Between June 25 and July 1, 1862, George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac and Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia battled on the outskirts of Richmond. The fate of the capital of the Confederacy lay in the balance. A decisive Union victory could have resulted in the capture of Richmond—and likely the end of the rebellion. But Lee’s outnumbered Rebels outperformed their opponents during the week-long series of engagements—known to history as the Seven Days Battles—driving Union forces away from Richond. Below are images that help tell the story of the fateful week of fighting.

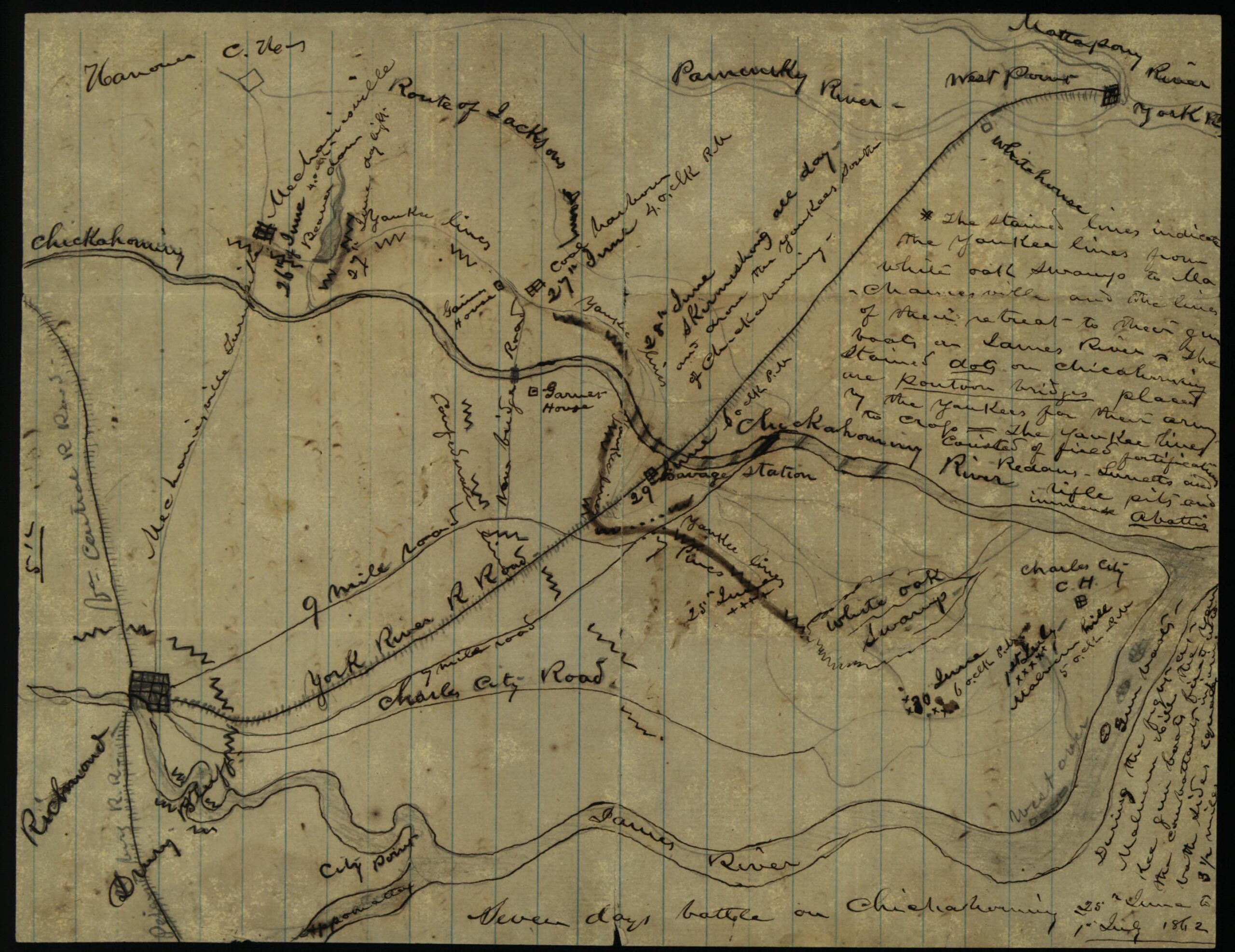

The Seven Days Battles began on Wednesday, June 25, 1862, with the minor fighting at Oak Grove, where McClellan’s advancing army attacked Confederate troops in hopes of moving closer to Richmond. Darkness ended the fighting, which produced slightly over 1,000 total casualties. Shown here is a pen and ink map of the campaign made shortly after the battle. (Library of Congress)

