Library of Congress

Library of CongressAdaline Tyler

I’m pleased to be assuming oversight of the Monitor’s “Civil War Medicine” column previously managed by historian Jonathan S. Jones. Moving forward, installments will draw inspiration from Woman’s Work in the Civil War (1867), a sprawling compendium of female service compiled by L.P. Brockett and Mary C. Vaughan. The book is sentimental in tone, but the biographies in Part II, “Ladies Who Ministered to the Sick and Wounded,” offer contemporary insight into Civil War medical care. Each post will spotlight one woman and explore how her training, labor, judgment, or material conditions shaped medical outcomes and public perception. Rereading these stories through a medical history lens reveals the emergence of wartime systems, ethical dilemmas, and expertise that contributed to the transformation of American medicine and public perception of women’s roles within medical institutions.

Decades before American nursing was institutionalized through professional schools, Mrs. Adaline Blanchard Tyler was practicing medicine with moral rigor and precision. In 1853, a widow in her 40s in Boston, Tyler became a deaconess in the Episcopal Church. She then traveled to Kaiserswerth, Germany, to receive medical training at the same Deaconess Institute that produced Florence Nightingale. Tyler’s international nursing education became immediately useful as the crisis emerged in the United States.

Adaline Tyler’s brief vignette in Woman’s Work in the Civil War reveals how female hospital superintendents helped transform caregiving from a charitable impulse into a form of professional advocacy, using administrative authority, moral clarity, and even media strategy to demand accountability in medical care.

In 1861, Tyler was head of a church-funded infirmary in Baltimore. She was completing her weekly “errands of mercy” to visit local prisons when news reached her of a riot unfolding. On April 19, just days after the fall of Fort Sumter, a clash occurred between pro-Confederate civilians and Union troops traveling through Maryland, and Tyler found herself immersed in the aftermath of an urban battlefield. Moved by reports of wounded Union soldiers, Tyler attempted to enter the Station House to provide aid. She was initially denied access by local authorities but eventually secured permission to transfer the injured to the Deaconesses’ Home. There, she called for a surgeon and directed treating the injured with “the care and kindness of a mother.”1

This episode laid the groundwork for Tyler’s formal appointment as superintendent of Camden Street Hospital in Baltimore. During the war, female hospital superintendents in Union medical facilities oversaw the daily operations of hospitals, managed nurses and supplies, enforced sanitation and discipline, and coordinated patient care. They acted simultaneously as administrators and moral authorities, often advocating for soldiers’ welfare while maintaining order and efficiency in chaotic medical environments as they received patients transferred from battlefields and camps. Their work blended domestic and religious ideals with emerging professional responsibilities, reshaping expectations of women’s roles in wartime medicine.

While at Camden, Tyler’s insistence on impartial treatment for all patients, regardless of their political allegiances, provoked suspicion. She declared that all who entered her hospital would be treated equally, and rumors spread that she harbored Confederate sympathies.2 Though no concrete evidence supported the claim, she was dismissed. (In Baltimore and nearby Washington, heightened wartime suspicion led to the removal of men and women from positions of authority based on the slightest hints of disloyalty.3)

