Lincoln and the Natural Environment by James Tackach. Southern Illinois University Press, 2019. Cloth, IBSN: 9780809336982. $24.95.

“Lincoln was a close observer of nature,” remarked the journalist Noah Brooks, the president’s White House confidant turned celebrated biographer. “He used natural objects to complete his similes.” It is thus somewhat remarkable that the sprawling Lincoln bibliography does not include a sustained, stand-alone treatment of the president’s “relationship to the natural environment.” James Tackach, a professor of English at Roger Williams University, attempts to remedy that gap with this recent entry in Southern Illinois University Press’s Concise Lincoln Library series. In such a short compass, Tackach cannot be comprehensive; nonetheless, he capably outlines what a full-scale environmental biography of the sixteenth president might look like. The author does not “advance the argument that Lincoln was a ‘green’ president,” but does suggest powerfully that the president’s ideas about the environment “evolved” over time.

“Lincoln was a close observer of nature,” remarked the journalist Noah Brooks, the president’s White House confidant turned celebrated biographer. “He used natural objects to complete his similes.” It is thus somewhat remarkable that the sprawling Lincoln bibliography does not include a sustained, stand-alone treatment of the president’s “relationship to the natural environment.” James Tackach, a professor of English at Roger Williams University, attempts to remedy that gap with this recent entry in Southern Illinois University Press’s Concise Lincoln Library series. In such a short compass, Tackach cannot be comprehensive; nonetheless, he capably outlines what a full-scale environmental biography of the sixteenth president might look like. The author does not “advance the argument that Lincoln was a ‘green’ president,” but does suggest powerfully that the president’s ideas about the environment “evolved” over time.

Brisk chapters move chronologically through Lincoln’s life and times. In his early years, Lincoln learned “profound and emotionally painful lessons about nature’s power over life.” On the Indiana frontier, “milk sickness,” the after-effect of the poisonous “snakeroot plant,” claimed Lincoln’s mother and several relatives. Lincoln was not a little self-conscious about his backwoods upbringing, and he openly resented exhausting manual labor and farm work.

Those lessons, the author speculates, may have played a role in Lincoln’s quest to “tame” nature through inventions and internal improvements. As a Whig state legislator and later United States Congressman, support for internal improvements was his political creed. “Eager to embrace [the] new industrial order,” the future president did not give much thought to the environmental consequences of the new turnpikes, canals, and railroads that cleaved across and gouged through the land. “Not until a year or two into his presidency,” Tackach writes, “would Lincoln begin to consider some of the negative effects of industrialization…and develop some political strategies for dealing with those effects.”

Still, it is fair to say that nature annexed Lincoln’s thought to a considerable degree. He marveled at the beauty of Niagara Falls and penned a wistful ode to his “childhood home.” Even more significantly—and as Brooks recalled—he “used anecdotes from the natural world to explain military and political strategy, clarify his political positions, and pose or solve problems.” The author inventories a number of Lincoln’s metaphors, parables, and anecdotes involving nature—perhaps none so important as the Gettysburg Address, which, as Gabor S. Boritt and other historians have pointed out, “moves with the rhythms of the natural world.”

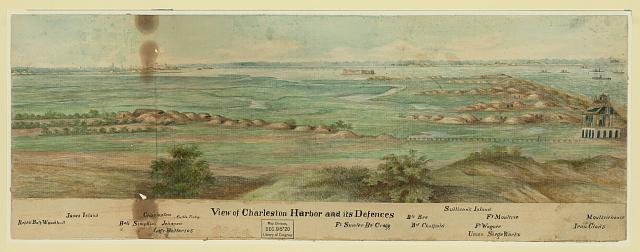

Tackach devotes a chapter to the Civil War and its devastating environmental effects, drawing on important recent scholarship by Lisa Brady, Mark Fiege, Jack Temple Kibry, and Megan Kate Nelson. Echoing the findings of other scholars, he suspects that the conflict’s “environmental carnage” is at least “partly responsible…for the advancement of a nature preservation movement in the United States.” Providing future generations with an index of his developing views on stewardship of the land and conservation of natural resources, Lincoln established the Department of Agriculture, signed the Morrill Act, and affixed his signature to the Yosemite Valley Grant Act—the latter a “forerunner” of “governmental initiatives to protect the natural environment.” The significance of these developments can hardly be exaggerated; however, engagement with the work of Adam Wesley Dean would help the author to contextualize more fully these developments in the larger histories of the Republican Party and antislavery politics.

Hopefully, this short but stimulating book will inspire more scholarship on the relationship between Civil War Americans and the natural world. An environmental history of Reconstruction would pay enormous dividends, as would a study of how “heal[ing] the South’s war-damaged natural landscape” contributed (or not) to sectional reconciliation and Civil War memory. When Lincoln spoke about “binding up the nation’s wounds,” he almost certainly counted the landscape among them.

Brian Matthew Jordan is the author of Marching Home: Union Veterans and Their Unending Civil War.