Historian Court Carney discusses why Nathan Bedford Forrest was not held accountable for the massacre of black soldiers at the Battle of Fort Pillow.

Transcript

Terry Johnston: Court, thanks for joining us. Today’s question, which was submitted to us anonymously from a listener in Maryland, is, “Why wasn’t Nathan Bedford Forrest charged with war crimes for the massacre at Fort Pillow?” Now, before you even get to that answer, let’s have you set the stage for listeners. First, then, who was Nathan Bedford Forrest?

Court Carney: So, Nathan Bedford Forrest was a Confederate general who comes out of the west Tennessee world of slavery and politics. In his early life, he’s very much connected to northern Mississippi. And then he ends up moving to Memphis. And in Memphis, he then has a fairly large and substantial business in terms of the slave trade. And most of his life in his twenties and thirties was sort of built around slavery. And then local politics. He was elected an alderman in Memphis. And he cuts this really fantastical figure even before the Civil War. And fantastical in all of its dimensions because he is a fairly frightening person and he is connected to violence and the code of honor and the entwined code of violence. And that frontier southern mentality is a big part of who he is.

But he lives an entire life before the Civil War. When the Civil War starts and he joins immediately he’s 40. So he has an entire life before that that we could very easily see through the lens of the slave trade and then all the component parts to that. So before you even get to the Civil War, he has this very—I would say frightening, but he is frightening in many ways—but he certainly has a demanding presence, a commanding presence, in the Memphis political realm, social realm.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressNathan Bedford Forrest

Terry Johnston: Well, so the Civil War starts and he gets in. Like you said, he’s 40. He enlists in the army as a private, didn’t he? And he rises through the ranks rather quickly. So by the time of Fort Pillow, he’s a major general and had earned that “wizard of the saddle” reputation as a cavalry leader, right?

Court Carney: Right. He does join as a private. He moves up pretty quickly. The one thing to keep in mind with Forrest is that—Charles Royster, who wrote the very wonderful Destructive War, had the best quote of Forrest, and I still use it to this day. His summation of Forrest was he was a minor player in some major battles, and he was a major player in some minor battles. And I think if we want to summarize someone’s years in the Civil War, that’s pretty close to it. He is a horseman. He is connected to the cavalry. And most of his work in the Civil War will be attached to larger units.

Early on, his big battle is Shiloh. And he will be running interference after the battle to cover the Confederate retreat. Then he’ll be involved in a lot of smaller skirmishes throughout the entire first part of the war. So he’s bouncing back and forth between supporting large troops and then also connecting his smaller groups. We can go deep with some of this, though, because what Forrest is doing is very much connected to his prewar life. One thing that I long argue and I think is important to keep in mind is that, involving the slave trade, he knew all of Tennessee, Mississippi, Kentucky. He knew that area, not just because he lived there, but he knew that area. He knew the contacts. He knew the resources. And one of the things that gave him a lot of power early on with his troops is that he could get his men supplies and horses. And that’s very much connected to the world of slavery for him. So he is this, not anomaly by any stretch of the imagination, but he is this interesting figure because he is famously untrained. He is not military. He is learning and figuring it out on the go. And he’s a pretty good leader. You know, from a leadership perspective, he gets the qualities of what it takes to get people to do what you want them to do. And he has all of that really early on.

The other thing, and we can talk about this later, that I think is important about Forrest is that he’s also very media savvy. His aides-de-camp are Atlanta and Memphis newspaper guys. He has a lot of connection to the media. He’s aware of the media. He’s using the media to his advantage. When we get to Fort Pillow and after Fort Pillow and certainly after the war, he’s very conscious of how he is presented, and he uses that to his advantage.

He likes the idea that, later on, he’s known as “the butcher.” And he relishes that. He really plays into that. So there’s kind of a modernist strain with Forrest where he’s very media savvy and he’s very engaged. In terms of the military, he’s sort of functionally, we would call it, under-literate. But he is very, very, very connected to how his persona is built.