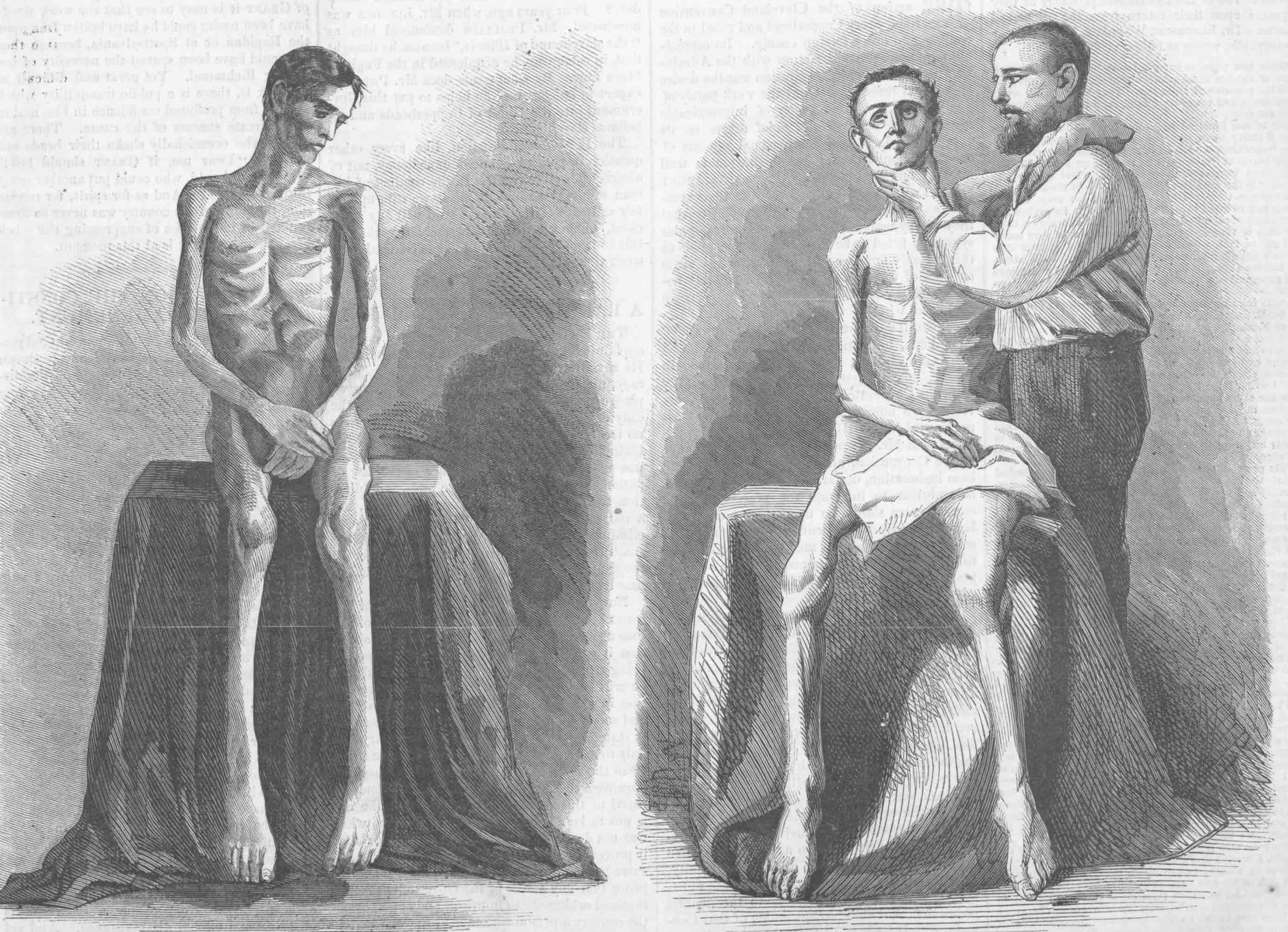

After a year managing a hospital in Chester, Pennsylvania, Tyler was appointed superintendent of the Naval School Hospital in Annapolis, Maryland. There she confronted one of the most harrowing aspects of Civil War medicine: the rehabilitation of paroled Union prisoners returning from notorious Confederate prison camps at Andersonville and Belle Isle. The men arrived emaciated, diseased, and often psychologically broken. In addition to organizing their care and recovery, Tyler documented their conditions through photography, a radical and controversial decision.

She commissioned and encouraged the distribution of images of released Union prisoners of war. Brockett and Vaughan wrote that, “Mrs. Tyler procured a number of photographs of these wretched men, representing them in all their squalor and emaciation.”4 The images had the capacity to serve medical purposes. Such a voluminous collection could document evidence of widespread medical neglect and crimes against humanity, as well as contribute to the Army Medical Department’s mandate to catalog illness, injuries, and treatments.

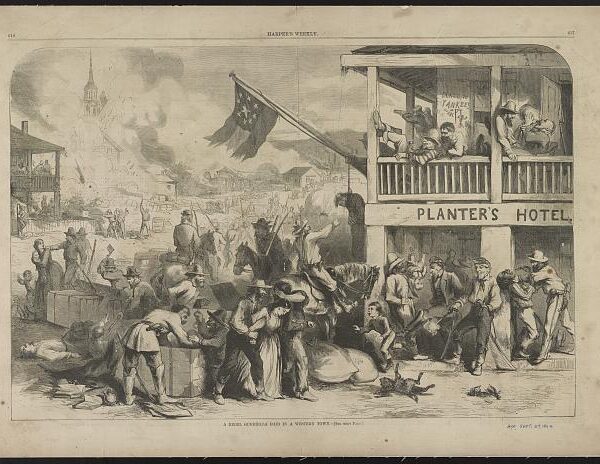

Harper's Weekly

Harper's WeeklyThese illustrations of released Union POWs ran on the June 18, 1864, cover of Harper’s Weekly. Adaline Tyler worked to document the sufferings of such men.

