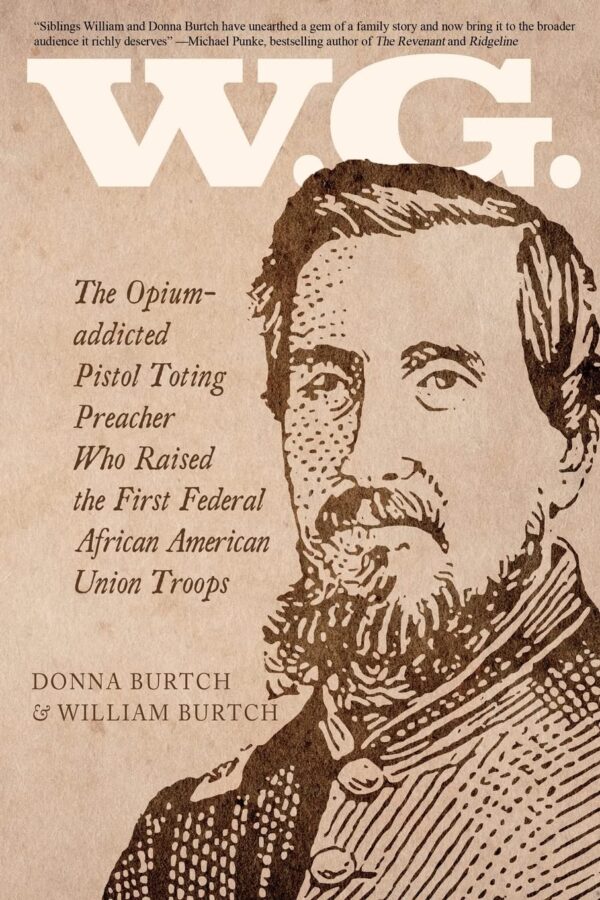

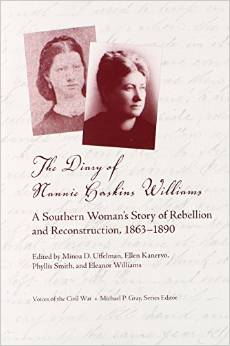

The Diary of Nannie Haskins Williams: A Southern Woman’s Story of Rebellion and Reconstruction, 1863-1890 edited by Minoa D. Uffelman, Ellen Kanervo, Phyllis Smith, and Eleanor Williams. University of Tennessee Press, 2014. Paper, ISBN: 978-1621900382. $34.95.

In February of 1863, seventeen-year-old Martha Ann Haskins began a diary in Clarksville, Tennessee. Nannie—as she was known to friends and family—felt glad to have a diary to be her confidante, noting, “Now [I] have got one, I feel like I can come here, as to an old friend, and lay my heat open” (4). Between war-torn 1863 and January of 1890—a full twenty-seven years—Nannie wrote in her “book” about anything from the weather to what she was reading, from guerillas to lost love, and from motherhood to financial loss. With The Diary of Nannie Haskins Williams: A Southern Woman’s Story of Rebellion and Reconstruction, 1863-1890, the diary’s editors make a lively, intelligent, and engaging woman’s diary available to readers in one volume for the first time.

In February of 1863, seventeen-year-old Martha Ann Haskins began a diary in Clarksville, Tennessee. Nannie—as she was known to friends and family—felt glad to have a diary to be her confidante, noting, “Now [I] have got one, I feel like I can come here, as to an old friend, and lay my heat open” (4). Between war-torn 1863 and January of 1890—a full twenty-seven years—Nannie wrote in her “book” about anything from the weather to what she was reading, from guerillas to lost love, and from motherhood to financial loss. With The Diary of Nannie Haskins Williams: A Southern Woman’s Story of Rebellion and Reconstruction, 1863-1890, the diary’s editors make a lively, intelligent, and engaging woman’s diary available to readers in one volume for the first time.

