Jack O’Connell and Michelle Dockery in a scene from the Netflix miniseries Godless. As in previous depictions of the postwar West, the Civil War factors little into the show’s characters and stories.

When I sat down to watch the new Netflix miniseries Godless, a Western set in 1885 New Mexico, I was curious to see whether any Civil War veterans would show up. In the first two of the show’s seven episodes, there were lingering shots of the high desert, violent massacres, lone horsemen, and flashbacks to the dismal childhoods of orphaned boys—but no Civil War veterans. Then, in the third episode, viewers are introduced to the residents of Blackdom. The men are all former Buffalo Soldiers, African Americans who served in the 10th Cavalry Regiment in the years after the war, riding out on campaigns against Native Americans throughout the Great Plains to the Southwest. Only one of them still wears his blue coat, and after a white man who comes through town in the next episode seems starstruck by him, we learn that the former soldier, John Randall (Rob Morgan)—who was a real historical figure—is a “war hero.”

This is likely a reference to Randall’s fight against the Cheyenne in 1867, when he fended off a large group of warriors by himself until reinforcements arrived, rather than an allusion to his service in the Civil War. We don’t find out for sure, however, because there is no further conversation about it. The rest of the good guys in Godless aren’t old enough to have been Civil War soldiers. Although the bad guy (Frank Griffin, played by Jeff Daniels) wears a grey coat, his pathology is explained not by his service in any Civil War army but instead by the traumatic loss of his entire family to Mormon attackers at the Mountain Meadows Massacre in 1857.

The marginality of the Civil War in Godless is not unusual. In the vast majority of film and television Westerns, the region’s wooden towns and windswept cattle ranches exist in the post-war world: a time of mule-drawn wagons but also railroads, telegraph wires, and repeating rifles.

The war stories in Westerns are intensely personal battles, usually driven by acts of betrayal: The cowboy rides out into the West to seek revenge upon those who wronged him.

Every now and again, however, the deeds that provoke this cycle of violence occur during the Civil War. The ex-Confederate hero (Anson Mount) of the recent AMC show Hell on Wheels, for example, heads west to hunt down the Union guerrillas who killed his wife and children.

Anson Mount (center) as Cullen Bohannan in the AMC show Hell on Wheels

These acts of revenge are often depicted as ways for Confederate veterans to heal from the war’s traumas. In the classic film The Searchers (1956), Ethan Edwards (John Wayne) appears on his family’s Texas doorstep in 1868, still wearing his Confederate uniform, CSA belt buckle and all. “Uncle Ethan” refuses to talk about the war or how he’s passed the years since. After a band of Comanches attacks the family ranch, killing almost everyone and taking his niece hostage, Ethan tracks the band and its chief, Scar (Henry Brandon), for five years. This epic journey gives him a sense of purpose, a way to focus on the future rather than the past.

The television show The Rebel (1959) set up a similar plot for its protagonist, Johnny Yuma (Nick Adams), a Confederate private who reappears in his hometown in 1867, also wearing his Confederate uniform. After finding his father dead and the town in the hands of nefarious mine owners, Johnny single-handedly kills them all and takes back the town for its former inhabitants. Then he moves on, roaming the West and initiating his own private wars against a series of foes.

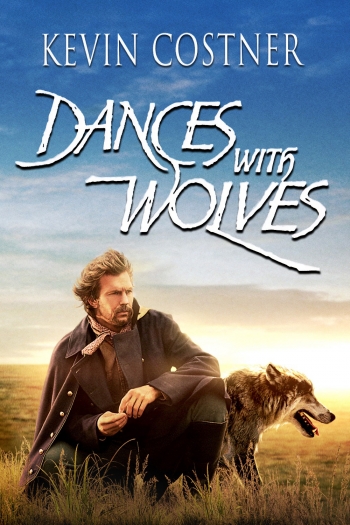

In Dances with Wolves (1990), Lieutenant John Dunbar (Kevin Costner) is one of the rare Union veterans to search for healing in the West. The first part of the film takes place during the Civil War, establishing Dunbar’s bravery in battle and his wartime traumas. He ultimately bonds with the Lakota Sioux who live near his frontier post, and he refuses to take part in the Army’s campaigns against them.

Most Union veterans in Westerns are not so noble. They are more often dodgy characters who were drafted or who deserted or otherwise behaved badly during wartime. In the HBO show Westworld—which imagines a fantasy “park” populated by robots playing gunfighters, gamblers, prostitutes, and Indian warriors—Union soldiers appear at first only at the “southern” edge of the park, fighting skirmishes with a handful of “Confederados.” By the end of the first season, however, the war narrative in this part of the park has changed, and the Union soldiers have been converted into murderers of innocents in the town of Escalante, and then into a band of stock Western vigilantes.

