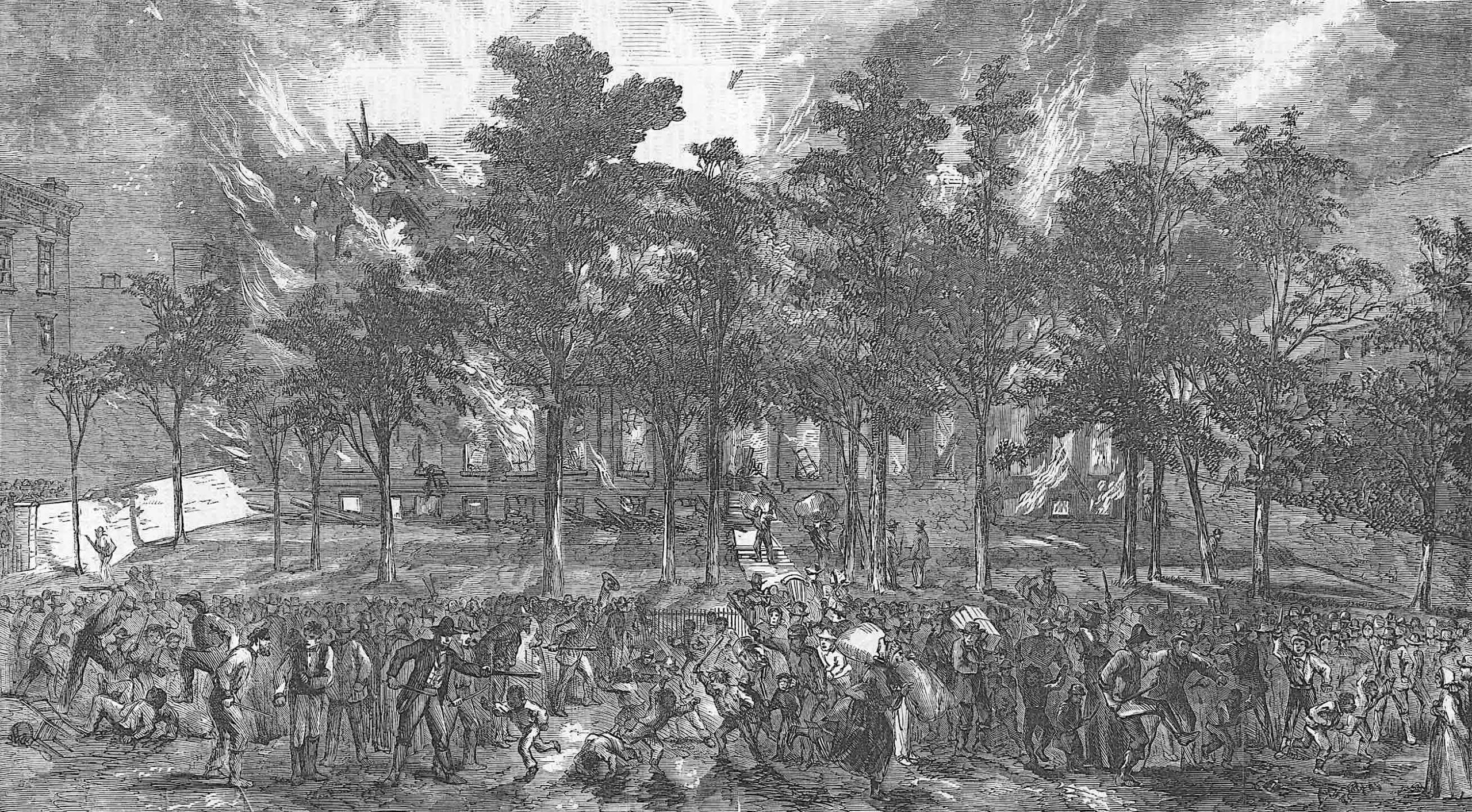

The mob’s burning of the city’s Colored Orphan Asylum (shown here in another Harper’s Weekly illustration) was viewed by the press as a special outrage. In the words of a New York Times reporter, “It hardly seems credible, yet it is nevertheless true, that there were dozens of men, or rather fiends, among the crowd who gathered around the poor children and cried out, ‘Murder the d—d monkeys,’ ‘Wring the necks of the d—d Lincolnites,’ etc. Had it not been for the courageous conduct of … [some citizens], there is little doubt that many, and perhaps all of these helpless children, would have been murdered in cold blood.”

