The Robert E. Lee monument in Charlottesville’s Emancipation Park

On August 13, a statue of Robert E. Lee took center stage in the struggle over the meaning and legacy of the Civil War. That day a “Unite the Right” rally of self-proclaimed white supremacists, neo-Nazis, Ku Klux Klan members, anti-Semites, and neo-Confederates protested the city’s decision to remove an equestrian statue of Lee from a public park. The rally erupted in violence, killing one counterprotester, Helen Heyer, and injuring many others. Since then, a black shroud has been draped over the statue until the city decides exactly what to do with it.

In response to this shocking and bloody event, many Americans now want Confederate memorials in their communities or on their campuses removed from sight. But where should they go? Any place where they cannot offend anyone seems to be the most popular suggestion. Yet such a course may be self-defeating. If you don’t destroy these monuments that invoke passionate emotions in blacks and whites, then the symbols of slavery and white supremacy will still exist, and as long as they do Americans will view them as either noxious or heroic, no matter where they happen to be physically located.

Many Americans have focused on Robert E. Lee statues—most of them located in the South—as the best candidates for removal or disposal. They do so because Lee has become, since the Civil War, the general in chief of Confederate monuments. I certainly understand the symbolism that Lee memorials possess. Despite all myths to the contrary, Lee was intimately entangled with the institution of slavery, to the point where rumors are now flying that, like Thomas Jefferson, he fathered at least one biracial child, perhaps more. Lee asserted that he hated slavery, yet he treated slaves as property and beasts of burden, just as other southern slaveowners did, especially when it came to running down fugitive slaves from Arlington, the estate of his deceased father-in-law, George Washington Parke Custis. When the Civil War broke out, Lee fought for the Confederate States of America, which was established to protect and perpetuate the “peculiar institution,” as some Americans euphemistically referred to the system of slave labor and racial control in the South.

As Lee fought to sustain slavery, he also fought to maintain white supremacy, an attitude of superiority that whites in every part of the country, not just in the slaveholding South, held toward people of color. Although Lee, in a letter to his wife dated December 27, 1856, wrote that slavery was “a moral & political evil in any country,” he quickly expressed his belief that “the blacks are immeasurably better off here than in Africa, morally, socially, & physically. The painful discipline they are undergoing, is necessary for their instruction as a race, & I hope will prepare & lead them to better things.” He also believed that everyone must wait until God decided when to free the slaves. No expected date of emancipation could be known to mortal man. It might happen tomorrow or in the next millennium. In short, Lee was not—as some historians and antiquarians have claimed—antislavery in his thoughts about slavery. He was the opposite: an apologist for the peculiar institution and for white superiority.

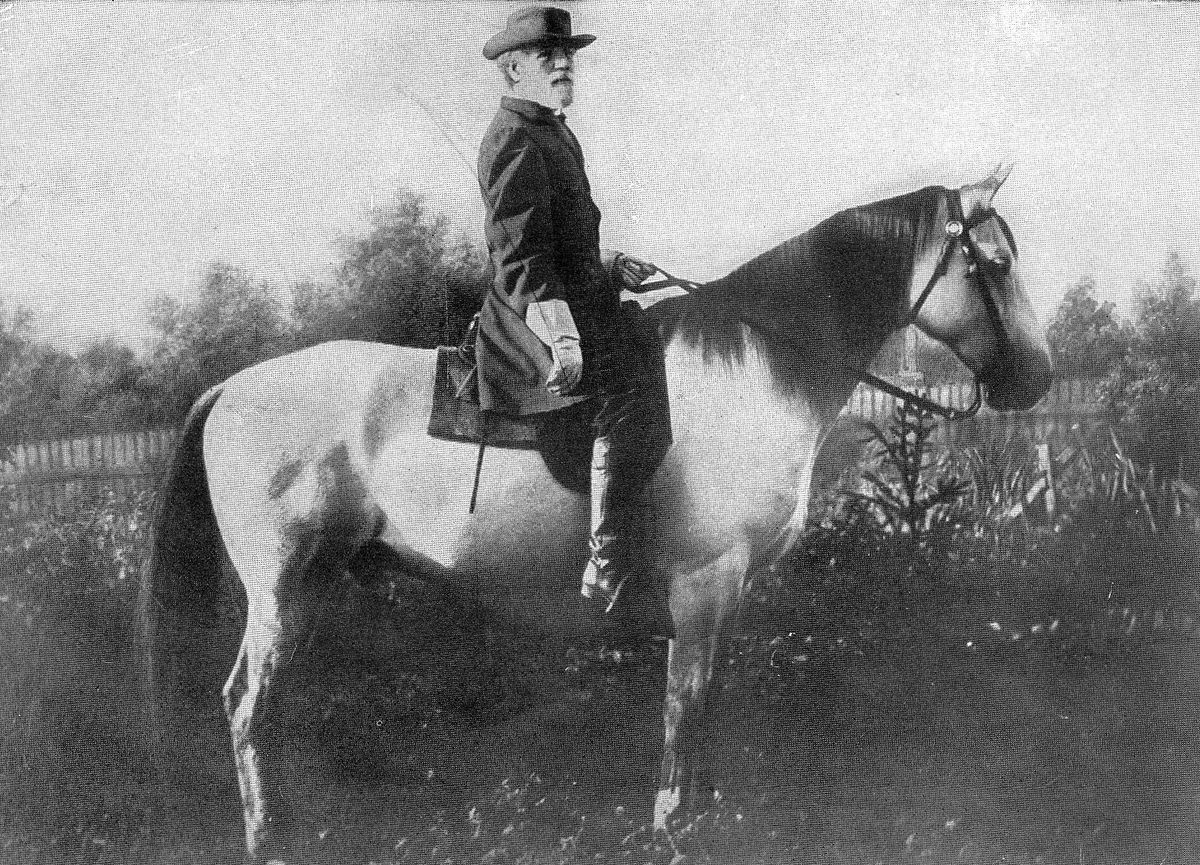

Robert E. Lee mounted on his war horse, Traveller. Despite some claims to the contrary, the famed Confederate general was not antislavery in his thoughts about the “peculiar institution.”