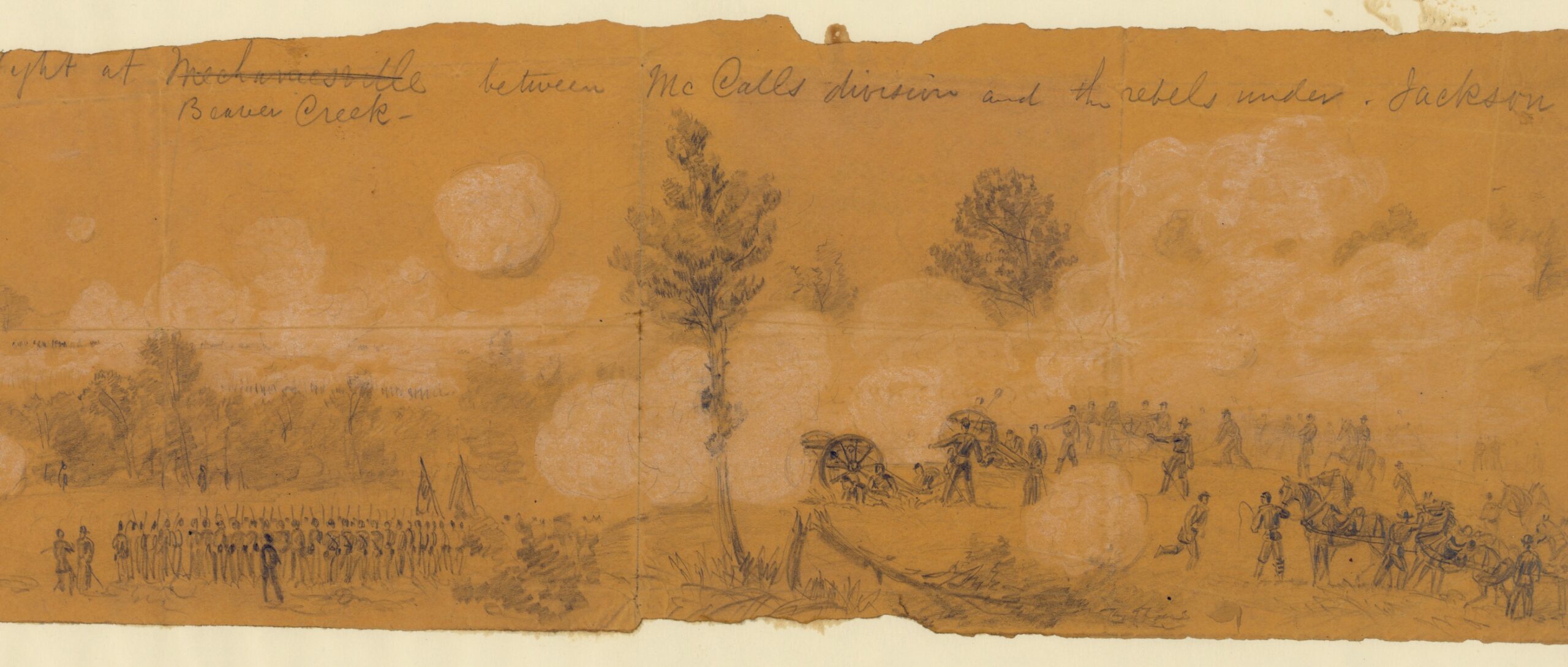

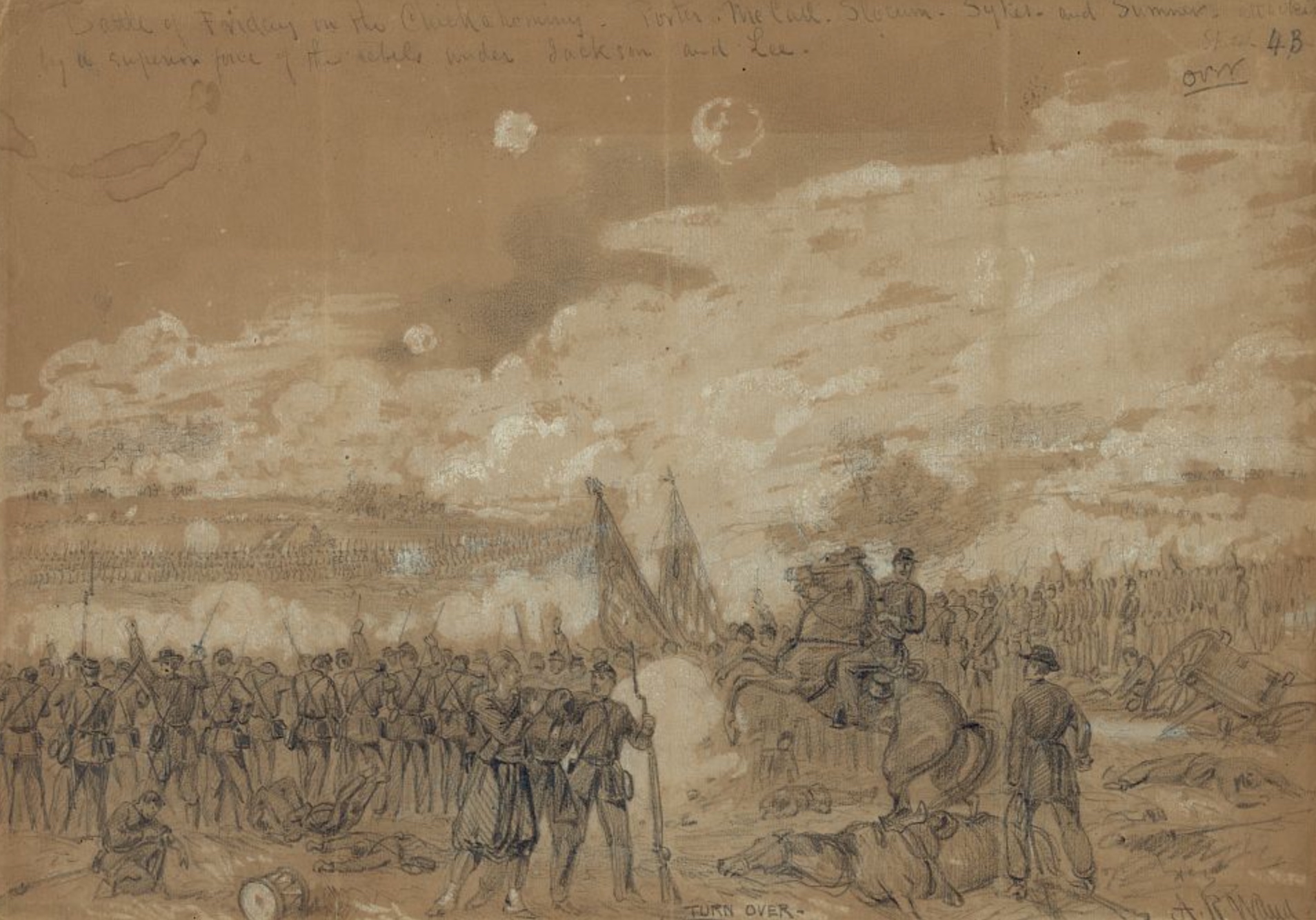

More significant fighting occurred the following day, June 26, at Beaver Dam Creek, where Lee sent troops under Stonewall Jackson to attack and turn the Union right flank north of the Chickahominy River while troops under A.P. Hill assaulted the Union line to the west. War artist Alfred Waud made this sketch of the fighting, a version of which would be published in Harper’s Weekly. (Library of Congress)