Terry Johnston: Well, let’s definitely come back to that. But first, for people unfamiliar, can you talk some about what Fort Pillow itself was? When was it constructed? Where was it located?

Court Carney: Sure. Fort Pillow is on the Mississippi River just north of Memphis. It was built early in the war as a Confederate fort. The Confederates were using this to protect the river—their holdings in the river and also north of Memphis. It’s taken over by the Union in 1862, and it’s a Union-controlled area for most of the war.

Terry Johnston: Well, and the fort itself, we should say, it’s not a classic fort in the Sumter model of this big masonry structure, right? It’s more like a series of trenches and outbuildings, isn’t it?

Court Carney: This is not a giant stone castle in the hinterland. No, it’s basically a series of ditches. And it’s on a bluff, so it has, like, a natural protective area, especially if you’re thinking about it as guarding the Mississippi. It is not set up in any real way as a real stronghold.

So, the garrisons that are in there are in “a fort,” but it’s not nearly the protective space that the word fort might provide. And if you go there today, they’ve kind of rebuilt part of it, and it gives you a sense of what it looked like—in the sense that you can’t really make sense of it, which is a nicely ironic point I suppose.

Terry Johnston: And it is, like you say, on a bluff overlooking the Mississippi River. And there was, wasn’t there, some kind of Union gunboat presence, now that that part of the river was controlled by Union forces?

Court Carney: Right. Because you have all of the real river action of 1862, when you have New Madrid and these other gunboat battles where the Union is able to take over. And so, yeah, you have gunboat action. You have some military action, very little military action. I mean, the groups that are there, you have an Indiana regiment there for a long time. And they’re drilling and that kind of thing, but they have their own sort of existence. And there are tons of stories where they get involved—the Union soldiers—in all sorts of illicit trade, contraband. There are accusations of dealing with slavery. There’s all sorts of stuff that’s going on underneath all of this. So, it’s not a real overrun military area, but you do have the gunboats on the river and you do have the regiments filtering in and out throughout the middle part of the war.

Terry Johnston: Well, and speaking of the actual garrison, it wasn’t just white soldiers at the time of the Battle of Fort Pillow. There’s some sizable element of black troops.

Court Carney: Right. So, Fort Pillow, again, is a small little spot. Throughout 1862 and 1863, you have a bunch of all white Union soldiers there. But by early 1864, those groups have moved out. And what you have there is a white cavalry unit. And then you have several companies of the 6th U.S. Artillery, and that is a black unit led by a white officer by the name of [Lionel] Booth.

Their presence by 1864 is what changes the local story because you have black soldiers in the fort. Many of these soldiers are actually from the area. And so then you have all of these tensions that had already existed when you just had white soldiers there, but then the presence of the black soldiers creates this whole heightened sense by the spring of 1864. And that’s what eventually pulls Forrest into the story. He hadn’t really been a part of that early on. That’s not to suggest there weren’t tensions and annoyances by white Confederate Tennesseans before this. But then when you put in the 6th U.S. Artillery, that’s what brings everything to a head.

Terry Johnston: Well, so now let’s get to the actual battle itself. First and foremost, why does Forrest focus his attention on Fort Pillow in April 1864?

Court Carney: So Forrest in 1864—for people who have a very detailed knowledge of the Civil War, this makes sense, but if you don’t have a very detailed knowledge of the Civil War—Forrest in 1864, not to be flippant, but he’s on his “side-quest” part of his story. He has probably between 1,500 and 3,000 soldiers. He’s dividing up his soldiers continuously. That’s his M.O. during this period. He’s not connected really to any big battles right now. His last major battle was Paducah. And so he is going off on these raids. And he does this throughout his career in the Civil War, but this is a particular time when he is dividing his forces and going through Kentucky and Tennessee. There’s times when he is going through Mississippi and Alabama. And he’s getting involved in these small skirmishes. I mean, they are still battles and people are dying, but these are some smaller, 1,500, 2,000 forces versus maybe a similar number, a little bit smaller, a little bit larger. So throughout the spring of 1864, that’s kind of what Forrest is doing. He’s not involved in major, major battles.

