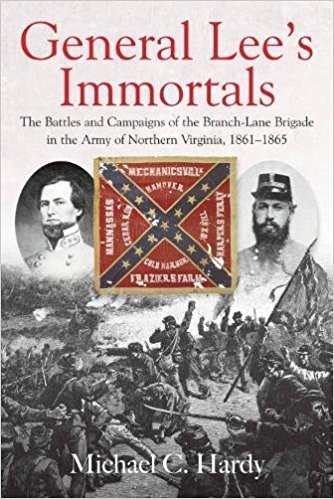

General Lee’s Immortals: The Battles and Campaigns of the Branch-Lane Brigade in the Army of Northern Virginia, 1861-1865 by Michael C. Hardy. Savas Beatie, 2018. Cloth, ISBN: 978-1611213621.$34.95.

Civil War history and historiography are replete with tales of legendary fighting units. While some units come immediately to the mind, others have faded into obscurity, remembered by only the most dedicated researchers and descendants. Michael C. Hardy, a prolific author and historian specialized in North Carolina’s Civil War history, brings one such outfit out of obscurity in General Lee’s Immortals, a detailed history of the Branch-Lane Brigade from the Tarheel State. Though regimental histories of various lengths have appeared over the years of the brigade’s respective regiments, Hardy’s work is the first history of the brigade itself.

Civil War history and historiography are replete with tales of legendary fighting units. While some units come immediately to the mind, others have faded into obscurity, remembered by only the most dedicated researchers and descendants. Michael C. Hardy, a prolific author and historian specialized in North Carolina’s Civil War history, brings one such outfit out of obscurity in General Lee’s Immortals, a detailed history of the Branch-Lane Brigade from the Tarheel State. Though regimental histories of various lengths have appeared over the years of the brigade’s respective regiments, Hardy’s work is the first history of the brigade itself.

From April 1862, the brigade consisted of North Carolina’s 7th, 18th, 28th, 33rd, and 37th infantry regiments. Hardy records that “the vast majority of these men were self-sufficient, non-slave owning yeomen farmers before the war,” representing 31 counties from the Tar Heel State “stretching from the mountains to the sea” (23). Lawrence O’Bryan Branch, an attorney, railroad president, and Democratic congressman, commanded the 33rdNorth Carolina before rising to brigade command. Troops under Branch’s command suffered frustrating defeats at New Bern, North Carolina, and Hanover Court House, Virginia, before proving their mettle in the Army of Northern Virginia’s campaigns under Robert E. Lee.

Branch’s brigade joined what became A. P. Hill’s famed Light Division, fighting their way down the Peninsula, then marching with Stonewall Jackson into northern Virginia. Branch’s Brigade executed a devasting counterattack at Cedar Mountain, helped hold the railroad cut at Second Manassas, and participated in the capture of Harpers Ferry. On September 17, 1862, the Tar Heels and the rest of Hill’s division made their famous breakneck march to rejoin Lee’s embattled army at Antietam. The North Carolinians arrived on the field in the very nick of time to save the collapsing Confederate right, but in so doing suffered the loss of Gen. Branch to a Union bullet.

James H. Lane, a VMI graduate and professor at the North Carolina Military Institute at the war’s outset, commanded the brigade for the remainder of the conflict. At Fredericksburg, the brigade took the brunt of an unexpected federal breakthrough on Jackson’s front. The following spring, Lane’s men were following Stonewall’s lead again, taking part in the legendary flank attack at Chancellorsville. It was also at Chancellorsville that the brigade earned its grimmest notoriety. The nervous pickets of the 18th North Carolina fired on Jackson and his staff as they rode through the dark woods, grievously wounding their corps commander. Ironically, one veteran claimed afterward that Jackson himself had warned the Tar Heels that, “the enemy was very near us and we must watch and listen and at the least noise, Fire, as it would be the foe” (198).

Following Jackson’s death from pneumonia, Lane’s Brigade arched north as part of Dorsey Pender’s Division, Hill’s Corps. July 2 saw Pender’s mortal wounding, so the North Carolinians would take part in Gettysburg’s great July 3 assault under Isaac Trimble’s command. The Tar Heels comprised the far left of the Confederate attack. Coming under terrible enfilade fire, the brigade was not able to advance much farther past the Emmitsburg Road. Lane’s Brigade saw yet more hard fighting throughout the Overland Campaign, breaking at the Wilderness under the onslaught of Hancock’s Second Corps but returning at Spotsylvania to launch their own stinging attack on the exposed left of Burnside’s Ninth Corps. The North Carolinians’ service continued into the trenches around Petersburg, even as the brigade and other formations lost men to the Confederates’ mounting problem of desertion. By Appomattox, fewer than 600 were present in the ranks for the surrender.

Hardy’s scrupulously researched chronicle of the Branch-Lane Brigade’s campaigns and battles would stand out on its own, but what truly sets apart his work from other unit histories are the thematic chapters detailing different aspects of soldier life. Hardy intersperses his narrative with chapters focusing on medical care, camp life, prisoners, and crime and punishment. What makes these chapters truly noteworthy is that they would serve as excellent introductions to these topics in Civil War soldier life for a broad range of readers, even as they are sourced entirely from the men of just five North Carolina regiments. Hardy’s work in the chapters on medicine and prisons is especially commendable. In many unit histories, men are lost to death, wounds, and capture, but almost by necessity the focus tends to fix on those men remaining to do the fighting. Hardy’s approach ensures that the stories of wounded men and prisoners do not disappear from the narrative.

General Lee’s Immortals has still more to commend. Hardy observes in his preface, “To understand the war in-depth, one must understand how a brigade worked in camp and in combat, how regiments were organized, and how the men reacted to battle, to being away from home, and to inter- and intra-unit politics” (vii). Weaving these subjects into his narrative, Michael Hardy demonstrates an in-depth knowledge of the inner workings of Civil War units, once again setting this book apart from a run-of-the-mill unit history. Additionally, the book is generously illustrated, including over 60 photographs of men from the brigade, detailed Hal Jespersen maps, and a number of period illustrations.

This is a book with much to offer a variety of audiences. Dedicated students of the Army of Northern Virginia, the Eastern Theater, and North Carolina’s role in the Civil War should consider it essential reading. Beyond those audiences, Michael Hardy’s considerable expertise ensures that this volume has something new to teach readers and scholars with a variety of interests. Combining rigorous research and an innovative organization, General Lee’s Immortals demonstrates what an exceptional unit history can teach us about the Civil War.

Jonathan M. Steplyk received his Ph.D. in History at Texas Christian University and is the author of the brand new Fighting Means Killing: Civil War Soldiers and the Nature of Combat.