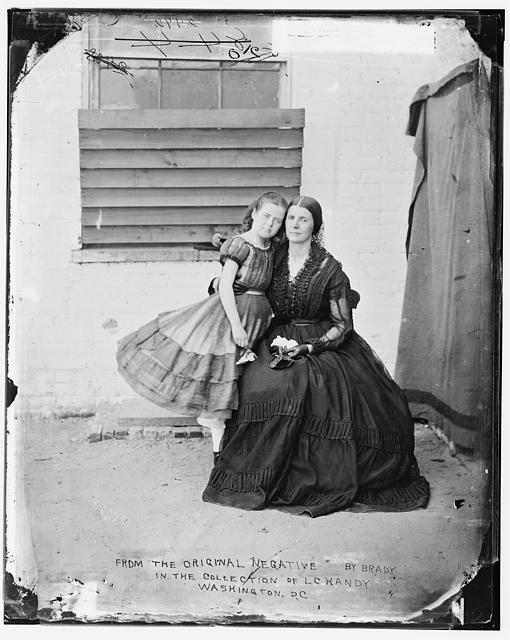

Good afternoon! Today’s Women’s History Month tribute is of Rose O’Neal Greenhow—also known as “Wild Rose”—the famed Confederate spy. Born in Maryland in 1817, little is known of her early years. However, Rose married Dr. Robert Greenhow in 1835 and then moved to Washington, D.C. where she befriended President James Buchanan and John C. Calhoun. Despite being widowed in 1854, Greenhow retained her position among the Washingtonian elite.

During the Civil War, Rose spied for the Confederacy, writing ciphered messages and providing intelligence about Union military plans. President Jefferson Davis even credited Rose with the rebel victory at Manassas as it was rumored that she sent a secret message to General Pierre G.T. Beauregard about federal troop movements. In 1862, Allan Pinkerton, head of the U.S. Intelligence Service, placed Greenhow under house arrest before transferring her to the Old Capitol Prison. Despite her incarceration, Rose continued to collect intelligence and send encoded messages. Eventually she was exiled to the Confederacy and then sent on a diplomatic mission to Europe in 1863. Two months after arriving in London, Greenhow published her memoirs: My Imprisonment and the First Year of Abolition Rule at Washington. During her return voyage to the South in 1864, her ship—the blockade runner, the CSS Condor ran aground and Rose drowned while trying to escape. In October of 1864, Greenhow was buried with full military honors in the Oakdale Cemetery of Wilmington, North Carolina.

Below is an excerpt from Greenhow’s memoir:

In short, two years of terrible war, equivalent, an age of quiet life, have passed through the existence of us all, leaving a deep and ineffaceable track. Between us and those former friends there is a gulf deep and wide as eternity; and under these circumstances I have felt myself at liberty to be much more unreserved in the narrative of my personal recollections: suppressing, in fact, nothing which I thought would be either interesting or useful to my Confederate countrymen – except only when reserve was dictated by self-respect, or by the duty of avoiding disclosures which might compromise the safety of certain Federal officers, whom I induced without scruple as will be more fully seen in the following pages, to furnish me with information, even in my captivity, which information I at once communicated with pride and pleasure to General Beauregard, then commanding the Confederate forces near Washington. Whatever may be thought of the conduct of these Federal officers in betraying to an avowed enemy secrets material to their own Government, it will readily be admitted that after having made this use of them I should not have been justified in naming them, or affording a clue by which they could be discovered.

If, in detailing conversations which passed either with me or in my presence, before or after my arrest, I may be thought to have exhibited too great bitterness, it is hoped that the circumstances under which I found myself may plead my excuse. It will be seen that I was well aware from an early period of the dark designs of the Abolition leaders at Washington, and that while they were holding publicly the language of patriotic zeal for the constitution and the law, they were already meditating, and preparing, all the dreadful scenes of lawless outrage and spoliation which have since that time rendered their names odious to the whole world It was well known to me what fate they were reserving for my own native State, and what diabolical agencies they were setting to work over all the country, both to destroy the Confederate States and to crush out the liberties of the North. The chief projectors of all these horrors, too, were well aware that I knew their plans and machinations intimately; and that, weak woman as I was, I possessed both the means and the spirit to throw serious obstacle in their way. Hence the keen and jealous surveillance by which my every motion was observed and noted, even long before my arrest. Hence, also, the useless series of torments and provocations to which I was subjected – the changes in my place of imprisonment, and the many attempts to entrap me into a betrayal of myself or the Confederate cause. Hence the long and wearisome captivity, to break my spirit, or goad me into undignified bursts of indignation – in all of which I trust I may flatter myself that they signally failed. Satisfied thoroughly of the justice and sacredness of our great cause, thinking only of the gallant struggle into which my kindred had thrown themselves, I was enabled, not only to ‘possess my own soul’ and keep my own counsel, but also to establish and maintain a continuous correspondence with Virginia, and reveal certain contemplated military movements of enemy in time to have them thwarted by our generals. For this I do not desire to take any special credit in the eyes of the public. I only performed my duty, and have already been gratified by the thanks of those who best can judge of the services which I endeavoured to render; and the matter is mentioned here merely as one of the reasons why it has been thought that a narrative furnished by one who enjoyed such opportunities of observation may be found not uninteresting.

Source: Greenhow, Rose O’Neal, “My Imprisonment and the First Year of Abolition Rule at Washington,” electronic edition courtesy of Documenting the American South, The University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill.

Image Credit: Library of Congress.