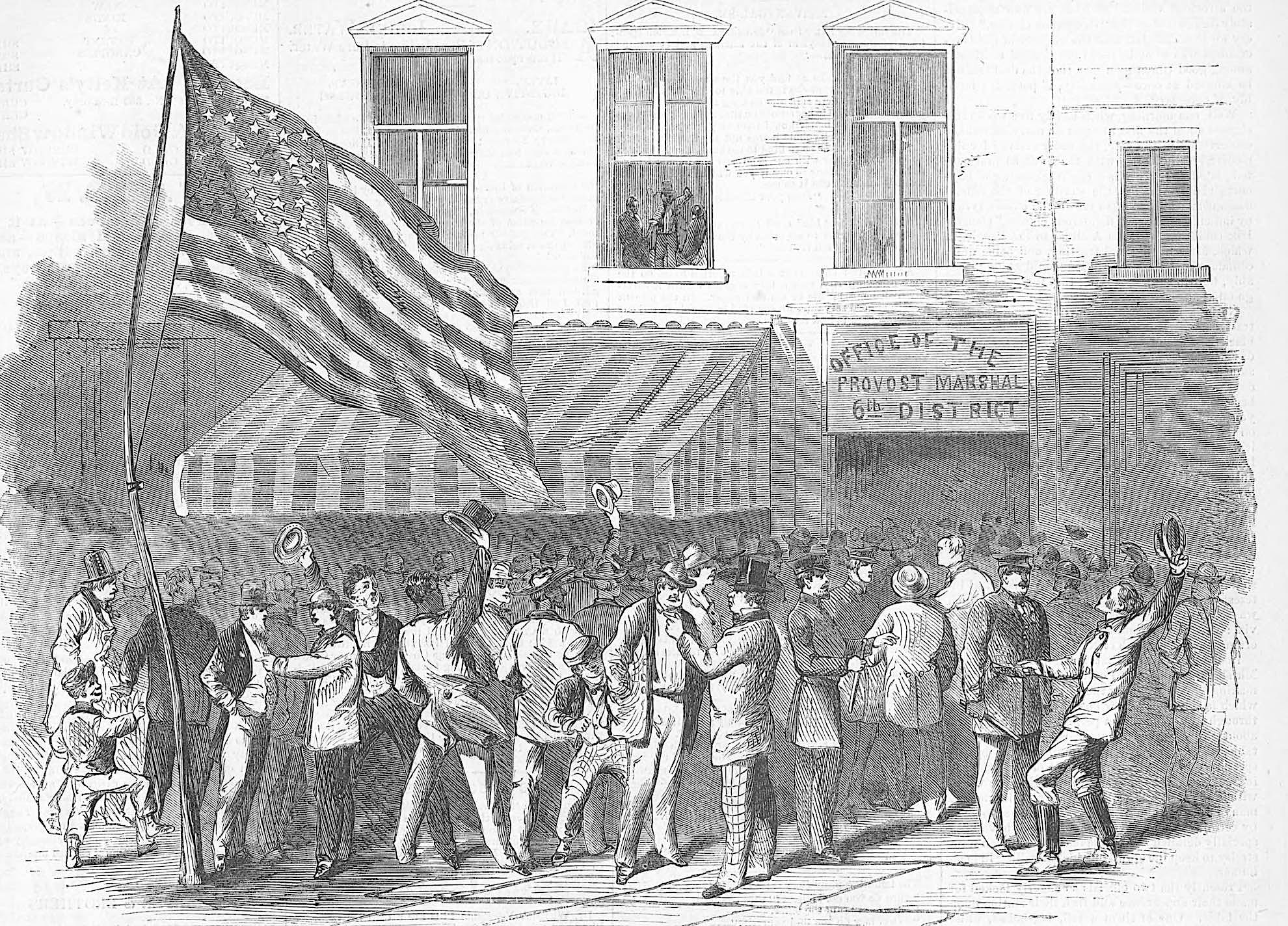

Several weeks after the violence ended and order was restored to the streets of the city, Harper’s Weekly (on September 5) published this illustration of citizens gathered outside the provost marshal’s office celebrating the resumption of the draft. The paper’s editors characterized this as a welcome refutation of some residents’ fears that “the rowdies of New York had once and for all established their superiority over law and order.”

