In the Voices section of the Summer 2021 issue of The Civil War Monitor we highlighted quotes by Union and Confederate soldiers about fear. Unfortunately, we didn’t have room to include all that we found. Below are those that just missed the cut.

“When we got to the brow of the hill the column, which had been marching by fours, halted to wheel into companies. Company C had the right and as I stood by the colonel I was close to Captain Jordan, who had the reputation of being one of the bravest officers in the regiment. I watched him with curiosity to see how this approach to danger affected him. To my astonishment he was digging his nails into the palms of his hands, and his lips were white under his clenched teeth. Then I knew that he was more scared than I was; and I realized that he ought to be, for he had more at stake. If my poor little candle were snuffed out nobody would notice that it had grown any darker, but he was a husband and a father.”

—Charles William Bardeen, a fifer in the 1st Massachusetts Infantry, on a scene during the Battle of Fredericksburg, in his memoirs

“I remained perfectly still, and in a few minutes I saw a young Yankee lieutenant peering through the bushes. I would rather not have killed him, but I was afraid to fire and afraid to run, and yet I did not wish to kill him. He was as pretty as a woman, and somehow I thought I had met him before. Our eyes met. He stood like a statue. He gazed at me with a kind of scared expression. I still did not want to kill him, and am sorry to-day that I did, for I believe I could have captured him, but I fired, and saw the blood spurt all over his face. He was the prettiest youth I ever saw. When I fired, the Yankees broke and run, and I went up to the boy I had killed, and the blood was gushing out of his mouth. I was sorry.”

—Samuel R. Watkins, 1st Tennessee Infantry, on an incident during the fight for Atlanta, in his memoirs

“A hundred yards before we got to the hill we ran into a strong line of rifle pits swarming with Johnnies. They caved and commenced begging. The pit I came to had about 20 in it. They were scared until some of them were blue, and if you ever heard begging for life it was then.”

—Illinois soldier Charles W. Wills, on fighting in the Atlanta Campaign, in his diary, June 15, 1864

“By this time the soldiers became aware of his presence and its object. In a brief moment a fierce commotion was raging. The slave owner did not search a single tent; but was hooted and driven out of camp in hot haste. The last seen of him, with all of his boasted bravery oozing out at his finger ends, white as a sheet and trembling, like the coward that he was, he was running for dear life to escape the threatened hanging he so well deserved and feared he would get. Even after he was safely away from our lines, it is said that he was still so badly scared that he traded his high-toned coat and hat with a poorly dressed negro he met upon the road so as to be in disguise if by chance any Union soldier should meet him. He never again returned to our camp.”

—Albert O’Connell Marshall, 33rd Illinois Infantry, on the visit of a “slave catcher” to their camp near Jacksonport, Arkansas, in search of an escaped enslaved man, in his journal, May 1862

