When President Jefferson Davis refused to sanction a plot to take the American Civil War to the Great Lakes in the winter of 1863, Confederate Navy Lieutenant Robert D. Minor reluctantly returned to his mundane duties as director of ordnance and hydrography in Richmond.

Still recovering from wounds he received as executive officer of CSS Virginia in the Battle of Hampton Roads, Bob Minor kept studying seizing Michigan, the only Union warship on the Lakes, and turning it loose on targets like the Erie Canal or the copper and iron mines of the Upper Northwest. The “prospects were so inviting and so brilliant,” as inviting and brilliant as they had been two years before when he helped seize the steamer St. Nicholas on the Potomac. He itched for this kind of action.

Sometime in August, James Seddon, secretary of War, and Stephen Mallory, Navy secretary who eagerly embraced the Great Lakes plot drawn up by Navy Lieutenant William Murdaugh, read aloud to Minor part of a letter “containing a proposition for the release of our poor prisoners” on Johnson’s Island in a Lake Erie bay.

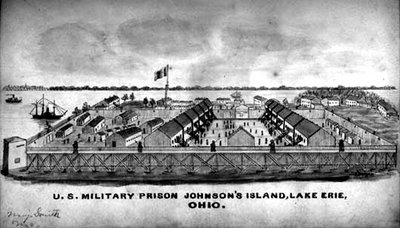

In 1861, the island seemed ideal for a prisoner-of-war camp – well removed from Confederate armies and across miles of water from Canada. So the War Department leased half of the 300-acre island off Sandusky, Ohio, a rail head and small but busy port.

By agreement between the United States and Great Britain, the Great Lakes had been demilitarized for decades. Only the 14-gun steamer Michigan, launched before the War with Mexico, patrolled these waters, usually staying between Buffalo, New York and Erie, Pennsylvania.

But after Gettysburg and Vicksburg, the 45-acre camp became a focus of Confederate war plans. The manpower shortage in Confederate ranks, especially veteran officers, was critical. In the wooden cabins were between 1,500 and 2,000 prisoners – most of them officers. They were men who if given the chance would lead others into battle or fight on as guerrillas behind Northern lines or back in their communities.

Minor was chomping at the bit. With time now a factor before the Great Lakes’ early winter, Mallory told Minor to name the officers who should be in the operation. But on the point of command, Minor demurred, saying that John Wilkinson had rank and proven success as a blockade runner. Another Virginian like Minor and a former prisoner of war, he had been summoned from Wilmington by Seddon to hear about the operation.

Davis now reluctantly gave his approval to liberate the prisoners with the proviso that British neutrality be preserved. Wilkinson marveled, “How this was to be avoided has ever seemed impossible to me.”

The senior officers were Wilkinson, Minor, and B.P. Loyall, another Virginian and commandant of the Confederate States Naval Academy. They commanded a crew of officers and noncommissioned officers of 22 or 26 (accounts differ). The crew only knew they were on a “special mission,” not where they were going or what they were to do.

It was already October as they fitted out blockade runner R.E. Lee and loaded it with cotton. The cotton was to be sold in Halifax with proceeds to buy “blankets, shoes, etc. for the army” and the rest plus the gold Wilkinson carried was “for the benefit of the prisoners, if released.”

The night of October 10 in Wilmington was disturbingly clear, but Wilkinson decided to run at full speed for an hour. He deviated from the usual course to gain time. The first shot from an inshore blockader fell short, but the second ricocheted off the water and over the fleeing R.E. Lee. The third found its mark, passing through a bulwark and setting a bale ablaze. With flames leaping high into the air, the crew wrestled the bale overboard. As the blockade runner raced past Frying Pan Shoals, the cruiser fired several more rounds, but they missed widely.

To the curious and potential cotton brokers and the Union agents sniffing around Halifax’s port, Wilkinson spread word that the ship would soon be on its way to Britain.

Keeping the real mission secret proved crucial. A crewman named Leggett whom the three senior officers didn’t know demanded a month’s wages when they made port and then deserted; Wilkinson believed him a traitor and a spy. But in keeping with Wilkinson’s story, Lee under a new commander again put to sea, and Leggett didn’t know enough to stymie the raiders.

The Confederates ashore split into groups, taking different routes to Montreal “where we all met under assumed names” about two weeks after leaving North Carolina.

The first task there was to find “friends” like George Proctor Kane, the former police marshal of Baltimore, who were expecting them. Kane had been arrested for his Confederate sympathies and confined with Wilkinson in Fort Warren in Boston Harbor.

The raiders now had to let the prisoners know that a rescue attempt was in train. Again, the “friends” and “friends of friends” come into play, letting two imprisoned generals how to communicate with the raiders through the personal columns of the New York Herald. Wilkinson took out the ad saying that a few nights after November 4, “a carriage would be at the door, when all seeming obstacles would be removed.” The obstacles were Michigan and the guards.

