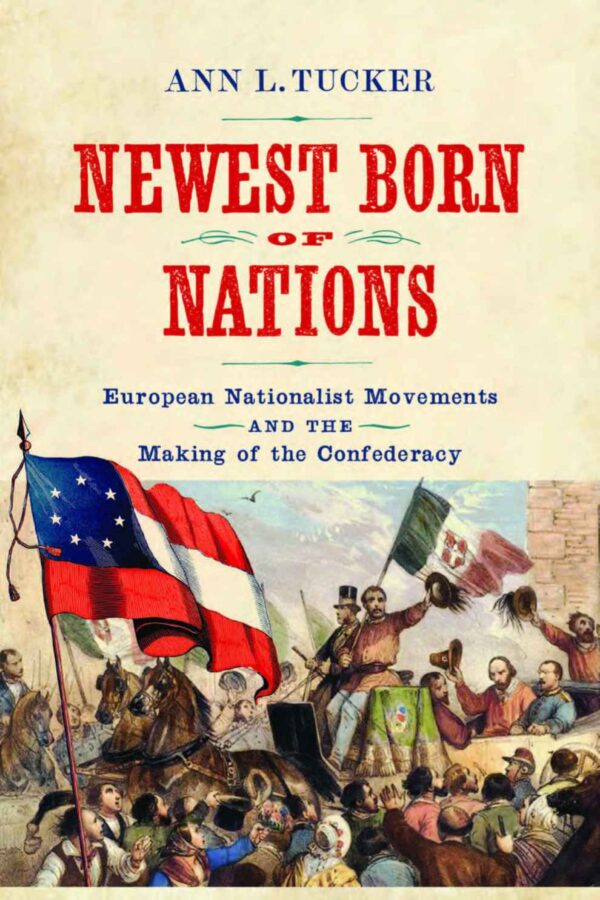

Newest Born of Nations: European Nationalist Movements and the Making of the Confederacy by Ann L. Tucker. University of Virginia Press, 2020. Cloth, ISBN: 978-0813944289. $45.00

Paul Quigley has written that white Southerners “often placed the American nation in international context” (Quigley, Shifting Grounds, 7). Ann L. Tucker, a former student of Quigley’s, describes how southerners defined themselves in an international context in Newest Born of Nations: European Nationalist Movements and the Making of the Confederacy. She writes that white southerners drew from two political ideologies: liberalism, the idea that people had rights that governments should protect, and conservatism, the idea that social order and structure should be conserved even at the cost of individual rights (9). Drawing on these larger political traditions, southerners were divided into two competing international perspectives: the liberal perspective saw the Confederacy as emulating the nationalist movements of Europe, while the conservative perspective saw the Confederacy as a purifying force against the excessiveness of contemporary global nationalist movements (10-11). Tucker briefly touches upon a third, Unionist perspective and the ways in which these southerners sought to situate their continued allegiance to the Union within an international context (3).

Paul Quigley has written that white Southerners “often placed the American nation in international context” (Quigley, Shifting Grounds, 7). Ann L. Tucker, a former student of Quigley’s, describes how southerners defined themselves in an international context in Newest Born of Nations: European Nationalist Movements and the Making of the Confederacy. She writes that white southerners drew from two political ideologies: liberalism, the idea that people had rights that governments should protect, and conservatism, the idea that social order and structure should be conserved even at the cost of individual rights (9). Drawing on these larger political traditions, southerners were divided into two competing international perspectives: the liberal perspective saw the Confederacy as emulating the nationalist movements of Europe, while the conservative perspective saw the Confederacy as a purifying force against the excessiveness of contemporary global nationalist movements (10-11). Tucker briefly touches upon a third, Unionist perspective and the ways in which these southerners sought to situate their continued allegiance to the Union within an international context (3).

Organized chronologically, Tucker’s work is persuasive and easy to follow. Part I, “Age of Revolutions, 1820-1850” sets the international stage and situates the U.S. South within an international context. During this nationalistic era, southerners seemed to be motivated primarily by conservatism. Whether conservative or liberal, however, white southerners agreed that republicanism, “self-government, and national self-determination” were the central values that a nation should possess (19).

The book’s second part, “Antebellum Sectionalism, 1850-1860,” more closely examines the South and the ways international perspectives created a powerful sectionalism within the United States. Southerners’ “use of an international perspective,” Tucker argues, “to analyze the sectional issues of the 1850s ultimately encouraged and enabled them to conceive of the South as distinct from the North on issues of nationhood, paving the way for the idea of an independent southern nation” (40). Without an understanding of the contemporary nationalistic movements across the globe, southerners would not have been equipped to conceive of themselves as a national unit. As the South compared themselves to other nations, they became equipped to “translate their concerns about slavery into internationally-acceptable language” (43). Indeed, the desire to protect slavery was the motivating factor of conservative southern internationalism; threats to slavery were equated to the tyranny of excessive liberal European nationalist movements (47, 74).

Part III, “Secession, 1860-1861,” zeros in on the secession crisis and how conservatives, liberals, and Unionists either supported or opposed secession using an international perspective. The liberal perspective was largely an emotional appeal to the values of the American Revolution, claiming that secession would protect southern rights (95-97). The conservative defense of secession emphasized the South’s uniqueness among other nations and was motivated by a fear of excess liberalism, manifested in democracy and social equality; conservatives were aiming to build a nation based on racial hierarchy and social order (115, 119). Finally, Unionists “highlighted the horrors of national division and confirmed their overall position that the white South was not oppressed by the North” (136). Unionists did not disagree with the content of liberal and conservative southern internationalisms; instead, they disagreed on securing southern rights and order.

The final part of Tucker’s book, “Wartime Realities, 1861-1865,” describes the ways southerners remained loyal to their international perspective despite the headwinds of wartime realities (158). Tucker especially examines the ways southerners of all three international traditions dealt with the harsh realities of lack of foreign recognition and defeat.

Tucker’s analysis is insightful. Historians Paul Quigley and Andre Fleche have demonstrated the importance of a transnational perspective in understanding southern and American nationalisms. Tucker fills a historiographical void by describing exactly how southerners looked abroad to support their own cause.

Newest Born of Nations fits southerners into three neat categories (liberal, conservative, and Unionist). This reviewer would have appreciated more discussion of how the three perspectives interacted with each other. Tucker herself writes that conservative and liberal internationalisms “were often two sides of the same coins, with southerners claiming that their liberalism was superior because it was tempered by conservatism” (117-18). A more in-depth analysis of how these internationalisms related and interacted with each other would have been welcome. Nonetheless, Tucker has made a valuable contribution to our understanding of how white southerners conceptualized themselves before and during the Civil War.

Caleb W. Southern is a graduate student in the Department of History at Sam Houston State University.