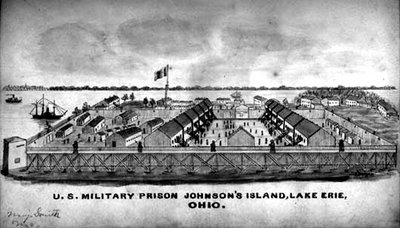

A prison register was a seemingly strange place to write the Our Father. Nonetheless, one guard from the 128th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, charged with guarding Johnson’s Island Prison, scribbled the Lord’s Prayer on the first page of the 1864 logbook. Many things may have been running through his mind when he picked up the ledger to begin chronicling the offenses and punishments of inmates. Perhaps he was longing for the war to be over. Maybe he was praying for forgiveness for those in his charge. Or maybe he prayed that he would not be tempted to commit an offense that would cause another guard to record his name in the book. After all, the majority of names of the men inscribed in the ledger belonged to this anonymous guard’s regiment. Many members of the 128th Ohio, also known as Hoffman’s Battalion, had no prior military experience, and few among them probably craved such an opportunity. An assignment to guard duty at Johnson’s Island, while monotonous, likely spared most garrison members from serving at the battlefront. The unglamorous task of guarding Confederate prisoners, however, tempted many members of the 128th Ohio to commit crimes that resulted in punishments that either closely resembled or exactly mirrored those used to correct the offenses of penitentiary inmates. Paging through this prison register from Johnsons Island reveals that many members of the 128th were charged with both military and common crimes ranging from absence without leave, drunkenness while on duty, neglect of duty, desertion, horse stealing, and robbery. Union authorities consequently punished them with periods of hard labor of up to 90 days, hard labor with ball and chain, close confinement in the dungeon on a bread and water diet, forfeiture of pay, and close confinement in a cell wearing irons.1

Such punishments were not limited to Johnsons Island. Union and Confederate authorities also employed these same disciplinary measures commonly used at penitentiaries at military prisons such as Camp Chase, Old Capitol Prison, Castle Thunder, Salisbury, and even Andersonville. Inmates were aware that one misstep could lead to even greater humiliation and constriction of personal freedom. Camp Chase inmate John King, for example, recalled that escape attempts gone awry would lead to the offender being suspended by the thumbs to the point of insanity, wearing a ball and chain while performing hard labor, or being bucked and gagged for hours in a solitary cell. On some levels, this is not surprising since nineteenth-century penitentiary discipline was modeled after military practice – guards marched inmates to and fro in lock step, compelled them to work, administered whippings and/or bucking and gagging for bad behavior, and sentenced troublemakers to solitary confinement on reduced rations. Civil War military prisons, their administration, and their practices of punishment emerged out of necessity during the same century that incarceration as punishment developed formally, inspiring military prison administrators to employ punitive techniques commonly used throughout the century to punish both common criminals and prisoners of war.2

Even though Union and Confederate administrators and prisoners of war themselves tried to draw a distinction between common criminals and enemy combatants, the magnitude of the prisoner crisis made this a difficult, if not impossible, task. The 1863 Lieber Code may have actually added some confusion to the situation as it determined that while prisoners of war were not considered criminal, they could be compelled to work for their captors’ government. The U.S. Congress reinforced this notion the next year, determining that prisoners of wary may be “employed on the public works,” as penitentiary inmates often were since the early part of the century. Sometimes officials like Union Commissary General William Hoffman, ordered subordinates to be conscious of the differences in treatment that each type of inmate was assumed to deserve. For example, on September 3, 1864, Hoffman issued a circular, directing officials at Johnson’s Island to remove all prisoners of war “now held in close confinement in irons” and place them “on the same footing as other prisoners of war.”3

Despite efforts at distinction, prisoners of war still endured punishments commonly used to correct criminals. Some suffered these punishments for misbehavior during captivity, while others experienced them as a matter of policy in accordance with the rules of war. Some prisoners of war were sent outside of their prisons to work, a punishment reminiscent of convict leasing systems that began in the antebellum period and increased in the post-war era, most predominantly in the South. Many inmates at Castle Thunder and at Old Capitol Prison were sent to labor on the public works to save their captors’ government money while Andersonville inmates captured during escape attempts found themselves at work on a chain gang. Many captives consequently admitted to feeling like criminals even though they were held in military prisons and guilty merely of the “crime” of fighting for the enemy.4

