William Tecumseh Sherman, In the Service of My Country: A Life by James Lee McDonough. W. W. Norton, 2016. Cloth, ISBN: 978-0-393-24157-0. $39.95.

Can anything new be written of William Tecumseh Sherman? Commonly regarded as the second-greatest soldier to fight for the Federal armies in the War of the Rebellion, and one of the most influential general officers to shape the U.S. Army in the era of Reconstruction, William Sherman has inspired numerous biographies through the years. These include Sir Basil Henry Liddell Hart’s iconic Sherman: Soldier, Realist, American [1929], John F. Marszalek’s incisive Sherman: A Soldier’s Passion for Order [1993], and Michael Fellman’s Citizen Sherman: A Life of William Tecumseh Sherman [1995], perhaps the most critical of Sherman appraisals. More than twenty-five years later, popular interest in Sherman shows no sign of abating. Since its publication in 2016, James Lee McDonough’s William Tecumseh Sherman, In the Service of My Country: A Life has already been eclipsed as the latest installment in the Sherman literature with the publication of Brian Holden Reid’s much-anticipated biography, which arrived on bookshelves earlier this year.

Can anything new be written of William Tecumseh Sherman? Commonly regarded as the second-greatest soldier to fight for the Federal armies in the War of the Rebellion, and one of the most influential general officers to shape the U.S. Army in the era of Reconstruction, William Sherman has inspired numerous biographies through the years. These include Sir Basil Henry Liddell Hart’s iconic Sherman: Soldier, Realist, American [1929], John F. Marszalek’s incisive Sherman: A Soldier’s Passion for Order [1993], and Michael Fellman’s Citizen Sherman: A Life of William Tecumseh Sherman [1995], perhaps the most critical of Sherman appraisals. More than twenty-five years later, popular interest in Sherman shows no sign of abating. Since its publication in 2016, James Lee McDonough’s William Tecumseh Sherman, In the Service of My Country: A Life has already been eclipsed as the latest installment in the Sherman literature with the publication of Brian Holden Reid’s much-anticipated biography, which arrived on bookshelves earlier this year.

But McDonough’s opus merits careful reading on its own terms. With eloquence and verve, the author chronicles Sherman’s childhood, the young Tecumseh’s military service in the antebellum era, his rise to martial glory in the American Civil War, and his postwar service as Commanding General of the U.S. Army. Along the way, McDonough identifies the United States Military Academy as essential to “Cump” Sherman’s intellectual, physical, and social formation. He captures Sherman’s fondness for Florida, as well as his enthusiasm for southern high society in Mobile and Charleston. Sherman was a socialite, and those who remember the general for the “destructive war” he is said to have inaugurated in American armed conflict may be surprised to learn that the red-headed soldier loved dancing, parties, painting, and the theater. Sherman was a humane soldier, a man deeply self-conscious of his professional failings, one who longed for the elusive comforts of domestic life, one who doubted that he would survive the Civil War, and one who was utterly devastated by the sudden death of his firstborn son. From his youth, Sherman held partisan politics in contempt, and in retirement refused to seek the office of President of the United States even as one of the most popular figures in American public life. To the end, he believed that politics were dishonorable to a soldier (706).

Sherman was eccentric, and throughout McDonough’s narrative, the general and his contemporaries sometimes appear in humorous lights. While in command of occupied Memphis, for example, Sherman attended religious services at Calvary Episcopal Church. One Sunday, when a clergyman failed to invoke a blessing upon the President of the United States, Sherman—who was not particularly religious, but admired President Lincoln and knew instinctively that the minister had excluded the presidential blessing—rose and forcefully recited the prayer on behalf of the president for all to hear. Sherman later threatened to close the parish if the slight against Lincoln were repeated (336).

