A Civil War greenback

In the Voices section of the Spring 2020 issue of The Civil War Monitor we highlighted quotes by Union and Confederate soldiers about the excitement that often accompanied payday in camp. Unfortunately, we didn’t have room to include all that we found. Below are those that didn’t make the cut.

“The noises and rows, which always accompany pay-day, have subsided to a sufficient extent to permit me to take off my sabre and pistol, with which I have been prowling through the company street, ‘a terror to evil-doers’….”

—Lieutenant William Wheeler, 13th New York Light Artillery, in a letter home, January 28, 1862

“The paymaster came on Saturday with his $7 per month. Not half the men would sign the rolls or take their pay, and those who did, did so under protest. It is too bad. Seven dollars a month for the heroes of Olustee!”

—Lieutenant Oliver Wilcox Norton, 8th U.S. Colored Troops, in a letter to his sister, May 10, 1864. Until the following month, when Congress granted equal pay to all Union troops, black soldiers received $10 a month, $3 of which were automatically deducted for clothing, as opposed to white soldiers’ wages of $13 a month, with no deduction for clothing.

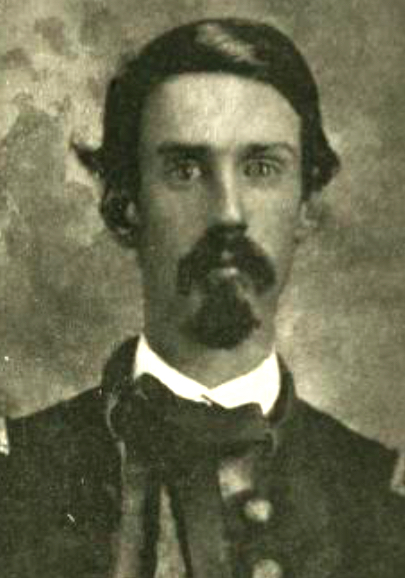

Lieutenant William Thompson Lusk, 79th New York Infantry

“We are now going through a stage dreaded by all officers in the army, viz: that immediately following upon pay-day. Notwithstanding the utmost precautions the men contrive to obtain liquor, and when intoxicated are well-nigh uncontrollable, so that the utmost vigilance is needful. As the number of our officers is but small we are kept almost constantly active. When the money is once spent we will then breathe more freely.”

—Lieutenant William Thompson Lusk, 79th New York Infantry, in a letter to his mother, August 11, 1861

“The regiment was mustered for pay during the morning, after which the men signed the rolls. Pay day is always an event in the army, almost every man being dead broke long before the paymaster comes around. The men, generally speaking, are improvident, and some of them great gamblers, soon getting rid of their cash; many send home a large proportion of their pay to their families, and the express companies do a big business in money packages every pay day; we are all paid in paper money, and sometimes with coupon, interest-bearing notes; my pay amounts to about one hundred and sixty dollars per month, a third of which I send home for safekeeping, the balance I spend.”

—Josiah Favill, 57th New York Infantry, in his diary, August 1862

“The day was bright and cool, — the regiment moved off at twelve o’clock. Hard bread in haversacks, and hoping for something better. Money in pocket, and, I am sorry to say, an occasional excess of whiskey in a guilty canteen. Pay-day has its evils, as I thought when directing two drunken men to be tied and put in a wagon.”

—Major Wilder Dwight, 2nd Massachusetts Infantry, in a letter home, August 23, 1861

“The government owes me $200.00 and if pay day ever comes I will send you quite a sum. I don’t need it here.”

—Chauncey Herbert Cooke, 25th Wisconsin Infantry, in a letter to his father, July 31, 1864

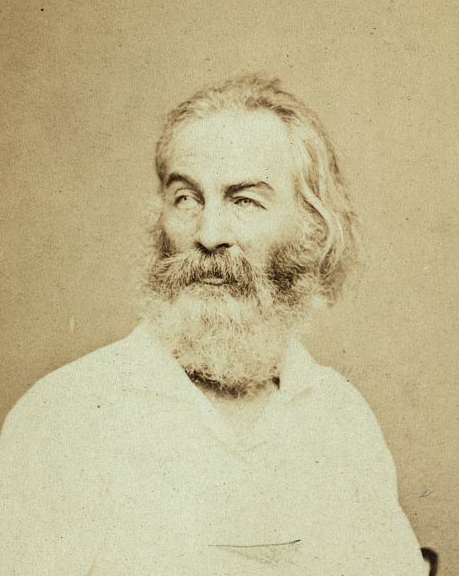

Walt Whitman

“The poor soldiers are continually coming in from the hospitals, etc., to get their pay—some of them waiting for it to go home. They climb up here, quite exhausted, and then find it is no good, for there is no money to pay them; there are two or three paymasters’ desks in this room, and the scenes of disappointment are quite affecting. Here they wait in Washington, perhaps week after week, wretched and heart-sick—this is the greatest place of delays and puttings off, and no finding the clue to anything.”

—Poet Walt Whitman, who worked in the army’s paymaster’s office in Washington, D.C., in a letter to his sister-in-law, January 2, 1863

“The rumor now runs that the paymaster will be at hand tomorrow, but he is about as reliable as Johnston, for we have been something like a week looking for both these gentlemen. I confess I would rather meet greenbacks than graybacks.”

