If there’s one statistic every Civil War student knows by heart it’s the butcher’s bill: a staggering 750,000 men died between 1861 and 1865. Nor is it a coincidence that we are habitually fascinated, myself included, by the war’s goriest encounters. Men cut down in droves at the Hornet’s Nest, in the Slaughter Pens, assaulting Marye’s Heights, or during Pickett’s Charge come to mind. Ghoulish as it may seem, these episodes—often described casually as “massacres”—are part of the conflict’s magnetic pull.

Historians have debated whether Civil War scholarship has taken a “dark turn,” whether scholars have become enamored of the bloodiest, ugliest, weirdest facets of the conflict. These books would appear to be cases in point. But the concept of a dark turn strikes me as false. After all, what part of a war that killed so many men and unleashed such destruction isn’t dark? What these books invite us to do is dive deeper into what belligerents—who were humans just like us—were capable of doing to each other. Only with that established can we begin to understand the Civil War experience and how it resonates in the present.

That said, there are massacres and there are Massacres. The former typically involved a lopsided outcome: men killed en masse, a unit shattered, or perhaps an attacking army stopped in its tracks. The latter are more sinister. To be sure, they were killing events in their own right, yet ones generally marked by flagrant moral transgressions, scandals of command, heinous abuses of authority, or some combination of those three. Perpetrated by both Federal and Confederate forces, these “capital M” massacres frequently saw civilians, political dissenters, surrendering troops, African Americans, or Native Americans victimized. This admittedly grim column features some of the best books about some of the worst behavior the Civil War and its aftermath have to offer.

Victims: A True Story of the Civil War

By Phillip Shaw Paludan

(University of Tennessee Press, 1981)

Published more than 40 years ago, Phillip Shaw Paludan’s Victims is still the gold standard in historical coverage of a notorious Civil War massacre. Revolving around the isolated community of Shelton Laurel, North Carolina, and an 1863 mass execution of alleged Union sympathizers (including teenagers as young as 13) by Confederate troops, Paludan tells an engrossing story—but also employs the Shelton Laurel Massacre to dismantle a number of misconceptions about the South and the conflict more broadly. For starters, the fact that Confederate forces gunned down southerners explodes the notion of a “Solid South” united behind the Confederate cause. Better still, the cultural variances so expertly parsed by Paludan reveal that while the soldiers and their victims are both considered southern today, they essentially came from different worlds. And, finally, Victims was really the first book to chronicle how women—who were brutally tortured to reveal the whereabouts of their male kin—were on the front lines of guerrilla warfare all along.

Published more than 40 years ago, Phillip Shaw Paludan’s Victims is still the gold standard in historical coverage of a notorious Civil War massacre. Revolving around the isolated community of Shelton Laurel, North Carolina, and an 1863 mass execution of alleged Union sympathizers (including teenagers as young as 13) by Confederate troops, Paludan tells an engrossing story—but also employs the Shelton Laurel Massacre to dismantle a number of misconceptions about the South and the conflict more broadly. For starters, the fact that Confederate forces gunned down southerners explodes the notion of a “Solid South” united behind the Confederate cause. Better still, the cultural variances so expertly parsed by Paludan reveal that while the soldiers and their victims are both considered southern today, they essentially came from different worlds. And, finally, Victims was really the first book to chronicle how women—who were brutally tortured to reveal the whereabouts of their male kin—were on the front lines of guerrilla warfare all along.

River Run Red: The Fort Pillow Massacre in the American Civil War

By Andrew Ward

(Viking, 2005)

In Ken Burns’ 1990 documentary The Civil War, southern novelist-turned-historian Shelby Foote characterized Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest as one of the conflict’s two true geniuses. (The other being Abraham Lincoln.) On one hand, Foote noted that Forrest, as a cavalry tactician, was utter hell on opposing Union commands. On the other hand, Foote overlooked that Forrest orchestrated the subject of Andrew Ward’s River Run Red, an April 1864 massacre of United States Colored Troops at Fort Pillow, Tennessee. When the federal government began enlisting black soldiers, the Confederate government responded by declaring that non-white combatants would not be treated like regular soldiers. Along the banks of the Mississippi, Forrest’s men carried out that policy. Ward’s captivating narrative highlights the perspective of the USCT and the men’s interaction with their white Union comrades—who often weren’t much better behaved toward blacks than their Confederate counterparts. In capturing that dynamic, River Run Red’s take on the Fort Pillow Massacre emphasizes just how universally complicated the issue of black troops was as late as 1864.

