On July 18, 1863, Union troops commanded by Brigadier General Quincy Gillmore launched an attack on Fort Wagner, the Confederate bastion that protected Morris Island, located south of Charleston Harbor—part of the larger Federal attempt to capture the city of Charleston. While the assault failed, the men of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, the African-American regiment commanded by Colonel Robert Gould Shaw that led the Union advance, were subsequently praised for their valor—a significant step on the path toward the acceptance of black troops among northern soldiers and civilians. Below are images and illustrations that help tell the story of the noteworthy engagement.

Robert Gould Shaw, 25, was the colonel of the 54th Massachusetts, a unit formed in the spring of 1863. The son of prominent Boston abolitionists, Shaw had previously served as an officer in the 2nd Massachusetts Infantry, in which he saw action at the First Battle of Winchester, the Battle of Cedar Creek, and the Battle of Antietam, where he was wounded. Shown here: Shaw as a lieutenant in the 2nd Massachusetts (left) and as colonel of the 54th Massachusetts. (Both courtesy of the Library of Congress.)

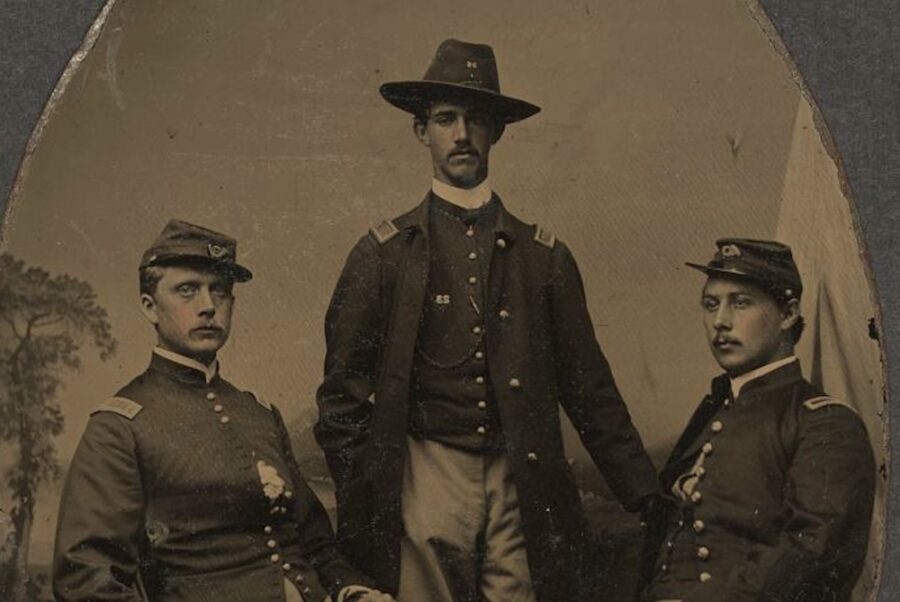

While the 54th Massachusetts’ enlisted men were African Americans, the regiment’s officers were white. Many of them, like Shaw, were from abolitionist families. Shown here (from left to right) are Second Lieutenant Ezekiel Gaulbert Tomlinson, Captain Luis F. Emilio, and Second Lieutenant Daniel G. Spear. (Library of Congress)

Boston’s free black community, along with a number of prominent black and white abolitionists, featured prominently in recruiting men for the regiment. (Frederick Douglass’ two sons were among the first to enlist.) Shown here are Alexander H. Johnson (left), a musician from Company C, and Private John Gooseberry, one of 21 men from Canada who enlisted in the 54th. (Both Massachusetts Historical Society)

Sergeant Henry Steward (above, left) joined the regiment in April 1863 and was active in recruiting additonal men. Private Abraham Brown (above, right) served in Company E. (Both Massachusetts Historical Society)

At dusk on July 18, 1863, the Shaw and the 54th led the Union attack on Fort Wagner. When the men were about 150 yards from the fort, its Confederate defenders opened fire with artillery and small arms. Shown here is a depiction of the assault published in Harper’s Weekly.

