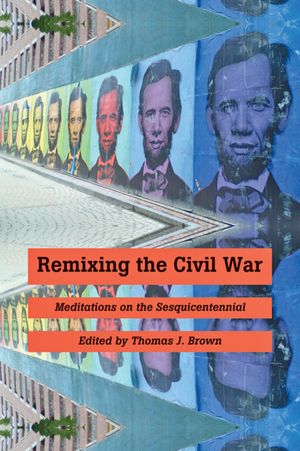

Remixing the Civil War: Meditations on the Sesquicentennial edited by Thomas J. Brown. The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011. Cloth, ISBN: 1421402505. $50.00.

Who could have anticipated that, by the early years of the twenty first century, America’s bloodiest military conflict might be re-imagined in the form of a photograph of nine smiling Lincoln impersonators, appropriately titled “Nine Lincolns?” Or by a performance artist, dressed as a Civil War era soldier sitting astride a monumental “hobby horse,” singing a song set to the tune of “When Johnny Comes Marching Home?” These are some of the Civil War “remixes” considered in this exceptionally thoughtful and wide-ranging volume of essays, all concerned with ongoing, and often unusual, reflections on the Civil War in our current moment of the war’s 150th anniversary. Touching on such diverse subjects as Barack Obama’s very recent deployment of the Lincoln image, current controversies over the Confederate battle flag, and contemporary black artists’ interpretations of the war, most of the essays in Remixing the Civil War offer rich analytical insights on how and why the Civil War continues to provide a critical touchstone for so many Americans in so many different genres.

Who could have anticipated that, by the early years of the twenty first century, America’s bloodiest military conflict might be re-imagined in the form of a photograph of nine smiling Lincoln impersonators, appropriately titled “Nine Lincolns?” Or by a performance artist, dressed as a Civil War era soldier sitting astride a monumental “hobby horse,” singing a song set to the tune of “When Johnny Comes Marching Home?” These are some of the Civil War “remixes” considered in this exceptionally thoughtful and wide-ranging volume of essays, all concerned with ongoing, and often unusual, reflections on the Civil War in our current moment of the war’s 150th anniversary. Touching on such diverse subjects as Barack Obama’s very recent deployment of the Lincoln image, current controversies over the Confederate battle flag, and contemporary black artists’ interpretations of the war, most of the essays in Remixing the Civil War offer rich analytical insights on how and why the Civil War continues to provide a critical touchstone for so many Americans in so many different genres.

In his introduction, editor Thomas Brown conveys one of the volume’s most critical insights: that today’s Civil War provides less of a history lesson and more of a means for meditating on a wide range of current concerns, everything from the cult of celebrity to militarism and homosexuality. And, as the best essays in this collection suggest, we cannot help but look at the Civil War today through the lens of the 150 years that has transpired since its conclusion. Our most recent historical reference points—the Civil Rights Movement, the struggle for gay rights, recent wars in Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan—reverberate in our modern-day Civil War.

In the volume’s first essay, C. Wyatt Evans considers the frequent parallels made, in 2008, between then presidential candidate Barack Obama and the nation’s sixteenth president. Beyond simply surveying the numerous Lincoln references, Evans, to his credit, forces us to think historically about these recent events, particularly how the Democratic Party managed, in an unusual strategic turn, to usurp the Republicans in claiming and shaping a historical narrative. Likewise, in a deeply contextualized essay on the struggles over the Confederate battle flag in South Carolina, Thomas Brown considers how much the current proponents of the flag have departed from the ideas and the tactics of their earlier forbears. The muscular, NASCAR-loving tendencies of current Confederate flag-wavers, he notes, have little in common with the elitist overtones of the older ladies’ memorial associations. Moreover, says Brown, today’s opponents of the flag see not so much the shadow of slavery but a more recent image of the Klan in the 1950s and 1960s. Indeed, so strongly do these Civil Rights era memories resonate that some black leaders have even been willing to accept displays of the Confederacy’s first national flag, a banner that has no historical associations with recent racial strife.

Nor is it possible to think about the Civil War in 2012 without the extended history of commercial exploitation that has surrounded the conflict. The artist Allison Smith, for example, discussed in an essay by Gerard Brown, has envisioned the Civil War in terms of the “hobby horse” described above, thoroughly entwined with American culture’s attachment to kitsch and nostalgia. Numerous artists, too, recognize how much popular culture icons—like D.W. Griffith’s “The Birth of a Nation” and the book and film versions of Gone with the Wind—have shaped the way we think about the Civil War today.