—Osborn H. Oldroyd, 20th Ohio Infantry, in a reference to Confederate general Joseph E. Johnston during the campaign for Vicksburg, Mississippi, in his diary, July 2, 1863

“[T]he Government paymaster arrived, the first paymaster we had seen for a long time, and our regiment was paid. Soldiers look with considerable interest for the army paymaster. The pay the soldiers receive, small as it is, … is to them quite an important matter. A little money to buy things not furnished by the Government, is at times much needed. Again, many of the soldiers have at home aged parents, a widowed mother, young sisters, or perhaps a wife and infant children to whom the small pittance of five or ten dollars a month is a matter of great importance. These things make the paymaster’s visits of much interest to the soldiers. Of course there are sure to be some who put their money to such bad use that it would be better for them not to have any. This class of people will be found everywhere. Their number, however, is small with us.”

—Albert O’Connell Marshall, 33rd Illinois Infantry, in his memoirs

“A very pleasant morning…. Believe the enemy must be in this vicinity in a strong force…. Later a surprise came when orders came to fall in for pay, the Paymaster having shown up in our camp. Too much money for a fellow to carry while in front of the enemy. The Confeds liked to get hold of greenbacks.”

—Charles H. Lynch, 18th Connecticut Infantry, in his diary, September 2, 1864

“Tell Benjamin that if he expects a harvest he must put in the seed. Take good care of what he puts in and to do it in season. Tell him that Mother Earth is the best paymaster there is. She always pays her fruits in their season, while the paymasters of the United States pay when they get the money. We have not been paid yet. Tell him therefore to plant and sow plentifully and he will be sure of his pay.”

—Captain Jonathan H. Johnson, 15th New Hampshire Infantry, with advice for a family member in a letter home, April 12, 1863

“Since my last we have been visited by the paymaster. How it happens that nine months regiments, and bounty regiments at that, are paid off, while old regiments, which have not seen the paymaster for six or nine months, are skipped, passeth the understanding of even the favored ones like ourselves. It is a circumstance certainly not calculated to improve the relations between the old and new regiments, none the best at present.”

—Zenas T. Haines, 44th Massachusetts Infantry, a nine-month regiment, in a letter home, January 18, 1863

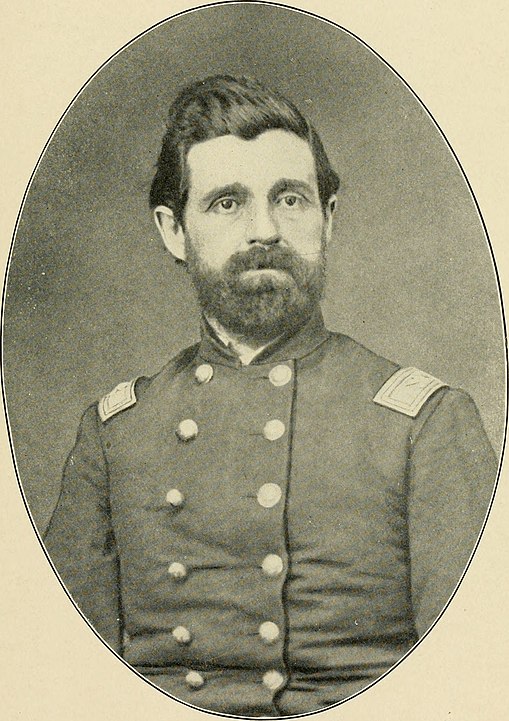

Colonel William Penn Lyon, 13th Wisconsin Infantry

“We had quite an excitement last night. I awoke with the feeling that there was some one in the tent, and I raised up and saw a man on his hands and knees looking up at me. I screamed, ‘William, there is a man in the tent.’ I awoke all the inmates of all the tents around us with the scream. The man was looking for William’s trousers, I suppose, and found garments he did not expect to see. He got out very quickly.”

—Adelia Lyon, wife of Colonel William Penn Lyon, on an incident involving a thief in the camp of the 13th Wisconsin Infantry, where she was visiting, the day after the paymaster had come, in her diary, June 10, 1865

“The monotony of camp life was at length relieved by the appearance … of our paymaster with his treasure chest, and visions of bright new greenbacks and the consequent supplies of sutler’s stores, etc., cheered us greatly. The happy, smiling faces that gathered around the sergeant’s tent for the signing of the ‘pay rolls’ became suddenly clouded when it was announced that although six months’ pay was due us, we were to receive but four.”

—George H. Allen, 4th Rhode Island Infantry, on a visit by the paymaster to his regiment’s camp in January 1863, in his memoirs

“[A] thousand pairs of eyes anxiously watched the road for the approach of the man who carried the panacea for all ills.”

—A soldier in the 109th Illinois Infantry, on the state of the men after word arrived that the paymaster would soon arrive in camp, in a letter to his hometown newspaper, September 1862

“Paymaster arrived; he to whom we all bow with obsequious respect. A paymaster’s arrival will produce more joy in camp than is said to have been produced in heaven over the one sinner that repenteth.”

—Charles E. Davis, 13th Massachusetts Infantry, in his postwar history of his regiment