African American Faces of the Civil War: An Album edited by Ronald S. Coddington. The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012. Cloth, ISBN: 142140625X. $29.95.

When the movie Glory debut in 1989 it was not commonly recognized that African Americans had fought in the Civil War. Although many of the details were fictionalized, the film’s depiction of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry introduced popular audiences to the war’s black troops. Over the last few decades, historians have added to this cultural awareness by increasingly integrating African-American agency into the narrative of the conflict. Books, documentaries, museums, and now even Internet blogs have successfully demonstrated the varied and significant involvement of blacks in the Union war effort.

When the movie Glory debut in 1989 it was not commonly recognized that African Americans had fought in the Civil War. Although many of the details were fictionalized, the film’s depiction of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry introduced popular audiences to the war’s black troops. Over the last few decades, historians have added to this cultural awareness by increasingly integrating African-American agency into the narrative of the conflict. Books, documentaries, museums, and now even Internet blogs have successfully demonstrated the varied and significant involvement of blacks in the Union war effort.

Yet in 2004 Ronald S. Coddington published Faces of the Civil War: An Album of Union Soldiers and their Stories, a collection of 77 photographs that featured no black faces. While the author was at Baltimore’s annual book festival promoting his work, a woman flipped through its pages and then bluntly admonished him. “You know,” she said, “there were men of color who also fought.” That this glaring omission needed to be pointed out is a bit shameful, but it resulted in the author’s determination to correct the oversight. After producing a second book, Faces of the Confederacy: An Album of Southern Soldiers and Their Stories (2008), Coddington began searching for photographs of black soldiers. These proved more difficult to locate than the cartes-de-visites of white soldiers, but his tireless effort has now led to African American Faces of the Civil War: An Album, an impressive collection that in many ways picks up where Glory left off.

The book begins with historian Matthew W. Gallman explaining how the Emancipation Proclamation signified a new relationship between the federal government and African Americans. Just a few years earlier the Supreme Court had ruled that blacks were not citizens. Yet during the Civil War black men were eventually encouraged to fight for the Union, and thus the government recognized their humanity and was reluctantly reopening the question of what citizenship rights, if any, they possessed. Furthermore, when the war ended black veterans and their widows successfully applied for federal pensions, demonstrating that both the applicants and federal officials understood that the government could and should play a role in supporting certain black citizens. Concurrently, Gallman notes, the burgeoning photographic industry had democratized who could record their image for posterity. In American homes photos of celebrities and famous politicians commingled in albums with those of family members and friends. Both black and white soldiers had themselves photographed wearing their uniforms, signifying their pride in serving their country. That African-American soldiers were able to do so, at the same moment when their relationship to their government was in an historic transition, makes Coddington’s collection all the more interesting. As Gallman intriguingly phrases it, the photos were taken “when the sun was setting on slavery” (xlii).

Coddington primarily used the Internet to locate institutions that held photographs of black soldiers. Two-thirds of the images were found in this fashion, revealing (as with most current books) how important online databases and finding aids have become to modern historical research. The author struck particular gold at Yale, finding a photographic collection assembled by a white officer of the 108th USCT Infantry. Coddington also scoured historical societies and various library archives, and used the Internet to connect with genealogical researchers who possessed photos of their ancestors. As with his previous volumes, he sought soldiers for whom short reliable biographies could be constructed. This required accessing military service files, combing through period newspapers (especially African-American-owned publications), and relying heavily on the aforementioned pension applications.

The result is not a scientific sampling of African-American soldiers, yet provides a glimpse at a wide variety of men and their experiences. Here are the stories of runaway slaves, of free blacks from both southern and northern states, and of famous men like Robert Smalls and Lewis Henry Douglass (the son of Frederick Douglass). Some served on the frontlines, others toiled as occupation troops or as prison guards. The reader learns about Nicolas Biddle, possibly the first man wounded in the Civil War, as well as George Mitchell, who served in a regiment that was involved in the war’s last shots. The cast of characters only becomes more interesting from there. William Henry Scott, one of the founding members of the Niagara Movement (the forerunner of the NAACP) is featured. So too is Morris W. Morris, ancestor of famed Hollywood actresses Joan and Constance Bennett. Medal of Honor winners William Carney, Milton Murray Holland and Christian A. Fleetwood are present, yet Coddinton does not shy away from less than honorable stories, detailing, for example, a fight over butter between two soldiers in the 54th Massachusetts that resulted in a fatal shooting.

