Sand, Science, and the Civil War: Sedimentary Geology and Combat by Scott Hippensteel. University of Georgia Press, 2023. Paper, ISBN: 978-0820363530. $44.95.

It is always refreshing to see a novel approach to a topic as endlessly studied as the Civil War, and this is precisely what Scott Hippensteel has delivered in Sand, Science, and the Civil War. Building from his earlier work Rocks and Rifles: The Influence of Geology on Combat and Tactics during the American Civil War, Hippensteel addresses the impact of geological factors on nearly every facet of the conflict. As a geologist and associate professor of earth sciences at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, this is a story Hippensteel is uniquely well-positioned to tell.

As Hippensteel relates throughout the work, geologic processes such as erosion and weathering were responsible for shaping the varied terrain over which Union and Confederate soldiers battled. This includes the creation of well-known landmarks like the Devil’s Den at Gettysburg and the jutting limestone of the Slaughter Pen at Stones River. But geological influences go far beyond rock formations. Streams, rivers, marshes, ravines, and ridges bolstered defensive lines, concealed attacking troops, or rendered areas nearly impassable. The presence of all these features can be explained by geology. Hippensteel notes that a battlefield’s landscape could even alter the effectiveness of artillery fire. While cannonballs could skip across a “gently sloping landscape between gun and target,” the presence of hills or swales would prevent this phenomenon and thereby reduce the lethality of smoothbore cannons (33).

Beyond a battlefield’s topography, geology also governed the creation of fortifications in the field. Hippensteel states that on many battlefields, elevated ground that was otherwise desirable as a defensive position could not “be fortified by digging because of the shallow bedrock” (125). In contrast, Hippensteel argues that the favorable soil near Petersburg and the presence of loess at Vicksburg were significant factors in facilitating the extensive siegeworks and mining operations that characterized those engagements. In addition to the soil’s depth, soil composition determined the difficulties associated with constructing fortifications. Although soldiers could dig in sandy soil with relative ease (as compared to clay soil), the former required more structural support to keep its shape.

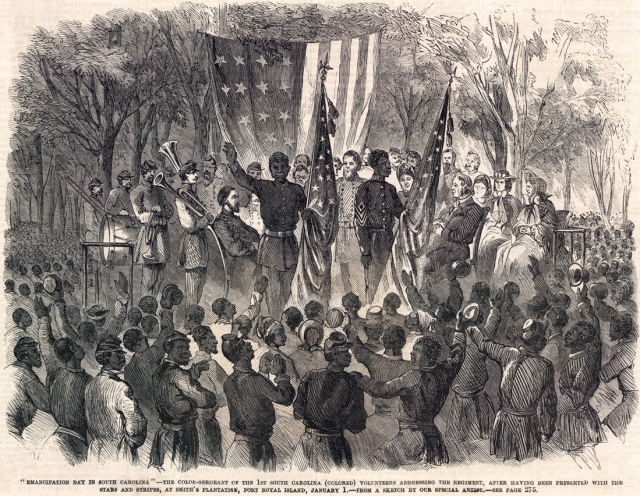

As its title would suggest, sand plays a prominent role in the narrative of Sand, Science, and the Civil War. The Civil War featured the first large-scale use of sandbags, and although the bags themselves wore out much more quickly than their modern counterparts, they still possessed numerous advantages. Fortifications constructed from sandbags took less time to assemble, did not produce debris when struck by enemy fire and, above all, succeeded in protecting occupants from incoming projectiles. Hippensteel asserts that coastal sand fortifications demonstrated “the use of sedimentary geology as a force multiplier,” as Confederate sand-based fortifications like Fort Fisher and Fort Wagner proved able to withstand a tremendous volume of artillery fire without capitulating (233).

Although many geological phenomena were yet largely unknown at the time of the Civil War, Hippensteel shows that some contemporary figures still recognized the relevance of geology to military operations. In the years before the war, West Point professor and military theorist Dennis Hart Mahan investigated the relationship between the materials used in fortifications and their ability to stop projectiles, and Union engineers conducted further testing on this topic on Morris Island in 1863. Yet the figure Hippensteel most emphasizes for having recognized geology’s influences is Union general and engineer Quincy Adams Gillmore. Due to his prominent role in the sieges of Fort Pulaski and Fort Wagner, Gillmore had ample opportunities to study the resistance of brick and sand fortifications to artillery fire. Hippensteel indicates that Gillmore praised the effectiveness of sand to his superiors on multiple occasions.

In addition to incorporating a wide variety of engaging subjects, Hippensteel has succeeded in keeping this work accessible for a general audience. Any necessary geological jargon is clearly defined, and there are plentiful photographs and diagrams to support Hippensteel’s analysis.

When visiting a battlefield, students of the Civil War will inevitably consider the role terrain played in dictating the combat that took place there, but it is unlikely that they pay any attention to the types of soil beneath their feet. In Sand, Science, and the Civil War, Hippensteel makes an excellent case for why they should.

Jeremy Knoll is a graduate student in the Department of History at The Ohio State University.