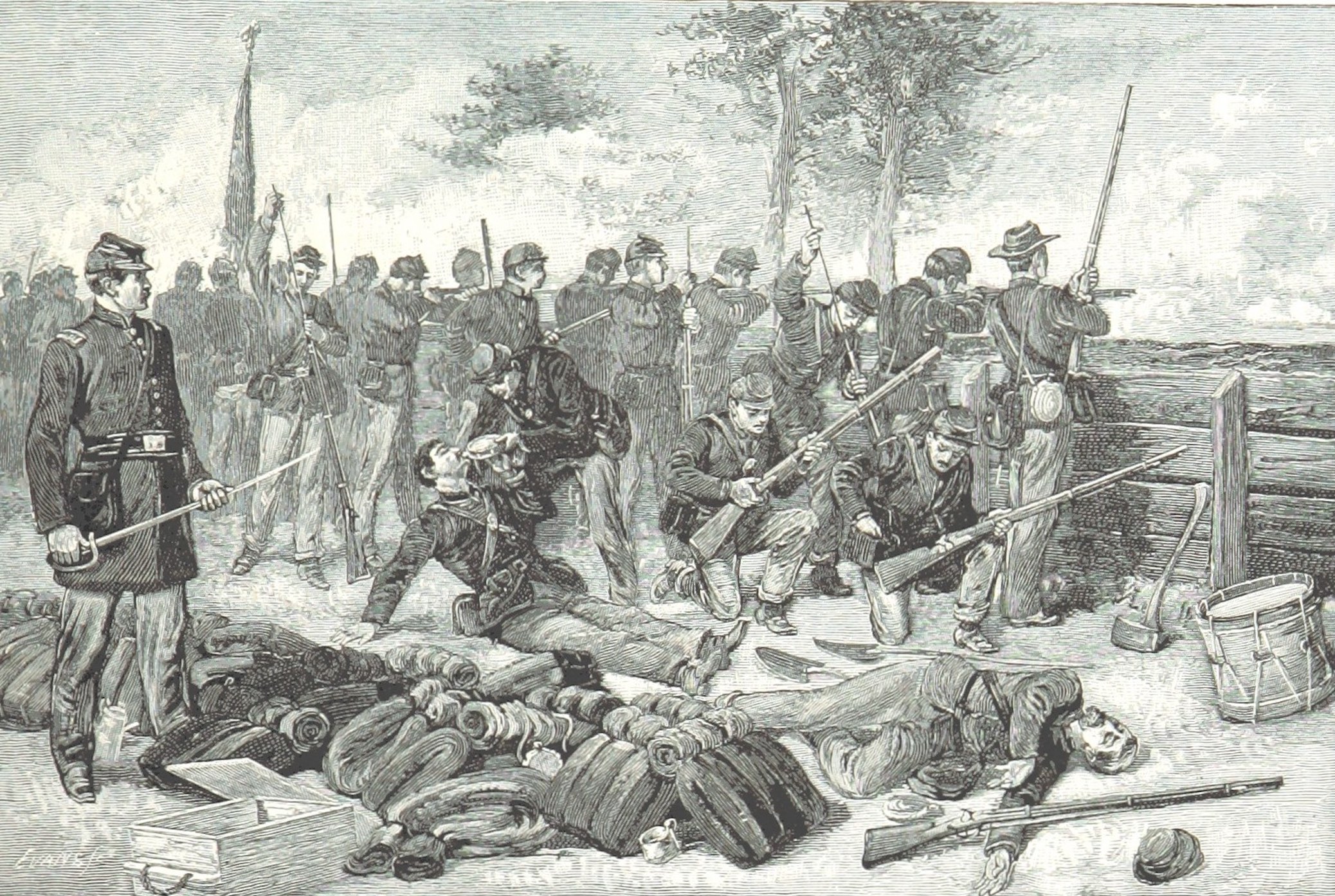

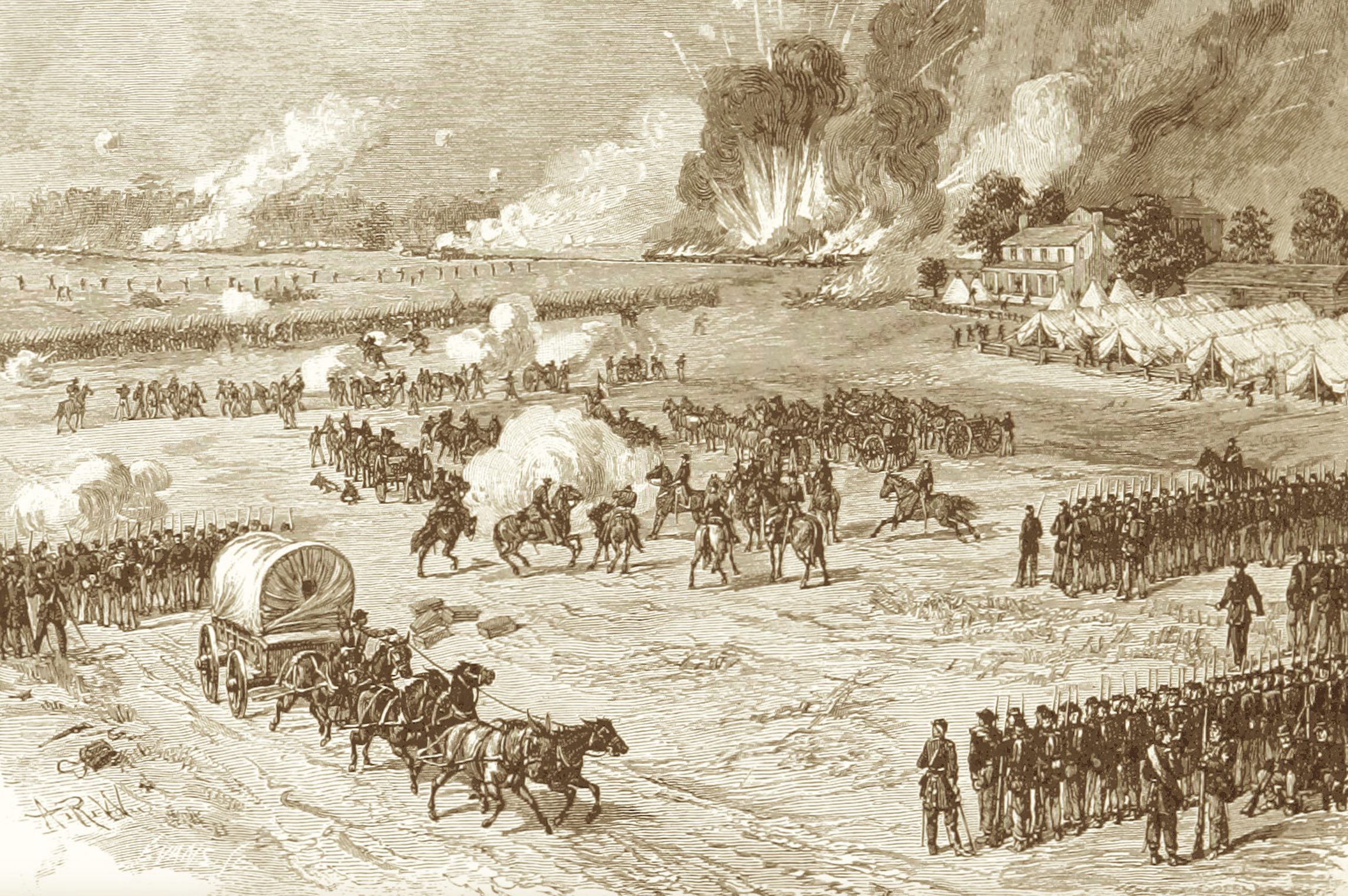

Lee’s plans soon went awry, as Jackson’s men failed to attack on schedule. Hill’s men went ahead with their assault against Union troops stationed outside Mechanisville (including these at Ellerson’s Mill depicted in a postwar illustration). While the fighting resulted in a tactical Union victory and significant Confederate causalties, McClellan elected to withdraw his army to the southeast, forfeiting the initiative. (Battles and Leaders of the Civil War)

