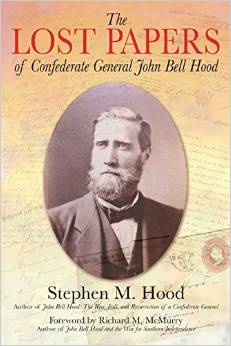

The Lost Papers of Confederate General John Bell Hood edited by Stephen M. Hood. Savas Beatie, 2015. Cloth, ISBN: 978-1-61121-182-5. $32.95.

In 2012, author Stephen M. Hood revealed the existence of a trove of documents belonging to John Bell Hood—documents long assumed to have been lost to history. In fact, the papers had been dutifully preserved by descendants of the Confederate general, one of whom brought them to the attention of Stephen Hood (himself a collateral descendant) while he was writing John Bell Hood: The Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of a Confederate General. Mr. Hood (as I will refer to him to distinguish him from Gen. Hood) incorporated those papers into his vigorously argued defense of his kinsman. Two years after that book’s publication, Mr. Hood now presents an edited and annotated volume containing most of those papers, offering them to the public both as a means to better understand John Bell Hood’s life and career, but also as fresh evidence to support his ongoing defense of the general’s reputation.

In 2012, author Stephen M. Hood revealed the existence of a trove of documents belonging to John Bell Hood—documents long assumed to have been lost to history. In fact, the papers had been dutifully preserved by descendants of the Confederate general, one of whom brought them to the attention of Stephen Hood (himself a collateral descendant) while he was writing John Bell Hood: The Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of a Confederate General. Mr. Hood (as I will refer to him to distinguish him from Gen. Hood) incorporated those papers into his vigorously argued defense of his kinsman. Two years after that book’s publication, Mr. Hood now presents an edited and annotated volume containing most of those papers, offering them to the public both as a means to better understand John Bell Hood’s life and career, but also as fresh evidence to support his ongoing defense of the general’s reputation.

The Hood Papers are organized into topically themed chapters, covering such subject matter as the Atlanta Campaign; the 1864 Tennessee Campaign; medical reports pertaining to the treatment of Gen. Hood’s Gettysburg and Chickamauga wounds; and letters to his wife, Anna Marie Hood. Many of the letters most eagerly sought by historians were those written to Hood after the war by Confederate comrades in preparation for his memoir, Advance and Retreat. Stephen Hood has done yeoman’s work editing and annotating the documents for this collection. His chapter introductions and commentary provide a solid foundation for understanding various aspects of the general’s life and career. Mr. Hood helpfully provides concise and often detailed biographical footnotes for virtually every correspondent appearing in the papers, from well-known figures like Jefferson Davis and Braxton Bragg to more obscure individuals, such as Francis A. Shoup, Hood’s chief of staff while commanding the Army of Tennessee. Topically, The Lost Papers cover some areas of Hood’s Civil War career more than others. Readers will find more documents pertaining to his service in the West than in Virginia, and more relating to the Battle of Franklin than the Battle of Atlanta. This, of course, reflects the nature of the document collection itself and not their publication.

Although The Lost Papers can stand alone as a published document collection, the book can perhaps best be understood as a companion and follow-up to Mr. Hood’s John Bell Hood: The Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of a Confederate General [2013], also published by Savas Beatie. Just as Gen. Hood collected many of these documents in order to justify and defend his reputation in Advance and Retreat, so too does Stephen Hood present The Lost Papers as the next round in an ongoing defense of his kinsman’s reputation. Recent decades have witnessed passionate debates over various legends and controversies attached to John Bell Hood. Did he conspire to oust Joseph E. Johnston from command of the Army of Tennessee? Was Hood’s judgment as a commander impeded by a supposed addiction to opiates after losing a leg at Chickamauga? Does fault for the Union escape at Spring Hill lie with Hood, or his subordinates? How reliable is Advance and Retreat?

Mr. Hood clearly expects that these newly publicized documents will redeem the general’s reputation on all fronts, and the papers do in fact seem to buttress a number of claims by the general’s defenders. Perhaps most decisively, the medical reports by Dr. John T. Darby seem to belie the legend of John Bell Hood the laudanum addict. After the general’s right leg was amputated at Chickamauga, the surgeon recorded giving Hood small doses of “morphia”—as a sleep aid, rather than a painkiller. Within a week after the battle, it seems Hood was declining further doses as no longer necessary. Furthermore, while numerous Civil War histories have described Hood’s Gettysburg wound as rendering his left arm “useless” and paralyzed, Dr. Darby’s reports reveal that Hood possessed substantial use of his arm and hand.

In other cases, however, some documents do not prove Mr. Hood’s case as conclusively as he suggests. Consider the debate over whether, as a result of the Spring Hill incident, Patrick Cleburne went to his death at Franklin believing he had been unjustly censured by Gen. Hood, or, as Mr. Hood surmises, “felt deep remorse and vowed that he would never again disobey orders” (114). A. P. Stewart offered the latter explanation to Stephen D. Lee, who described their conversation on the matter to Hood in an 1875 letter. Of course, we must weigh this claim with accounts outside of the Hood Papers, such as John C. Brown’s 1881 letter asserting that Hood had left Cleburne feeling “angry” and “deeply hurt.”[1]

One must remember that the Hood Papers represent a collection of documents assembled by the general himself in part for the purpose of substantiating his side of the story. In 2012, William C. Davis presciently surmised that many of the letters would “be from people who were friends and associates most likely to support his version of events. That is the way with all memoirs, alas.”[2] That is not to say that the documents are inherently wrong or untrustworthy, but rather that they, like any other primary documents, must be handled with a critical eye.

To his credit, Stephen Hood does not limit the historical value of the Hood Papers to their ability to redeem the general’s reputation. As he astutely observes, the medical record not only helps to clarify the nature of Gen. Hood’s medical condition, but also provides an incredibly detailed and sometimes graphic glimpse of Civil War medicine. Amongst Hood and his fellow ex-Confederates, we find speculation of renewed hostilities between North and South, such as the following from Francis Shoup: “The last war settled nothing…. Every day opens the country for the new struggle” (58). The Lost Papers will also introduce readers to postwar allies and friends of Hood, not the least being William Tecumseh Sherman who, in 1879, penned a heartfelt letter of condolence following Anna Hood’s passing due to yellow fever.

Stephen Hood strongly believes The Lost Papers will vindicate John Bell Hood in the various debates surrounding the general’s military career. The extent to which the documents will accomplish that purpose lies in the minds of individual readers. With more certainty, one can say that this collection provides more grist for the mill in ongoing efforts to better understand the life and times of one of the Civil War’s most controversial generals.

Jonathan M. Steplyk received his Ph.D. in History at Texas Christian University, where his is currently an adjunct instructor, and has also worked as a seasonal ranger at Cedar Creek and Belle Grove National Historical Park.

[1]Quoted in Eric A. Jacobson and Richard A. Rupp, For Cause and for Country: A Study of the Affair at Spring Hill and the Battle of Franklin (Franklin, TN: O’More Publishing, 2008), 192-93.

[2]Quoted in Kraig McNutt, “Why is the Recent Discovery of the John Bell Hood Papers and Documents Important and Why Should You Care?” BattleofFranklin.net, entry posted November 3, 2012, https://battleoffranklin.wordpress.com/2012/11/03/why-is-the-recent-discovery-of-the-john-bell-hood-papers-and-documents-important-and-why-should-you-care/ (accessed May 15, 2015).