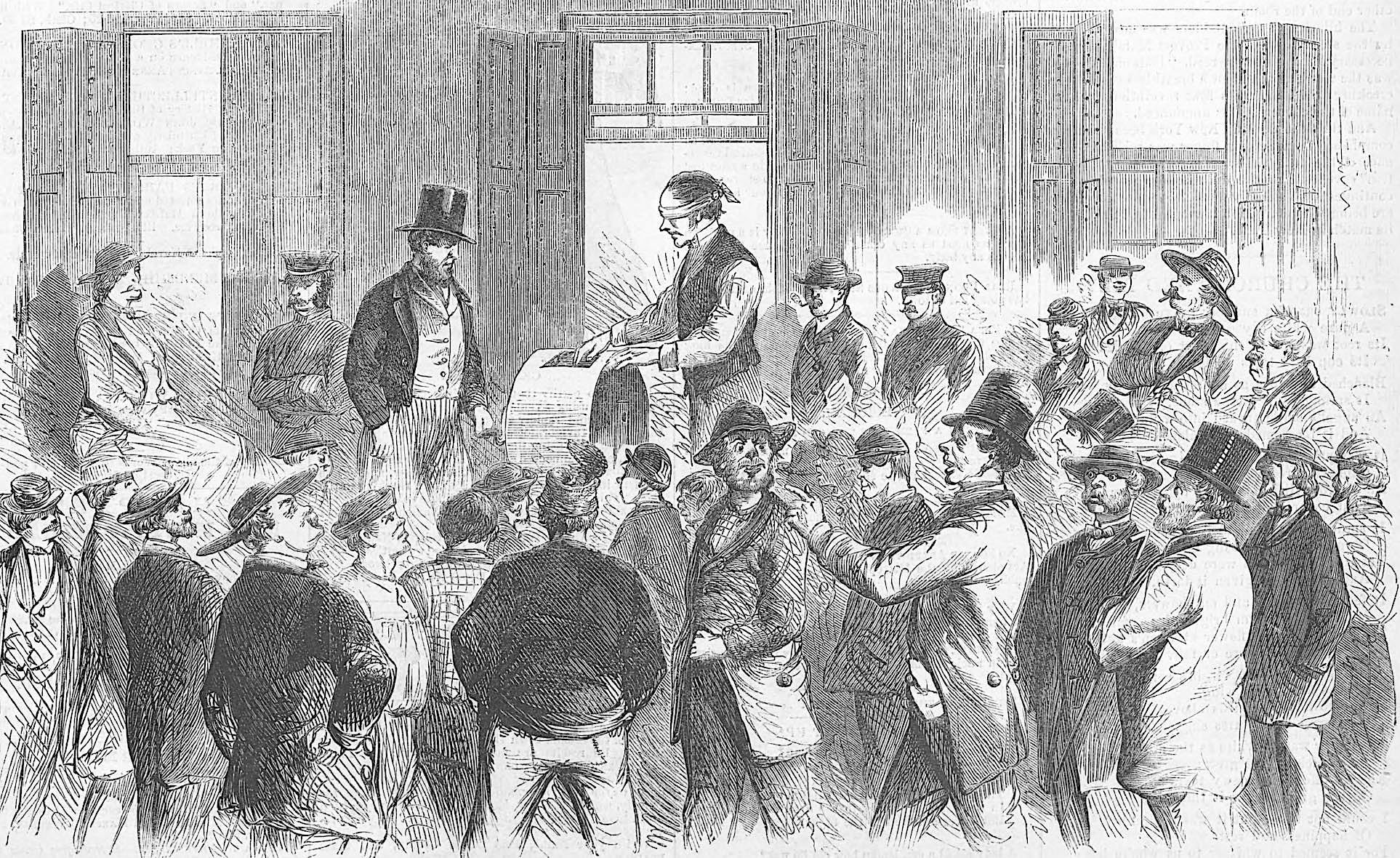

In the same September 5 issue, Harper’s Weekly also ran this illustration of the inside of the provost marshal’s office, where a blindfolded (and therefore impartial) man pulled names from the draft wheel.