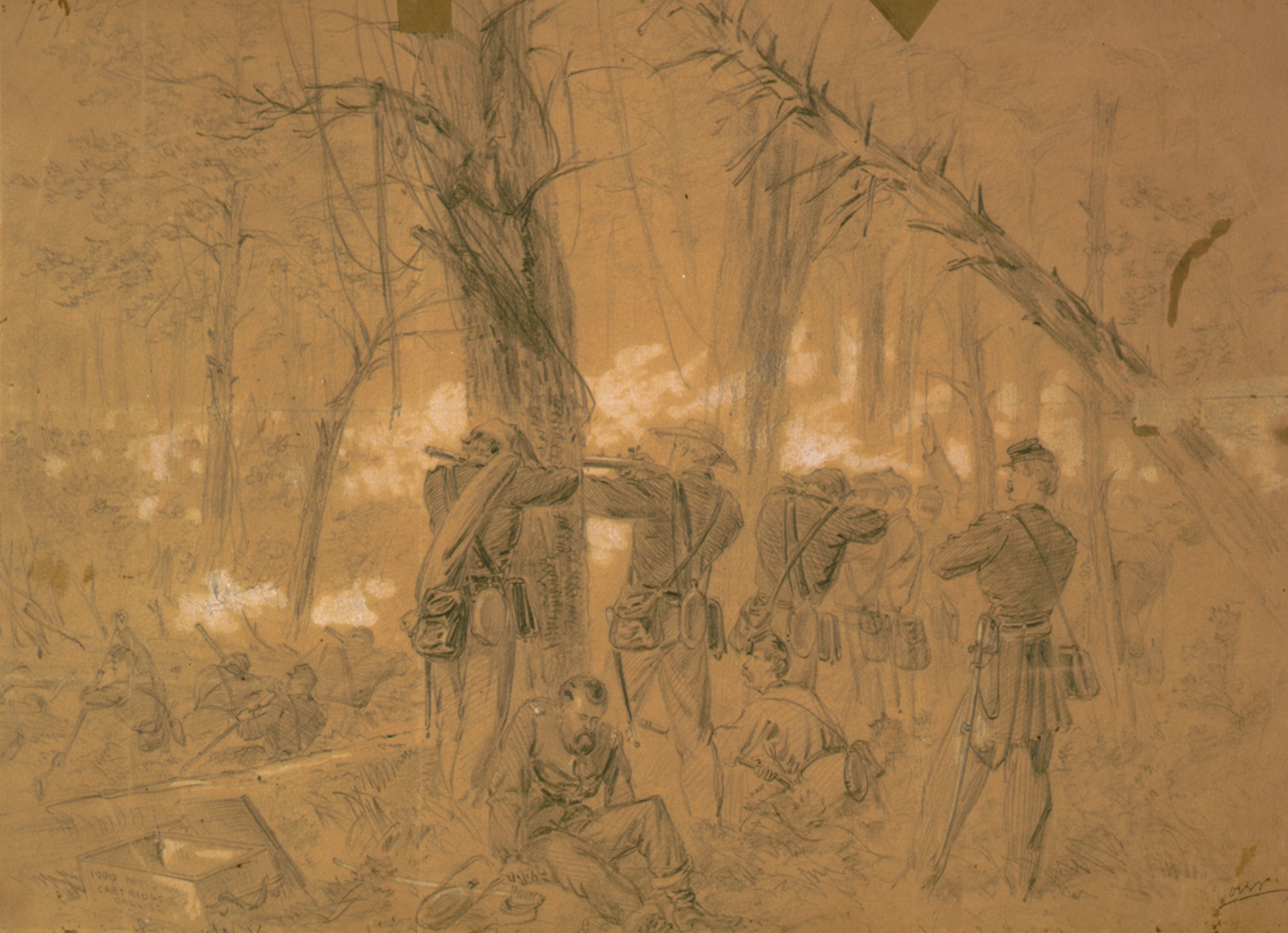

Lee continued his offensive against the Union army’s right flank on June 27, launching what was the largest Confederate attack of the war against the lines of Fitz John Porter’s Union V Corps at Gaines’ Mill. The repeated Rebel assaults finally forced Porter back toward the Chickahominy River around dusk. This Waud sketch captures the intensity of the day’s fighting. (Library of Congress)

While Lee’s men suffered slightly higher casualties than their opponents, the Battle of Gaines’ Mill was a decisive Confederate victory, one that convinced McClellan to abandon his campaign for Richmond and begin a retreat toward the James River. In this sketch, Confederate troops are shown advancing to capture abandoned Union guns at Gaines’ Mill. (Library of Congress)

After a day of minor fighting at Garnett’s & Golding’s Farm, the Union and Confederate armies clashed again on June 29 at Savage’s Station. Throughout the day, Lee’s Confederates clashed with elements of the rearguard of the retreating Union army. Contrary to Lee’s hopes of catching and destroying th Army of the Potomac, the fighting (shown here in a postwar illustration) proved inconclusive. (Battles and Leaders of the Civil War)

While the fighting at Savage’s Station produced approximately 1,500 total casualties, some 2,500 previously wounded Union soldiers (some of them shown here) convelescing at field hospitals in the area were left by the retreating Army of the Potomac to be captured by the Confederates. (Library of Congress)

The retreating Army of the Potomac (shown here in a wartime depiction) stretched over miles. By noon on June 30, about one-third of its men had reached the James River, while the remainder were still on the move between White Oak Swamp and Glendale. (Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection)

