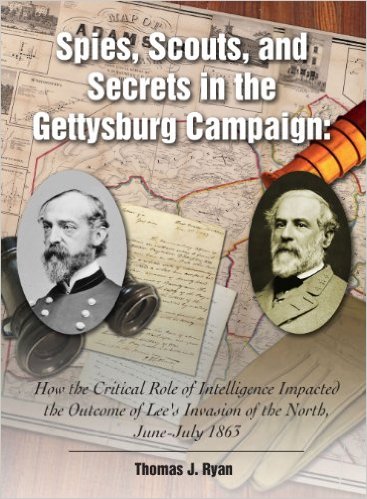

Spies, Scouts, and Secrets in the Gettysburg Campaign by Thomas J. Ryan. Savas Beatie, 2015. Cloth, ISBN: 978-1-61121-178-8. $32.95.

Intelligence, or the lack thereof, may have played the single-most important role in the outcome of the Gettysburg campaign. Despite this fact, the tens of thousands of pages written about Gettysburg have focused on the minutiae of both army’s movements, the histories of individual units, and examinations (and re-examinations) of unit commanders. Thomas J. Ryan does a masterful job of combatting this ironic lack of knowledge in Spies, Scouts, and Secrets in the Gettysburg Campaign: How the Critical Role of Intelligence Impacted the Outcome of Lee’s Invasion of the North, June-July, 1863. Ryan sets out to examine the Gettysburg campaign “day-by-day, hour-by-hour from mid-May to mid-July 1863 focusing on the movements and objectives of their opponents, and maneuver to gain the advantage,” and he certainly succeeds in doing so (xiv).

Intelligence, or the lack thereof, may have played the single-most important role in the outcome of the Gettysburg campaign. Despite this fact, the tens of thousands of pages written about Gettysburg have focused on the minutiae of both army’s movements, the histories of individual units, and examinations (and re-examinations) of unit commanders. Thomas J. Ryan does a masterful job of combatting this ironic lack of knowledge in Spies, Scouts, and Secrets in the Gettysburg Campaign: How the Critical Role of Intelligence Impacted the Outcome of Lee’s Invasion of the North, June-July, 1863. Ryan sets out to examine the Gettysburg campaign “day-by-day, hour-by-hour from mid-May to mid-July 1863 focusing on the movements and objectives of their opponents, and maneuver to gain the advantage,” and he certainly succeeds in doing so (xiv).

Essentially, Ryan tells a tale of two halves. As Robert E. Lee maneuvered the Army of Northern Virginia into position for an invasion of the North, the federals lost track of Lee’s army almost completely. Ryan directs the bulk of his criticism throughout the campaign at Alfred Pleasanton, who failed time and time again to gather sufficient intelligence with which to advise Joseph Hooker and later George Meade. Ryan explains that both northern and southern cavalry units were responsible for gathering and disseminating information or misinformation. Unfortunately for Hooker, the commander of the Army of the Potomac during the initial phases of Lee’s invasion, his primary cavalry commander preferred to engage Jeb Stuart’s Confederate cavalry as some sort of test of bravado. This allowed Lee’s three corps under Generals Ewell, Hill, and Longstreet to slip across the Potomac River before encountering Union scouts.

Lee’s luck turned for the worse when Stuart’s cavalry got separated from the main body of the Confederate army. Ryan blames the ineptitude of Beverly H. Robertson’s cavalry, who remained behind to watch the Union army. Stuart instructed him to provide Lee with “critical intelligence” and to help screen the army’s movements, but he failed to do so—endangering Lee’s entire army (244). Stuart certainly bears some of the responsibility for entrusting this important task to one of his subordinates, but Robertson essentially ignored his orders and gave Hooker almost a two-day start before Lee learned of the marching Army of the Potomac.

Both armies relied heavily on cavalry for their intelligence capabilities, but northern leaders stepped up their efforts, establishing the Bureau of Military Intelligence under Colonel George Sharpe to act as their intelligence arm. At times, Hooker and Meade both failed to take advantage of these capable scouts, spies, and interrogators, yet they possessed a powerful tool that Lee did not. Lee preferred to rely almost exclusively on his trusted cavalry commander and his own interpretation of data gathered by scouts and spies. Essentially, this put even more weight on his shoulders and led to a severe lack of information during the campaign when Lee lost contact with Stuart. When Lee lost contact with Stuart, the noticeable “absence of an intelligence staff at [his] headquarters prove[d] to be detrimental” (96). As a result, Lee lacked critical intelligence that he desperately required. Essentially, Lee marched into Pennsylvania almost entirely blind.

Ryan maneuvers masterfully through the details of northern and southern movements, examining reports and illustrating the situation on the ground as both army commanders almost felt their way to the fields surrounding Gettysburg. The author does a very good job of showing the confusion and dangers that nineteenth-century military leaders encountered. Unable to communicate swiftly, leaders had to write down or encrypt messages that they sent to fellow officers. Unfortunately, these fell into enemy hands on occasion. Lee spent the morning of July 3 awaiting an answer from Richmond about the possibility of shifting troops out of southern Virginia to present a threat to Washington, D.C. He believed this tactic might encourage Washington to shift soldiers away from Meade’s Army of the Potomac. Unbeknownst to Lee, the reply that Richmond could not agree to Lee’s request had fallen into Meade’s hands, affirming that he would only have to face the forces currently engaged at Gettysburg.

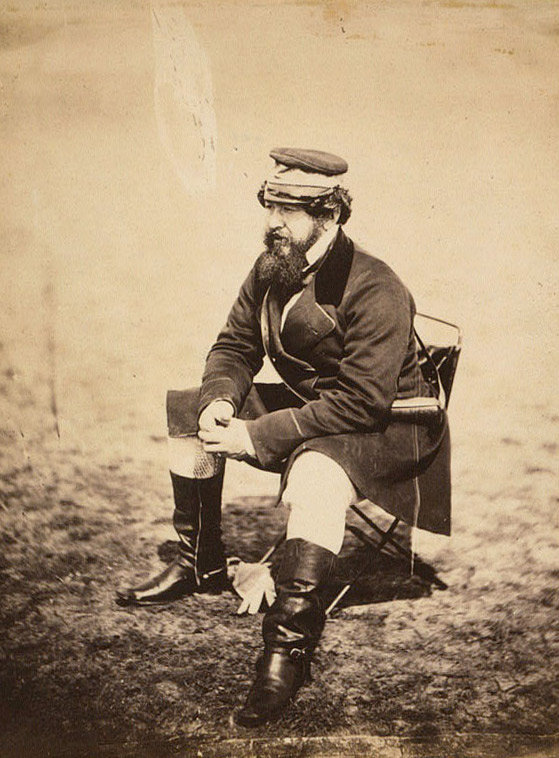

This book offers much to recommend to military historians and students of the battle of Gettysburg who want to investigate a well-written and deeply researched analysis of intelligence during this vital campaign. The book contains a good collection of photographs of important actors and maps that detail specific movements or moments in time. Choosing to organize the book in a rigidly chronological fashion allows the reader to make sense of the cause and effect nature of this chaotic environment, as commanders of both armies negotiated the movements. Ryan has provided a template that historians may use to examine the role of intelligence during other campaigns, and we should all look forward to seeing those develop as well.

Nate Buman received his Ph.D. from Louisiana State University and is currently employed as the Manager of the Shelby County Historical Museum in Harlan, Iowa. Buman is the former editor of Civil War Book Review.