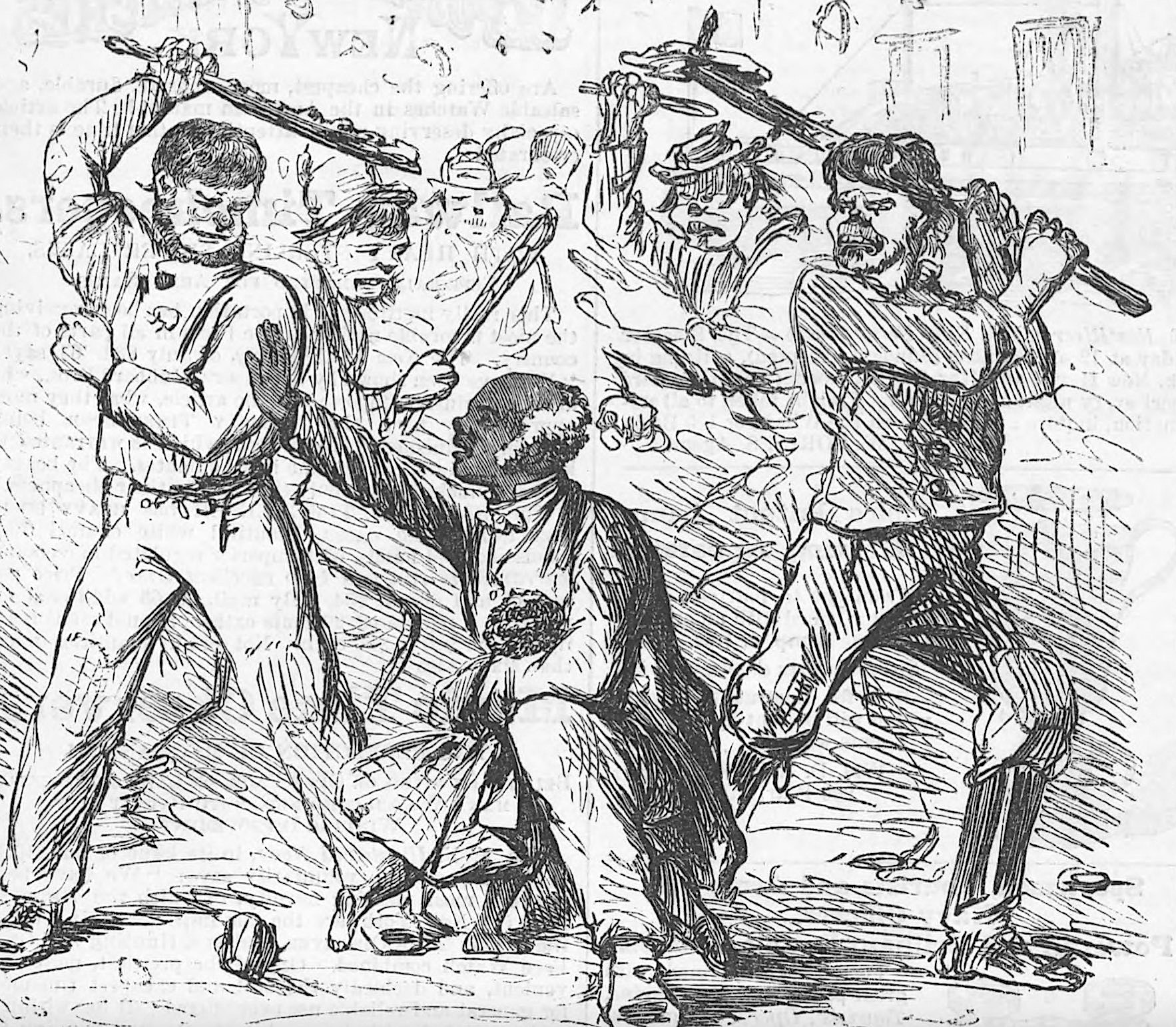

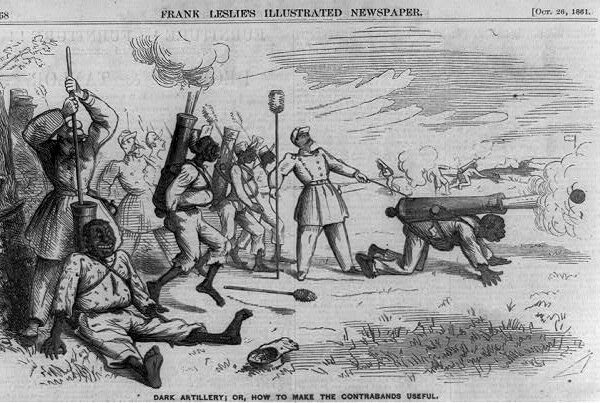

Harper’s Weekly ran several cartoons in the wake of the draft riots that pilloried—or poked fun at—anti-draft New Yorkers. The one shown above, titled “How to Escape the Draft,” shows white New Yorkers on the verge of accosting an African American man and young girl during the violence.

