Lincoln and Emancipation by Edna Greene Medford. Southern Illinois University Press, 2015. Cloth, ISBN: 978-0809333639. $24.95.

“Who freed the slaves?” is becoming a tiresome debate, but it remains contentious. Like most current interpretations, Edna Greene Medford’s Lincoln and Emancipation seeks a middle ground on the question. Relying on published primary sources, contemporary African-American newspapers, and on synthesizing secondary works on emancipation, Medford marshals an impressive array of voices and vignettes to succinctly demonstrate the codependence of Lincoln and African Americans in the emancipation process.

“Who freed the slaves?” is becoming a tiresome debate, but it remains contentious. Like most current interpretations, Edna Greene Medford’s Lincoln and Emancipation seeks a middle ground on the question. Relying on published primary sources, contemporary African-American newspapers, and on synthesizing secondary works on emancipation, Medford marshals an impressive array of voices and vignettes to succinctly demonstrate the codependence of Lincoln and African Americans in the emancipation process.

Medford is perfect for the task. Viewers of C-SPAN’s “American History TV” are familiar with the Howard University professor, a frequent and effective commentator on the network. Her interest in slavery began while growing up surrounded by antebellum planation homes and then as an undergrad at Hampton University—an institution with roots in Civil War contraband camps. Her graduate school career first took her to the state of Illinois, and there her interest broadened to include Lincoln. While her dissertation at the University of Maryland examined Virginia slavery, much of her subsequent career has focused on both slavery and Lincoln, particularly in her public history endeavors (she was on a panel of historians that shaped interpretations at the Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield, for example).

Medford’s Lincoln and Emancipation is a volume in Southern Illinois University Press’s “Concise Lincoln Library” series. In slightly more than one hundred pages, she provides an easy, jargon-free read that avoids long discourses on historiography (other than brief comments in her introduction). As with her public speaking, her writing style is smooth and highly accessible for the average history enthusiast.

Still, Medford’s work fits within larger historiographical debates. The North and Lincoln fought the Civil War for the sole purpose of restoring the Union, she argues, apparently rejecting the contention that from the start of the conflict mainstream Republicans saw it as a chance for emancipation. Yes, abolitionists and Radical Republicans saw it that way, as did the enslaved, but Medford shows Lincoln had no inclination to touch slavery in states where it already existed.

Medford veers from James Oakes’ Freedom National (2013) and more toward Gary Gallagher’s The Union War (2011) and especially Eric Foner’s The Fiery Trial (2010). She herself describes her work as a “traditional approach,” detailing the ideas and events that shaped Lincoln’s long hatred of slavery, but demonstrating his understanding that federal laws could not end it in the southern states. Instead, Lincoln believed that slavery would have to die more naturally, with slaveholders having a say in its demise. To accelerate a process he felt actually started with the Founders, Lincoln called for restricting the spread of slavery and then using the government to encourage compensated emancipation and the colonization of African Americans.

