On a late October morning in 1862 the U.S. Treasury department received a visit from Robert J. Walker. The former Mississippi senator was something of an enigma in war-torn Washington—an adoptive southerner and architect of the antebellum free trade movement, a staunch unionist, and an anti-slavery man who believed in gradual emancipation. Walker was no stranger to the Treasury department, having previously served at its helm under President Polk. In 1857 James Buchanan appointed him Governor of the Kansas Territory—a position he soon resigned in protest against the pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution. As with many southern moderates of the previous generation, Walker had long advocated the gradual elimination of slavery by way of colonizing the former slaves abroad in Liberia, and such was the purpose of his visit.

The Treasury department clerks listened attentively as Walker read a passage from his latest composition, an article set to appear in the upcoming issue of the Continental Monthly. He praised President Lincoln’s own embrace of colonization as a means of placing slavery on the path to extinction and offered approving words for a project, recently announced, to settle freedmen on the Central American isthmus. Yet Walker had come to press the administration on Liberia, the small republic founded by American ex-slaves on the eastern coast of Africa and a favored resettlement locale of its patron organization, the American Colonization Society. “Liberia has already contributed to the decline of the African slave trade,” he continued reading. “Let us purchase for Liberia the great adjacent coast and interior of Africa” as both a home for the freed slaves of the impending Emancipation Proclamation and a strategic foothold in the region. “Liberia would thus expand and become the great Afric-American Republic, and the dominant nation of that immense continent.” This was Manifest Destiny writ large and a “moderate” solution to the slavery problem all in one.1

Abraham Lincoln was no stranger to colonization or Liberia. “My first impulse,” he stated in his famous Peoria address of 1854, “would be to free all the slaves, and send them to Liberia, to their own native land.” In 1862 he extended diplomatic recognition to the African nation. Along with Haiti it was the first majority-black government to receive this acknowledgement and the president’s diplomacy was at least in part motivated by the potential for each to receive black settlers.

Indeed Lincoln’s first legislative strike against slavery seemed to anticipate a Liberian colonizationist corollary. On April 17, 1862—one day after signing the District of Columbia Emancipation Act, which included $100,000 for resettlement purposes—the president met with Alexander Crummell and J.D. Johnson, two African-American “emigration commissioners” acting on behalf of the Liberian government. Per Johnson’s recollection, Lincoln indicated he “would be glad to put the money appropriated by congress” toward Liberia. No further plans came of the meeting though, and the government quickly turned its sites elsewhere. “The expense of colonizing Liberia,” noted Interior Secretary Caleb B. Smith, “would be greater than at any other point named” with transit costs far exceeding nearby Panama. Furthermore the Colonization Society—a likely partner in any Liberian venture—had yet to provide any substantial list of prospective emigrants, whereas the isthmian scheme’s backers claimed a population of recruits ready to sail.2

Walker’s October visit caught the attention of Donald MacLeod, a bookkeeper in the Treasury Department and Colonization Society supporter in his own right. In a week’s time MacLeod would have an opportunity to press the Liberian case with Abraham Lincoln directly. He called upon the president on October 23 with a paper in hand from a Colonization Society official, espousing Liberia’s strategic advantage of an established government. The president then “read the letter and the extract with attention, and turning to me, said with great emphasis”:

I am perfectly willing that these colored people should be sent to Liberia, provided they are willing to go, but there’s the rub. I cannot coerce them if they prefer some other locality. Central America was designated because they showed a willingness to go there. But I would just as soon, and a little rather, send them to Liberia. But where are the people who wish to go there?

MacLeod then suggested converting Senator Samuel Pomeroy of Kansas to the project. As the official agent of the competing scheme to settle the Chiriqui region of Panama, Pomeroy purported to have a list of several thousand persons ready to emigrate, although its reliability was in doubt and persistent rumors of his corruption had combined with opposition from other Central American governments to place that project on hold. Signifying his openness to other options, Lincoln authorized MacLeod to share the contents of their conversation. “You may say that I will aid them with all the means in my control to send these people to Liberia, provided they are willing to go.”3

The next morning MacLeod conveyed the president’s message to Rev. Ralph R. Gurley, secretary of the Colonization Society. To MacLeod’s surprise the longtime promoter of Liberian colonization responded with caution. The Society’s board was reluctant to become involved with the transport of “contrabands”—those slaves freed as a product of northern military movements —in the event that their former masters might try to reclaim their “property” should the Confederacy emerge victorious from the raging Civil War. Gurley was nonetheless willing to seek former slaves from the District of Columbia under its separate emancipation laws.

