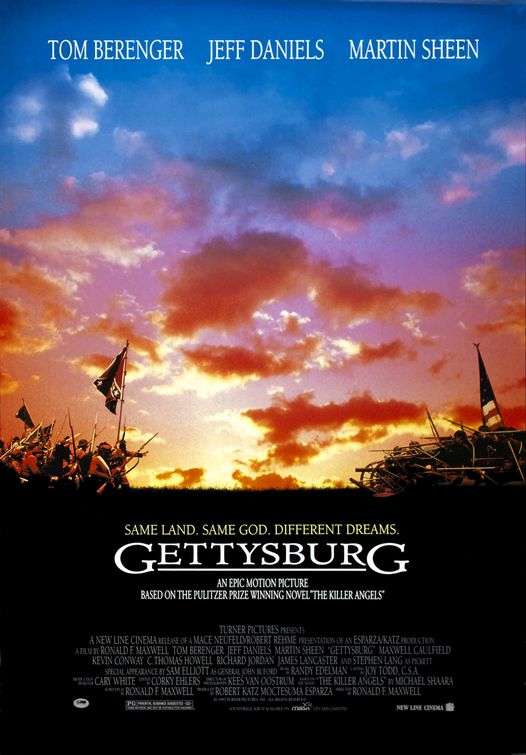

As a special “thank you” to our eNews subscribers, we offer you this first look at our Q&A with Ron Maxwell, director of Gettysburg. Here, Maxwell tells how Gettysburg almost didn’t get made and why he thinks the film is so enduring.

Q&A with Gettysburg director Ron Maxwell

In June 1863, it took the Army of Northern Virginia and the Army of the Potomac 28 days to move from their camps at Fredericksburg, Virginia, to the fields and hills around Gettysburg. For filmmaker Ron Maxwell, bringing their story to the big screen took 13 years of struggle, culminating in triumph with the 1993 theatrical release of a movie that helped launch a great Civil War reawakening. Here, Maxwell tells how Gettysburg almost didn’t get made—and why he thinks the film is so enduring.

Where did the idea for the movie come from?

My second wife read The Killer Angels and said to me, “I think you could make this into a movie.” This was in 1978. I read it on a train to Los Angeles. As soon as I arrived I called my agent and said, “I have to make this movie.” It was a great piece of literature with incredible characters that took an impossible thing—the Battle of Gettysburg—and made it conceivable. I was absolutely swept away. A few years later—after I’d acquired the rights to the book but before I had started the screenplay—I spoke with author Michael Shaara. He offered to walk me through the battle. So we met in Gettysburg—it was my first trip there—and Michael was my guide. We walked the battlefield the way his novel breaks it down. It was an experience I’ll never forget.

What was the first reading of the screenplay like?

My good friend Richard Jordan—the actor who played Confederate general Lewis Armistead in the movie—helped me organize a reading. A few dozen top-notch actors agreed to read parts: Blair Brown was Fanny Chamberlain, Hal Holbrook read Robert E. Lee, and Peter Donat read James Longstreet. We started around 6 p.m. and finished about midnight. When we got to the last page, the room fell silent. Some of the actors had tears in their eyes. And then they just spontaneously applauded. They weren’t clapping for me. I knew in that moment I was going to make the movie, no matter what.

But you ran into challenges?

Plenty. Early on, Hal Holbrook connected me with Ted Turner, who loves the Civil War. But TBS, his cable channel, didn’t have the budget. So I looked for other ways to get it produced. I went to Poland and Hungary, where all those big Napoleonic movies were made and where you could rent an army. At the time, reenacting was really growing in the U.S., so the option of making the movie stateside was looking more desirable, because instead of mere extras I’d have thousands of Civil War buffs filling the screen. But nobody in Hollywood seemed interested in an epic about the subject.

What changed?

When my friend Ken Burns’ documentary The Civil War aired on PBS in 1990, the network executives were shocked that some 40 million people tuned in. Within a week, CBS announced it was doing a big miniseries on the Battle of Gettysburg. I couldn’t believe it. I’d been at work on this movie for over a decade, with hardly a bite. And now somebody else was going to do Gettysburg. I knew CBS wouldn’t be able to commission a script overnight, especially one like we had. Still, we had to scramble. We pitched NBC and ABC, capitalizing on the herd mentality in Hollywood. We made a deal with ABC, but then they dropped us. Suddenly we were back in the dumpster.

Then, Ken Burns got a Producers Guild Award for The Civil War. He told me to come, because Ted Turner would be presenting his award. During the presentation, Ted spent 15 minutes talking about how nuts it is that Hollywood doesn’t want to produce Civil War films. Later, he asked me the status of my movie. I told him. He said, “Let’s do it—have your people call my people.” Within 48 hours we had a handshake deal.

And the rest is history.

Not quite. A Turner development executive with no connection to the material called for a total rewrite of the screenplay. The new version was terrible—but luckily that executive got fired. Who came in to replace her? The ABC executive who had made a deal with us a few years earlier. Within 48 hours he greenlit the original script.

Gettysburg was supposed to be a TV miniseries. It’s why we filmed five hours of material. But when Ted Turner saw the first week’s dailies, everything looked so good, especially the acting, so he decided he’d release it theatrically, as a long film with an intermission. Fortunately, we were filming in theatrical format, not the squarer format associated with television production, so the switch was seamless.

Do any particular moments or scenes stand out for you?

Two come to mind. The first scene we filmed, with Robert E. Lee and James Longstreet before the first day’s battle, as they pass by a brass band playing “Bonnie Blue Flag,” and the last scene we filmed, when the Chamberlain brothers embrace at dusk, after the battle is over. Also, I was amazed by the commitment the actors brought to their roles. When Stephen Lang heard we were casting the movie, he walked up to me backstage at a play in New York and introduced himself by saying, “Hello, I’m George Pickett.” All of the actors had the same attitude. They were so happy to be part of the production, and lost themselves in their characters. Just total immersion.

Do you think Gettysburg has stood the test of time?

In April 2012, the Smithsonian held a Civil War weekend where they screened four movies: Gone With The Wind, Glory, Gettysburg, and its prequel, Gods and Generals. People came up to me to shake my hand and thank me for both Gettysburg and Gods and Generals. Both films continue to be watched and have been embraced by American and international audiences. It all comes back to the story. At its core, Gettysburg is a movie about officers in high command. Why do good, moral, ethical people go to war? The exploration of why they were fighting—I think we got that right.