A number of scholars (and Ken Burns too) have used Haskins’ diary to describe experiences of the Civil War in terms of occupation, death and mourning, women’s views of the Confederacy, and to chart how intellectual, social, and religious life changed during the war. Before this edition, however, the Civil War and postbellum diaries were housed separately at the Tennessee State Archives and The Southern Historical Collection at the University of North Carolina. The editors have brought together the volumes and painstakingly annotated the references, events, and people within its pages in this valuable addition to the University of Tennessee’s excellent Voices of the Civil War Series.

This edition of Nannie Haskins’ diary will be of certain use for scholars of the Civil War, but is an extremely rich source for other topics as well. In the earlier volumes of her diary, Williams’ writing offers a young woman’s perspective on the experience of occupation and war, but also of courtship, friendship, education and reading, and family life. Haskins is funny and often eloquent, though she interrupts her complex ponderings with girlish worries and frustrations. Her descriptions of occupied Clarksville show that she and her peers made the most of their situation, participating in tableaux, soldier relief societies, and a number of parties and plays. In fact, Haskins and six of her friends formed the “Mullen Stalks”—a group who attended class taught by Dr. McMullen at First Presbyterian Church. The “Stalks” organized lectures, presented plays, and offered emotional and intellectual support during times of war.

Like many diarists at the time, she reported the spotty news of the war around her and consistently recorded the injuries and deaths of people in her life—including her brother Robert’s death at Camp Douglas in 1862. She wrote two years after his death, “I never think of him but what a dark prison rises before me with him incarcerated therein upon his deathbed. Oh horrors! I wish this dark picture would be obliterated from my memory” (75). In April of 1865, Nannie dispassionately recorded Lee’s and Johnston’s surrenders, the assassination of Lincoln, and Booth’s death, along with reports about her other brother, Ben, who had been captured at Gettysburg and paroled from Johnson’s Island Prison.

After three years of silence, Nannie’s diary picks up again in 1869. During the gap, Nannie experienced a number of serious changes: her father died, and she and her mother moved from Clarksville to north of Graysville, Kentucky, which felt remote and rural. In these later journals, we see Nannie truly transform from young lady to fiancé, wife, and mother. Soon after moving, Haskins’ much older cousin, widower Henry Philips Williams, began courting her. In August of 1869, Nannie wrote, “I am no longer my own but have given myself away!…I am engaged…to one who loves me with great ardor & devotion & he has my first love” (139). Upon her marriage to Williams, Nannie became stepmother to four children—to which she and Henry would add four of their own. Over the next twenty or so years, many of Nannie’s journal entries concern her eight children and the financial concerns of raising so large a brood during times of serious economic insecurity for farmers. In fact, her financial concerns became the central theme of this volume of the diary.

Despite the focus on financial issues, these journals are also very revealing of how former Confederates moved on with their lives following their devastating defeat. Nannie remembered a number of friends and experiences in Clarksville fondly but showed Lost Cause sentiment or romanticized memories of the Confederacy very infrequently. Instead, the pages showed lasting grief over her father’s death, a consistent connection with national and local events (such as President Garfield’s assassination), and an ever-present interest in intellectual growth—particularly through reading material. These volumes will prove very helpful to scholars interested in seeing the diary as a genre of writing, for Williams uses these pages not only as a confidante and emotional comfort, but as a commonplace book—recording quotes she liked and chronicling her own efforts at authorship.

The diary’s editors have truly brought this valuable source to life with an excellent introduction and conclusion, nearly one hundred pages of endnotes, two appendices addressing military officers and installations mentioned in the diary, and a number of photographs and diagrams. The editors also weave other diaries, newspapers, and letters into the endnotes to further explain content in Williams’ journal, helping the reader to understand how her reactions fit with broader interpretations and viewpoints. The only complaint some readers may have with the editors would be their decision to alter spellings, minor formatting, and other errors and inconsistencies. Still, this would be more a critique of personal preference. Overall, this diary will be an interesting and captivating read for scholars, students, and anyone with an interest in the nineteenth-century South.

Katherine Brackett Fialka is working on a Ph.D. in History at the University of Georgia.