So, he is running through this area and he begins to pick up more and more information about Fort Pillow because of the black troops stationed there. So then he pivots. And he is going through these different skirmishes and he decides to go take care of Fort Pillow. I think his language at one point is, “I’m going to take care of that situation” or something like that. So he then moves toward Fort Pillow.

Now again, remember Forrest is very much a part of the Memphis story. He is very much part of the northern Mississippi story. So this is all stuff he knows. This is an area he knows. And so he’s basically being called in a little bit by the local people. And also he’s in this mode where he’s doing this a lot. And so then when he ends up getting to Fort Pillow in April, this is just one more step of it.

What I would like to emphasize is that he is not saying, “This is my time to go to battle here.” Fort Pillow is not like that for him. Fort Pillow is one of, maybe, half dozen battles he’s been doing in a very similar vein. And you have a very similar story where he is facing Union soldiers and he’s using the fear of no quarter, where he’s announcing to the Union garrisons or the Union soldiers he is meeting that if they don’t surrender, he is going to kill them all.

And he’s using that as a bluff or as a “bluff-adjacent,” you know, throughout this period. So when he does that at Fort Pillow, not to get ahead of the story, he’s been doing this elsewhere too. So Fort Pillow, from the Forrest perspective only, is not that unusual or that unique when he shows up in April.

Terry Johnston: So, on April 12, then, Confederates surround the fort. They greatly outnumber—I think it was an approximately 600-man Union garrison at the time—maybe they outnumbered them four to one. What happens next?

Court Carney: The interesting thing is that Forrest, his second in command is there early and has set up surrounding the fort. So the Confederates have a line of sharpshooters in the trees. They’re able to pick off Union soldiers in the fort pretty easily. They’re able to, by early in the morning on April 12, take the—I want to say high ground, which is both literal and also figurative—but they’re able to take control of the surrounding areas. Forrest shows up to Fort Pillow probably mid-morning. He gets there around 10 or so, which is an important point because the battle’s already set. Not the battle itself, but the battlefield is set before he gets there. And by that point, they then begin to creep forward and take over the different outbuildings and parts of the fort that were scattered into the woods basically. So that’s all happening in those first couple of hours.

You have the garrison beginning to burn some of these buildings. That’s going to be part of this issue. They’re retreating back into where they can find protection. And then you have Confederate sharpshooters knocking off people throughout. Importantly, Booth, who is the commander of the black units, is killed very early on, but the Union hides that. So Forrest doesn’t know that the commanding officer is dead. They sign notes back and forth. You have another Union officer pretending to be Booth. You have a guy named [William F.] Bradford who is basically signing off his Booth. So there’s all these kind of peculiarities going on there.

But basically, you have this back and forth, burning of buildings, creeping forward, threats of storming the building, up until about sometime in the mid-afternoon. And that’s when things begin to shift. You basically have Forrest saying, “Look, we’re storming the fort. We’re coming over.”

Terry Johnston: And he actually sends—this is a flag of truce, isn’t it?—he sends official word, like, “You’ve got to surrender or else.”

Court Carney: Right. So, to set the scene, by the mid-afternoon you have disarray in the fort itself. You have buildings on fire, which they had lit themselves to prevent Confederates from taking them over. You have Confederates amassing troops around the trees in a semicircle around the fort, because the other part of the fort’s against the river. And then you have this back and forth with letters. Well not letters, but they’re communicating back and forth during that period.

Terry Johnston: And so Forrest is saying what, basically?