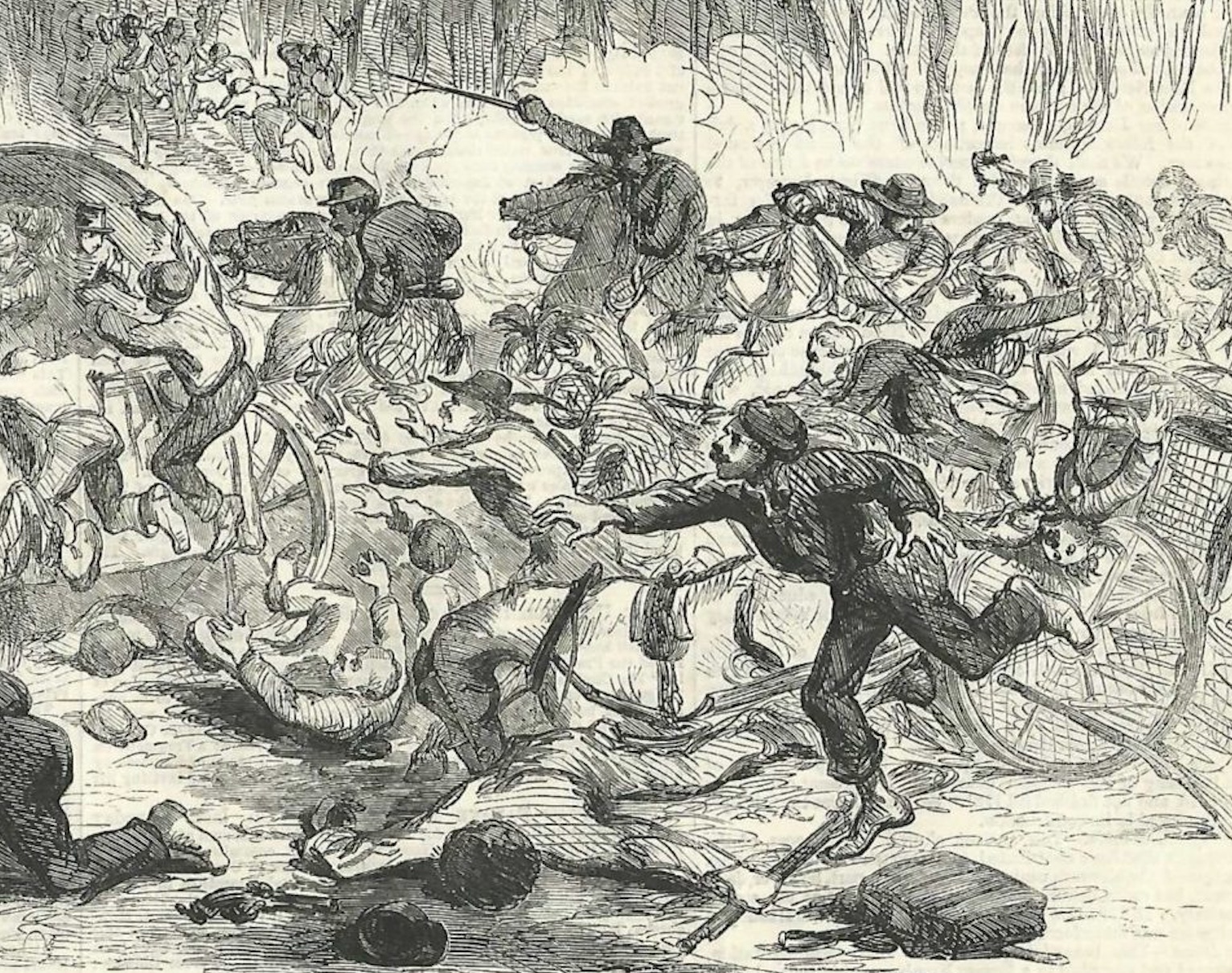

The panicked Union retreat during the Battle of Bull Run

“Near us was a man crouching behind a small disintegrated stone, which was about the size of a common water-bucket. He was bent up, with his face to the ground, in the attitude of a pagan worshipper before his idol. It looked so absurd to see him thus, that I went and said to him: ‘Do not lie there like a toad, —why not go to your regiment and be a man?’ He turned up his face with a stupid, terrified look upon me, and then without a word turned his nose again to the ground. An orderly that was with me at the time told me a few moments later, that a shot struck the stone, smashing it in a thousand fragments, but did not touch the man, though his head was not six inches from the stone.”

—Wisconsin officer Franklin A. Haskell, on an incident during the Battle of Gettysburg, in his memoirs

“Hot firing opened at daybreak, and it seemed so near that when orders came to ‘fall in line,’ the new German recruits simply would not obey. They were so terrified that they lay like logs, and no amount of rough handling, even with bayonets, had any effect upon them whatever. The order to advance was given; still these fellows clung to the ground with faces buried in the grass, and, although some were shot by the officers, literally nothing moved them.”

—Union surgeon John Gardner Perry, on an incident he witnessed during the opening of the Overland Campaign, in a letter home, May 3, 1864

“The boats were rapidly nearing the lower batteries, and the shells were beginning to fly unpleasantly near. My heart beat quickly as the flashes of light from the portholes seemed facing us. Some of the gentlemen urged the ladies to go down into the cave at the back of the house…. While I hesitated, fearing to remain, yet wishing still to witness the termination of the engagement, a shell exploded near the side of the house. Fear instantly decided me, and I ran, guided by one of the ladies, who pointed down the steep slope of the hill, and left me to run back for a shawl. While I was considering the best way of descending the hill, another shell exploded near the foot, and, ceasing to hesitate, I flew down, half sliding and running. Before I had reached the mouth of the cave, two more exploded on the side of the hill near me. Breathless and terrified, I found the entrance and ran in, having left one of my slippers on the hillside.”

—Vicksburg resident Mary Ann Webster Loughborough, on a scene from the Union siege of the city, in her memoirs

Horace Porter

“In ascending a Southern river on a steamboat, … we had an officer on board who, during three years of fighting, had treated shot and shell in action with an indifference that made him a marvel of courage; but on this expedition he manifested a singular fear of torpedoes, put on enough life-preservers to float an anchor, and stood at the stern of the boat ready, at the first sign of danger, to plunge into the water with the promptness of a Baptist convert.”

—Lieutenant Colonel Horace Porter, aide-de-camp to Ulysses S. Grant, in a postwar article on the conflict

“[A]fter the first group of soldiers appeared running out of the woods, the plain was swarming with them, flying with all speed, and in such bodies and so blindly terrified that neither natural obstacles nor the well-ordered array of lines arrested their flight; and some, escaping through the south front, actually ran clear to our skirmish line and through it to or toward the enemy on the south.”

—New Hampshire officer Thomas Leonard Livermore, on the breaking of the Union lines during the Battle of Chancellorsville, in his memoirs

“Panic and terrorism are doing their worst here, and they are terrible agencies in such times as these.”

—Wilder Dwight, 2nd Massachusetts Infantry, on the state of the army in the wake of the Battle of Bull Run, in a letter to his brother, July 26, 1861

“[W]e were going ahead at a regular pace, when, just as we made the crest of the rise beyond the stream, there burst upon our view the appalling spectacle of a panic-stricken army—hundreds of slightly wounded men, throngs of others unhurt but utterly demoralized, and baggage-wagons by the score, all pressing to the rear in hopeless confusion, telling only too plainly that a disaster had occurred at the front. On accosting some of the fugitives, they assured me that the army was broken up, in full retreat, and that all was lost; all this with a manner true to that peculiar indifference that takes possession of panic-stricken men. I was greatly disturbed by the sight….”

—Union general Philip H. Sheridan on an encounter during the Battle of Cedar Creek, in his memoirs