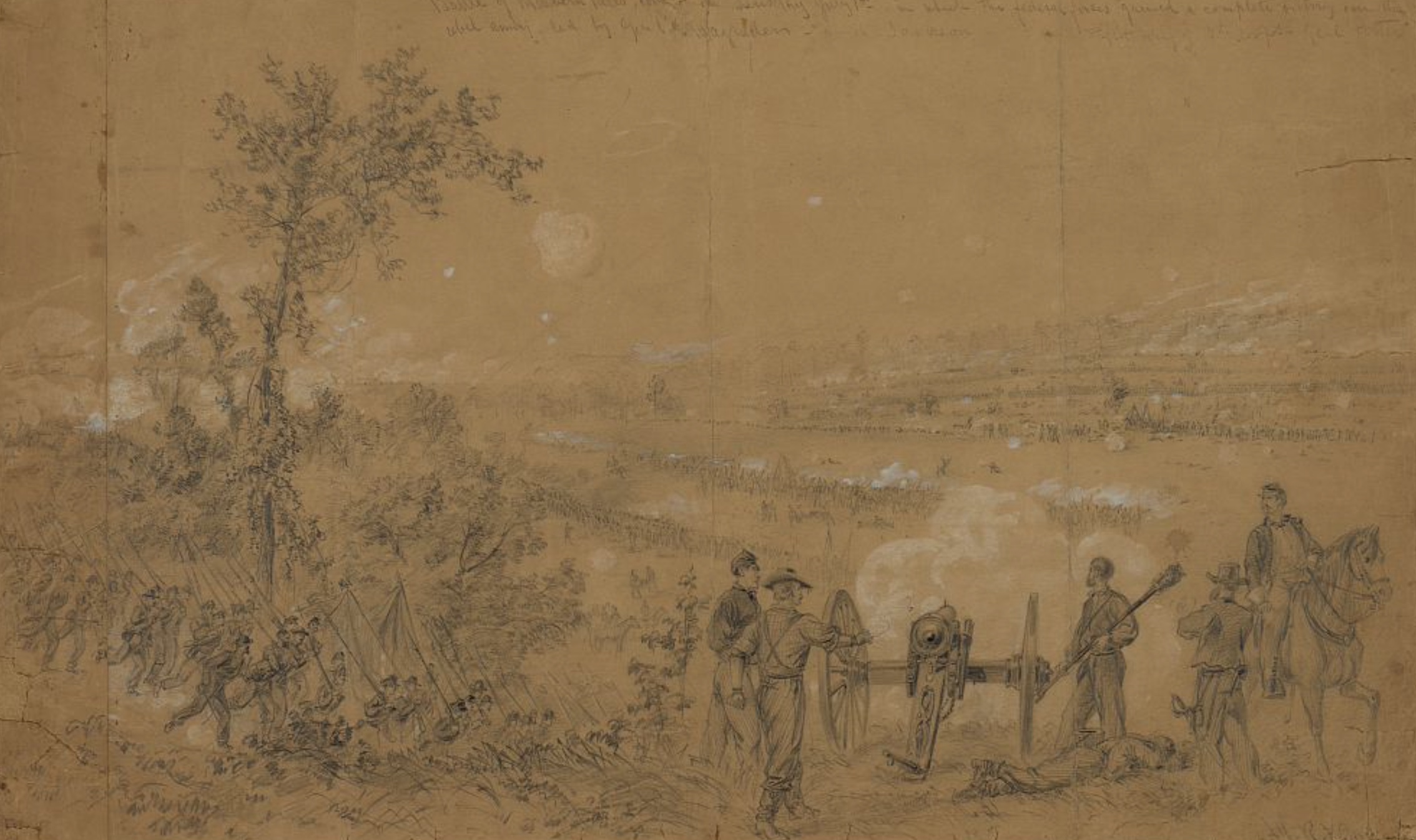

On June 30, Lee ordered Jackson to advance against the Union reardguard at White Oak Swamp. Jackson moved slowly, however, and the resulting attack devolved into an artillery duel with Union forces near White Oak Bridge crossing. Alfred Waud wrote of his sketch (shown here) of the engagement, “These batteries got much injured during the battle—horses and men killed and guns dismounted. The enemy are coming down the distant slope to force the stream[,] troops advancing from the left to meet them.” (Library of Congress)

Two miles to the southwest, a larger Confederate force attacked Union forces at Glendale (depicted above) in hopes of cutting the retreating Army of the Potomac in half. As with previous of the Seven Days Battles, Lee’s plans were poorly executed; the fighting, which produced nearly 8,000 total casualties, proved inconclusive. That night, McClellan wrote of his army, which established a new position on Malvern Hill, “My Army has behaved superbly and have done all that men could do. If none of us escape we shall at least have done honor to the country. I shall do my best to save the Army.” (Library of Congress)

On July 1, the final of the Seven Days Battles took place on Malvern Hill, on which Union forces had establihed a strong position. After an opening exchange of artillery fire, Confederate infantry lanched three charges up the hill, each of them repulsed by Union fire. This sketch of the fighting was made soon after the battle. (Library of Congress)

During the fight for Malvern Hill, Union gunboats on the James River—located only a mile away—lobbed shells into the Confederate ranks. Despite the decisive Union victory at Malvern Hill, Lee had accomplished his overall goal of turning back the Union threat to Richmond. In the North, McClellan’s failure negatively impacted both military and civilian morale. Reflecting on the campaign in a letter to his wife, McClellan wrote, “My conscience is clear at least to this extent—viz.: that I have honestly done the best I could; I shall leave it to others to decide whether that was the best that could have been done—& if they find any who can do better am perfectly willing to step aside & give way.” President Lincoln would remove McClellan from command of the Army of the Potomac before year’s end. (Library of Congress)