Court Carney: Surrender or I’m going to assault the fort. And if you don’t surrender, then I’m not protecting anybody there. There will be no prisoners. So, the thing he’d been doing throughout the spring of 1864, he does again here. “I cannot be responsible for the fate of your command,” is what he tells the Union. This is, again, under a flag of truce, as you mentioned. And this is where things get tricky too, because there are charges to this day that the flag of truce was not really being abided by either side. Under a flag of truce, Forrest would not be able to move soldiers around. And he was doing that too. So there’s a lot of murkiness here of what was going on. But by the mid-afternoon it was clear that Forrest was saying, “Look, I’m going to take this fort over. If you don’t surrender, I’m not going to be bound by any prisoners of war,” basically. No one’s escaping this, in other words.

Terry Johnston: And Bradford says “No” and…

Court Carney: Bradford says “No,” the Confederates assault the fort, and it is just very quick. I think there’s like two waves of soldiers on the Confederate side. They take it over really pretty quickly. You have a lot of hand-to-hand combat at this time. But then you also have, almost simultaneously, Union soldiers, black and white, fleeing toward the river. So as the Confederates are coming into the fort, a large number of Union soldiers, as they can, are racing towards the river because there is a gunboat there that they’re hoping can be protective of them. And so that’s the situation all throughout the late afternoon.

What happens after that is where things get really tricky. The massacre—what we would call the massacre—starts at some point in the late afternoon, after they have breached the fort and as people are trying to escape to the New Era—the New Era is the gunboat on the river. This is where we don’t have a real clear story of what happened. But we have a lot of bits and pieces that can tell us that you had people who had surrendered or were trying to surrender and were shot dead while surrendering. Most of these were black soldiers. Then you have all sorts of other stories coming out of people being lined up and executed. You have stories of that. You have stories of people being buried alive. You have stories of people being set on fire. And the scale here gets really murky. But you do have a real terrible hour or so were a fairly established series of atrocities committed by the white Confederates against primarily the black soldiers, but also the white Union soldiers that they found too.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressConfederate soldiers are depicted killing black Union soldiers who have surrendered at the Battle of Fort Pillow in an illustration published in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper on May 7, 1864.

Terry Johnston: Do we have any idea, even generally, what kind of numbers we’re talking about as far as those who were killed or were casualties? And were any actually captured and not killed by the Confederates?

Court Carney: You have some captured. Mostly the white soldiers are captured and they end up in Mississippi. We don’t have an exact number of how many men Forrest had. But, basically, the story as it gets written in the reports is that Forrest lost probably 14 people killed. And then dead on the Union side is somewhere around 220 or so. And if the numbers are correct and you have about 600 people in the fort, easily half of that group were either killed or wounded. And then others are able to escape or filter out or however it is. But you do have about 220 killed on the Union side where the Confederate total killed is 14. So it’s a mismatch throughout if you’re just looking statistically at the numbers. You do have some captured. You do have some people who escape. And this is where the news begins to spread. Because you then begin to see the stories coming out of the fort really pretty quickly.

Forrest, for his part, just moves on. His first report, and importantly Forrest writes two reports. He writes one report and then a second report once the news starts spreading. But the first report’s basically, like, “I went in there, I did what I was supposed to do, we moved on.” There’s a lot of pieces I’m not getting into that we’ll get into in a moment, but that’s an interesting piece of this: That from Forrest’s perspective, Fort Pillow didn’t really rise to the level of anything beyond what he was setting out to do. And then he moves on and the next day there’s something else, and the next day there’s something else.

Terry Johnston: Well, so then there is, as you said, a lot of coverage of this event pretty quickly after, not only in the press, but then there’s a rather sizable congressional investigation. What’s the coverage like, and what did the investigation really do?

