A generation ago, Jay Winik crafted the widely read April 1865: The Month that Saved America, which traced in close detail the history of those fateful spring weeks. He included fifty pages of endnotes, thereby enabling his readers to discern the book’s use of primary and secondary sources. Winik’s sparse new effort, focused on the equally fateful five-month interval between the 1860 presidential election and the outbreak of war, offers no notes or bibliography. Apparently unwilling to engage with those who already have written about these matters, Winik pontificates, complete with seemingly learned allusions to Roman history, the French Revolution, and the British conquest of South Africa. The book comes across as a pronouncement, ex cathedra, rather than a persuasive narrative.

Winik dashes through the prewar years—Charles Sumner, Preston Brooks, Dred Scott, the Lincoln-Douglas debates, and John Brown (the “Mad Prophet”)—to warn that a “volcano was about to erupt” (22). Hindsight is always 20/20, but historian Edward Ayers provides indispensable insights about the overwhelming majority of Americans who believed the Union rested on firm foundations and saw no grave crisis impending. And David Potter’s posthumous masterpiece will remain essential for those who want to know how the pieces of this puzzle fit together.

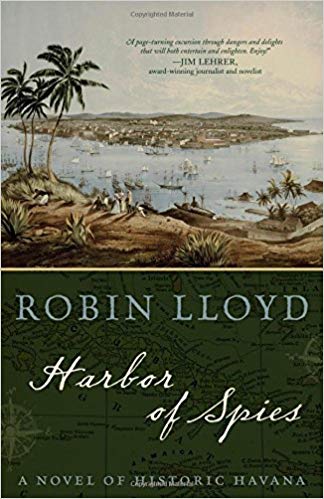

With Lincoln elected in November 1860 and the Deep South bitterly estranged, might a Union-saving compromise still have been possible? Enter John J. Crittenden, “one of history’s unsung figures” (119). Winik champions the Kentucky patriarch as personifying the “lost peace” featured in this book’s subtitle. Without delving deeply into the squalid particulars of Crittenden’s proposal—protecting slavery in southern territories, not just tolerating it, including any territories “hereafter acquired” (think Cuba and the Caribbean), all to be embalmed forever in the Constitution—Winik boosts a might-have-been that has found few friends among modern scholars. The plan was unacceptable to Republicans, wrote the late Don Fehrenbacher, because it was “no compromise at all, but a total surrender”—a form of penance for having won the 1860 election.

Winik, however, must also genuflect before the near-universal modern consensus to celebrate Lincoln for bringing about emancipation and preserving the Union. He consequently finds it awkward to recount the president-elect’s blunt refusal to risk the Republican Party’s rupture by embracing Crittenden. Lincoln, Winik reluctantly writes, “egregiously misjudge[d]” the situation in the South when he dismissed secession “as a sort of political game of bluff” (136, 181). By stating that Lincoln misjudged, Winik introduces another dilemma. New York Senator William H. Seward, Lincoln’s Republican rival, promptly recognized the danger posed by secession and urged a more conciliatory approach to the South, though he never went so far as to swallow Crittenden’s high-octane bourbon. Did Seward’s comparatively dovish approach to the crisis, in Winik’s judgment, elevate the New Yorker? Decidedly not. The Seward depicted here is the familiar meddlesome and deceitful know-it-all, long a punching bag for Lincoln hagiographers. Winik displays no familiarity with historian Russell McClintock’s subtle and nuanced account of the interplay between Lincoln, Seward, and Stephen A. Douglas as the dreadful impasse unfolded.

Much of this book could have been written a century ago. It shares with the so-called revisionist historians of the post-World War One era the idea that a needless North-South war could and should have been averted. Winik clings to the hoary tradition that white Southerners such as Crittenden or Robert E. Lee or even Jefferson Davis found slavery repellent. Even though modern scholars have shown that Southern political discourse forbade any challenge to slavery, even in the distant future, Winik’s spin on the situation leads him to presuppose that leading Southerners might have accepted a sensible Union-saving agreement, had astute Republicans reached out to them.

One lone modern scholar, William Cooper, in an elegantly contrarian and closely-argued volume, We Have the War Upon Us, likewise judged the Crittenden Compromise wise and farsighted, the best way to have preserved the Union without war. But Cooper, unlike Winik, grasps the logic of his stance and consequently depicts Lincoln as a bumbling amateur who was in over his head. Cooper recognizes instead the importance of Seward’s outreach to Upper South Unionists such as John A. Gilmer and George W. Summers.

Too often Winik obscures information that his readers deserve to know. For example, a group of moderate Republicans and Southern Unionists hatched the so-called Border State Plan in January 1861 to remove “protection” and “hereafter acquired”—the two poison pills in the Crittenden Compromise. From that point forward, Crittenden himself promoted the revised version. But Lincoln quashed the Border State Plan and a comparable scheme put forward by the so-called Washington Peace Conference. He would not countenance any concession that might permit slavery to expand. As a last-minute olive branch, Lincoln did accept a constitutional amendment, drafted by Seward and consistent with Republican Party orthodoxy, to prevent any interference with slavery in the states where it already existed.

Winik never displays much curiosity about a key element of his story: how the Deep South’s leading men instigated the secession panic. They insinuated that Republicans would trample the Constitution and enlist John Brown-type marauders to menace the South’s white women and children. They downplayed the danger of war and asserted that Confederate independence would assure the long-term safety of the slave system. Never in American history did political leaders behave so irresponsibly or miscalculate so disastrously.

Daniel W. Crofts, Professor Emeritus of History at The College of New Jersey, has long studied the North-South sectional crisis that led to the Civil War. His 2016 book, Lincoln and the Politics of Slavery: The Other Thirteenth Amendment and the Struggle to Save the Union (University of North Carolina Press), was awarded the University of Virginia’s Bobbie and John Nau Book Prize in American Civil War Era History.

I very much agree with Professor Crofts. My 2025 biography of George Boutwell supports other histories that maintain that the Virginia peace convention, what Winik calls the Washington peace conference, had no chance of avoiding war. Virginia (John Tyler and James Seddon) was seeking assurances from Lincoln that, not even having assumed the presidency, he was not able to give, and wouldn’t have even if constitutionally able. One of those assurances was expansion of slavery, either into the western territories or into the Caribbean. As Seddon said to Boutwell at the conference, “either slavery expands, or the South dies.” For his part, Boutwell one of the leading northern delegates, replied “there can be no peaceful separation. Either you will march your armies of the Great Lakes, or we will march ours to the Gulf of Mexico.” Mr. Winik tries to make the case that a compromise could’ve been reached, which the facts don’t justify. And, as Crofts and others have noted, Winik has no sources or footnotes to justify his assertions. See my Boutwell: Radical Republican and Champion of Democracy (WW Norton, 2025), pp. 79-81.