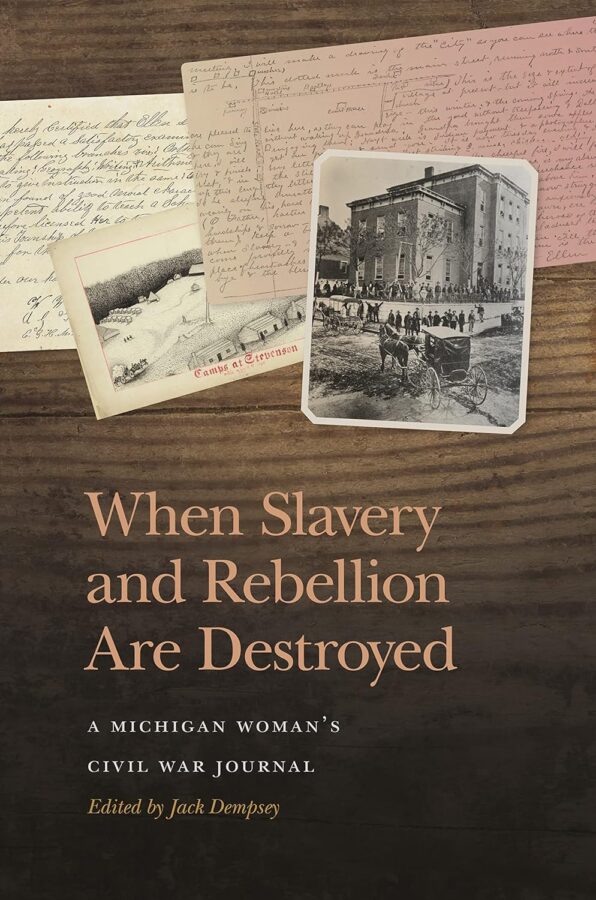

When Slavery and Rebellion Are Destroyed: A Michigan Woman’s Civil War Journal edited by Jack Dempsey. University of Georgia Press, 2023. Paper, ISBN: 9780820365602. $24.95.

Worry and anxiety. As historians in recent years have turned their attention to the role of emotions in both the leadup to the Civil War and the war itself, reading the family letters of the era as expressions of feeling enhances understanding of the war’s impact on ordinary people. It is hardly surprising that the correspondence between Ellen Preston Woodworth and her soldier husband Samuel often dwells on worrisome moments or pervasive anxieties. The very fact that Ellen would later painstakingly copy their correspondence into a journal signifies how much the emotions surrounding the trials of separation resonated long after the war.

Then too, various and conflicting emotions were strongly tied to Ellen and Samuel’s wartime experiences—and occasionally to broader issues. The Woodworths owned a plot of 160 acres, land most recently occupied by the Ojibwe people, and so had some exposure to Native American society and culture. Ellen’s letters offer a detailed picture of an active woman’s busy life in a rural area of central Michigan. By the spring of 1864, she has started teaching school, and her letters describe how she cared for herself and her two sons on the assumption that Samuel might not be able to offer much help—or might not come home. Samuel’s letters recount military service detached from the war’s bloodiest engagements and often focus on health problems.

The roller coaster of emotions ran both directions. A carpenter by trade, and facing the prospect of being drafted, in September 1863, Samuel joined the 1st Michigan Engineers. His wartime service largely consisted of guarding supply routes in northern Alabama and Tennessee while building blockhouses. Aside from construction dangers and occasional attacks by “bushwhackers,” for Samuel and his comrades (as for so many soldiers), the deadliest enemy was disease. His letters chronicle a series of health problems, most notably chronic diarrhea; in one twelve-week stretch, his weight fell from 157 to 112 pounds. Ellen did not approve of Samuel’s enlistment but thought he made a good-looking soldier. “We are left so lonely—so entirely unprotected,” she complained, and confessed to having little patriotism (28). But from the outset she gained confidence managing affairs at home, including both crops and children. Ellen was deeply religious, finally joined the Methodist church, and worried about Samuel’s spiritual welfare. She says relatively little about the course of the war. More often, the letters record daily activities along with visits, meetings, and the doings of a rural community. She seems satisfied teaching school but shows more enthusiasm for church activities. Hoping for her husband’s eventual return, she envisions building a nice house on a farm. Had she been a man, she would have voted for Abraham Lincoln’s reelection and alludes to the possibility of an appointment as a postmistress.

Samuel’s much briefer letters nevertheless display great interest in home affairs with frequent inquiries about his sons and occasional admonitions about their behavior. Like many soldiers, he assures his wife that he will not pick up bad habits in camp; he will especially shun swearing and cardplaying. The letters trace Samuel’s deepening religious faith; he expresses regret over his wayward life and opposition to Methodism. He worries about being taken prisoner or being sent to a hospital. In October 1864, Samuel notes how he has learned much about the “horrid institution of Slavery” from conservations with the enslaved. He finally decides that he has become an “abolishionist.” (145-146). By Samuel’s reckoning, two-thirds of the men in his outfit support Lincoln’s reelection. As the war is winding down after the presidential election, he suffers greatly from leg sores and is sent to a hospital in Nashville from which he is discharged from the army in May 1865.

Jack Dempsey has ably edited Ellen’s journal of letters. A solid introduction and helpful notes (both grounded in current scholarship) make the collection quite accessible. The volume includes a brief appendix of postwar writings describing Samuel’s decision to enlist and telling of Ellen life as a “plucky woman.” Less a window on the war and more the story of an ordinary family, When Slavery and Rebellion Are Destroyed is nevertheless worthwhile for general readers and scholars alike.

George C. Rable is Professor of History Emeritus at the University of Alabama. His latest book is Conflict of Command: George McClellan, Abraham Lincoln, and the Politics of War.