Court Carney: So what’s interesting is that you have this growing news. First of all, for 1864, news is traveling really quickly. You have a Memphis newspaper, you have a Jackson, Mississippi, newspaper, a New Orleans newspaper. They start picking up on it. And this is where it’s really interesting. When I was doing a lot of the work on Forrest’s memory, this is really key, because you start looking at how the southern newspapers covered it. They are not covering it the way they will cover it. They saw it as slaughter. The word slaughter is used. Now, slaughter is not synonymous with massacre. But it’s interesting that there is not a regional sort of, “Oh, of course this was a good thing.” It’s not clear-cut. Southern newspapers were basically seeing this as a real bloody event, and they’re covering it that way.

But it hits the northern press soon after. There’s, I think, an Associated Press article. And then within several days of the battle, you start seeing the northern press come out and start using much more aggressive language: that this was butchery, that this was—I’m not exactly sure when the first use of the word massacre gets used, but it starts being used as an example of an atrocity. That part becomes part of the northern media landscape. Now, the southern landscape will change. The southern media landscape will cohere to sort of a, “This is a hard-fighting battle.” Not anything more than that. But early on it’s interesting. If you look at the early newspaper coverage, they aren’t saying the same thing. They’re saying this is a lot of uneven bloodshed.

So what happens is I think Sherman, maybe Grant, sends someone to look into it. And there’s a Union investigator out of, Cairo, Illinois, a guy named [Mason] Brayman, and he goes down and starts with a small group of people to investigate the claims. This is right after the battle, probably late April. And he is getting signed affidavits from people who were there claiming what they saw, the bloodshed, the wanton cruelty, all that kind of stuff. And his investigation says that there is clearly a violation of civilized war.

And this kind of gets us to our main question. But what Brayman does is that he starts collecting a lot of eyewitness accounts that then leads the Joint Committee on the Conduct of War in D.C. to open up an investigation. And this is all going on in May 1864. So, right after Fort Pillow. They don’t really wait on any of this.

Terry Johnston: And what do they find?

Court Carney: Well, they end up using some of these interviews and finding more interviews, and they ended up publishing the proceedings. One source that I really trust says it was kind of outlandishly published compared to other reports like this. But the report gets published pretty widely. Like they print up a large number of those reports. And the reports come down that this is clearly a violation, etc., etc., etc. Where it gets tricky, and where things get gummy for people who want a clear-cut case, is that you also have to understand Abraham Lincoln in this period, maybe late June or July, basically is trying to pivot to make sure that there’s no retaliation. One of the fears on the military leadership level was retaliation, that what would happen at Fort Pillow would then lead to retaliation from Union soldiers against Confederate soldiers, but more importantly, retaliation against the exchange of prisoners or even the keeping of prisoners. So, the backdrop of June and July, right after Fort Pillow, has a lot to do with prisoner and prisoner exchanges, which for the Confederacy was a pretty dire situation. So you have on top of the Fort Pillow story, the story of prisoner exchanges and what that’s going to do. And then on top of that you have Lincoln, who is not necessarily driven to create a vengeful war.

Terry Johnston: Yeah. Well, in essence, is that the answer to our original question as to why Forrest wasn’t charged with war crimes? Was it an unwillingness on the part of the administration or of military officials to escalate, as you said?

Court Carney: Yes. I think Fort Pillow, if it had happened at a different time, like if Fort Pillow had occurred in 1863, maybe it’d be different. You could make the argument that if Fort Pillow was, like, in Virginia, maybe that would’ve made a difference. But I don’t know if that’s necessarily true. I do think that there are two groupings of ideas as to why it doesn’t become more than this. Now, I will say that Forrest, for his part, uses it to his advantage. A lot of your listeners probably know that right after Fort Pillow you have the Battle of Bryce’s Crossroads in Mississippi, where you have Forrest versus black Union soldiers again, and they’re wearing “remember Fort Pillow” pins. So, you have that going on within the black Union soldier story, which I think is important. From Forrest’s perspective afterwards, he thinks Fort Pillow is useful to create his persona, and that’s going to then be useful if we talk later about the Ku Klux Klan and everything else.