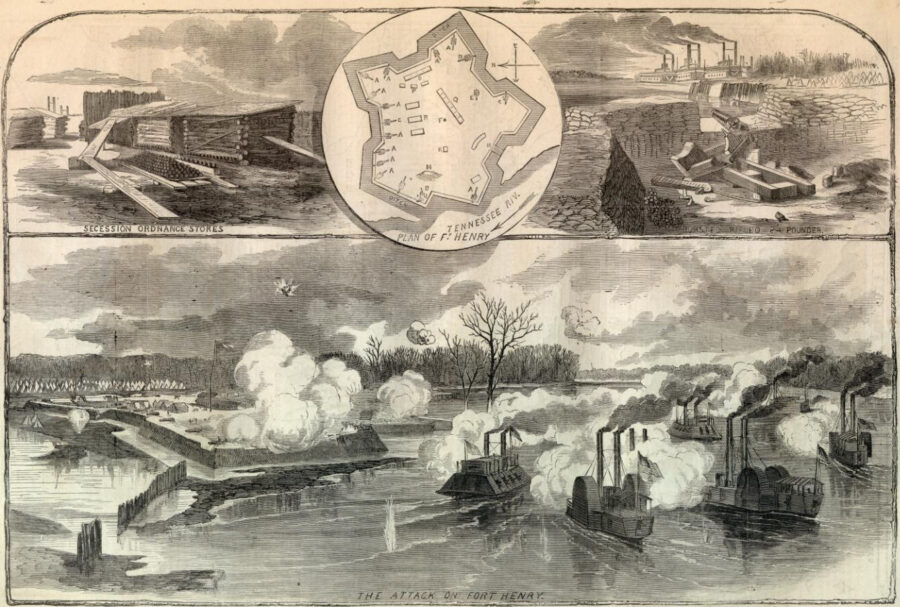

At 832 pages, In the Service of My Country is a hefty tome, though the narrative is generally balanced. Military affairs predominate. An accomplished military historian of the war, McDonough hits an easy stride describing battles and operations in which Sherman was instrumental. Though it is common for scholars to fixate on Sherman’s military actions in 1864, McDonough stresses the centrality of the Battle of Shiloh (in 1862) to Sherman’s army career. “Shiloh marked the irreversible resurgence of Sherman as a soldier,” the author contends (19). Significantly, the victory in Tennessee put to rest false claims of Sherman’s ineptitude and madness that had haunted the general in Kentucky and driven him nearly to despair. McDonough devotes the space one would expect to Sherman’s more memorable Atlanta and Savannah campaigns (chapters 22 and 23). Throughout, the author captures Sherman’s logistical grasp and his masterful sense of military supply. In the main, McDonough sought to analyze Sherman’s generalship, and in this he has largely succeeded (xi).

Nevertheless, in a book of this size, there are missed opportunities. The author underscores Sherman’s complicated marriage throughout, which was loving and fruitful but also marked with frustration, especially on account of Ellen Ewing Sherman’s Roman Catholicism (which William did not share), Ellen’s deference to her parents even after her marriage to Sherman, and her distaste for social engagements. In the end, however, he equivocates on the question of Sherman’s supposed marital infidelity (689, 706). Sherman’s understanding of politics was almost classical in its orientation. Sherman, for instance, like Roman republicans of old, viewed political society as belonging not only to the living but also to the many millions of citizens yet unborn, and believed that a constitutional government erected upon a foundation of ordered liberty, with a strong army to sustain that government, was a “blessing” for posterity (452). Yet McDonough does not probe Sherman’s politics in this sense. Nor does he examine Sherman’s sense of justice—which was essential to the general’s understanding of state-sanctioned violence, and imbued his use of force with a great moral imperative—as have other scholars.

Analysis of Sherman’s tenure as Commanding General of the U.S. Army from 1869 to 1883 is uneven. McDonough notes post-war feuds, and chronicles how Sherman’s relationship with President Ulysses S. Grant cooled as general in chief (666-7). The author allocates more space to Sherman’s grand European and Mediterranean tour than to military reforms, and the general’s establishment of the Infantry and Cavalry School of Application at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, receives only passing treatment (687). Indeed, Sherman’s distinction—in historian Russell F. Weigley’s memorable telling—as the “principal founder of the army’s postgraduate education system” would seem to merit more coverage in this work than it receives.[1]

Curiously, too, the author devotes only several pages to Sherman’s Memoirs (708-711). This is disappointing, given the significance of Sherman’s textfor the genre (Weigley has likened Sherman’s Memoirs to a military textbook, and noted their uniqueness among all contemporaneous reflections on war in this respect).[2]

The author strives to maintain critical separation from his subject. He confesses a certain admiration for Sherman even as he expresses revulsion at some of the general’s moral failings (xii). Yet Sherman appears in favorable lights throughout. Several of the chapter headings in this study—“Deprived of Military Glory,” “No Man Can Foresee the End,” “This is No Common War,” and “We Can Only Bow to the Inevitable” (taken from Sherman’s writings)—imbue the narrative with an exceptional and almost mythic quality. Cynical readers may take issue with such a favorable impression of Sherman. Many Americans in the twenty-first century are skeptical of heroes and of military greatness. Readers may wonder, for instance, with Sherman’s racialized views of Native American Indian tribespeople in the West, why McDonough does not scrutinize his subject with greater rigor.

McDonough has provided students of history with a capable—and often moving—biography of a worthy subject. Those with interest in the life and times of William Tecumseh Sherman will enjoy the author’s colorful narrative. In its use of Sherman’s extensive correspondence, the general’s Memoirs, and relevant secondary sources, In the Service of My Country is factually sound (this reviewer noticed only one error in the notes section: a prominent secondary work was incorrectly titled). McDonough’s is the lengthiest of Sherman biographies in print today, and because of the excellent craftsmanship at W. W. Norton, one of the most handsomely produced. One does wonder, in the final analysis, whether In the Service of My Country offers greater clarity in its insights, or more originality in its conclusions, than some of the more-established alternatives in this crowded literature. But the bottom line is that McDonough’s life of General Sherman is a pleasant book to read, and a suitable choice for those who desire an accessible and reliable study of a great American soldier.

Mitchell G. Klingenberg, Ph.D., is a historian in the Department of Military Strategy, Planning, and Operations at the U.S. Army War College. His writings have appeared at War on the Rocks, War Room, Civil War History, and American Nineteenth Century History. He is at work on a military biography of U.S. Major General of Volunteers John Fulton Reynolds.

[1]Russell F. Weigley, Towards an American Army: Military Thought from Washington to Marshall(New York: Columbia University Press, 1962), 82.

[2]Weigley, Towards an American Army, 83.