She Came to Slay: The Life and Times of Harriet Tubman by Erica Armstrong Dunbar. 37 Ink, 2019. ISBN: 978-1982139599. $23.99.

In 2019, Harriet Tubman had a moment. A Hollywood biographical film directed by Kasi Lemmons and starring Cynthia Erivo grossed nearly fifty million dollars and received generally positive reviews. Erivo earned an Oscar nomination for best actress. Millions of Americans were likely exposed to the details of Tubman’s brave life for the first time. Even if the Trump administration has delayed placing Tubman on the $20 bill, her life is perhaps better recognized than ever before.

In 2019, Harriet Tubman had a moment. A Hollywood biographical film directed by Kasi Lemmons and starring Cynthia Erivo grossed nearly fifty million dollars and received generally positive reviews. Erivo earned an Oscar nomination for best actress. Millions of Americans were likely exposed to the details of Tubman’s brave life for the first time. Even if the Trump administration has delayed placing Tubman on the $20 bill, her life is perhaps better recognized than ever before.

Fortunately, Erica Dunbar has made sure that the historical world can capitalize on that popularity with her engaging account of Tubman’s life, She Came to Slay: The Life and Times of Harriet Tubman. Published in the vein of The Notorious RBG, the book is at once irreverent and bold, written in a way that will reach an audience usually turned off by scholarly, dense monographs.

The book is broken into four parts, each divided into multiple subsections that are typically a few pages each. The narrative centers around paragraphs rather than chapters. Dunbar covers Tubman’s early enslaved life in Maryland, with a particular focus on how physical tasks prepared her for her grueling work ahead. (Some of the details covering Tubman’s strength carry a comic book feel.) A large portion of the text, however, is rightly dedicated to Tubman’s extraordinary voyages—thirteen in total—back to Maryland to save her family and emancipate others. In total, Tubman likely freed over sixty individuals in these raids.

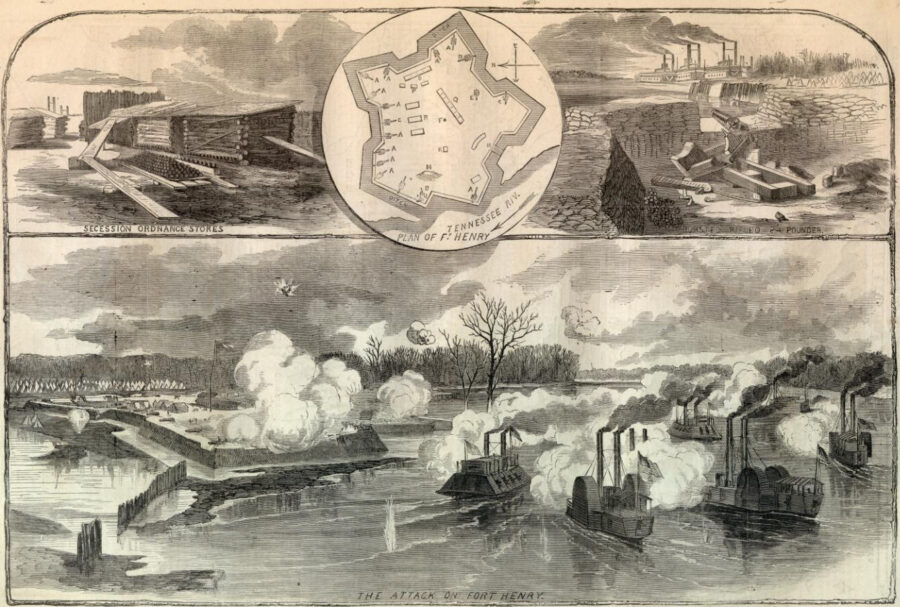

While most young readers likely have a vague awareness of Tubman and the underground railroad, the particulars of this story drive her bravery home. Dunbar pays special attention to the family dynamics at play, centering Tubman’s desire to free her siblings and parents—including her tragic failure to reach one of her sisters in time. Less well-known is Tubman’s work during the Civil War, when she aided troops in South Carolina through both her nursing skills and espionage efforts.

Tubman’s struggles did not end once the war was finished. Though she performed heroic work for the Union cause, she was never paid the salary that she was initially promised, despite frequent appeals for the rest of her life. She also experienced the injustices that were common to Black Americans and dealt with the pains of poverty. Even her memoir didn’t bring as much success as anticipated: because she remained illiterate, she relied on a white author, Sarah Bradford, and the resulting book underwhelmed. These pitfalls did not lessen her energy, however, as she continued to press for reform, including on the issue of suffrage, which dominated her final years.

Dunbar centers two themes that drove Tubman’s actions: her courage and her faith. The latter is especially noteworthy, as it is often easy to glance over the religious fervor and providentialist mindset of abolitionists. But She Came to Slay does not underemphasize the role that Tubman’s religiosity played, including when her visions—often tethered to episodes of epilepsy—made her collaborators uncomfortable.

Dunbar’s tone reflects popular culture. The useful genealogy chart that traces her siblings and nieces and nephews is titled “Harriet’s Fam” (10-11), and the outline of her closest associates, “Harriet’s Homies” (73). Throughout, this playful rhetoric simultaneously highlights the cinematic quality of Tubman’s life and helps to reach a younger audience more comfortable with social media discourse than historiographical interventions. The book aims—and succeeds—at making Tubman a relatable role model.

The design qualities of the book are striking. The colorful artwork is both appropriate and gorgeous. Indeed, given the text’s tenor, sometimes I felt that the work could have relied as much on illustrations as text. Some of the paragraphs ran a touch long given the book’s overall feel, though it can certainly be difficult to limit details when they are so numerous and memorable. Containing Tubman’s narrative is no easy task.

In an era where humanists in general, and historians in particular, are encouraged to reaffirm their significance and add their voices to public discourse, She Came to Slay is a model of how to write an engaging text for a younger, general audience. Perhaps the best compliment I can give is that my eleven-year-old daughter enjoyed it as much as I did. Along with the young reader’s edition of Never Caught, Dunbar is making sure that America’s rising generation is aware of its brave but sometimes overlooked ancestors.

Benjamin E. Park is Assistant Professor of History at Sam Houston State University. His most recent book is Kingdom of Nauvoo: The Rise and Fall of a Religious Empire on the American Frontier (2020).