Quantrill at Lawrence: The Untold Story by Paul Petersen. Pelican Publishing, 2011. Cloth, ISBN: 1589809092. $26.95.

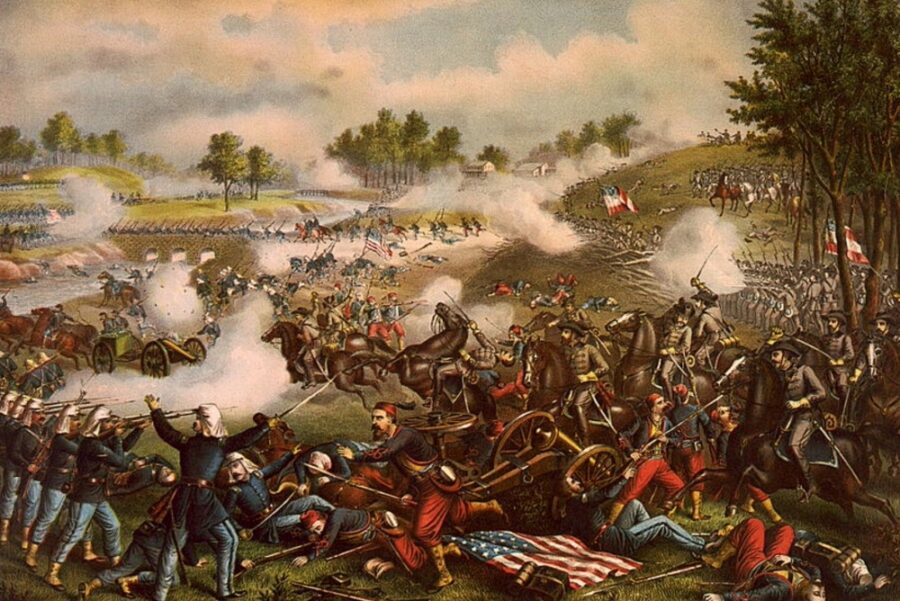

Quantrill at Lawrence: The Untold Story is a well-written and provocative book that ultimately falls short of its goal. William Clarke Quantrill’s infamous raid on Lawrence, Kansas, in August 1863, remains an important symbol of the Civil War in the Border States and continues to be used as an example of the atrocities of guerrilla warfare. According to traditional interpretations, the Lawrence raid marked the Missouri Confederates as treacherous thieves and killers, men who murdered in cold blood, driven by their racist hatred of blacks and abolitionists. In this military history, Paul R. Petersen sets out to overturn that traditional view, arguing that, far from being a heinous act, the attack on Lawrence should be “considered one of the most daring light cavalry raids of the war” (9). He contends that the Lawrence raid was a response to the “most heinous and barbaric act committed by either side during the Civil War,” and that “no other leader but Quantrill could have possibly carried off the raid successfully” (9-10).

Quantrill at Lawrence: The Untold Story is a well-written and provocative book that ultimately falls short of its goal. William Clarke Quantrill’s infamous raid on Lawrence, Kansas, in August 1863, remains an important symbol of the Civil War in the Border States and continues to be used as an example of the atrocities of guerrilla warfare. According to traditional interpretations, the Lawrence raid marked the Missouri Confederates as treacherous thieves and killers, men who murdered in cold blood, driven by their racist hatred of blacks and abolitionists. In this military history, Paul R. Petersen sets out to overturn that traditional view, arguing that, far from being a heinous act, the attack on Lawrence should be “considered one of the most daring light cavalry raids of the war” (9). He contends that the Lawrence raid was a response to the “most heinous and barbaric act committed by either side during the Civil War,” and that “no other leader but Quantrill could have possibly carried off the raid successfully” (9-10).