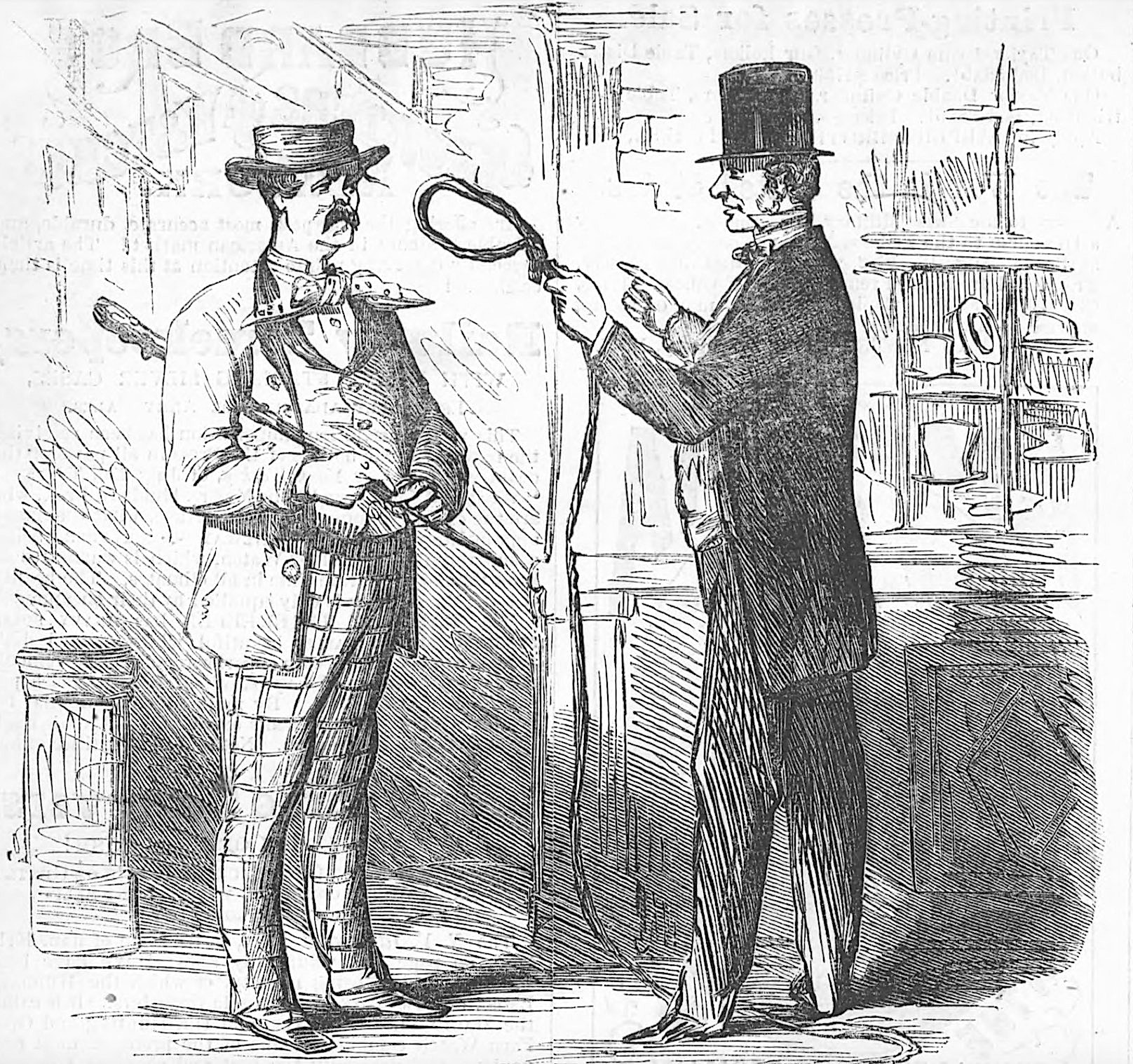

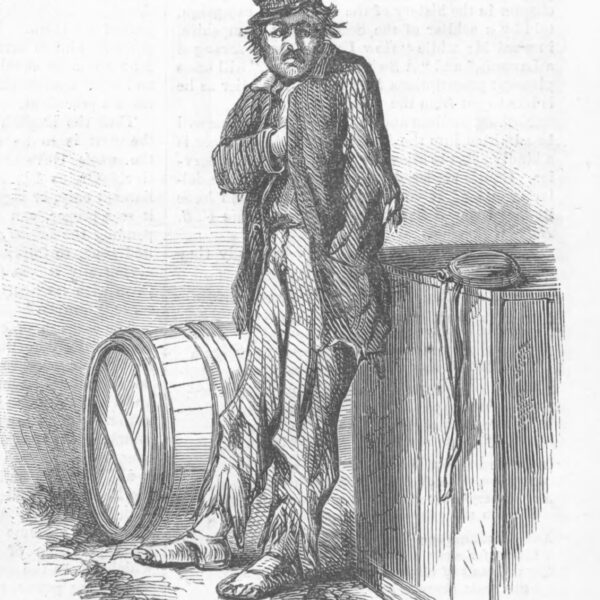

This Harper’s Weekly cartoon, titled “Public Opinion,” depicts two civilians: “One of the ‘People’” (left) and “Mr. Public Opinion.” The former, dressed in new clothes obtained illegally during the riots, says: “No good can come of them Riots we got up, eh? O, brother! Look at me New Clothes, and me ilegant new Neck Tie.” To which the man on the right replies, “Ah! Yes, my friend; but to match the New Clothes, considering how you came by them, allow me to tell you that there is only one kind of New Tie—AND HERE IT IS!”

