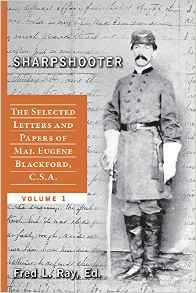

Sharpshooter: The Selected Letters and Papers of Maj. Eugene Blackford, C.S.A. edited by Fred L. Ray. CFS Press, 2016. Cloth, ISBN 978-0-9882435-1-4. $39.95.

Tales of Civil War marksmen have long been mythologized in the popular imagination of the conflict. With advancements in weaponry and industrialization, snipers came of age amid America’s bloodiest war. Fred L. Ray’s latest book, Sharpshooter, offers vivid insights into the colorful exploits of the aristocratic Major Eugene Blackford of the 5th Alabama Infantry. In this, the first of three volumes on the Confederate officer, Ray conveys a comprehensive portrait of the families, fervor, and fears that defined combatants of that generation.

Tales of Civil War marksmen have long been mythologized in the popular imagination of the conflict. With advancements in weaponry and industrialization, snipers came of age amid America’s bloodiest war. Fred L. Ray’s latest book, Sharpshooter, offers vivid insights into the colorful exploits of the aristocratic Major Eugene Blackford of the 5th Alabama Infantry. In this, the first of three volumes on the Confederate officer, Ray conveys a comprehensive portrait of the families, fervor, and fears that defined combatants of that generation.

Moving beyond the mundane routines of camp life, Blackford’s life offers compelling insights into the inner-workings, rivalries, and shortcomings of the Confederate war effort. One key facet within these dilemmas is a noted lack of southern unity before and during the hostilities. Having roots in both Virginia and Alabama, Blackford was readily able to attest to the disparities within Dixie. In a March 10, 1861, letter from Alabama, he wrote of the prewar frenzy in South Carolina: “I can assure you that Gen. Cottondom is no natural ally of Va. I trust that she will form a separate league with the Border states, who are only her natural friends.” Yet, her “people are positively hostile to the Old Dominion. . . . I am finally convinced that I could never live under a government whose Organs were so utterly at variance with all that we in Va. hold sacred” (20). Ultimately, Blackford believed the Cotton Kingdom would bring ruin upon itself.

As war began and Blackford rose through the ranks, he developed unique friendships and compelling camaraderie with young luminaries of the Army of Northern Virginia, including Randolph McKim and Sandie Pendleton. Especially illuminating is Blackford’s relationship with division commander Robert E. Rodes, whose wife burned his personal correspondence following his death. Thus, Blackford’s accounts of the general fill a significant void in the historical record.

Perhaps most interesting are Blackford’s reflections upon slavery and camp servants. In a May 1862 letter to his mother, Blackford wrote, “Please thank father for his trouble in procuring so good a servant as Marcellus, nothing in the world could contribute so much to alleviate my trials” (83). Later, when Marcellus was sent home, Blackford exclaimed, “You can’t imagine how many disagreeable predicaments I am put in by the want of a boy” (116). While Blackford’s letters are devoid of racist rhetoric, his continual search for trustworthy slaves persistently hints at the South’s complete dependence upon the peculiar institution—an addiction Blackford himself elusively alludes to throughout his correspondence.

Blackford described himself as “indifferent” as to the war’s eventual results; however, he passionately admitted fighting for the defense of those at home and was determined “that God is on our side” (67). The young officer also invoked the spirit of history when reflecting upon Virginia’s battlefields. While serving at Yorktown, he wrote, “Providence may intend to achieve the independence of this new republic on the same spot where that of the first was established” (69).

Despite flowery observations of honor and patriotism, military life was nonetheless dreary. Bad coffee, scratchy underwear, heavy wool coats, incessant winter winds, debilitating summer heat, and fears that invariably befell Civil War soldiers accurately reflect many of Blackford’s experiences. As he wrote of federals during a truce following Fredericksburg, the men “seemed utterly sick of the war” (123). Of his experiences at Chancellorsville, the young rebel remarked, “I was exposed to the most awful fire of grape & canister from the enemy’s batteries. . . . Tho’ we have covered ourselves with glory it was at a fearful cost” (165). Prior to the days of military censorship, Blackford did not restrain his views on the war that engulfed him and his men.

While Ray interjects snippets of background information between letter transcriptions, he often neglects opportunities to delve more fully into the rich social and political complexities that dramatically shaped Blackford’s worldview. These omissions include a young man’s torn concepts of loyalty and race amid the tumultuous 1860 election. Furthermore, Ray’s claims of the Blackford family having “abolitionist leanings” (xix) go largely unexplored. Although Mrs. Blackford was a proponent of colonization, her family still retained slaves. The author does not fully examine these contrasting dynamics.

All that said, this lack of context is unlikely to detract from the immense value of Blackford’s correspondence for the learned Civil War reader. His letters strip away the romanticized veneer of the Lost Cause that permeated innumerable veteran memoirs following the conflict. For this reason and more, Sharpshooter is a revealing testament about life and death in the Army of Northern Virginia.

Jared Frederick is a former seasonal park ranger at Gettysburg. He is currently an Instructor of History at Penn State Altoona. Visit his website at www.historymatters.biz.