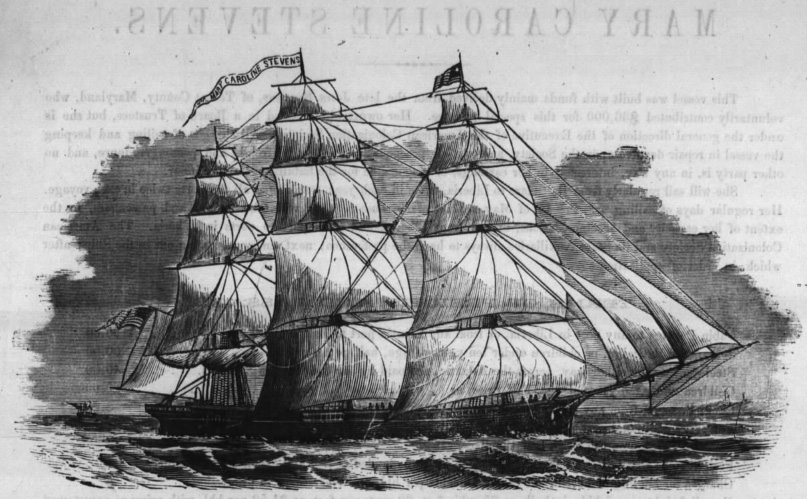

The turn of Lincoln’s interest toward Liberia nonetheless quickly spread through the Colonization Society’s state chapters, with one agent from Pennsylvania sending his gratification to Gurley: “Our part now is to get the emigrants.” Prompted by Gurley, George W. Samson of the Society’s New York chapter proceeded to the White House on November 1 with the object of introducing the president to Rev. Chauncey Leonard, the African-American pastor of Washington’s 19th Street Baptist Church. With the offer of federal funding on the table, Leonard proposed an investigative mission to Liberia in order to report back upon its suitability for colonization to the black residents of the District. Before they departed Lincoln announced that “he could have 50” settlers ready to emigrate by the next sailing of the Mary Caroline Stevens, a Colonization Society-owned transport vessel based in Baltimore. The following day Caleb Smith offered to supply $100 per emigrant passenger.4

Curiously, the same afternoon a delegation of nine African-Americans who had signed on to Pomeroy’s stalled Panama venture appeared at the White House to press for the project’s resumption. Perhaps signaling a shift in preference toward Liberia, Lincoln’s secretary John G. Nicolay replied that the president “could not now see the deputation” though he “was anxious as he ever was for their departure” to a suitable locale. Within a month’s time several members of this delegation had signed on to the Colonization Society’s next packet to Liberia and its leader, the black abolitionist poet John Willis Menard, had been hired as a clerk in the Interior Department’s colonization office.5

True to his promise, Lincoln met with Leonard and another Colonization Society agent on January 30, 1863, and provided the pastor with passage on the brig Samuel Cook, departing for Monrovia a week later. With this presidential nod of approval, the government’s offer to direct settlers to Liberia showed initial promise as well. James Mitchell, the president’s colonization commissioner, provided Gurley with a list of 160 names to be financed from the colonization account and Menard, the African-American poet turned emigrationist, offered to recruit and lead a group of settlers from the freed slave “contraband camps” around Washington and Fortress Monroe in Virginia.6

By late May though, administrative infighting in Lincoln’s cabinet combined with the Colonization Society’s cautionary conservatism to scuttle the plan. In addition to bureaucrats jockeying for control of the government’s sizable colonization account, one culprit was a lingering cloud of suspicion within the African American community. Many blacks justifiably questioned the wisdom of placing their funding and futures in the hands of a white colonizationist organization whose motives and sometimes strained relationship with the Liberian government had long spawned distrust. J.D. Johnson, the Liberian emigration agent, informed Lincoln in April 1863 that “many freed persons are now waiting to go” but “not under the care of the American Colonization Society.” He suggested an alternative arrangement administered directly by Mitchell in partnership with the Liberian government in its stead.7

Little else came of Robert Walker’s visions for a broad American imprint on the African coast, and Lincoln’s attention shifted elsewhere even as he clung to colonization beyond the point that many historians acknowledge. Plagued by emigration speculators of widely varying repute, the president turned in early 1863 to partnerships with the “stable” powers of Great Britain and the Netherlands to attempt the colonization of their Caribbean holdings. When the Mary Caroline Stevens finally set sail for Monrovia on May 25 she carried only 26 passengers, including but one single family that qualified for the promised federal subsidy. The prospect of a Liberian partnership with the American government quietly withered away, becoming a little-known “path not taken” in our complex and intertwined histories.8

Phillip W. Magness, PhD, is the Academic Program Director at George Mason University’s Institute for Humane Studies. He currently teaches at GMU’s School of Public Policy and, along with Sebastian N. Page, is the co-author of Colonization after Emancipation: Lincoln and the Movement for Black Resettlement (University of Missouri, 2011).

1 Robert J. Walker, “The Union,” Continental Monthly, November 1862.

2 Annual Report of the Board of Managers of the Massachusetts Colonization Society of May 28, 1862 (Boston: T.R. Marvin & Son, 1862); Abraham Lincoln to Johnson and Crummell, May 5, 1862, reprinted online at http://philmagness.com/?page_id=407; Department of the Interior, African Slave Trade and Negro Colonization Records, RG 48, M 160, National Archives and Records Administration; Domestic Letterbooks and Annual Reports for 1863-4, American Colonization Society Papers, Library of Congress.

3 Diary of Donald MacLeod, MacLeod Family Papers, Virginia Historical Society.

4 Domestic Letterbooks, American Colonization Society Papers, Library of Congress.

5 Sebastian N. Page, “Lincoln and Chiriqui Colonization Revisited,” American Nineteenth Century History, Vol. 12-3, October 2011 ; “Negroes Anxious to Emigrate,” Springfield Daily Republican, November 2, 1862.

6 Domestic Letterbooks and Annual Reports for 1863-4, American Colonization Society Papers, Library of Congress.

7 Department of the Interior, African Slave Trade and Negro Colonization Records, RG 48, M 160, National Archives and Records Administration.

8 “Departure of the Mary Caroline Stevens on her Eleventh Voyage to Liberia.” The African Repository, June 1863.

Illustration courtesy of the author.