Back to the story at hand. War crimes during the Civil War creates kind of an interesting question because on some level you have atrocities throughout the war. You have a story in Arkansas right after Fort Pillow, Poison Spring, which is in that same realm. But then you have, what does the Union do about it? And I think that there are a couple of non-Fort Pillow reasons here that are interesting. One, I think there is a fuzzy legal framework. From the Union perspective, it is not entirely clear-cut what defines a war crime and what we do about war crime.

Wikimedia

WikimediaHenry Wirz

You know, infamously, you have Andersonville and the commander of the prison in Andersonville will be the one—[Henry] Wirz—who will be executed for his involvement in what happened at Andersonville Prison. There’s a really great book, Andersonville in Memory, that was written by a scholar named Ben Cloyd. And Ben happens to be a friend of mine. I asked Ben about this and he summed it up by saying that Wirz was an outlier and an outlet. In other words, he was one of the rare cases we see an actual execution following these things. So, he’s an outlier. But he’s also an outlet by saying this sort of represents our form of military tribunal, war crime thing.

So, on one level, I think there’s a fuzzy framework, and this is coupled with the idea that I think you have a general lack of desire on the Union leadership side to follow through with some of this. And this goes to why we don’t see much against, like, Robert E. Lee. I mean there’s all sorts of things that happen to the Confederate leadership, but not to the level that might happen in different places in world history.

On another level, I think Fort Pillow creates a different set of questions. So you could say, well, maybe there’s not a strong legal framework here for the Union to say this is a war crime and therefore Forrest is a perpetrator of this. But you also have a lack of desire to really do it. But on the Fort Pillow side, you have the fact that there are enough inconsistencies that people could squint enough to say that maybe some of this stuff was not quite accurate. Now, I’m not saying that from my perspective. I’m saying that on the ground there were people who said that some of the affidavits were not truthful or there’s no way someone could have seen some of the stuff they witnessed seeing. That kind of thing. There’s also a question of intent. And this is a very important part. Did Forrest order any of this? And there’s a lot of pro-Forrest, pro Confederate voices that want to argue that Forrest clearly didn’t order this. And if he didn’t order it, then can he be held responsible for something that was clearly a very heated regional story of crossed boundaries and everything else.

And I think that this part’s interesting because when you say Forrest didn’t order it, you also have to then put into context Forrest using unconditional surrender and bluffing tactics his entire military career. I mean, throughout 1864, he’s bluffing that he has more men. Sometimes he does, sometimes he doesn’t. He’s bluffing that he’s got the high ground. Sometimes he does, sometimes he doesn’t. And so, Fort Pillow is not weird. He’s doing the same thing there he did other places. And the other part of it is, his soldiers knew the score. They knew what was up. They understood what was expected of them. So to say that there was no order is real, but in April 1864, there’s 15 other sort of things you could say that you don’t really need an order at this point for Forrest’s men to know what to do.

There’s a final point though, and this part I think is also incredibly important, and that is you had a fair amount of Union supporters, northerners, who were not all thrilled with the USCT [United States Colored Troops]. And they didn’t like the idea that you would have armed black soldiers from a northern perspective. And I think this is important to keep in mind that, later on, when we see the large death-after-surrender of black soldiers, that would be very appalling to a lot of people immediately after the Civil War. There’s a lot of people in the period that might not have found that as egregious because they had their own issues with that. And I think all of that blunts why Fort Pillow may seem very clear-cut in 1868 or in 1905 or something, but is far from clear-cut to people living through it in 1864.

Terry Johnston: Right. And it begs the question, if this happened, as you said earlier, in Virginia and those surrendering Union soldiers were white and not largely black, it would’ve been a different story as far as consequences and outrage and the like.

Court Carney: I think that’s true, and I think there’s something else too, that even at the time people were thinking that the northern press was latching on this for outrage. We’re outraged by this. And is that real outrage or is this outrage because it’s the war? I mean, that’s a very difficult time of the war. It’s difficult, certainly for the Confederacy, but it’s difficult for the North too. No one knows that it’s a year away from being over. It’s a real slog.