Regardless of the fact that military law drew a distinction between prisoners of war and common criminals, many prisoners of war could not shake the negative stigma of incarceration. By the time of the Civil War, many Americans associated imprisonment with criminality and depravity since incarceration as punishment developed during the first half century, and prisoners of war often could not divorce themselves from that feeling. One unidentified inmate at the Old Capitol lamented, “I’m doomed, a felon’s place to fill,” on the prison wall, which may have been the only sympathetic outlet he had for his feelings. Captain E.C. Saunders of the First North Caroline Union Volunteers similarly characterized the plight of some of his captured men as he complained that they “were treated as felons of the deepest dye,” not as prisoners of war, as they languished in Castle Thunder. Camp chase inmate William Duff perhaps summed up imprisonment most succinctly: “Let that prison life be what it is,” he penned, “it may be of war or criminal or by quarantine or detention in some way . . . but being deprived of liberty and freedom is a terror and a horror to anyone.” Duff’s words suggest that regardless of the institution, imprisonment had a leveling affect. Nineteenth-century inmates – both criminals and prisoners of war held – had some similar experiences of confinement: both, in many instances, were compelled to the same type of labor, suffered from isolation, and longed for the day when freedom would dawn. These examples only barely begin to reveal that story, and there is certainly much more to tell.5

Angela M. Zombek is Assistant Professor of History at St. Petersburg College. Her manuscript, “Penitentiaries, Punishment, and Military Prisons: Familiar Responses to an Extraordinary Crisis during the American Civil War,” is under contract with Kent State University Press.

1 Record Group 393, Part 4 Entry 671, Guard Reports of the Depot of Prisoners at Johnson’s Island, Feb. 1862-July 1865, Vols., 338, 339, 340, National Archives and Records Administration I, Washington, D.C. [hereafter cited as NARA I]; “Island History – Civil War Era Guard Garrison,” Depot of Prisoners of War on Johnson’s Island, Ohio. Accessed May 23, 2013, http://www.johnsonsisland.org/history/war_guards.htm.

2 John Henry King, Three Hundred Days in a Yankee Prison: Reminiscences of War Life, Captivity, Imprisonment at Camp Chase, Ohio (Atlanta: Jas. P. Daves, 1904), 83-84; Mark Colvin, Penitentiaries, Reformatories, and Chain Gangs: Social Theory and the History of Punishment in Nineteenth-Century America (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1997), 90; Dario Melossi and Massimo Pavarini, The Prison and the Factory: Origins of the Penitentiary System, trans. Glynis Cousin (Totowa, NJ: Barnes & Noble Books, 1981), 158.

3 General Orders No. 100: The Lieber Code (April 24, 1863), Art. 76, The Avalon Project, accessed June 21, 2012, http://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/lieber.asp; Revised Regulations for the Army of the United States, 1861 (Philadelphia: J.G.L. Brown, Printer, 1861), 126; Flory, Prisoners of War, 17-18, 80-81; William Hoffman Circular September 3, 1864, Record Group 393 Part 4, Entry 656 “Letters Received 1864-1865 Johnson’s Island.” NARA I.

4“Local Matters: Current Items,” Richmond Daily Dispatch, September 8, 1862, accessed March 14, 2010, http://dlxs.richmond.edu/d/ddr. “Off for the Coal Mines,” Richmond Daily Dispatch, February 23, 1864, accessed March 14, 2010, http://dlxs.richmond.edu/d/ddr. Montgomery Meigs to Henry Halleck, March 23, 1863, O.R. Series II, Vol. 5, 385. Robert S. Davis, “Escape From Andersonville: A Study In Isolation and Imprisonment,” The Journal of Military History, Vol. 67, No. 4 (Oct., 2003), 1075.

5 D.A. Mahoney, The Prisoner of State (New York: Carleton, 1863), 152-159; E.C. Sanders to Maj. Gen. J.G. Foster, April 24, 1863, O.R. Series II, Volume 5, 518-519; W.H. Duff, Six Months of Prison Life at Camp Chase, Ohio, 3d ed. (Clearwater, SC: Eastern Digital Resources, 2004), 5.