Wilkinson next learned from an escaped prisoner what the conditions were on the island and in Sandusky. As helpful as this was, the daily reports coming from a retired British army officer posing as a duck hunter in Sandusky using a “pre-arranged vocabulary” were tantalizing.

Michigan was anchored about 200 yards off shore in the bay with its guns trained on the island giving any attacker coming off the lake an advantage. In addition, the camp itself was not heavily defended – about 400 soldiers were assigned there with only a single howitzer with them.

As Minor described the revised plan, the men were to leave Montreal for Windsor, Ontario. There, augmented by 180 escaped Confederates, they were to board a civilian steamer and “play the old St. Nicholas game.” On the island, the prisoners were to overpower their guards and be ready to board the captured steamer that would return all to the safety of Canada.

A Canadian named McQuaig, described “as a good and reliable Southern sympathizer,” said the idea was flawed. Speaking as the manager of a line of steamers, he said few vessels called at Windsor and stops along the Canadian shore were intermittent.

As plans were changed, the raiders set about arming themselves. Two 9-pounders were “quietly purchased,” along with dumb-bells “substituted for cannon balls” to avoid suspicion. Likewise they substituted butcher knives for cutlasses. They also bought one-hundred Navy Colts and ammunition, slugs, bullets, and powder, and grapnels for the boarding. But when the time came to step forward, only thirty-two men said they were in.

With so few available, the plan was revised yet again. This time, one of the new volunteers was dispatched to New York to buy a ticket for a group of men who would be disguised as laborers boarding a steamer from Ogdensburg, New York, bound for Chicago. The men would come on at St. Catherine’s on the Welland Canal. Another man with casks and boxes marked “Machinery, Chicago,” but loaded with the arms and ammunition would come on there as well but keep his distance from the others.

When out of British jurisdiction, they would overpower the civilian crew. At first light, the steamer under Confederate control to collide with Michigan “and carry her by cutlass and pistol, and then with her guns loaded with grape and canister, trained on prison headquarters, send a boat on shore to demand an unconditional surrender” and the release of the prisoners.

Minor fully expected the camp commander Major W.S. Pierson, “a humane man,” to comply rather than see any bloodshed.

As to how the Confederates would bring the 1,500 to 2,000 prisoners to Canada, the plan then called for an attack on Sandusky to take command of steamers there.

What thrilled Minor the most was the idea that with the taking of Michigan, “we would have had the lake shore from Sandusky to Buffalo at our mercy, with all the vast commerce of Lake Erie as our just and lawful prey.” It was a revised Murdaugh plan and what was to have happened to Washington, Georgetown, and Baltimore after St. Nicholas was captured.

Now waiting at St. Catherine’s, the raiders learned Lord Monck, the governor general, had alerted Lord Lyons, the British minister in Washington, about the plot. Once notified, Secretary of War Edward Stanton put the Great Lakes’ governors and military authorities on high alert. The would-be duck hunting British officer hurried back to Canada with a firsthand account of how the strengthened camp’s garrison and the sloop’s crew were expecting them.

Minor was fit to be tied, especially when he learned that McQuaig was the one who betrayed them to a provincial legislator. The naval officer could only speculate on his motives – “failure, exile, loss of position and imprisonment” – for his turnabout.

The only thing the Confederates could do was go their different ways. No longer using disguises, Minor, Wilkinson, and Loyall lingered for about a week in Montreal giving the Canadians “every opportunity to arrest us,” but Monck apparently didn’t want to “complicate the matter or to show his zeal for the Yankees.” What had begun with a bold idea from a naval officer looking for action that winter was ending with a few men “in open wagons and buggies” making their way eastward into New Brunswick and cursing their luck in late November.

The Confederate government, however, was not through with Johnson’s Island’s “prizes” – the prisoners still held there. It was desperate for seasoned soldiers. Looking at those later failed attempts, Murdaugh wrote bitterly, “This is a specimen of how the Navy was treated and how it was managed” by Davis.

John Grady, a former managing editor of Navy Times and retired communications director of the Association of the United States Army, is completing a biography on Matthew Fontaine Maury. He has contributed to the New York Times “Disunion” series, the Civil War Monitor, and is a blogger for the Navy’s Sesquicentennial of the Civil War site.

Sources: Robert D. Minor to Franklin Buchanan, February 2, 1864, Official Records of the War of the Rebellion Navy, Ser. 1, Vol. 2, pp. 822-828; Lieutenant Murdaugh to Secretary Mallory, February 7, 1863, ORN, Ser. 1, Vol. 2, pp. 828-830; Colonial Williamsburg Shirley Plantation Collection Guide; Library of Virginia Guide to Confederate Navy Records; The Papers of Jefferson Davis, Louisiana State University, 1999, Vol. 9 p. 243, Vol. 10, p. 86; William Harwar Parker, Recollections of a Naval Officer, 1841-1865; John Wilkinson, Narrative of a Blockade Runner.