Recent divergent depictions of Union and Confederate soldiers and veterans may reflect a turn by some historians and writers to the “dark history” of the Civil War—an approach that emphasizes the violence and destruction of the conflict, as perpetrated and experienced by both sides. Film and television writers have also taken a cue from the Lost Cause narrative, in which Confederate defiance is the more sympathetic and compelling story. Additionally, their “common man” protagonists with unconventional approaches to violence illustrate Matthew Hulbert’s argument in his recent book, The Ghosts of Guerrilla Memory (2016), that Confederate bushwhackers were quite easily converted into Western heroes in American popular memory.

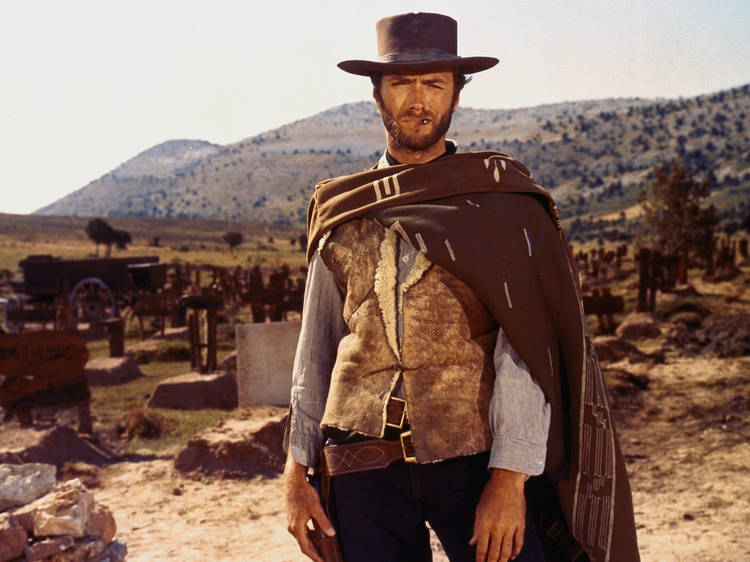

Almost no Westerns depict actual Civil War engagements in the West, however. The most well-known exception is Sergio Leone’s The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1966), which purportedly takes place in New Mexico during Confederate general Henry Hopkins Sibley’s campaign in 1861–1862. I’m not usually a stickler for historical accuracy in films; this medium requires only that the historical action be credible in order to situate the plot and characters. But The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly’s depiction of Civil War New Mexico is just, well, bonkers. It’s as if the screenwriter read a synopsis of Sibley’s campaign and then drank a bottle of whiskey before sitting down to write the film. The dates are wrong; there are bombings of towns (and, famously, a giant bridge) that never happened; the geography is wonky; and the three main characters (played by Clint Eastwood, Eli Wallach, and Lee Van Cleef) end up in a POW camp that never existed. Each of the men dons a Confederate or a Union uniform at some point during the film, but only in order to escape from the authorities or to obscure their real goal, which is to find a cache of hidden gold stolen from Confederate coffers. In The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, the war is merely a convenient way to inject chaos into a standard plot of revenge and pursuit.

Clint Eastwood in The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

The problem with all of these erasures and obfuscations in Westerns is that it leaves most Americans believing that there was no Civil War in the West. Like most Civil War history books and college courses, these forms of popular culture suggest that the war was confined to battlefields east of the Mississippi River. Onscreen, the West is untouched by the conflict, existing only to welcome northerners and southerners after the fact, reuniting them as Anglo “settlers” who seek to make new lives for themselves.

But there was, in fact, a Civil War in the West. Both the Union and the Confederacy wanted control of the region’s gold mines and its access to ports in the Pacific and the Gulf of California. Two armies—one made up of U.S. Army regulars, Anglo miners-turned-volunteers, and Hispaño volunteers and militias, and the other made up entirely of Anglo and German Texans—fought one another up and down the Rio Grande in 1861–1862. Along the way, they both suffered raids on their camps by Navajos and Apaches; once the Union army had vanquished the Confederate Texans, they turned their attention to these Native Americans and waged war against them in the name of the United States. The battles in this region during the Civil War determined the fate of the West, and the future of the nation.

None of this is apparent in any American Western, from the 1950s to today. A small group of Civil War historians—including myself—is working to counteract these visions by writing the war back into the history of the West, and vice versa. Maybe someday I’ll sit down to watch a Western and see the region’s very real Civil War history conveyed in its plot and characters—along with, of course, lingering shots of a lone horseman against the desert landscape.

Megan Kate Nelson is a writer and historian who lives in Lincoln, Massachusetts. She is the author of Ruin Nation: Destruction and the American Civil War (2012) and Trembling Earth: A Cultural History of the Okefenokee Swamp (2005).

This article appeared in the Spring 2018 (Vol. 8, No. 1) issue of The Civil War Monitor.