Despite taking heavy fire from the fort, the 54th Massachusetts was able to reach the parapet, as shown in this depiction of the battle by Thomas Nast. (USAHEC)

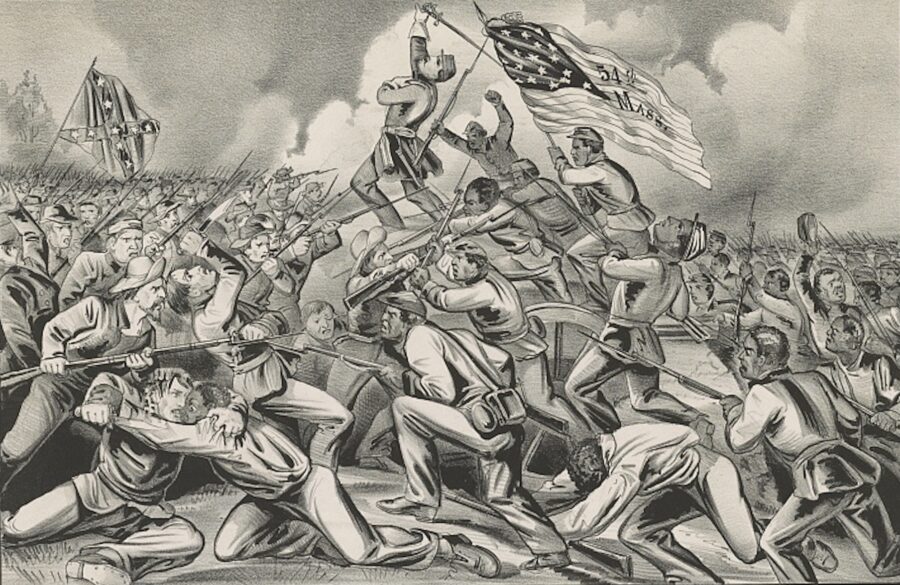

After a fierce hand-to-hand struggle—and the death of Colonel Shaw, who was shot in the chest multiple times after climbing the parapet—the 54th was forced back. This illustration by Currier & Ives, published in 1863, depicts the ferocity of the struggle. (Library of Congress)

After the 54th pulled back, multiple white Union regiments tried and failed to take the fort. By the time the fighting was over, the attacking Union force had suffered some 1,500 casualties. The 54th, which numbered approximately 600 men going into the fight, had 270 of its men killed, wounded, or captured. Shown here: Kurz & Allison’s “Storming of Fort Wagner.” (Library of Congress)

For the next two months, Union guns hammered the fort. In early September, the Confederates abaondoned Wagner to Union forces, a moment marked in this sketch by Alfred Waud. (Library of Congress)

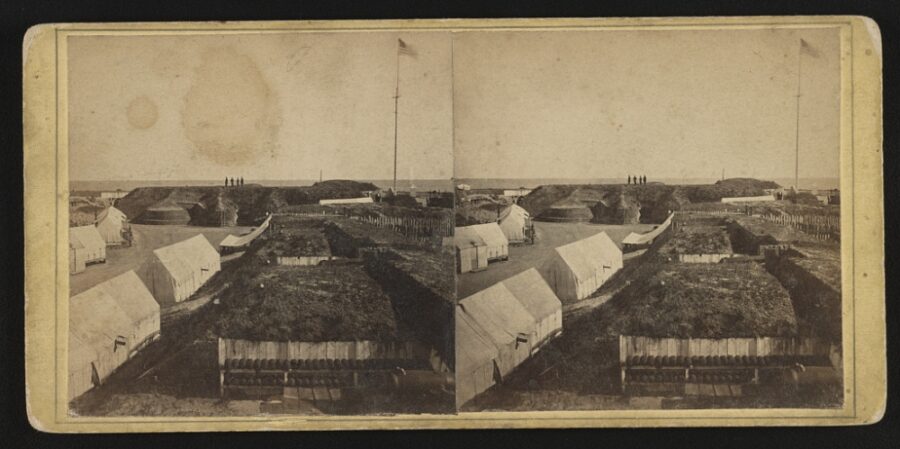

This stereoview shows the interior of Fort Wagner after its capture by Union forces. (Library of Congress)