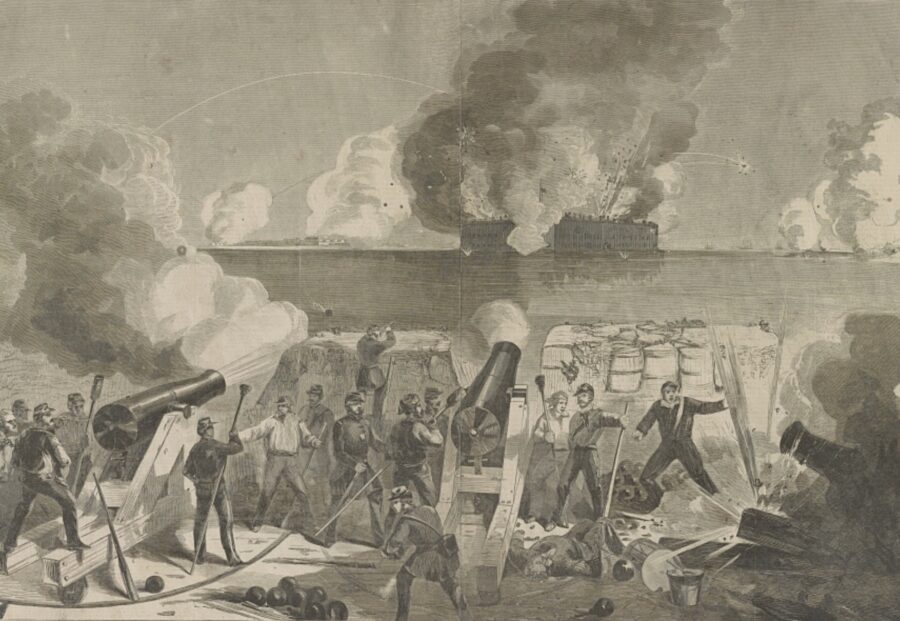

Eleven of Coddington’s 77 subjects served in the 54th Massachusetts, allowing the author to tell the regiment’s story beyond the events depicted in Glory. He provides exciting accounts of the famous attack on Fort Wagner in Charleston Harbor, but also details their heroic stand at Olustee in Florida, and narrates their ultimately successful fight (along with other black troops) for equal pay.

One of the work’s strengths is in providing information about the postwar experiences of the men who survived. Some continued their military service and were sent to the southern border of Texas to intimidate French troops occupying parts of Mexico. Others joined the famed Buffalo Soldier cavalry regiment and patrolled the West. Interestingly, more than a few married women 15-25 years their junior (perhaps the women were inspired by love, but were also no doubt drawn to the financial stability that the veteran’s pensions might provide). Many of the black veterans lived in obscurity, suffering for the rest of their lives with physical and emotional scars. Still others became active in the Republican Party, shaping Reconstruction and becoming community leaders. A few heroically battled Klan organizations or became the “Exodusters” who helped settle the frontier. Historians have recently produced compelling studies focusing on the lives of Civil War veterans, and Coddington’s work will become a valuable source for future such studies.

Indeed, it is as a reference work that the book most succeeds, rather than as the narrative history that it attempts to be. Coddington cleverly organizes the photos and biographies chronologically by dating them according to a significant moment in each subject’s life. This structure is intended to give the book a narrative-drive, but actually only inhibits it readability. A topical approach may have served the author better, allowing the grouping of individual soldiers into themed chapters—one for just the 54th Massachusetts, for example.

Nevertheless, Coddington’s African American Faces of the Civil War is a fascinating work that captures the soldiers at a moment when they proudly served a country that was only just then beginning to reassess their citizenship rights. Because they risked everything to fight for emancipation and the Union, the Civil War’s African-American soldiers deserve to never be forgotten. Coddington’s work will help to ensure that that no one will ever need to be reminded that “there were men of color who . . . fought.”

Glenn David Brasher is a History Instructor at the University of Alabama and author of The Peninsula Campaign & the Necessity of Emancipation; African Americans & the Fight for Freedom (2012).