Discussions surrounding Bowdoin College and the Civil War invariably return to the famous Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain of the 20th Maine and the acts of his regiment at Gettysburg on July 2, 1863. Indeed, the actions of Chamberlain and his men have become synonymous with victory for Union forces on the battle’s second day—never mind the important role of some New Yorkers on Little Round Top and Culp’s Hill. The relationship between Joshua Chamberlain and his brother Tom has been well documented in popular and scholarly assessments of Maine’s best-known general. One might be led to believe that there was only a single pair of brothers from the state of Maine with ties to Bowdoin College that rose to prominence during the War—with the eldest brother achieving the greatest notoriety. However, another brotherly duo at Bowdoin is even more important to our understanding of the War: Oliver Otis and Charles Howard.

To be sure, the name Oliver Otis Howard is not completely unknown in Civil War circles. “Uh Oh” Howard’s actions at Chancellorsville on May 2, 1863, are perhaps what he is regrettably best known for. The quick work made of Howard’s XI Corps at Chancellorsville by Stonewall Jackson’s flank march has become instrumental to the narrative of one of Robert E. Lee’s greatest victories. Yet the work of O.O. Howard and his brother Charles illuminate some of the greatest challenges of the Wwar and the postwar efforts to reconstruct a devastated South. Otis (as his family referred to him) and Charles hailed from the small town of Leeds, Maine, and attended Bowdoin in the 1850s—Otis graduating in 1850 and Charles in 1859. Otis continued his education at West Point graduating in 1854 and ultimately returned to the academy as an instructor several years later. The two brothers lived together at West Point during the 1859-1860 academic year and witnessed some of the final sectional rifts that ultimately tore the nation asunder. Otis received a colonel’s commission in the volunteer army at the onset of hostilities and Charles quickly joined him in the field—a partnership that lasted for the better part of the war. By spring 1862, Otis commanded a brigade and Charles, a lieutenant, acted as one his aides. The first part of the war for the Howard brothers brought questions regarding the status of slaves as they entered Union lines and it is indeed remarkable to see the evolution of the two brothers’ ideology when it came to slavery as the war progressed—an evolution that dramatically affected their post-war careers.1

At the battle of Fair Oaks on June 1, 1862, both brothers fell wounded—Charles in the leg shortly after his brother was hit in the arm. Otis’ wound would require the amputation of his right arm. For Charles, a painful rehabilitation awaited and lasted until days before the battle of Antietam, where the brothers would again face a torrential fire in the West Woods but escape unharmed. A minor wound for Charles at Fredericksburg capped a remarkable year for the Howard brothers, but provided just a glimpse at the hell that awaited them in May 1863.

Chancellorsville serves as the most recognizable moment of O.O. Howard’s Civil War career for the shellacking that his XI Corps experienced at the expense of Stonewall Jackson’s men. However, a closer examination of the evidence may yield a call for a long-overdue reassessment of Howard’s role at Chancellorsville. For starters, Howard insists that he never received orders from Joseph Hooker indicating a threat upon the flank of the army and Otis truly believed that his men were in the best position they could be, given the ground. Criticism following the battle from the likes of Carl Schurz cannot be taken seriously because of Schurz’s own aspirations to command the corps himself. Howard had too much faith in his subordinate commanders and for that we can certainly find him at fault. Perhaps he could have done more in preparation for an assault on his flank, but those who have walked the ground know that is far easier said then done. However, I am wary of those who judge Howard on his performance during the first hours of the assault on May 2 alone. The work of Otis and his brother Charles as they tried to shore up the XI Corps line was remarkable and often overlooked because of the brilliant strategy and execution by Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson and the subsequent wounding of Jackson towards the end of the battle.

Howard often faces further criticism for his actions at Gettysburg, but the line that his corps was forced to cover and hold against superior Confederate numbers on July 1 could not have been held for a significant period of time; indeed, I find that Howard did remarkably well at Gettysburg given the circumstances. The loss of men who were captured in the streets of Gettysburg made things appear far worse. For the next two days, the corps fought admirably against Confederate assaults on Cemetery and Culp’s Hill (the former of which Howard made sure soldiers occupied even before the I and XI Corps fell back through town.) The fall of 1863 witnessed the transfer of the XI Corps to the Western Theater and of O.O. Howard largely into obscurity, but I would contend that we should look at the Howard brothers and their actions in the west to garner a greater appreciation of their actions during the entire Civil War.

Upon his arrival in the west, O.O. Howard remarked, “I feel that I was sent out here for some wise and good purpose.” Where Otis met with trouble in the east, he truly excelled in the west under a strong partnership with William Tecumseh Sherman. Sherman heaped high praise on Howard following the battle of Chattanooga, remarking how astounded he was with “one who mingled so gracefully and perfectly the polished Christian Gentleman and the prompt, zealous, and gallant soldier.” The partnership continued to succeed as Sherman marched his men toward Atlanta with Sherman grateful for Howard’s actions and leadership at Resaca and Ezra Church. Howard’s rise to army command following the death of General James B. McPherson at the battle of Atlanta in July 1864 put more responsibility on Otis for the subsequent March to the Sea, but it was a task he undertook with great poise and precision.2