Petersen correctly argues that the Lawrence raid must be understood in the context of the border wars in Kansas and Missouri and that it was in retaliation to the “premeditated murder by Kansas Jayhawkers of five young Southern girls who were close relatives of members of . . . Quantrill’s partisan ranger company.” Arrested for spying because of their support for their male relatives fighting against the Union, the women were among others imprisoned in a Kansas City hotel by order of General Thomas Ewing. The building collapsed and the five women died. Petersen insists that the building was “undermined by solders of the Ninth Kansas Jayhawker Regiment” who cut the supporting structure of the hotel and caused it to collapse (22). Other historians have noted that the hotel had failed an inspection which found that it had structural problems, but most have seen this as negligence (perhaps criminal) rather than outright murder. Petersen’s citation points to a secondary source published in 1928 and he does not offer primary evidence to support this controversial argument. Whether or not the hotel collapse was actually murder, Petersen is correct in arguing that it spurred Quantrill’s raid. Bushwhackers (the pro-slavery guerrillas) certainly sought revenge for the death of their womenfolk and Lawrence, Kansas, long a symbol of abolitionism and Free-State politics, served as the perfect target for their vengeance.

An important part of this book is the author’s examination of the individuals involved in the raid. Although biased against the Jayhawkers (the advocates of abolitionism and Union in Kansas) and in favor of Quantrill and his men, Petersen offers insightful biographical background on a wide range of people connected to the Lawrence attack. Political and military leaders stand alongside little-known soldiers and citizens on both sides of the conflict. This allows Peterson to show the bitterness of the border wars, setting up the context of the raid in a personal way, as the reader learns about the history of the conflict throughout the 1850s and the first years of the Civil War through the lens of biography. Here, however, his bias gets in the way, as he consistently paints Jayhawkers as villains and excuses bushwhackers as good soldiers seeking justice. At times, he manages to overcome this problem, but not enough to take advantage of the opportunity to show that both sides were guilty of atrocities and that both sides claimed to hold the moral high ground. Instead, he whitewashes the bushwhackers and maligns the Jayhawkers. Despite this, Petersen does punch holes in the myth of an innocent Lawrence by rightly pointing out the corruption and mixed motives on the Unionist side. The issues he raises could have been even more significant if he had expanded further on the symbolism of Lawrence for both sides, both during the conflict and after the Civil War. Indeed, his whole argument would have benefitted from a closer study of the role of historical memory to reveal how historians and other chroniclers constructed the myth of the Lawrence raid.[i]

His bias also leads Petersen to claim that the Lawrence raid was justified not only because Quantrill and his men thought that the Jayhawkers had murdered their women, but also by the fact that the Unionists were stealing southern property. This included a wide variety of household goods, food, and other materials taken in raids into Missouri. And it included slaves, as the bushwhackers considered those individuals freed by the abolitionists to be stolen property. While he is correct in pointing out that this is the way that Quantrill and his men saw the situation, Petersen ignores the moral issues involved on the other side in favor of sympathizing with the southern guerrillas (164-175). Throughout the book, he refers to African Americans as “Negroes,” a now-outdated usage that will offend many scholars.

Because of his obvious bias, most academic historians and many readers will dismiss Petersen as a neo-Confederate and refuse to go further. That is unfortunate, because he makes many important points in his tactical-level study of the military action. Those who are willing to read on despite the author’s bias will find a gripping account of the infamous raid. Petersen writes well, with the dramatic style of a novelist. He takes the reader along for the ride in a vivid and insightful account that is literally street-level. Here the biographical backgrounds come together, as the individuals introduced earlier interact in the chaotic events of the raid. Petersen’s bias weakens his case and many will disagree with his conclusion that the Lawrence attack should be seen as a legitimate and successful cavalry raid. But readers will appreciate his storytelling and historians should give the contentions he makes in telling his untold story further consideration.

James Fuller is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Indianapolis.

[i]Especially useful on these matters of memory is Nicole Etcheson, Bleeding Kansas: Contested Liberty in the Civil War Era (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2004).