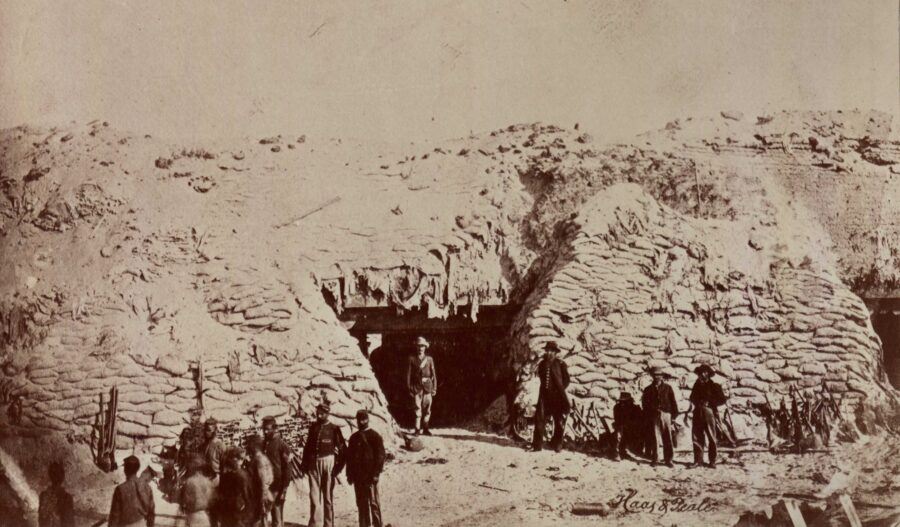

Union troops—including some from the 54th Massachusettes—tour the inside of Fort Wagner after Union forces captured it. (USAHEC)

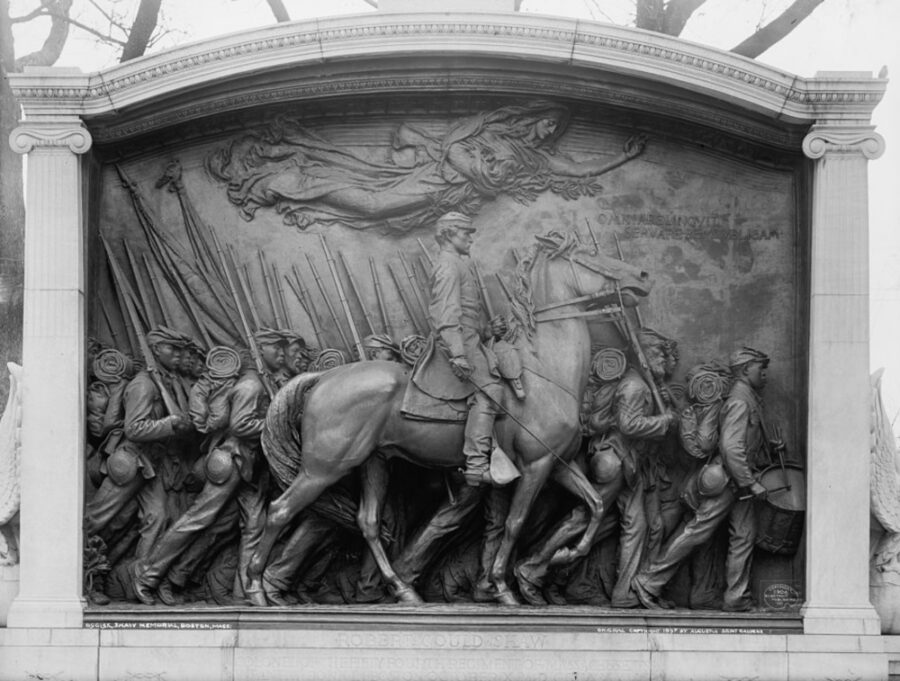

The 54th Massachusetts’ performance in battle at Fort Wagner garnered praise throughout the North—and helped encourage the further enlistment of African-American troops. In the late 1800s, Augustus Saint-Gaudens constructed a monument to Shaw and the regiment on the Boston Common. It’s shown here as it appeared in the early 20th century. (Library of Congress)