The Civil War, perhaps not surprisingly, has emerged with a particular resonance for African American writers, artists and film-makers, as well as for the black community at large. Mitch Kachun makes some interesting observations about current commemorations of emancipation, finding a decided preference among African Americans for the more grassroots-based “Juneteenth” celebrations. Yet, Kachun’s somewhat narrow focus on official commemoration days steers him away from broader questions about how, or even if, black Americans today reflect on slavery and emancipation, and how much the content of their historical memories has been shaped by events of the 1960s—and later—more than the 1860s. Robert Brinkmeyer, too, misses an opportunity to reflect more deeply on the recent political and historical concerns that have influenced black writers—like Toni Morrison and Alice Randall—in their Civil War-themed writings. Fitzhugh Brundage, however, makes up for some of these oversights in a very thoughtful essay on African American artists—including the visual artist Kara Walker, the playwright Suzan-Lori Parks, and the remix artist DJ Spooky—who interpret the Civil War, as Brundage explains, in a “post-soul age.” In upending traditional and iconic cultural forms—like the old-timey silhouettes constructed by Walker or DJ Spooky’s destabilized remix of “Birth of a Nation” – these artists point to the hollowness in the dominant popular culture and how it has been complicit in erasing a history of racial violence. Yet Brundage, perhaps unfairly, also criticizes these artists for failing to move beyond their call for revision. Where, he asks, are the suggestions of black agency that might be at the heart of a revised historical narrative? No doubt this is an important question, but perhaps not a realistic objective for these artists given their aesthetic parameters.

In his afterword, art historian Kirk Savage suggests ways in which reflections on the war today might surmount the racial and other divides that continue to shape the way we encounter the sectional conflict of the nineteenth century. He advises blending our discussion of the 50th anniversary of Civil Rights events with the Civil War. And he calls for placing the Civil War in a broader context that would link US developments to world-wide struggles between (usually white) settlers and native inhabitants. These are admirable suggestions, certainly not to be dismissed by scholars, public historians, and others interested in the Civil War anniversary. Yet, they also strike a discordant note of optimism, coming at the end of a volume that has reminded us how much the Civil War has been trapped by contentious politics, mired in insidious commercialism, and left floundering on the shores of racial antagonism.

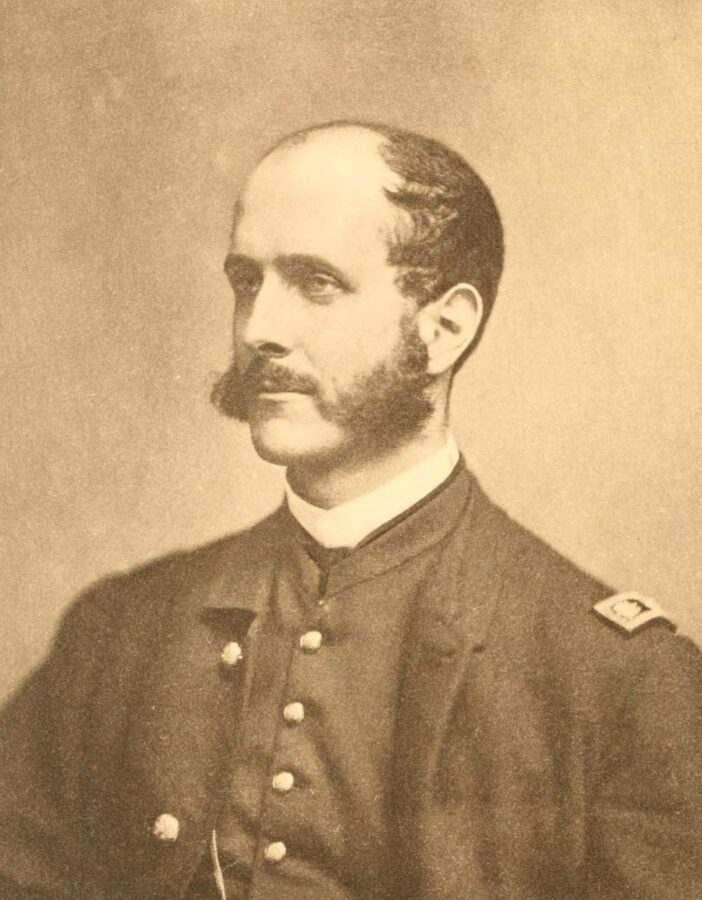

Nina Silber is a Professor of History at Boston University and the author of numerous books about the Civil War, including The Romance of Reunion: Northerners and the South, 1865-1900.