Tyler and other hospital administrators understood the implications of the men’s suffering at this crucial juncture of the war, and they framed it for political effect. Reproductions of selected images from Annapolis were circulated to the public through Harper’s Weekly, whose editors used them to rebut calls for peace negotiations and underscore the moral stakes of the Union cause. As a result, the Annapolis photographs became part of a broader media campaign.5 The decision to commit to the painful documentation of the ravages of imprisonment aligned with her moral imperative to create an “unimpeachable witness of the truth.”6

The hospital’s weekly publication, The Crutch, encouraged patients not to keep silent about their suffering or that of their fellow soldiers: “After you have looked at the picture yourself, send it to your friends, choosing first any rebel sympathizer you may know.… [A]ll boasters of Southern chivalry will be compelled to hide their heads for shame.”7 Publications like The Crutch produced under Tyler’s supervision at Annapolis reflected her concern for patient morale and advocacy. The weekly paper offered patients and staff a shared narrative space as a newspaper and community bulletin. This work underscored Tyler’s insight that healing involved both medicine and patient advocacy.

In May 1864, Tyler resigned from her post at Annapolis due to illness and traveled to Europe, where she convalesced and served as an energetic—if unofficial—ambassador for the Union cause. She visited cities such as Lucerne, Berlin, and London, and found that Europeans of all classes viewed the American war through a pro-southern lens, influenced by Confederate diplomacy and a caricatured view of northern aggression. Tyler took it upon herself to speak about what she had seen. She insisted upon carrying the Annapolis images with her during her travels as the pictures “compelled credence” to those who doubted what she had experienced as a caregiver.8 Her advocacy abroad drew upon her spiritual convictions to speak truthfully and to act with justice.

Adaline Tyler’s story provides perspective on the early professionalization of nursing in the United States. Her advocacy and medical training convey her position as a public intellectual of wartime caregiving: a woman who understood that nursing under the duress and atrocity of a total war was as much about narrative as it was about medicine. Her commitment to impartial treatment, emphasis on documentation, and insistence on orderly institutions all signaled a break from the romanticized image of the self-sacrificing nurse. She was not merely a helpmeet to surgeons; she was a manager, a reformer, and a moral authority.

Though remembered through a sentimental lens in her own time, her story reveals a woman whose work prefigured the structured, ethical, and communicative demands of modern healthcare. She imposed standards where there were none, demanded equal care in the face of prejudice, and wielded media as a tool of moral persuasion.

Megan VanGorder is an assistant professor of history at Illinois State University. Her forthcoming book, A Mother’s Work: Mary Bickerdyke, Civil War-Era Nurse, will be published in Spring 2026 by UNC Press.

Notes

1. L.P. Brockett and Mary C. Vaughan, Women’s Work in the Civil War: A Record of Heroism, Patriotism and Patience. (Philadelphia, Pa: Zeigler, McCurdy & Co., 1867), 244.

2. Ronald S. Coddington, “Adaline Blanchard Tyler: First Nurse,” Library of Congress Research Guides, Civil War Men and Women: Glimpses of Their Lives Through Photography.

3. Quincealea Ann Brunk, “Forgotten by Time: An Historical Analysis of the Unsung lady Nurses of the Civil War,” University of Texas at Austin dissertation (1992), 122-124.

4. Brockett and Vaughan, Woman’s Work in the Civil War, 247.

5. Anne Strachan Cross, “‘The Pictures Which We Publish To-Day Are Fearful to Look Upon’: The Circulation of Images of Atrocity During the American Civil War,” History of Photography, 45:1, 33.

6. Brockett and Vaughan, Women’s Work in the War, 247.

7. The Crutch, May 14, 1864.

8. Brockett and Vaughan, 247.

Related topics: medical care, women