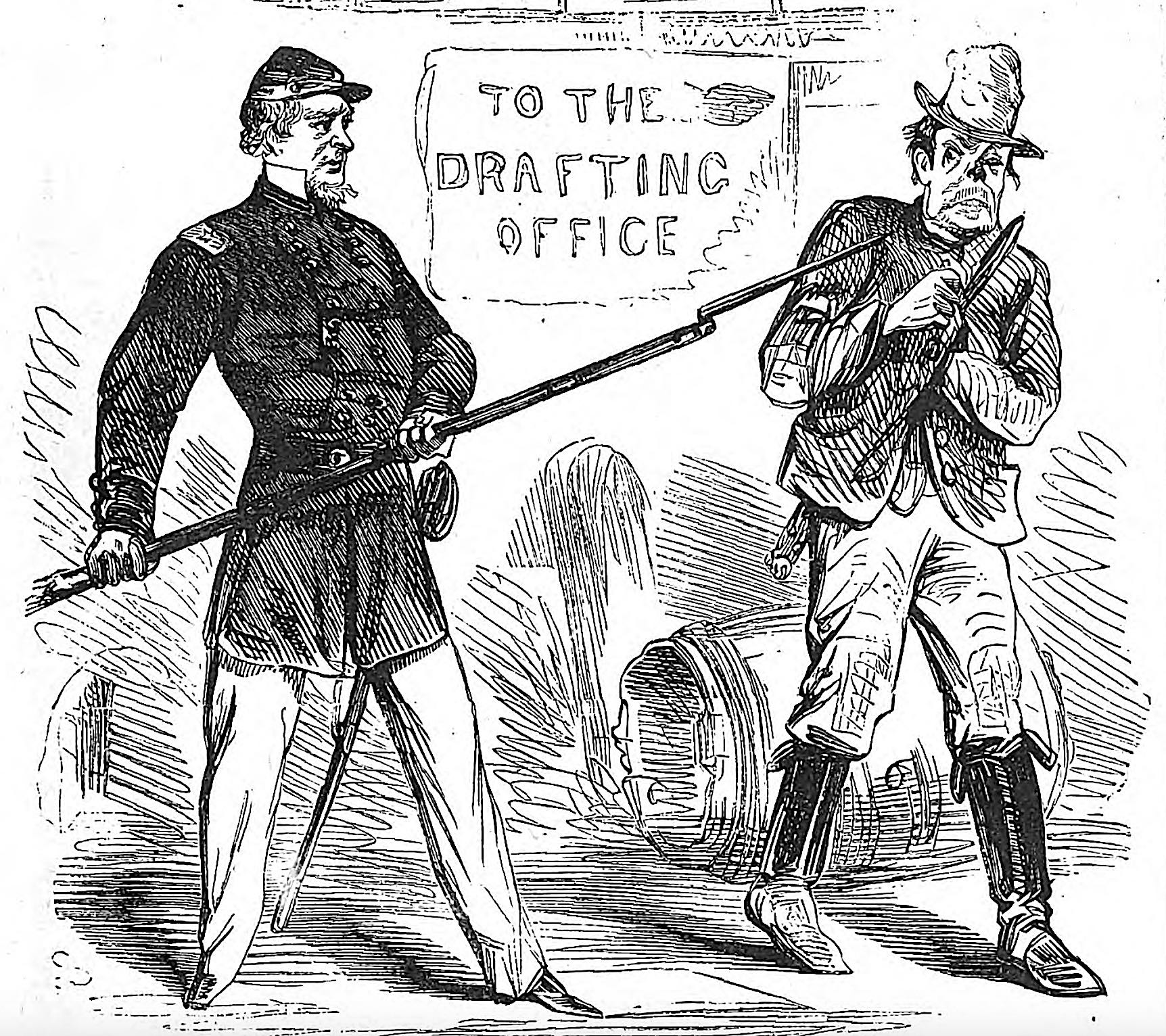

On August 29, Harper’s Weekly published this cartoon titled “Don’t You See the Point?” in which a soldier points his bayoneted rifle at a reluctant draftee before he can resort to violence in an attempt to get out of his obligation to serve.

It appears, based on similar illustrations and cartoons of the time, that many of the rioters are Irish.