In Ken Burns’ 1990 documentary The Civil War, southern novelist-turned-historian Shelby Foote characterized Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest as one of the conflict’s two true geniuses. (The other being Abraham Lincoln.) On one hand, Foote noted that Forrest, as a cavalry tactician, was utter hell on opposing Union commands. On the other hand, Foote overlooked that Forrest orchestrated the subject of Andrew Ward’s River Run Red, an April 1864 massacre of United States Colored Troops at Fort Pillow, Tennessee. When the federal government began enlisting black soldiers, the Confederate government responded by declaring that non-white combatants would not be treated like regular soldiers. Along the banks of the Mississippi, Forrest’s men carried out that policy. Ward’s captivating narrative highlights the perspective of the USCT and the men’s interaction with their white Union comrades—who often weren’t much better behaved toward blacks than their Confederate counterparts. In capturing that dynamic, River Run Red’s take on the Fort Pillow Massacre emphasizes just how universally complicated the issue of black troops was as late as 1864.

The Colfax Massacre: The Untold Story of Black Power, White Terror, and the Death of Reconstruction

By LeeAnna Keith

(Oxford University Press, 2008)

On Easter Sunday, 1873, a heavily armed mob of whites attacked a fortified courthouse in Colfax, Louisiana. Inside were roughly 150 African-American militiamen—Republicans who had recently won control of the local government. Many of them were Civil War combat veterans. And though they were determined to hold their position, they were eventually overwhelmed by superior numbers. The mob slaughtered nearly all of them after surrender. LeeAnna Keith’s The Colfax Massacre not only pieces together the gruesome story of the killings, but also outlines how the massacre influenced the course of Reconstruction. In the years leading up to 1873, President Grant’s administration had passed, and enforced, legislation aimed at stripping anti-black paramilitary groups of power. But the killings in Colfax, coupled with the U.S. Supreme Court’s unwillingness to hold any of the perpetrators accountable, signaled to all the former Confederate states (along with Kentucky and Missouri) that extra-legal violence was still the most effective way to suppress African-American rights—a strategy that Keith notes would underpin the Jim Crow era.

On Easter Sunday, 1873, a heavily armed mob of whites attacked a fortified courthouse in Colfax, Louisiana. Inside were roughly 150 African-American militiamen—Republicans who had recently won control of the local government. Many of them were Civil War combat veterans. And though they were determined to hold their position, they were eventually overwhelmed by superior numbers. The mob slaughtered nearly all of them after surrender. LeeAnna Keith’s The Colfax Massacre not only pieces together the gruesome story of the killings, but also outlines how the massacre influenced the course of Reconstruction. In the years leading up to 1873, President Grant’s administration had passed, and enforced, legislation aimed at stripping anti-black paramilitary groups of power. But the killings in Colfax, coupled with the U.S. Supreme Court’s unwillingness to hold any of the perpetrators accountable, signaled to all the former Confederate states (along with Kentucky and Missouri) that extra-legal violence was still the most effective way to suppress African-American rights—a strategy that Keith notes would underpin the Jim Crow era.