I think that then it’s like, well, are they just doing this because it’s now the new outrage that they’re using it for? Or is it something else? And I think all of these things go into where it’s just murky enough for there to be less of a clear-cut story. Now we could go further and talk about how pro-Forrest voices reframe this as a story of drunkenness, a story of black Union malfeasance, that they weren’t trained soldiers, that they were inebriated, that they were causing so many problems that forced the hand. But that’s a story of the 1870s and 1880s. Well after the battle, you start seeing the rise of the exonerating of Forrest. That Forrest was just a hard-hitting general and that he came upon a situation where the other side was not being gentlemanly.

Terry Johnston: Well, let’s move there because, as you say in your book, even though there was no official consequence, really, for his involvement with Fort Pillow, it did follow him. He was stigmatized—I think that was a word you used in your book—in the immediate postwar years. And this is where, as you were alluding to earlier, he uses his skills with the media to help bend the narrative. I’m thinking specifically of when you write about his involvement in the 1868 Democratic National Convention, where he is a delegate.

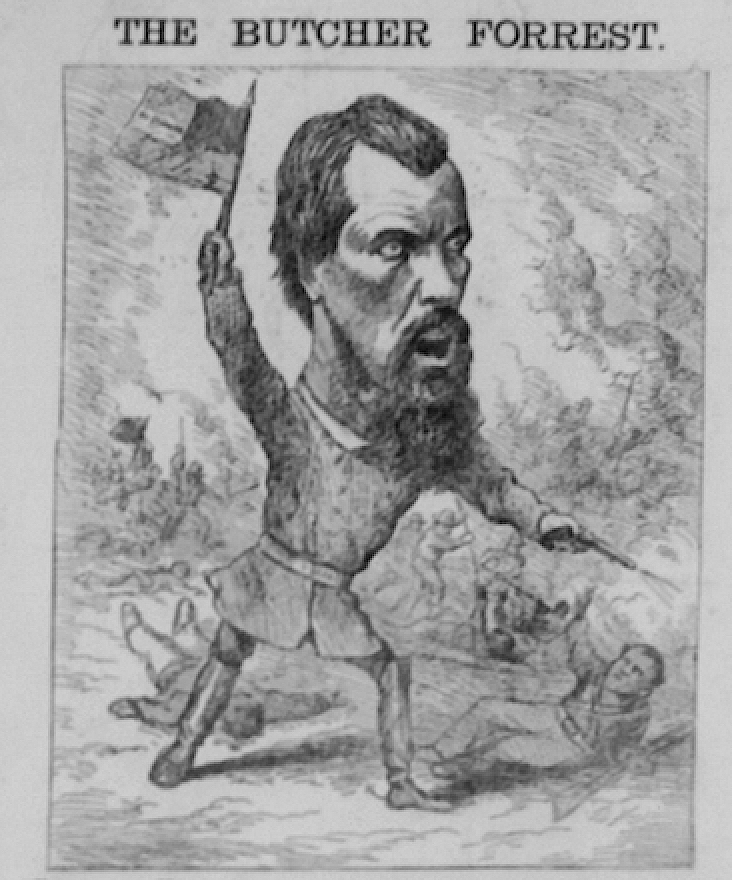

Library of Congress

Library of CongressThomas Nast’s 1868 political cartoon depicts “The Butcher Forrest” as one of the “Leaders of the Democratic Party.”

Court Carney: Right. That’s really important. Because when you get to 1868, he’s a delegate to the Democratic National Convention held in New York. And Thomas Nast does a series of very famous cartoons of him. What’s interesting is that a few years later, certainly in the 20th century, the thing that most people connect to Forrest is the Ku Klux Klan, which was present then. But he’s known much more by Fort Pillow. Nast is using Fort Pillow to define Forrest. Throughout this period, he is known as “the butcher” of Fort Pillow. All that stuff follows him. And I don’t ever get the sense that Forrest is annoyed by that. I think he uses that to his advantage of like, yeah, you know, I did that. He is not running away from it.

