Several months back, my friend Matthew Eng, coordinator at the Hampton Roads Navy Museum, asked me why the naval aspects of the Civil War tend to stand off from the main discussion of the war. When you think of the war’s great battles the likes of Gettysburg, Vicksburg, Antietam, and Chickamauga come to mind. Far down the list of most are Hampton Roads or Mobile Bay (and no small minority of readers are now reconnecting “Hampton Roads” with “Monitor” and “Virginia”). Indeed the naval history of the Civil War tends to be bolted onto the larger discussion just as the plating on those ironclad ships.

Yet, we would all agree that the naval aspects of the war are central to the discussion. The blockade was one of the cornerstones to northern strategy and defeating the blockade became a strategic objective of the Confederacy. Some of the most successful Federal campaigns of the war featured joint operations in which the land component depended on the Navy’s support. In terms of damage to the northern war effort, arguably the most cost-effective southern counter-strike was made by the high seas raiders. So why would we place such a divide between the land and naval aspects in our memory of the whole?

I think part of this divide stems from our physical links to the war. Today you can walk, thanks to a century of preservation, the great land battlefields. One may stand where great actions took place; stand in the footsteps of great leaders, considering their perspective; and even touch buildings and trees that stood at the time of the war. Rather hard to “walk” a naval battlefield (and those who can are less inclined to study military history). While there are a few surviving warships, most of those are guarded by “please don’t touch” signs. There are a large number of surviving cannons and other artifacts, but those sit out of context on static displays not at their wartime stations. Unlike the landward components of the war, today’s visitor has trouble “immersing” in the naval war.

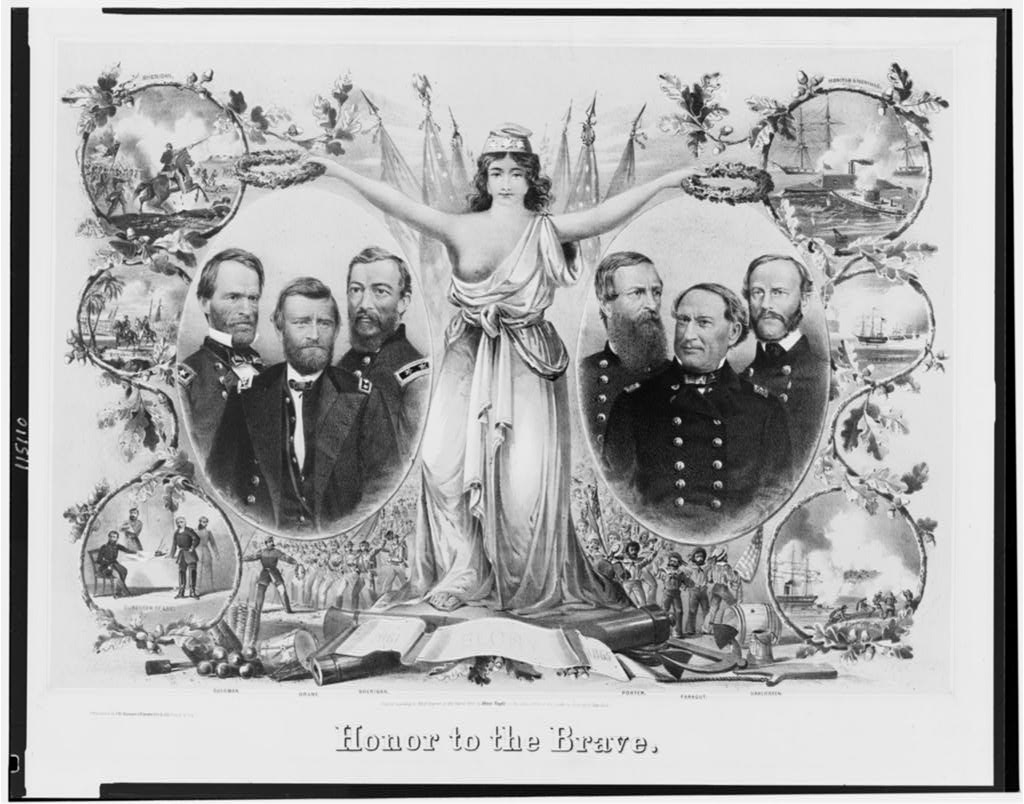

But more so the divide is a product of the collective memory handed down from the wartime generation. The imagery from the post-war period tends to focus on the Army’s battlefield leaders (example below).

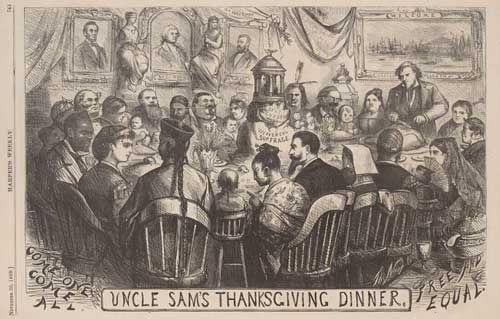

And where the Navy’s Captains and Admirals appear, they are often balanced against the landlubbers (example at the beginning of this post). To an extent, the preponderance of army slanted imagery is explained by the post-war political environment. After winning wars, Army generals have a habit of aspiring for political office.Navy admirals, we are told, just return to their ships.

Consider also the long shadow cast on our collective memory by the veterans’ organizations. These too were dominated by the army ranks. The nature of the recruiting and organization of Civil War armies reinforced this. Cities and counties sent regiments to fight in the armies. Naval recruiters drew from various ports to fill out a ship’s complement. Thus when the G.A.R., U.C.V., and other posts formed, they did so with ties to the locally raised companies and regiments that marched to war.

But ironically, as we look back the Army and Navy have approached the Civil War 150th differently. While both services are rightfully proud of their heritage, the Navy comes across more vocal in public venues, particularly using social media. At the First Manassas sesquicentennial events, interpretation experts from the Marine Corps museum narrated demonstrations on Henry Hill.

Perhaps this irony is explained in light of the evolution of each service over the span of 150 years. The army that fought the Civil War was different from the modern army in regards to origin, organization, and leadership. As one active duty officer related, “as a military professional, it is hard to relate to a commander whose pre-war job was painting houses,” referring to Federal General Thomas Devin. The men and women in the modern Navy, even while considering technology and time, might easily relate to the sailors of 1861-65 in those regards.

Regardless of the reasons, compared to the landward facets of the war, there are differences in the way we remember and approach the naval aspects of the war. Those differences often leave the Civil War Navy as a “bolted on” component to the whole study of the war.

Craig Swain is a consultant from Virginia but is a native Missourian. His background includes a degree in history and service in the Army. Craig’s focus is the study of Civil War Artillery, which you can read about on his blog To the Sound of the Guns.

Photo Credits: Kimmel & Forster lithograph (courtesy of Encore Editions) and the Library of Congress.