Into the Crater: The Mine Attack at Petersburg

By Earl Hess

(University of South Carolina Press, 2010)

Anyone who has seen the Battle of the Crater scene in the 2003 movie Cold Mountain knows what a vicious fight broke out after Union sappers tunneled beneath and blew up a section of the Confederate trench line during the Siege of Petersburg. Ill-commanded Federals went down into the resulting crater rather than moving around it to consolidate the breakthrough, found themselves unable to climb out, and were then cut down by responding Confederate units. Within the chaos, USCT soldiers were singled out, were refused the ability to surrender, and were executed by Confederates. (Civil War cinephiles have seen a glimpse of this in an extended version of the scene.) Earl Hess’ Into the Crater captures the savagery of the July 1864 battle while also considering different command styles (Ambrose Burnside botching it), command relationships (U.S. Grant loathing Burnside), military strategy and fortifications, and the battle’s ramifications for the wider Petersburg Campaign. In other words, while studies of massacres tend to approach them as anomalous episodes (compared to “normal” or “regular” engagements), Hess uniquely analyzes the butchery in the Battle of the Crater from a traditional military perspective.

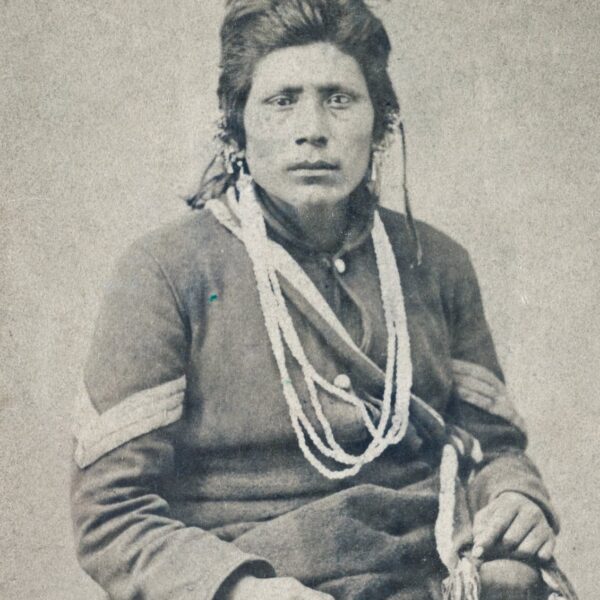

A Misplaced Massacre: Struggling Over the Memory of Sand Creek

By Ari Kelman

(Harvard University Press, 2013)

In November 1864, Colonel John Chivington led his 3rd Colorado Cavalry into battle and claimed more than 100 enemy lives. Unfortunately, as Ari Kelman chronicles in A Misplaced Massacre, the slain were mostly women, children, and elderly members of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes. They had been camped at Sand Creek in the Colorado Territory under a friendly flag when Chivington arrived to exterminate them. At first glance, this would appear to be a Wild West story—a clash between the U.S. cavalry and hostiles. As Kelman so deftly argues to the contrary, the story of Sand Creek belongs to the Civil War and that’s how we ought to remember it. A Misplaced Massacre was on the cutting-edge of the “New Civil War in the West”—a movement that forced us (and still forces us) to consider that the war about slavery was also about determining the face of the postwar nation as it extended all the way to the Pacific. Chivington and myriad others intended that face to be white.

In November 1864, Colonel John Chivington led his 3rd Colorado Cavalry into battle and claimed more than 100 enemy lives. Unfortunately, as Ari Kelman chronicles in A Misplaced Massacre, the slain were mostly women, children, and elderly members of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes. They had been camped at Sand Creek in the Colorado Territory under a friendly flag when Chivington arrived to exterminate them. At first glance, this would appear to be a Wild West story—a clash between the U.S. cavalry and hostiles. As Kelman so deftly argues to the contrary, the story of Sand Creek belongs to the Civil War and that’s how we ought to remember it. A Misplaced Massacre was on the cutting-edge of the “New Civil War in the West”—a movement that forced us (and still forces us) to consider that the war about slavery was also about determining the face of the postwar nation as it extended all the way to the Pacific. Chivington and myriad others intended that face to be white.

Matthew Christopher Hulbert is Elliott Associate Professor of History at Hampden-Sydney College. He is the author or editor of five books and is currently writing a narrative history of the August 1863 Lawrence Massacre.