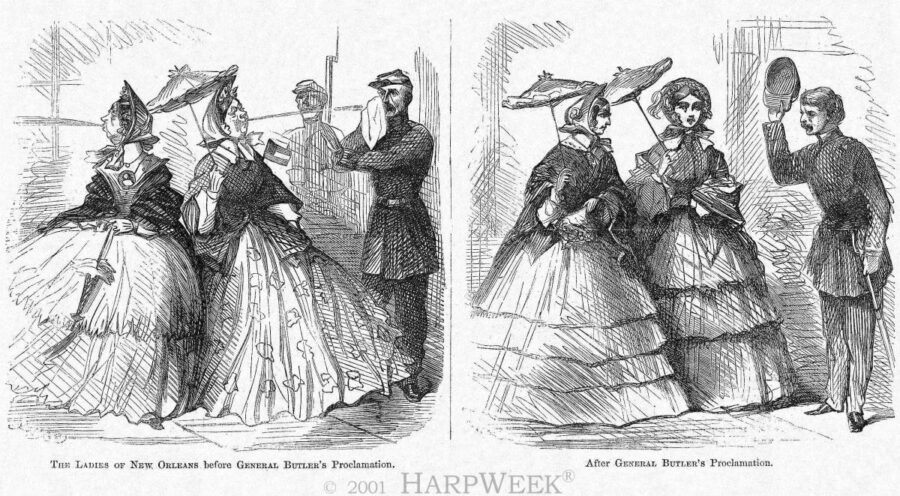

But the North’s military struggles in the war to save the Union changed all that. As failures mounted, Confederate nationalism grew, and it became increasingly evident that slavery was a Confederate strength. Medford argues that Lincoln was then willing to consider all options, including the use of presidential war powers to move against slavery (especially when the Border States vehemently rejected compensated emancipation). Issuing the Emancipation Proclamation was thus a military measure designed to take away a Confederate strength and add African American assistance to the Union cause.

To her credit, Medford avoids the trap of many of the Lincoln scholars by not glossing over or tortuously explaining away Lincoln’s continued embrace of colonization even after he decided on the Emancipation Proclamation. In fact, she paints the president as ultimately dropping the idea mainly because he needed African Americans to bolster Union troop strength. Saving the Union by winning the war trumped Lincoln’s embrace of colonization.

But Medford’s story is far from Lincoln’s alone. She convincingly demonstrates that African Americans were equal contributors to the emancipation process, and that neither Lincoln nor the slaves could have achieved their goals without the other. Medford sets this tone by beginning her work with the slave rebels Gabriel Prosser, Nat Turner, and Denmark Vesey. Black rebels and runaways resisted slavery in ways that increased the southern paranoia that played such a large role in creating sectionalism and secession. From the onset of the war for Union, blacks seized the moment for their own purposes. Free blacks tried to enlist to fight slaveholders, but also to prove they merited citizenship rights. Even as Lincoln eschewed a war of emancipation, slaves ran to federal lines, helping create a dilemma (along with radical Republicans) that led to the confiscation acts. Perhaps most important, courageous African American made real what Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation could only do in theory. For most of the enslaved, their actions alone could secure the freedom and military benefits promised by the decree. By spreading the word and fleeing to Union lines, African Americans gained their own freedom, deprived the South of their services, and weakened the Confederacy from within. Even the majority of slaves that were unwilling to risk the dangers of fleeing to distant Union lines (only to face horrific conditions in the contraband camps) contributed to the South’s demoralization by being insolent, stubborn, and refusing punishments.

Medford cogently explains the need for (and Lincoln’s championing of) the 13th Amendment that expanded and made permanent the freedom the proclamation and black actions had initiated. She also demonstrates that freed men and women held different ideas about their freedom than did Lincoln. They demanded citizenship, equality, and ownership of land. Many took the initiative to work lands vacated by their refugee masters and lobbied the president and local governments for the right to vote. The services of black troops (which Medford does a particularly effective job of succinctly detailing) led Lincoln to call for voting rights for certain African Americans, something largely unfathomable before the war. All these considerations ultimately paved the way for the 14th and 15th Amendments.

Medford’s epilogue briefly explores the black community’s contested memory of Lincoln (which became especially contentious after Reconstruction’s failures), from his death to Obama’s presidency. Her work thus ends by poignantly reminding us that both Lincoln and resilient African Americans made our first black president possible by turning the war for Union into one that also freed the slaves.

As Medford demonstrates, Lincoln was integral to emancipation, but so too were the African Americans who placed stresses on the institution of slavery well before him, made his decrees real and expanded their meaning, and continued the struggle beyond his death. Scholars will find Lincoln and Emancipation a useful synthesis with interesting vignettes involving a wide cast of characters, but this concise book will prove particularly effective in undergraduate courses. In it, Medford competently “restore[s] African Americans to their rightful place in the struggle for their own emancipation.”

Glenn David Brasher is a history instructor at the University of Alabama and the author of The Peninsula Campaign and the Necessity of Emancipation (2012), winner of the 2013 Wiley-Silver Prize from the Center for Civil War Research.