There is another notable problem with Lee and Confederate monuments. Lee was a traitor to his country; even his profession of loyalty to his native state, Virginia, does not absolve him of his treason against the United States. More than once, Lee took solemn oaths, sworn under God, to defend the United States and its Constitution from all enemies. In April 1861, soon after he had received a colonel’s commission in the U.S. Army, and days after he had been offered command of the Union army by a Lincoln surrogate, Lee decided to resign his commission and accept a promotion to major general in the Virginia state militia. Eventually he was mustered into service as a Confederate general. If Lee believed he could simply resign his commission in the U.S. Army to free him from the burdens of his oath to the United States, he was wrong. The oath taken by Lee did not specify that an individual’s loyalty—or the efficacy of the oath—ended when one left federal service. It presumed, in fact, that the oath was binding until one’s death, even if an individual separated from active federal service.

Lee as he appeared after the end of the Civil War. While President Gerald Ford restored Lee’s rights as a U.S. citizen in the 1970s, the general has never received a presidential pardon.

When Lee broke his oath to follow his native state out of the Union, he committed an act of treason. That act was compounded by the fact that he also took up arms against the United States, which also constituted treason. Although Lee showed contrition after the war and promoted reconciliation between North and South, he was indicted for treason by a grand jury in May 1865. Nothing ever came of the indictment, perhaps because Lee signed an oath of allegiance to the United States five months later. Ulysses S. Grant supported a pardon for Lee, but President Andrew Johnson never issued one. More than a hundred years later, in 1975, Congress, in a joint resolution signed by President Gerald R. Ford, reinstated Lee’s full rights as a U.S. citizen. It’s significant, though, that Lee still has never received a presidential pardon. He purposefully committed crimes against the United States, sought to undermine its sovereignty, and commanded a Confederate army that killed and wounded thousands of loyal Union soldiers. It would appear ludicrous, under those circumstances, for any modern president to pardon Lee for his crimes. Article III of the Constitution states that “treason against the United States, shall consist only in levying War against them, or in adhering to their Enemies, giving them Aid and Comfort.” Lee was never brought to trial for treason or convicted of that offense, but it remains clear that he committed acts that fall within the constitutional definition of treason. Every other Confederate who took up arms against the federal government was also guilty of treason. As a result, many Americans are now demanding the removal of Confederate monuments not only because they perceive them as symbols of hate, but because they also honor traitors.

Should Lee and Confederate memorials be removed from public spaces or be demolished? While it’s true that some memorials have already been moved out of sight, sometimes in the dead of night, I would suggest that the nation slows down, takes a deep breath, and moves more cautiously in the weeks and months to come. The removal of a Lee statue from public display will not wipe out the extreme racial, religious, and political views that are currently in fashion among a small percentage of Americans. The Constitution protects free speech and free assembly for its citizens; at the same time, it does not condone violence or incitement undertaken by those who do assemble and speak freely.

The problem, it seems to me, is not so much the memorials themselves as the symbols that are imposed on them. A statue of Robert E. Lee can symbolize whatever anyone wants it to symbolize. The statue by itself means nothing. It only has the meaning we assign to it.

When I look at a Lee statue, what I see is an artistic impression of a complex man, filled with inconsistencies and contradictions, a man who made the wrong decision when he chose to follow his state out of the Union. After all, he could have resigned from the U.S. Army and taken no part in the war. Tragically, his assumptions, prejudices, and personal ambition led him into treasonous acts. It’s not the decision his idol, George Washington, would have made. Our first president believed in the perpetuity of the Union.

Charlottesville’s Lee statue as it appears today—covered in a black tarp.

Putting a black shroud over a statue or removing it in the dead of night does not accomplish anything, except, perhaps, the stirring up of more divisiveness. We still know that beneath the shroud or in some city warehouse the statue still exists. I’m not making an argument that Confederate memorials should be destroyed by melting them down, just as I would never advise anyone to burn whatever books on the Confederacy he or she owns.

History is malleable because we are forced to interpret it through the eyes of our present. It is also malleable because historical interpretations change over time, reflecting current cultural norms and biases. But what if, 50 years from now, those cultural values shift again and produce a lamentation for the fate of Confederate memorials that disappeared during the second decade of the 21st century? I would argue that if Confederate monuments go missing, one side of Civil War history, to a certain degree, will be lost, though certainly not forgotten. I also believe that without knowing the full story of the Civil War, we cannot possibly understand the social and political chasm that exists between red and blue states today.

In the end, though, the past is the past, and we need to understand it to know how we’ve gotten to where we are today, as a people and as a nation. Confederate monuments, as odious as they might be to some Americans, remind us that there was a time, now a mere 150 years ago, when the country was torn asunder, and a horrific war was fought to insure the primacy of the Union and the elimination of slavery. Instead of removing monuments, they should stay in place as reminders of history, not as clashing symbols of our present social and political concerns. As a people, Americans should find the fortitude, as difficult as it might be to muster, to confront the nation’s history directly without trying to brush it under a rug. If we try to negate the past, with all its deep and haunting meanings, we are only negating ourselves.

Glenn W. LaFantasie is the Richard Frockt Family Professor of Civil War History at Western Kentucky University.