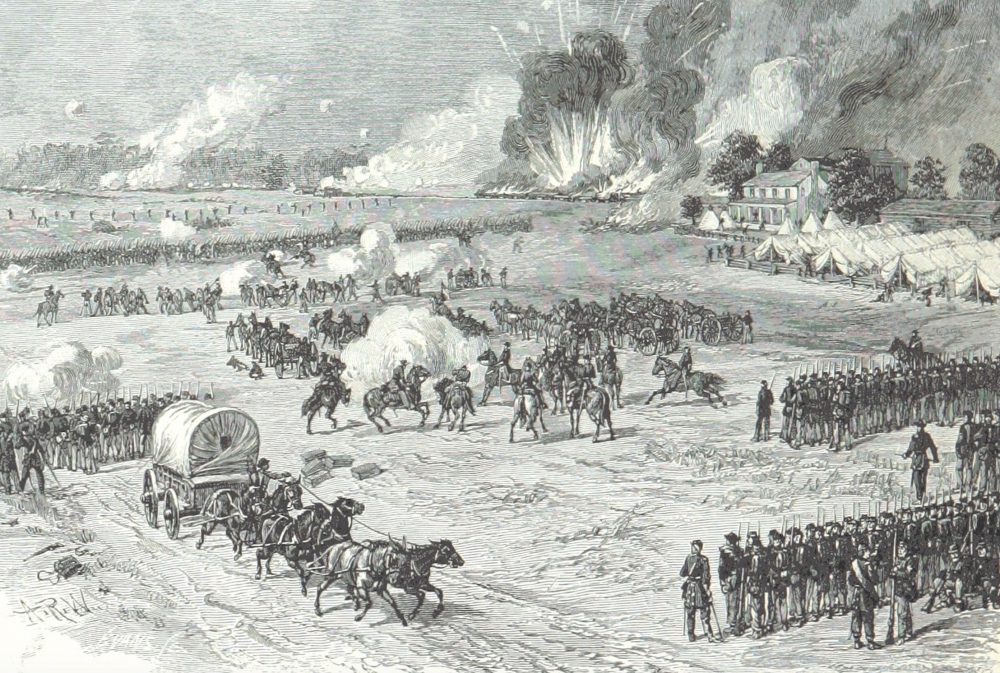

George McClellan’s Army of the Potomac on the move during the Peninsula Campaign

In the spring and early summer of 1862, Union general George B. McClellan’s attempt to capture the Confederate capital by advancing up the Virginia Peninsula involved the largest amphibious operation of the war, saw perhaps Robert E. Lee’s best chance to destroy the Army of the Potomac, and included frontal assaults that dwarfed the size of Pickett’s Charge. Its results led to President Lincoln’s decision to use emancipation as a means of saving the Union, and thus the event merits as much attention, if not more, than such battles as Shiloh, Antietam, and Gettysburg. While writers have relatively neglected the Peninsula Campaign, there are several essential works that provide solid analysis of the event.

The classics are the best place to begin, and luckily two of the most colorful “old school” Civil War historians tackled the Peninsula Campaign. Clifford Dowdey, in The Seven Days: The Emergence of Lee(1964), uses a conversational style to provide a good overview of McClellan’s bold maneuver. However, Dowdey mainly focuses on Lee’s command of the Army of Northern Virginia after Joseph E. Johnston was wounded in battle at Seven Pines. Dowdey is unafraid to deliver sharp judgments of both Union and Confederate commanders and is particularly critical of Johnston and John Magruder (describing the former as a “dandified little general” who was a “lazy, hazy thinker” with battle plans that were “deranged”). Dowdey’s familiarity with the terrain and the often-confusing roads over which the armies fought is a particular strength of the work. The book casts Lee as its hero, and makes the case that the campaign’s largest impact was his rise as a commander whose future successes would allow the Confederacy to fight on for three bloody years.