The Western Theater also brought with it great advancement for Charles Howard. Rising to the rank of major, Charles served as his brother’s adjutant while also undertaking an important mission for Sherman to Vicksburg and New Orleans. Indeed, Sherman came to trust and respect Charles Howard to such a degree that Sherman selected Charles to personally debrief the president regarding the March to the Sea. Charles had remarked that there were many men waiting to meet with the president once he arrived at the White House, but upon hearing the nature of Charles’s business, Lincoln ushered him to the front of the line. Lincoln was so anxious to hear of the progress made by Sherman that he interrupted his shaving to speak with Howard. The following account by Charles in Otis McGraw Howard’s biography of his father provides a wonderful story of a president who was so curious as to Sherman’s movements, but also of a commander in chief beset by “intense sadness of his great deepset eyes” and surrounded by an “air of weariness and responsibility.” According to Otis McGraw Howard, his father recalled:

“I remember how he towered above me in height and how this unusual tallness impressed me then as never before, though I had already met him twice when he at different times visited the Army of the Potomac. He sat beside me on the sofa and put me quite at my ease by his generous words of Sherman and his army and his especially kind mention of my immediate commander. Then followed a most informal talk as to how he himself and the country had evidently been more anxious about Sherman’s army than they were for themselves and questions as to the difficulties and experiences of the march and how they were met. The solicitude and thoughtful interest expressed seemed to be of that personal and heartfelt kind that a father might feel for his own sons, rather than those of the official head of the Government for the officers and soldiers subject to his authority.”3

Charles’ venture to Washington also brought with it a promotion to the colonelcy of his very own United States Colored Troop (U.S.C.T.) regiment. The 128th U.S.C.T. would only form up in the last days of the war but carried on into the early periods of Reconstruction. Charles would miss the bulk of the Carolina Campaign but joined his brother in the waning days of the war prior to the surrender of Joseph Johnston’s forces. With Johnston’s surrender, the war was over for the Howard brothers, but the battle to win rights and educational opportunities for the four million freedmen in the South was just beginning. Otis Howard would lead the Freedmen’s Bureau and Charles went on to serve in a variety of capacities for the Bureau throughout the South during Reconstruction. The two brothers could count among their achievements vast improvements in educational opportunities for the freedmen considering what little fiscal resources were at their disposal.

Otis continued to serve in the army until his retirement in 1894 while Charles would enter the world of publishing following his service. Charles would die in 1908 with his older brother Otis succumbing to illness in 1909. These two provide a glimpse of another pair of Maine brothers with ties to Bowdoin who served their country during some of its darkest days. While they may not have been on Little Round Top that July afternoon, or received the Confederate surrender at Appomattox Court House, they nevertheless played a significant role in the Union Army’s push in the Western Theater. Additionally, they promoted policies in keeping with the wishes of the late President Lincoln to provide greater opportunity to the recently freed slaves of the South. For many, O.O. Howard will be the blundering fool of Chancellorsville and nothing else. Perhaps, however, as we commemorate the sesquicentennial of the War and reassess the roles of its lesser-known participants, some will begin to see the greater complexities that lie behind this man and a brotherly bond that transcended a war and the struggles and perils of Reconstruction.

David K. Thomson is a doctoral student at the University of Georgia and a contributing editor for The Civil War Monitor. He is the editor of the forthcoming work “We Are in His Hands Whether We Live or Die”: The Letters of Brevet Brigadier General Charles Henry Howard (University of Tennessee Press, 2013.)

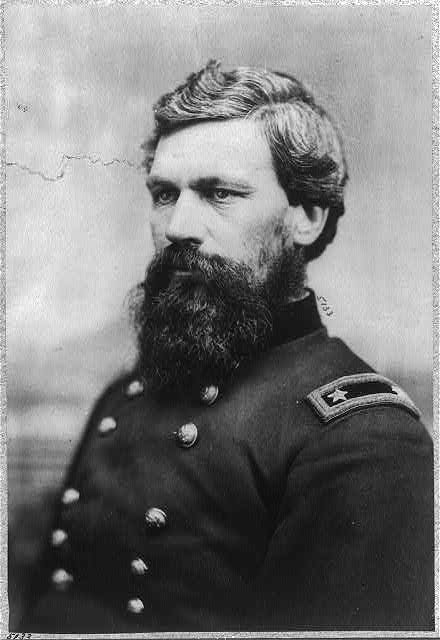

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division: www.loc.gov.

1For more information on the Howard brothers and the issue of contraband, see Charles Henry Howard to Eliza Gilmore, August 12, 1861, and Charles Henry Howard to Rodelphus Gilmore, January 13, 1862, both in Charles Henry Howard Papers, George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections and Archives, Bowdoin College Library.

2Oliver Otis Howard to Lizzie Howard, October 1, 1863, in Oliver Otis Howard Collection, George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections and Archives, Bowdoin College Library; William Tecumseh Sherman to Oliver Otis Howard, December 13, 1863, in Oliver Otis Howard Collection, George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections and Archives, Bowdoin College Library.

3Otis McGraw Howard, Gen. Charles H. Howard: A Short Outline of a Useful Life (Chicago: Privately printed, 1925), 27-31.