And in fact, by 1868 with New York, and then later on when they had the congressional hearings over the Klan, he is just spinning these stories. From a presentist standpoint, you could say, well, he’s not ever been held accountable. He gets a presidential pardon. So, he’s not really been held accountable for any of these actions, so why would he care at the end?

And the other thing about Forrest to keep in mind in the postwar period is that he is so actively trying to rebuild what he had that he is mostly interested in business contacts. He’s involved with insurance companies and railroad schemes, etc. So he’s much more interested in that. And if that gives him the cache in the white southern business world, then he’ll use it. But all that said, he is definitely not hurt by any of this. From the North he becomes “the butcher” of Fort Pillow. But to the South, that just doesn’t rise to a real level for them.

Terry Johnston: Right. And as you say, he never really did admit any kind of wrongdoing. Quite the opposite. And this gets back to his media savvy and his friends in the press. They started to question the veracity of some of the wartime accounts of Fort Pillow, right?

Court Carney: Right. And then there’s a biography of him that comes out. It’s the only book about his life that comes out during his life. So we know that he at least has some, maybe not say over it, but he clearly was not appalled by it. And that sort of exonerates the whole thing. And it’s just sort of dismissed.

And the other part is when he’s called to testify for the Klan, he says a lot of things that are sort of truthful and then he is saying other things that are not. And it’s kind of a blend. But he has this quote afterwards where he tells a friend, “I lied like a gentleman.” Like he knows how to play this game and he is giving Congress exactly what they think they’re wanting, but he is not giving them enough to really do him in.

And then the other thing that happens with Forrest is that he dies not long after the war. He dies in 1877, before there’s any real, what we’d see as a Lost Cause movement, or anything like that. So his whole story is definitely on a different trajectory from others.

Terry Johnston: Well, I think you’ve taken us through pretty comprehensively. Is there any other element to this that you think we should discuss?

Court Carney: When I think of Fort Pillow now, what I really think about is the fact that the survivors of Fort Pillow, the black survivors of Fort Pillow, many of them end up moving on and having to restructure their lives. But there is a handful of black men who fought at Fort Pillow, who witnessed all of this, and then two years later are there in Memphis during the race riots there, where they’re again facing so much brutality. And I think that we can lose sight of the fact that Fort Pillow, though it may not rise to the level of an enforceable war crime, has a human cost where you have these individuals who—Fort Pillow had to have stayed with them for some time. And there’s another human cost. Booth, who’s killed early in the battle, his wife actually ends up pushing very hard for pension rights for widows. And so you could trace the move to get more pension rights for the widows of people who lost their life in the war to Fort Pillow too. So you have this cloud of memory. Fort Pillow is not something that ends in April 1864 for some of these people.

And then you have this real narrative of standing there today and going, this doesn’t even make sense to me. And I think that is a reminder that the Civil War is so distant in some ways, and yet you’re standing right on the ground where it happened. And I think that distance is an important one—certainly for scholars and people interested in it from the intellectual, academic perspective, but also just people who want to visit these sites—in realizing how far and how close all of this really is when you’re standing there.

About the Guest

Court Carney is a professor of history at Stephen F. Austin State University and the author of Reckoning with the Devil: Nathan Bedford Forrest in Myth and Memory (LSU Press, 2024).

Court Carney is a professor of history at Stephen F. Austin State University and the author of Reckoning with the Devil: Nathan Bedford Forrest in Myth and Memory (LSU Press, 2024).

Additional Resources

- Charles Royster, The Destructive War: William Tecumseh Sherman, Stonewall Jackson, and the Americans (1993)

- Lionel F. Booth

- Benjamin G. Cloyd, Haunted by Atrocity: Civil War Prisons in American Memory (2016)