A similar take can be found in the first volume of Douglas Southall Freeman’s classic Lee’s Lieutenants, A Study in Command(1942). Freeman needs no introduction to students of the Civil War. Along with the works of Bruce Catton and Shelby Foote, the Richmond journalist’s writings are among the most readable of all Civil War histories. In Lee’s Lieutenants, Freeman provides an elegantly written narrative of the campaign. His focus is the leadership of the Army of Northern Virginia, and thus his work’s most interesting interpretive points involve Lee’s struggle to weed out ineffective commanders and to weld together an efficient staff.

In 1992, Stephen W. Sears provided the first truly comprehensive narrative of the operation with To the Gates of Richmond: The Peninsula Campaign, which remains the single best work on the subject. He examines the campaign from both the Union and Confederate perspectives, provides more than just an evaluation of Lee’s emergence, and deals objectively with the performances of Magruder and Johnston. Sears also offers a well-supported analysis of McClellan, showing him as politically at odds with the Lincoln administration, delusional in his overestimation of the number of Confederate troops he faced, and possessing a bizarre skill for being absent from the battlefield during combat. Yet the work’s greatest strength is that Sears does not focus exclusively on leadership. He turns his lens on the rank and file, skillfully integrating their diaries, letters, and memoirs.

Union soldiers advance during the Battle of Savage’s Station during the Peninsula Campaign.

All Civil War enthusiasts should delve into such extant primary sources, and fortunately a wealth of them exist that deal with the Peninsula Campaign. One of the best is Katharine Prescott Wormeley’s The Other Side of War: With the Army of the Potomac, a collection of the nurse’s letters written from the Virginia Peninsula. Published in 1888 (and full text now available online at Google Books), Wormeley’s letters provide an engaging account of her transformation from a young, pampered New England woman to a hardened war nurse. Her writings illuminate the journey that many women took as the conflict challenged and altered Victorian gender roles. Most compelling, they graphically strip away the romanticized image of war with which her generation went into the conflict, and which too often clouds our impressions today. Wormeley maintains that no one can understand war without witnessing the horror of thousands of suffering soldiers. “It is a piteous site to see,” she observed. “We may all sentimentalize over [war’s] possibilities when we see regiments go off [to fight], or when we hear of battle, but it is … far from the reality.” Worse still were “the screams of the men. It is when I think of it afterwards that it is so dreadful.”

Relying more on secondary than primary sources, Kevin Dougherty and J. Michael Moore’s The Peninsula Campaign of 1862: A Military Analysis(2005) nevertheless offers a fascinating approach to the campaign. Less a history lesson than a military analysis, this concise, tightly focused work uses several historians’ interpretations to cogently analyze the campaign’s most important strategic questions. Its most intriguing contributions are its emphasis of McClellan’s failures to coordinate his efforts with the Union navy (compared to Ulysses S. Grant’s successful joint army-navy operation against Fort Henry a few months earlier) and how it introduces modern concepts of military terrain analysis. In doing so, the authors demonstrate that today’s military officers could learn much from the Peninsula Campaign.

But while the campaign’s military questions have received solid treatment, few works have effectively revealed the event’s larger importance. One exception is The Richmond Campaign of 1862: The Peninsula & the Seven Days(2000), a collection of essays by notable historians, edited by Gary Gallagher. Some contributors consider the typical military questions surrounding the campaign (such as Magruder’s ineptitude, McClellan’s failures, and the strangely ineffective performance of Stonewall Jackson), while essays by Gallagher, James Marten, and William A. Blair provide a broader social and political context to the fighting. The authors demonstrate the campaign’s impact on the direction of the war, the southern loyalty of both black and white Virginians, and the growing political influence of those northerners who pushed for more radical means for saving the Union, including emancipation.

There are other fine studies of the Peninsula Campaign (especially in regards to the Seven Days Battles), but collectively these six provide highly readable narratives, dig deep into its military questions, and scratch the surface of its broader implications and meanings. Hopefully they will entice other historians to further examine the campaign’s social and political aspects, giving it the attention that it deserves as one of the war’s major events.

Glenn David Brasher is an instructor of history at the University of Alabama and the author of The Peninsula Campaign and the Necessity of Emancipation: African Americans & the Fight for Freedom(2012).

This article appeared in the Spring 2012 issue (Vol. 2, No. 2) of The Civil War Monitor.