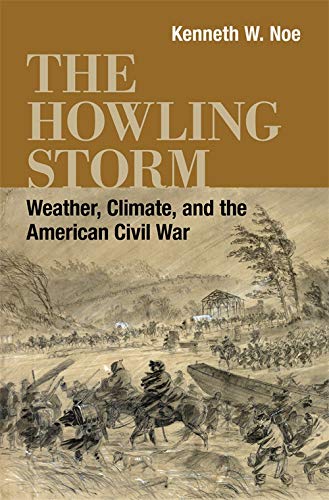

Union soldiers bask in the sweltering summer sun in camp

In the Voices section of the Summer 2015 issue of The Civil War Monitor we highlighted first-person quotes from Union and Confederate soldiers about the intense heat and discomfort that accompanied summer campaigning. Unfortunately, we didn’t have room to include all that we found. Below are those that didn’t make the cut.

“Since the 2nd we have lain in the rifle-pits with the infantry, sweltering in the sun in the day time and doing quite our share of picket duty at night. The dust, fine as ashes, is at least four inches deep in the trails and covered ways used by the troops, and at midday it is no uncommon thing to see the thermometer mark 110 degrees in what little shade there is. There has been no rain for weeks, and heat is killing more men than the ‘Johnnies’ are.”

—Captain Augustus Cleveland Brown, 4th New York Heavy Artillery, in his diary while on campaign in Virginia, July 11, 1864

“This awfully hot Sunday morning I am going to try to write a letter home. We have been sweltering in this hot Virginia sun with the thermometer at 102 in the shade now for three days. It seems as if the perspiration runs in streams all the time and brings no relief.”

—Mason Whiting Tyler, 37th Massachusetts Infantry, in a letter to his mother during the early days of the siege of Petersburg, Virginia, June 26, 1864

“The men fought well, however, though half dead with heat, thirst, and weariness. Some broke for the river and plunged in the cool water for an instant, then emerging, rushed back to the fray and fought like lions.”

—Union surgeon Thomas Ellis, on the Battle of White Oak Swamp, Virginia, June 1862, in his diary

“Back we came, therefore, dragging wearily into our old camp through all the dust and heat, tired in every bone, every fibre of clothing soaked and resoaked in perspiration; having, in the course of four days, gone some fifty or sixty miles. We hope it was our last march. God send it may be so! for it is too much for men.”

—Corporal James Hosmer, 52nd Massachusetts Infantry, on a recent march to Clinton, Mississippi, and back in search of Confederate forces, in his diary, June 11, 1863

Union staff officer Theodore Lyman

“I can only say that I have ‘sweltered’ to-day—that is the word; not only has it been remarkably broiling, but this region is so beclouded with dust and smoke of burning forests, and so unrelieved by any green grass, or water, that the heat is doubled. We have had no drop of rain for twenty days, and but a stray shower for over a month.”

—Union staff officer Theodore Lyman to his wife, June 25, 1864

“[W]e were out on picket, when the order came to march; we got into camp at one o’clock, and at six in the morning we were all ready to move. We marched twenty-two miles this day; it was terrible hot and dusty, and during one of the halts we shot a man for desertion…. Next day marched thirteen miles…. On the next day, … twenty-one miles, weather still very hot. Monday marched to Centreville, distance seven miles. Lay there the remainder of the day, and also the following day. On Wednesday we marched to within three miles of this place; the distance was about fourteen miles. Quite a number of our poor fellows, while on the march, fell dead in the road, being overcome from the excessive heat and dust.”

—Massachusetts infantryman Warren Hapgood Freeman, in a letter written to his father near White Oak Church, Virginia, June 7, 1863

“[B]eing attached to the hospital, … I had to follow the hospital wagons, look after the stores, and attend the sick and wounded in the ambulances. These wagons took the same route as the troops but kept far in their rear. The heat each day was intense, and the dust beyond any expression of which I am capable; but suffice it to say that most of the time I could not even see the head of my horse. The whole train was fifty miles long, the roads sandy, and we moved with the heavy draw of great bodies. We marched about sixty miles in four days and nights, halting every six or eight hours to bait horse and man.”

—Union surgeon John Gardner Perry, in a letter written near Petersburg, Virginia, June 21, 1864

“Another day still finds us marching in dust and under a scorching sun. The heat has indeed been intense. Many a poor soldier has fallen out on the way from exhaustion and sunstroke.”

—Captain Lemuel Abbott, 10th Vermont Infantry, in his diary while on march in Virginia, August 12, 1864

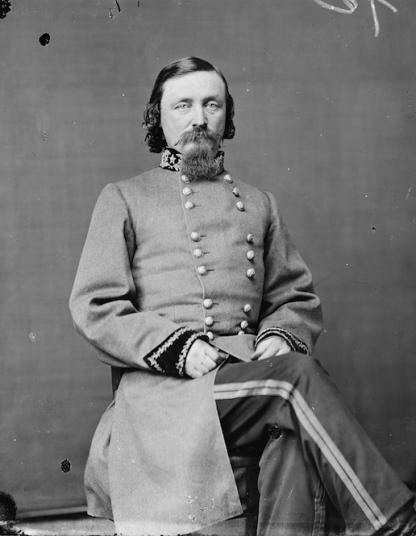

“The men are lying in the rear, my darling, and the hot July sun pours its scorching rays almost vertically down upon them. The suffering and waiting are almost unbearable.”

—Confederate general George E. Pickett, in a letter to his wife as his men awaited the order to advance on July 3, 1863, at Gettysburg

“We still lie here waiting for the fall of Vicksburg, and expect it will be ours in from ten days to two weeks from this. Grant’s fine army needs a few weeks of rest very much. Marching and countermarching, fighting, watching, and digging, with hot weather, dry and excessively dusty roads and fields, miserable camping-places on the ground, and great scarcity of water—and what we dig for is unhealthy, with very great excess of noxious chemical compounds—short diet, sleepless nights, dirty clothes, absence of tents, distance of wagons, and much confusion among these countless hills, all have aided in rendering the troops debilitated, and most decidedly uncomfortable.”

—H.H. Penniman, 17th Illinois Infantry, in a letter to his wife, June 6, 1863

“Hot dusty marching. Much suffering from the extreme heat. Every time we halt, run for water. Many good springs in this section. Once in a while we find a sulphur spring. Don’t like the taste of it but are obliged to drink it in order to quench our thirst. I am in the best of health. Rugged enough for this kind of life.”

—Charles H. Lynch, 18th Connecticut Infantry, in his diary while on campaign in Virginia, May 9, 1864

“Drought all over the country—blazing heat all around, no ice water to cool our parching tongues. Water in the wells hard to get—that in the creeks unfit to drink, being almost warm enough to boil an egg. It was too hot for military training. There was however, company drill and dress parade.”

—John C. Myers, 192nd Pennsylvania Infantry, in camp at Baltimore, Maryland, July 29, 1864